Earlier this year, we revisited The Potteries Museum & Art Gallery in Hanley, primarily because we wanted to see the Anglo-Saxon Staffordshire Hoard exhibits once again. Now living only a few miles away, a quiet day gave us a great opportunity. Seeing the exquisite workmanship of the Hoard was wonderful, and I may write something about this extraordinary series of finds at some point in the future but, since our previous visit, something new had opened at the Museum.

There’s a gallery that we’d not seen last time, and although relatively small, it really is a must see. In fact, you can’t easily miss it as the highlight, indeed the purpose of its existence, rather smacks you in the eye. Donated to the city of Stoke-on-Trent by the RAF to honour her designer, local man Reginald (R.J.) Mitchell, this is Spitfire RW388.

SharpieType301 2022

This surprisingly small and fragile-looking lady is getting on in years, having been built in 1945. Before moving to Stoke-on-Trent in 1972, RW388 spent some time as a ‘gate guardian’ outside various RAF bases, having been damaged during her last flight in 1952. Now she’s safe forever from the wind and rain but seems to sit gazing wistfully at the sky outside.

I had, of course, read the article GrumpyAngler wrote for our delectation, but I’ll admit that I really knew precious little of the history of this legendary and iconic plane and her sisters, and nothing at all of her designer and his connections to this area. Stumbling across the gallery was a great way for this to change, and my education started right here. Whether you are familiar with the Spitfire’s story, as I expect many of you will be, whether you agree with GrumpyAngler’s synopsis or stand in awe of what’s become legend, or know little of her but for her name, I hope you’ll enjoy the ride.

The Supermarine Spitfire, both the original design and subsequent iterations, is a British single-seater, short-range, high-performance interceptor, or fighter. The aircraft was designed by Reginald Joseph Mitchell, CBE, FRAeS, alongside a flock of other planes from the stables of the Supermarine Aviation Works, Ltd. These included flying boats and racing seaplanes. Mitchell worked for Supermarine for the best part of his adult life, from 1916 to 1936.

Mitchell was, by all accounts, a fascinating man, though one who, sadly, did not make old bones. Given his quite extraordinary achievements over his brief life, who knows what he could have gone on to accomplish had colon cancer not led to his untimely death, at the relatively young age of 42. Before moving on to the Spitfire, for which he is perhaps most famed, let’s take a look at this remarkable man.

Unknown, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

He was a Staffordshire lad, through and through. His origins lying a little way to the north of what is now the city of Stoke-on-Trent. A modest, and fairly shy man, he was born in 1895 in an unpretentious terraced house on Congleton Road in Butt Lane, at that time a small village on the outskirts of Kidsgrove. However, as the family grew, they soon moved and, together with his father Herbert and mother Eliza, his brothers George and Herbert (better known as Billy), and sisters Hilda and Evelyn, Mitchell grew up in a comfortable house in Longton.

A point that will not have escaped his father is that, even as a youngster, his oldest son was quite obviously bright. Herbert, a Yorkshireman, was in an excellent position to judge as he served as headmaster of three schools in the Stoke-on-Trent area, before resigning from teaching, becoming a master printer, and subsequently setting up his own printing firm.

The young Mitchell was known, as are many lads, to have a passion for building models of aircraft. Not with the sort of modelling kits with pre-formed pieces and careful instructions that many of us would be familiar with though. These were constructed from scratch, from careful observation and using whatever materials he could lay hands on. This simple, inventive boyish hobby, helping to develop excellent hands-on skills and 3D design-based spatial awareness, would stand him in good stead throughout his life.

He and his brothers were fortunate to be growing up in the earliest phases of aerial innovation and development, and the new-fangled planes were a particular passion of his. The Wright brothers’ first powered flight at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, had taken place in 1903, the year that Mitchell started school, and he was only a few years older when Louis Blériot made the first powered flight across the English Channel.

As a boy, Mitchell attended the local School Board’s Higher Grade Elementary school, at Queensberry Road, and showed considerable aptitude for mathematics from an early age. Higher Grade Elementary schools offered teaching for pupils above the compulsory leaving age which was, at that time, eleven. This school provided a semi-technical and more advanced education, with boys following an advanced elementary course at junior and middle school level.

