Watching formal schooling, community spirit and childhood and family life in general being relentlessly trashed in recent years has made me think more and more about my growing-up years in a small Leicestershire village between the mid-1950s and the mid-1960s. And be very grateful.

In short, it was idyllic.

Thinking back over it all now it makes me realise that the whole time was a rich learning experience that shaped the 4-year old boy that I was into the 14-year old lad that I became (and, ultimately, the 70-year old pensioner that I am now).

It therefore seems appropriate to view my experiences, loosely, in the form of a school timetable.

Geography

The village of Barkby lies about five miles from Leicester and two miles from the nearest town of Syston. It is an old village – it was mentioned in the Domesday Book and, at least until the time I left, had changed very little since.

Barkby, near Leicester. St Mary’s Church and the Malt Shovel on Main Street, Barkby,

Kate Jewell – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

It had a population of about 450, almost exclusively agricultural workers, and was served by a church, two pubs, two shops, a blacksmith, a rose nursery and a genuine village squire – all but the two shops are still there.

The main industry was a mix of cattle and arable farming which was shared out among fifteen farms in the village itself and the outlying hamlets. These fifteen farms were owned by three generations of five families.

Ownership of each farm progressed through the generations – when Old Mr Smith died, his farm would be taken over by Mr Smith, who would then become known as Old Mr Smith, and his farm would be passed on to his oldest son, who from then on would become known as Mr Smith and be replaced in his farm by his oldest son, who then became Young Mr Smith (obviously they weren’t really all called Smith, I am merely preserving anonymity!)

I don’t know if this still happens today but it seems to me that it was a very satisfactory way of introducing fresh blood and new ideas into each farm without losing family ownership and one which had worked very well over the years.

History

As I mentioned, Barkby is described in the Domesday Book and had (and still has to this day) a hereditary squire dating back almost to that time. In my time he was a very powerful individual as he owned everything in the village – even the large farms were merely rented from the squire. Fortunately he was a proper gentleman and could frequently be seen walking through the village with his gun-dogs, being greeted by his tenants and we kids alike with a “Good morning, Sir” and responding to each adult by name and to the kids with a smile.

He lived in a large hall in the middle of the village surrounded by his country estate. Apart from being a landlord, his duties included regularly visiting the school to test the kids and give them uplifting talks (usually involving people like Lord Baden-Powell and Albert Schweitzer), and maintaining the official meteorological records for the village.

As it happened, I briefly had an interest in keeping weather records and when he found this out he invited me and a friend up to the hall to see what it entailed. We were instructed to, at the appointed time, go up the path to the kitchen door at the back, knock and introduce ourselves to Cook who would take us through to him in the billiards room where he kept the records (I swear I’m not making this up).

He must have devoted a couple of hours to us (including rustling up a cup of tea from Cook) and I have never forgotten his kindness.

A less enjoyable encounter was the time I was caught by the village policeman cutting off a couple of branches from a holy bush on the squire’s estate to give to my teacher for Christmas decorations.

He marched me up the path, knocked briskly on the door and loudly and, in hindsight a touch melodramatically, asked Cook to tell the squire what I had done. With equal gravity, she said she would make sure he knew of this heinous act but that if I told her I was sorry she was sure he’d overlook it. I mumbled an apology and was told to ‘oppit by the policeman, which I did at full speed, lesson learned!

Assembly

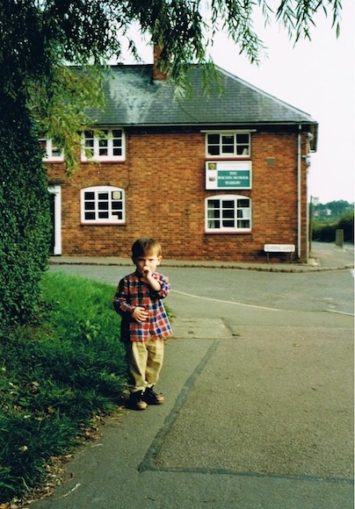

The school had about 45 pupils in total, split between infants, ages 4 to 9, and juniors, ages 9 to 11. The junior’s class was run by the headmistress, Miss Cutts, and infants by her deputy, Mrs Price. There were no teaching assistants.

