© Always Worth Saying 2022, Going Postal

Over breakfast on the morning of Friday, August 15th 1952, readers of the letters page of the Ilfracombe Chronicle and North Devon News may have noticed the following correspondence from a Mr Cuthbert Burgoyne of Yew Tree Cottage, Brook, near Godalming.

Sir, recently I have been staying for several weeks in Lynmouth, a beauty spot that has beaconed me back many times during the last 30 years. With your permission, I would like to compliment the local council on the admirable way in which they have succeeded in meeting the needs of their countless visitors during the season.

Mr Burgoyne also complimented the aldermen on their unobtrusive promenade and excellent putting greens while noting ‘the builders’ had been successfully thwarted regarding nefarious plans for the Manor House grounds. A cloud on the horizon was the possibility of charming Lynmouth and neighbouring Lynton being spoilt by uncontrolled commercialism with the attendant hazards of trailer caravans, motor coaches and traffic. As the good people of Lynmouth, local and visitor alike, turned the page to address the WI news over their Full English, a darker cloud approached with the first ominous spits of rain forming a mosaic on spotless boarding house bay windows. In the background, a Exmoor already heavily sodden by previous days of summer showers glowered menacingly over their township.

Half a decade before the launch of Sputnik promised that such things would be done by satellite photography, weather ships out at sea took their readings and radioed them to England. On that Friday, they told of an area of low pressure vacuuming moisture from a warm summer Atlantic and bellowing a stormy front eastwards towards Devon and Cornwall. According to the Meteorological Office in London, the highest temperature that day, 23.9C, then as now was recorded at an airfield, Mildenhall in Suffolk. The lowest, then as now, was at Eskdalemuir in Dumfrieshire where the mercury crept down to 6.1C. Three hundred miles south, the Met Office’s subsequent summary of the following day in the west of England was to read as follows,

Continuous rain began on the Isles of Scilly and at Culdrose (Cornwall) during the early hours and spread to all parts of Devon, Cornwall and Somerset by midday. At Chivenor (Devon), the nearest synoptic reporting station to Lynmouth, and at St. Eval, in north Cornwall, the rain was almost incessant for 18 hours or more.

At Longstone Barrow on Exmoor, 9 inches of rain were recorded in 24 hours from 0900 GMT on 15 August. The highest rate of rainfall was estimated to be more than an inch per hour, which occurred between 2030 GMT and 2230 GMT on the 15th. Other high rainfall values: Challacombe, 7.58 inches, Simonsbath, 7.35 inches. By Friday night floods were sweeping through the holiday county of North Devon.

The first victims of the torrent were Manchester Boy Scouts from a Moss Side troop camped next to the River Bray at Filleigh near South Moulton. Harold Shaw, 14, and Derek Breedy and Jeffery Robinson, both 11, perished as their tents were washed away. Rescuers working by searchlight and flares discovered two of their bodies during the night. Also during the night, 61-year-old William Leathworty was found dead three-quarters a mile from his home in the village of Parracombe four miles from Lynton. It is thought he had been swept away after going to his front door.

Ominously, Mr Leathworthy was discovered surrounded by concrete posts, trees and roofing iron as the deluge took wreckage down the hillsides. Such debris was to amass behind bridges and ‘pond’ water until the resulting build-up of pressure swept the bridges away and hammered the next part of the valley with a surge in water. Lynton and Lynmouth became cut off by collapsed river crossings, by inundated roads and by fallen telephone wires. The towns were left without sewage, water and lighting. Initial reports told of a raging torrent that damaged a hotel, a garage and carried away a number of cars.

© Always Worth Saying 2022, Going Postal

At sunrise the situation appeared much worse. The police reported a state of chaos and requested the BBC broadcast a warning that “only persons with genuine business will be permitted to approach either Lynton or Lynmouth”. Large trees and parts of demolished buildings had been carried down the west and east tributaries of the River Lyn, piled against the bridges in central Lynmouth and had collapsed them. The river Lyn, which had been culverted through the town for many years, had not only broken free but had carved itself new courses to the sea.

While troops joined police and firemen to erect an emergency bridge, news began to emerge of the previous night’s fear and heroism. An elderly invalid, Mrs Summers, was afloat in her bed and was only rescued in the nick of time. Mr and Mrs Gowling and their 19-year-old son Donald had to retreat through a hole made on the roof of their cottage after a side of a house collapsed. In the raging torrent, firemen came down the cliff behind the Bath Hotel, attached a rope across a street and hauled people out of windows to safety.

By Sunday there was still five feet of water in Lynmouth’s main street. The Sunday People reported the change in the course of the River Lyn had split Lynmouth into three with the foot of Lynmouth Hill having become a yawning chasm, 75 ft wide and 20ft deep. Residents had been evacuated to Minehead where the army and police provided them with hot tea and food.

Two hundred men set to work at once to restore the river to its original course. Flood levels were slightly down but water still raced through the streets. Police expressed concern at the number of missing people but hoped many were holidaymakers who had left the area on account of the weather and flooding.