Following his time there, in 1905 he moved to the co-educational grammar school, Hanley High School, studying subjects expected of such a school, including Latin and Greek, at a higher level. Rather appropriately, the School song was ‘Etiam Altiora Petamus’ (‘let us aim even higher’). This school has since been renamed in his honour though it had fallen upon hard times by the late 1990s. At that point, the school, now called Mitchell High School, had achieved the dubious honour of being one of the fifty worst schools in England for GCSE results.

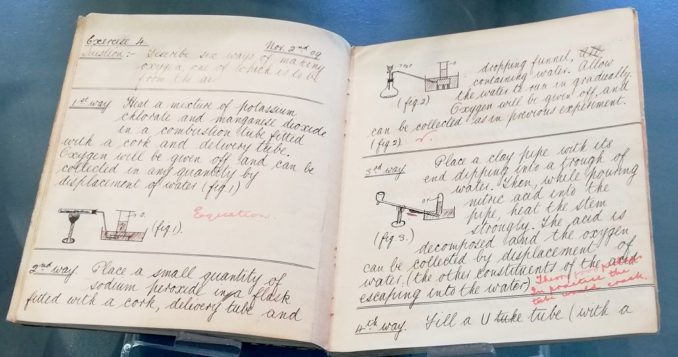

But the school was a great influence in Mitchell’s time, and his careful approach, methodical mind, and developing draughtsmanship can be seen, even by the age of fourteen. This is evidenced by pages from his school chemistry exercise book, now exhibited in the Museum.

SharpieType301 2022

He left Hanley High School aged sixteen but continued with his studies at evening classes, at the Wedgwood Memorial Institute, Burslem and Tunstall School of Science and Art, whilst serving a five-year apprenticeship. He had a strong academic bent so did well for himself. He studied mathematics, being awarded one of the Midlands Counties Union special prizes for this subject, mechanics, and technical drawing.

He was employed as a premium apprentice by Kerr, Stuart & Company Ltd., a local locomotive engineering works, at the California Works in Fenton. Initially, he was based in their workshops, learning his trade on the shop floor (and making excellent use of his newly acquired skills in his time off, as he built his own foot-powered lathe at home), before moving into the drawing office where he was soon recognised as a talented and innovative young designer.

The concept of a premium apprenticeship was a new one to me. In Mitchell’s time, while an apprentice received a small wage, they were often expected to find the money for their training themselves, unlike modern apprenticeships. Apprenticeships typically lasted between five and seven years. As the name suggests, premium apprentices paid their company a premium over and above the standard apprenticeship fee. In return, a premium apprentice received a combination of intensive practical (workshop) training with theoretical (classroom) teaching, with a view to progression into senior engineering positions.

After finishing his apprenticeship and leaving Kerr, Stuart & Co. in 1916, at the height of the First World War, Mitchell was taken on as personal assistant to Hubert Scott-Paine, the owner of the Supermarine Aviation Works, Ltd. So, leaving the Potteries behind, in 1917 he moved to Southampton.

Supermarine had, until just one year before, been Pemberton-Billing Ltd., a firm who initially manufactured motor launches, but whose owner, Noel Pemberton-Billing, and manager, Hubert Scott-Paine, shared a keen interest in aviation. These men were vocal advocates of the potential of powered aviation and were instrumental in the early development of seaplanes.