© Jerry F, Going Postal 2021

Once a week both classes would get together for assembly at which Miss Cutts would tell us stories, usually from the Bible, and we would sing a hymn or two while Mrs Price led us on the piano. The hymns I remember most fondly are ‘New Every Morning is The Love’, ‘To Be A Pilgrim’ and ‘All Things Bright and Beautiful’. From time to time the vicar would call in to give us all a slightly longer extract from the Bible, delivered in rather more stentorian tones than those of the mild Miss Cutts.

Music

Mention of the hymns at the weekly assembly reminds me of my other main brush with song in my time at school. Each year we had a Christmas carol concert to which the squire, the vicar and our parents were invited to marvel at our prowess. And each year the boys had first to undergo an audition with Mrs Price to determine whether or not our voices were beginning to break.

Depending on the results of this audition, we would either take centre stage and put Aled Jones in the shade (were it not for the fact that it was long before his time) or, as in my case, be instructed to stand in the back row and open and shut our mouths in time to the music without making a sound. Looking back, I think she must have thought we were rather older than we were. Or she was tactfully weeding out those of us that just couldn’t sing!

Music was involved in my only other artistic memory although, to this day, I don’t know who was responsible for it. In the early 1960s, as the Beatles were preparing to launch themselves on Hamburg, and Britain heartily embraced rock’n’roll, someone in authority decided that what the school really needed was a Maypole.

Quite why was never explained but, for a couple of years, Wednesday afternoons were reserved for skipping lethargically around the Maypole to the accompaniment of an equally lethargically played by accordion. I have no further recollection of the sessions, but I suspect that I was not very good at them.

Biology

I spent much of my time outside of school on a farm with my best friend, the son of one of the current Young Mr Smiths, who was destined, you will recall, to become Mr Smith, leaving my friend, in time, to become Young Mr Smith.

We spent our days blissfully playing in haystacks, scrumping apples and generally doing the things that country boys had done for centuries, and some more modern things like being driven by Mr Smith the three miles to one of the other farms in the boot of his 1955 Humber Super Snipe Limousine. Well, it seemed like a good idea at the time.

The farm was a dairy farm and was possessed of a particularly fine cow who had already contributed several first class specimens to my friend’s father’s herd, although at that time I was blissfully unaware of quite how she had achieved this.

All that changed one day when a bull had been engaged to service her and Mr Smith omitted to make sure that we lads were well away from the yard when the head stockman brought the bull in to introduce him to the cow.

She was promptly rammed against the stable door as the bull forcefully made her acquaintance from behind, taking the barn door off its hinges in the process. The look in that poor cow’s wide eyes has stayed with me to this day.

Once the process was concluded, Mr Smith, in a matter-of-fact sort of way, asked the head stockman, “How do you think he bulled her, Jack?” to which he got the mundane reply, “Very well Boss”. All very business-like. I was left shocked, but I like to think that it left me with a determination to handle my own trysts in a rather more sensitive way when the time came.

Physical Education

We had no formal physical education, but once a year the whole school, parents and important people from the village got together for Sports Day. This was held on the cricket ground opposite the school and consisted of the usual events including the sack race, the three-legged race and, best of all, the egg and spoon race.

© Jerry F, Going Postal 2021

With a total of 45 kids, both boys and girls, between the age of four and eleven there was never going to be a particularly fair competition but, as it said on the certificates the victors were awarded, “The important thing is not the winning but the taking part.” As a consistent non-winner, the profundity of that was lost on me.

© Jerry F, Going Postal 2021

After the formality of the prize-giving ceremony, with trophies and certificates given out by a village worthy, the highlight of the day began. This was a slap-up tea in the cricket pavilion followed by a screening of a selection of Charlie Chaplin, Laurel and Hardy and Buster Keaton 8mm films.

A wonderful day was had by all.

Playtime

Playtime always began with a third of a pint of either warm or frozen milk, depending on the season, and was followed by fifteen minutes of running round like maniacs, a game of the rather more formal British Bulldogs, or the definitely-not-at- all-formal “seeing who can wee highest up the wall of the outside toilet (boys only)”.