A jumpy population were wary of further catastrophe. Half the people of Challacombe fled their homes in terror upon a false rumour that the 15 million gallon reservoir above their hamlet had burst.

Back in Lynmouth the following Tuesday, the Minister of Housing and Local Government, Mr Harold Macmillan, visited the scene. Upon his arrival and in continuing rain and light drizzle, the body of a woman who had been found amongst debris on the foreshore moments earlier was carried past him on a stretcher. Another body was found at the same spot before the future Prime Minister left. In between times, a wet and muddied Mr Macmillan clambered over the remains of a local hotel and shouted to survivors over the noise of pneumatic drills, bulldozers and blasting as workmen toiled to reclaim the old river channel.

In the harsh light of the following days it emerged that one hundred buildings had been destroyed or seriously damaged. Twenty-eight of thirty-one nearby bridges had been downed. Thirty-eight cars were washed out to sea. Four hundred and twenty people had been made homeless. Accross the county thirty-four had lost their lives.

The country rallied round. Devon Women’s Voluntary Service fitted out hundreds of evacuees with clothing brought by the truckload after being donated from different parts of Britain. Within weeks, Lynton’s town appeal had reached an impressive £13,000. In generosity repeated the length and breadth of the land, hundreds of miles away in Sussex, Worthonians raised £1,500 from over 700 donations, one of £100, at a time when a working man might earn £3 a week.

Although it might seem mawkish and unhelpful to visit the area and take photographs, the people of North Devon understood the usefulness of tourism. A Mrs Bohn of the Green House Cafe, Lynton, telegrammed the Queen at Balmoral saying:

“Lynton traders desperate. I respectfully ask Your Majesty to advise the Lord Lieutenant of Devon to lift the ban on tourists to Lynton at once.”

In response, the Chief Constable of Devon, Lieutenant-Colonel R Bacon, announced travel restrictions would remain in place while military necessities took priority. Heavy vehicles on the road made it unsafe for civilian traffic. The Ministry of Labour assured concerned locals that employers would relocate staff elsewhere and many hands would be needed for re-building work in the town.

The existence of the family photographs below, and their capture of a motor coach and women in summer dresses, suggests that, as ever, the tea room proprietor was more in touch with the public mood than the Lieutenant-Colonel.

© Always Worth Saying 2022, Going Postal

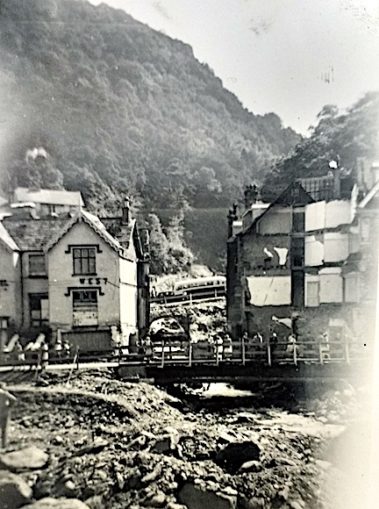

The picture above picture shows the devastated lower floor and boarded upper windows of the Lyn Valley Hotel. Presumably the masonry to the bottom left is what remains of the top of the West Lyn culvert. The emergency wooden bridge can be seen to the right, with a wasteland beyond dotted with a few surviving trees leading towards the seafront.

The picture below shows the damage to the front of the Lyn Valley Hotel with part of the four-story hostelty having been torn away. The temporary bridge can be seen again and in the background another bridge that has fared better and only requires wooden handrails where parapets once stood. The building to the left was also a hotel, the West Lyn. It’s lower story was the West Lyn Cafe which is burried about half way to ground floor ceiling level in rubble.

© Always Worth Saying 2022, Going Postal

This part of the town was rebuilt after the flooding in a much-altered state. With both the Lyn Valley and West Lyn being demolished, a wide, concrete-lined river channel was excavated a distance from the remaining buildings and new, wider and longer bridges were constructed.

It is possible to stand on the same spot and have a look around via Street View but a degree of imagination must be employed to recreate the scene of seven decades ago. About the site of the Lyn Valley Hotel sits The Lynn Valley Guest House. What was the West Lynn Hotel is now excavated river bed. A new thoroughfare down to the seafront is called Riverside Road with the original route, Lynmouth Street, still tucked before the hillside and still hosting the Bath Hotel.

Further down Riverside Road and opposite the harbour sits Lynmouth Flood Memorial Hall on the site of the former lifeboat station which was destroyed in the flooding. A relaxed ten-minute stroll inland brings the visitor to Middleham Gardens, laid on the site of the hamlet of Middleham which was obliterated in its entirety during the tropical deluge. Maintained by volunteers, the hidden gardens provide an appropriate and peaceful vantage point over the trickling East Lyn at which to ponder the tragic events of seven decades ago and recall the thirty-four unfortunate souls who were lost.

Middleham memorial gardens, Lynmouth,

Ruth Sharville – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

© Always Worth Saying 2022