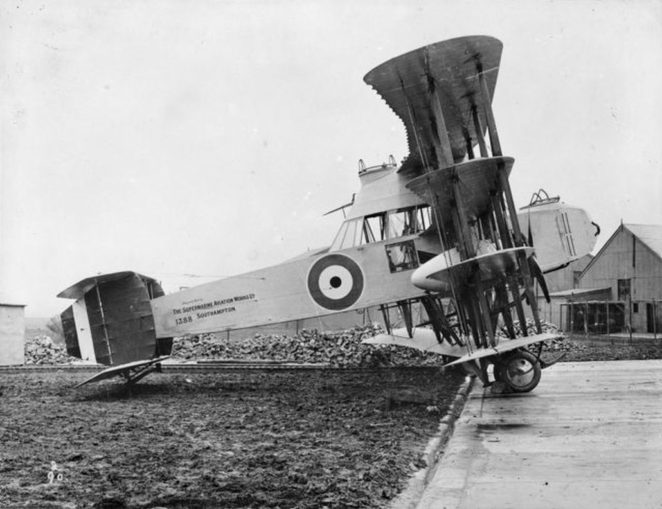

However, one of the first planes they had developed together was a prototype anti-Zeppelin night fighter, the heavily armed Supermarine P.B.31E Nighthawk. An absolute behemoth, this was built to carry a crew of four, two pilots and two gunners, as well as a considerable armoury. This rather archaic looking quadruplane, with a sixty-foot wingspan may appear ungainly now, and in fact never made it into production, but don’t forget that this period was still much within the early days of aviation history.

Australian War Memorial, image in the Public Domain

By the time Mitchell had joined Supermarine, the war was already in full flow. Although he was keen to join the firm, he had twice tried to join up, but was informed that his engineering training was viewed as being more useful than having him simply serve as ‘cannon fodder’.

Supermarine and his new boss, Scott-Paine, were fully engaged in the war effort, so were extremely fortunate in this assessment, and that their new boy was, in effect, exempted from military service! Indeed, there exist archived drawings which indicate that, despite having been so recently engaged by Supermarine, Mitchell had some involvement in the nacelle design on the Nighthawk.

So impressed was Scott-Paine with his new assistant that, almost from day one, Mitchell was afforded experience across a range of roles within Supermarine, rapidly subjecting him to every aspect of the business. Advancing quickly within the company, he made an immediate impact, and within a year he became Assistant Works Manager. He was promoted to Chief Designer in 1919, and then to Chief Engineer in 1920.

Without wishing to detract from his innate talent and rare brilliance, there was a likely contributing factor in Mitchell’s swift development. Supermarine had been assigned a contract to repair and build other manufacturer’s planes as part of the war effort. Not only were there the Supermarine designs to be studied and learned from, but he had access to blueprints from Short Brothers and the Norman Thompson Flight Company.

This meant he could study how other designers worked, affording him an extra level of education. By examining design features and technologies that he would not have encountered had he purely worked on in-house seaplanes, he rapidly soaked up additional knowledge.

The first entirely Mitchell-designed aircraft came in peacetime. In 1920, he completed designs for the wooden-hulled Supermarine Commercial Amphibian, a passenger-carrying biplane flying boat. The Amphibian was judged to be excellent in the 1920 Air Ministry competition, despite not taking first prize, with the aircraft having performed well. In fact, it was deemed the best of the three entrants in terms of design and reliability.

When comparing the Amphibian to the Nighthawk, already you can begin to recognise the progression towards the more artistic and streamlined designs for which Mitchell was renowned.

Unknown, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

Between 1920 and 1936, Mitchell designed (or redesigned) some twenty-four aircraft. With Supermarine being primarily a seaplane manufacturer, flying boats formed a good number of these, but light aircraft, fighters, and bombers also featured amongst Mitchell’s designs. Having honed his craft during World War One, Mitchell had great respect for the bravery of flyers. He was ever mindful of aeroplanes’ inherent fragility and was careful to integrate pilot safety, even when a design was optimised for speed.

Such was the reputation he built, Mitchell became near indispensable and when Supermarine was bought out in 1928 by Vickers-Armstrongs Limited, one of the conditions of the acquisition was that he remained in post as the company’s designer. He remained with this British aircraft manufacturer, which now became the Supermarine Aviation Works (Vickers) Ltd., for the rest of his life.

Mitchell was a complex man, described as a “curious mixture of dreams and common sense” by Sir Robert McLean, managing director of Vickers (Aviation) Ltd. A hard-working, focused, and pragmatic man, he was generally approachable, kind, and willing to listen to other points of view, though he didn’t suffer fools gladly. He was an inventive and intuitive designer, with a rare talent for getting to the heart of a problem and beavering away until a solution was achieved. He was also eminently practical. A stickler for things being ‘just right’, he could display quite a temper when his high standards and expectations weren’t met, but such storms were typically short-lived. He was a charming man, though he could be a little shy, but he was never pompous and got on with people from all echelons.