Dinnertime

Dinner was served by a bunch of dinner ladies who I swear had seen active service on the Eastern Front. They certainly took no prisoners.

The meals themselves were, I imagine, the same as school dinners everywhere – a nondescript and suspiciously gristly meat course followed by a surprisingly good variety of puddings – jam tart with custard, semolina or rice pudding with rosehip syrup, queen of puddings (served with a lump of cheese for reasons I never found out) and, my personal favourite, chocolate blancmange with cornflakes.

Where the problems began with the dinner ladies was when you didn’t like a particular offering. This happened to me with most main courses (I date my loathing of liver in particular to this time). When this happened they were not above employing strong-arm tactics to “persuade” you to eat up.

My worst experience of this was with prunes, a particularly vile fruit in my opinion. The dinner ladies were not open to my plea that I didn’t like prunes and were adamant that I was going to eat them. To ensure this, one of them grabbed the top of my head with one hand and my lower jaw with the other to force my mouth open while another one rammed a spoonful in and they both then held my mouth shut until I swallowed. A thoroughly unpleasant experience that somehow I don’t think would be allowed today.

I have blanked out the rest of the memory, but I suspect that the prunes may have made a prompt reappearance. Unsurprisingly, I have never allowed myself to even be in the same room as a prune to this day.

Home Economics

Our cottage was built in 1873 as a pair of detached farm labourer’s dwellings and hadn’t been improved since. As a result, we had neither electricity nor water.

© Jerry F, Going Postal 2021

Ours was the left-hand side of the semi-detached cottage. The stains where the water butt and drainpipe were can be seen on the side wall. To the rear is the washroom, with the dreaded toilet shed behind that.

Without electricity, evenings were spent around the cast iron range in the kitchen reading, playing card games or most often listening to a radio powered by lead-acid accumulators. These were what seemed to be blocks of thick glass containing acid and were very heavy. They had to be recharged (at a chemists, I think) every few days and when that was necessary, my dad would set off on his bike on the five-mile journey to Leicester with one on either side of his handlebars.

This must have upset the stability of his bike and, as might have been expected, one day he came off, shattering both newly-recharged accumulators and spilling the acid all over himself. He was not amused at our laughter when he returned home and stood in the doorway with wisps of smoke coming from the holes in his demob issue raincoat, looking like an extra from a Boris Karloff horror movie.

When the allure of the BBC Home Service waned (and believe me it did, often) my dad would get out the old wind-up gramophone and his collection of 78s from the 1930s, 40s and 50s and we would have a musical evening. My favourites included ‘Tiger Rag’ by Harry Roy’s Tiger Ragamuffins and ‘Clink, Clink, Another Drink’ by Spike Jones and his City Slickers, my copies of which have sadly long since suffered the fate of most 78s over the years.

© Jerry F, Going Postal 2021

Another consequence of not having electricity was that all cooking had to be done on the log-fired cast iron range in the kitchen, a task which my mum hated but which, to her credit, she was good at. When electricity was finally installed by the squire in 1962, my parents celebrated by buying an Electrolux cooker and planned to use it for the first time to cook Christmas dinner.

Unfortunately, that was the year of the very bad winter and the power went off on Christmas Eve and did not come back on until Boxing Day. My mum had flatly refused to use the range ever again and so our Christmas dinner consisted of the ham salad that we traditionally had on Boxing Day.

To make up for the disappointment we went out for a family walk across the snow-covered fields and skated down the frozen brook to the village pub – fizzy drinks all round! It was one of my best Christmases.

Without water, we had to rely on the pump in the yard of the farm a quarter of a mile away and it was my job to make that trip once a day to bring back a bucketful to be stored in the cool of the pantry.

In the Great Drought of 1959 the pump dried up and the farmer had to get a water diviner in to find a new source of water. When it was found, he opened up a well and equipped it with a rope and bucket. I felt I was taking my life in my hands every time I threw the bucket into that hole in the ground

I didn’t have to worry for long though as the authorities soon arranged for an old aluminium milk churn to be filled with water and left outside our cottage every morning. In the sun. All day.