A Fellow of the Royal Aeronautical Society, he was appointed Commander of the Order of the British Empire in 1932 for his services to high-speed aeronautics. This award came after seaplanes he designed for Supermarine won the respected Coupe d’Aviation Maritime Jacques Schneider (a.k.a. Schneider Trophy) three times in a row in 1927, 1929, and 1931, thus securing the trophy for the UK permanently.

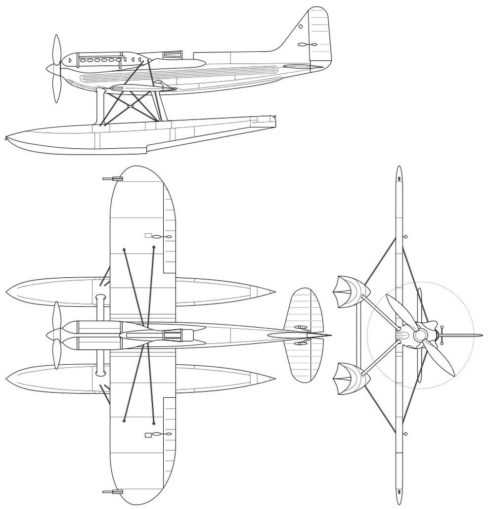

Kaboldy, licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

His 1931 winner, the Supermarine S.6B (at that time seen as the summit of Mitchell’s mission to “perfect the design of the racing seaplane”) was also the first aircraft to breach the 400-mph barrier, breaking the world air speed record.

The designs for his sleek racing planes, capable of high speeds, certainly informed later work. This included work he did on an initial design for the British Air Ministry, under their 1930 specification F7/30. The Ministry wanted a modern, all-metal day and night fighter, to replace outdated bi-plane fighters. The proposed new fighters were to be armed with four machine guns (initially) and have a superior top-speed and rate of climb. The plane the Ministry envisaged would have a landing speed of less than 60 mph with a short landing run and, most importantly, a clear, unobstructed view from the cockpit. Rather useful in a fighter, I’d say.

The plane Mitchell initially designed to the Ministry’s specification was the Supermarine Type 224 (which Sir Robert McLean dubbed the Spitfire, a nickname shared with his spirited elder daughter, his ‘little spitfire’, Annie) but Mitchell wasn’t happy with the performance of the end result. He knew that he could design a significantly superior plane so, even whilst the Type 224 was still being built, he was working on updated designs.

This work would result in the prototype K5054, construction of which started in December 1934. This was the first step towards what we now know as the Spitfire, the much faster, streamlined Type 300. A plane which, as McLean described it, was a “real killer fighter”.

Unfortunately, this period of Mitchell’s life was increasingly hampered by growing ill health. He was diagnosed with cancer in 1933 and underwent a colostomy, leaving him permanently disabled. He remained in considerable pain for the rest of his life but continued to work determinedly on the Spitfire, glossing over his illness to the best of his ability. Only Florence, his wife, was aware of the toll it took on him.

However, such was his passion for aviation that, though being told he may not have long to live, he began taking flying lessons, proudly obtaining his pilot’s licence in 1934, barely a year after his operation.

During the last year of his life, even with all this to contend with and with work on the Spitfire Type 300 still ongoing, Mitchell was also deeply involved with a second, major, and very different project. This, for a heavy bomber under a new Air Ministry specification, number B.12/36. Sadly, in 1936, he was diagnosed with a recurrence of the cancer and despite a month in Vienna to try to treat this, by early the next year he was forced to give up work. Reginald Mitchell died on 11 June 1937.

The bombers he designed were remarkably advanced, incorporating a number of novel features which would later become commonplace (for anyone interested in finding out more, see the Supermarine Type 316, Type 317, and Type 318).

The plans for them appeared promising and, four years after Mitchell’s death, work on mock-up fuselages was well under way when a German bombing raid on the Woolston factory completely destroyed them. It has been said that, had Mitchell’s designs come to fruition, this high-speed, four-engine, long-range bomber could have substantially bolstered the RAF’s strategic position in World War Two.

He died before he knew the results of the assessment of his design proposals for the heavy bomber. Nor did he see the first production models of his iconic Mk 1 Spitfire going into service with the Royal Air Force Number 19 Squadron, when K9789 was delivered on 4 August 1938.

RAF official photographer, image in the Public domain

Flight Lieutenant Richard Hillary wrote about the Spitfire, more specifically about his experiences with No. 603 Squadron RAF during the Battle of Britain in his book ‘The Last Enemy’. He was a young Spitfire pilot who, in just one week of combat, shot down five Messerschmitt Bf 109s, with two more probably destroyed and one damaged. His first impressions on seeing the fighter were quite emphatic. He remarked that “The dull grey-brown of the camouflage could not conceal the clear-cut beauty, the wicked simplicity of their lines.”

As to Mitchell and the Spitfire, before his death, he was aware that the Air Ministry had placed a massive order for three hundred and ten of his planes, a remarkable number in peacetime. However, this pales in comparison to what was to come.

The many tributes made to this extraordinary man after his death show the genuine respect and affection in which he was held, and these came well before his Spitfire played such a vital role during the Second World War. In many respects, Mitchell can be regarded as one of the great British heroes.

By the outbreak of WW2, over three hundred Spitfires were already in service with the RAF, with a further seventy-one in reserve and two thousand more on order. Over the twelve years it remained in production, more than 22,500 Spitfires in a variety of forms were built.

The only British fighter produced continuously throughout the war, Mitchell’s design continued to evolve in the capable hands of another Midlands man, his chief draughtsman, Joseph Smith CBE, who succeeded him as Chief Designer for Supermarine.

Smith directed the development of the Spitfire throughout its production history, through numerous variants (some 24 marks and many sub-variants), including the Seafire, the naval version of the plane. In the whole of its history there were no major failures of Mitchell’s basic robust and adaptable design. A rather remarkable record. In fact, Smith’s revisions and modifications to Mitchell’s original designs ensured that the Spitfire endured as a front-line fighter until it was eventually superseded by the development of jet fighters.

One of the interesting exhibits in the gallery at the Potteries Museum is a wall panel displaying some of the Spitfire’s key variants, each with a description of the maximum airspeed, weight, engine, and armaments.

SharpieType301 2022

Of these, the 1938 Mark 1A is the iconic Spitfire flown by ‘The Few’.

This was the original plane ordered by the RAF. Having already contributed significantly during the Dunkirk evacuation in May 1940, working at the extreme limit of its range, this was the plane which went on to participate in the Battle of Britain to such lethal effect.

The first major military campaign to be conducted entirely in the air, the Battle of Britain was fought largely over southern England. RAF fighter pilots were in almost daily combat with German planes from July until the end of October 1940. In the main, the RAF’s Hawker Hurricanes and Supermarine Spitfires were pitted against German planes like the dreaded Messerschmitt Bf 109, Heinkel He 111, and Junkers Ju 88.

The battle came about because Hitler was preparing for Operation ‘Sealion’ and the invasion of Britain. This plan meant that the Luftwaffe were hell-bent on destroying the planes and airfields which could defend our borders. It was a hard-fought campaign, quite brutal in many ways and the deaths and injuries sustained should never be forgotten. Just in terms of the aircraft, during the Battle of Britain, the Hurricane downed six hundred and fifty-six German aircraft, losing four hundred and four of their own. Spitfires accounted for a total of five hundred and twenty-nine enemy aircraft, losing two hundred and thirty planes in the process.