Tepid aluminium-infused tap water has a taste wholly different from the underground spring water that we had been used to from the pump, and it caused a few upset stomachs, but we didn’t complain as it was obviously well-meant.

Bathing was a weekly ritual on a Sunday evening. In the morning my dad would fill the brick-built copper in the washhouse from the rainwater butt at the side of the cottage. By evening the water was hot enough and the galvanised bath was brought in from the yard, placed in front of the range with a clotheshorse round it for privacy and filled up with buckets from the copper.

We took it in turns, in order of age, to bathe and it was a thoroughly dispiriting experience, made all the worse by the fact that, without fail, the indescribably dull Sing Something Simple with the Cliff Adams Singers was on the radio, followed by the equally unappealing Archers Omnibus. My misery was complete and it was the only time in my life I’ve actively looked forward to Monday morning.

The lack of water inevitably meant a lack of plumbed toilet facilities. Instead, we had an outside Elsan chemical toilet in a spider-infested shed. In the middle of winter, basic needs could be satisfied by a chamber pot in the bedroom, but anything more “substantial” meant a trip out of the kitchen, across the yard and round the back of the washhouse to the shed, escorted by my mum holding a hurricane lamp and singing ‘Bye Bye Blackbird’ outside the door to keep my spirits up while I was busy inside. To this day I can’t hear that song without feeling a stirring in my bowels.

Going home time

The school day ended with a brief prayer or hymn, usually ‘Now the Day is Over’, after which our time was our own. And there were so may ways to spend it – fishing for chub in the brook, climbing trees, scrumping, helping on the farm, earning pocket money potato picking (or spud-bashing as we knew it), swimming or just generally messing about in the brook.

We always enjoyed making a campfire and baking some potatoes on it, although I seem to recall that making the fire and baking the potatoes was much more fun than actually eating them.

© Jerry F, Going Postal 2021

Funnily enough, we never made any attempt to play proper games such as football (indeed I don’t think I even saw a football until I went to secondary school). This was probably because there weren’t enough of us and the only level ground in the village was the cricket pitch, and we certainly wouldn’t have been allowed on that.

© Jerry F, Going Postal 2021

Winter brought the added excitement of snow (it genuinely did snow every year in those days and in the bad winter of 1962 we were snowed in for three days). As well as snowball fights and making snowmen, we spent a lot of time sledging down a bank onto a frozen pond.

This activity was unfortunately banned after my older brother, who was steering with his legs at the front, caught his foot in a frozen cow’s hoofprint, causing the sledge and its passengers to pivot violently and his ankle to break.

Examinations

My last year at junior school coincided with the introduction of comprehensive education throughout the county and we were given a special one-off 11 Plus examination to determine whether we went to the new comprehensive school that had previously been a grammar school, or to the new comprehensive school that had previously been a secondary modern school.

I was fortunate enough to pass the exam and went to the ex-grammar school but, as both schools were on the same site, even sharing the playground and gym, and I travelled the five miles to it on the same coach as all my friends, it actually made little difference to me which one I went to.

The move to senior school, with its lengthy coach journey at the end of the school day and the time spent each evening doing homework, together with my rapid progress into my teenage years, and, probably the most significant development, my parents getting a TV, all meant that I began to spend less and less time enjoying all that my village and my friends had to offer until, seemingly in the blink of an eye, all that was over and I was packing my bags to leave home for London at the age of 17.

I would shortly be living just off the King’s Road in the centre of Chelsea at the height of the Swinging Sixties and would enthusiastically embark on that next stage of my life education.

But I would never forget what it meant to live in Barkby in those formative years.

© Jerry F, Going Postal 2021

There are many more memories – village parties, Bonfire Night, amateur plays in the Village Hall, going on holiday to Cromer or Mablethorpe on the train from Syston Station, school day trips to Speedwell, Treak Cliff and Peak Caverns in Derbyshire, having an hour off school so that we can all go and watch the Quorn Hunt Meet in the village, and still dozens more – but I must stop now as I’m afraid that if I go any further down the rabbit hole of my memories, I shall find it too hard to come back.

Would I really go back in time and do it all over again? In a heartbeat!

Without the incident with the prunes, obviously.

© Jerry F 2021