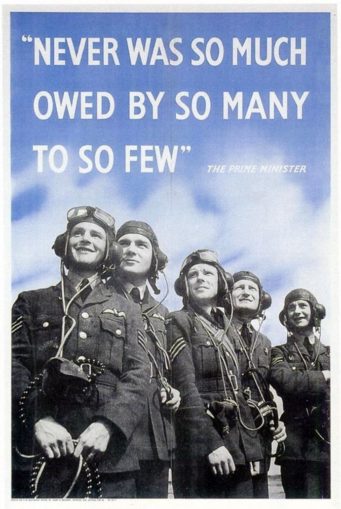

Although the RAF Hurricanes in service outnumbered the Spitfires at this time, Hurricane squadrons primarily targeted the German bombers while the faster and more agile Spitfires dealt with their fighter escorts, consistently outrunning and outmanoeuvring their opponents. This remarkable period prompted Prime Minister Winston Churchill to describe the efforts of the RAF with one of his most famous phrases:

H.M. Stationery Office, image in the Public domain

The Spitfire served not only as a fighter, but in a wide variety of different roles throughout the Second World War, and for years after it came to an end. It was valued not just by our RAF, but throughout the world. In fact, Supermarine Spitfires have seen service with Australia, Belgium, Burma, Canada, Czechoslovakia, Denmark, Egypt, France (including the Free French), Greece, Hong Kong, India (including as part of the British Raj Indian Empire), Indonesia, Ireland, Israel, Italy (including the Italian Republic), Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Pakistan, Poland, Portugal, Southern Rhodesia (as was), South Africa, the Soviet Union, Sweden, Syria, Thailand, Turkey, the USA, the former Yugoslavia and, of course the United Kingdom.

There is still much debate to this day as to which of the British fighters was superior, with many favouring the Hurricane over the Spitfire. For myself, I’ll reserve judgement, but when Generalleutnant Adolf Galland, the Luftwaffe’s lead flying ace and Messerschmitt Bf 109 pilot, was asked by Reichsmarschall Hermann Goering what he needed to win the Battle of Britain, he simply replied: “Spitfires“.

The Spitfire is an aircraft that has inspired and continues to inspire great respect and affection. Even the Wetherspoons pub in the Ironmarket at Newcastle-under-Lyme has a framed tribute to its designer, Reginald Mitchell, and the plane.

As for Mitchell, the British 1942 film ‘The First of the Few’ showed the public some aspects of his brief but noteworthy career. The film was produced and directed by Leslie Howard, who also starred as R. J. Mitchell. His co-star was David Niven, who played an RAF officer and test pilot.

Motion Picture Herald, image in the Public domain

There are books aplenty about the aircraft, its multitude of experiences and about the designer too. Mitchell’s son, the late Dr. Gordon Mitchell, published two books which tell his father’s story. Well worth looking out for, these are ‘R.J.Mitchell: Schooldays to Spitfire’ and ‘R.J. Mitchell: World Famous Aircraft Designer’.

Then there are models, models galore in fact, including 1/4 scale Spitfires from the Supermarine Works. I imagine that some readers might have had an Airfix scale model of one of the variants of this plane. That there is still considerable interest is shown by their 1:48 Spitfire Collection, and range of other models, still on sale today. I know many lads when I was younger spent hours meticulously following the instructions to construct their own model Spitfire, using all of those tiny plastic shapes on sprues in the box, carefully gluing, painting, and applying decals to the end result. I wonder how many bedroom ceilings still have drawing pin holes in place from this venture.

Ongoing interest comes too in the form of an expensive, high-end British watch. Bremont, best known for its luxury pilots’ watches, offer the S300, a vintage-inspired dive watch. This pays homage to British aviation roots, in particular its namesake, the prototype Spitfire fighter Type 300. They also offer a smaller version, the S301. This, of course, is very much to my tastes, sadly not to my bank manager’s!

Finally, the story of Reginald Mitchell and the Spitfire inspired one of the great British composers Sir William Turner Walton to write his ‘Spitfire Prelude and Fugue’ which you can listen to here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GVSm_f7bO8s&t=7s. Originally, it had been written as music for the 1942 Leslie Howard film, Walton later arranged it as a concert work. This was first performed at Philharmonic Hall in Liverpool in January 1943, conducted by Walton.

I shall leave the last words to Mitchell himself. A straight-talking man, he proclaimed that:

“If anybody ever tells you anything about an aeroplane which is so bloody complicated you can’t understand it, take it from me: it’s all balls.”

I rather think I’d have liked him.

© SharpieType301 2022