The name Dr Mary Temple Grandin may not exactly trip off the tongue, but her story is a fascinating tale of grit, stubbornness, a never ending will not only to survive but to thrive in a challenging world and, what’s more, achieve international recognition.

Now aged 75, this feisty lady is still an active designer-inventor, and an accomplished author. She has written some twenty books, two of which made the New York Times bestseller list, and has published over 400 articles in scientific journals and livestock periodicals. She’s acted as a consultant to prominent companies like McDonald’s, Burger King, Swift Meat Packers, etc. She’s also still in great demand as a world-renowned speaker. So, who is Temple Grandin?

Born in Boston, Massachusetts, in August 1947, Temple Grandin is rightly celebrated for her expertise in two quite different scientific fields.

She’s a Professor of Animal Sciences at Colorado State University, where for over thirty years she has studied animal behaviour and championed the humane treatment of livestock and ethical slaughtering practices. In fact, her work to promote better treatment of animals, particularly livestock, has covered well over half a century.

But she’s a champion in another sense too. One for autistic individuals and autism rights. Temple is herself autistic (in fact, she is an autistic savant) and has worked tirelessly to highlight the potential of autistic individuals as being “different, but not less”. She has long pressed to ensure that the autism spectrum is viewed as a neurological difference rather than a feared ‘disease to be cured’.

As contrasting as these two disparate specialities may appear to be, through Temple they are inextricably linked, as we shall see.

Peabody Awards, licensed under CC BY 2.0

Temple is a thoughtful, and immensely practical lady. She also has an impressive list of honours and awards. Amongst other things, she is a fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, has been named as one of ‘The 100 Most Influential People in the World’, by the iconic American ‘Time’ magazine (in 2010) and has had an Emmy Award-winning film (starring Claire Danes) made about her life.

Pretty amazing stuff for someone who, until she was nearly four years old was completely non-verbal. As an infant she couldn’t bear to be touched, could not make eye contact, and could only communicate her frustrations by humming, screaming, and flapping her hands. She was a child who showed all the signs of severe autism (something which was not, at the time of her birth, recognised). A child whose parents were told she was ‘brain damaged’, and that she should be ‘institutionalised’.

In truth, this piece is the not only the story of one extraordinary woman, but two. Temple is the one I’ll focus most closely upon, but her mother, Eustacia, is the other. Let’s kick off with her story.

Anna Eustacia Purves was born to a privileged family. She was intelligent, nice looking, talented, well-raised, and wealthy. She was a golden girl, the daughter of one of the men who co-invented the flux valve. Also known as the fluxgate inclinometer, this innovation became an integral part of the autopilot systems used in aircraft. Part of New England’s high society, Eustacia could count Winston Churchill, George Gershwin, and Robert Frost as acquaintances. A kind, empathetic young woman too, Eustacia read to a blind student in college and, no slouch academically, she graduated with an English degree from Harvard.

She married well, if perhaps unwisely in retrospect. Her husband, Richard (Dick) McCurdy Grandin, thirteen years her senior, was another wealthy man. Very much so, as he was heir to the substantial riches accumulated by the Grandin Farms wheat business (which had also dabbled in banking and oil), in the 1940s the largest wheat farm business in the United States.

As a newlywed, aged just nineteen, Eustacia fell pregnant. She gave birth to her first child, a daughter, when she was just twenty years old. She must have been overjoyed, and her burgeoning small family appeared to have been blessed. But she soon realised that her little one was not developing like other children so, as any mother would, took her two-year old toddler to see a paediatric physician at the Children’s Hospital in Boston This man was Dr Bronson Caruthers.

The hospital admitted Temple as an inpatient for ten days of observation. At the end of this period, Eustacia was told that her daughter Temple had brain damage and that there was little hope for her development. The child should be committed to an institution.

Give up her cherished baby? Hell, no! Eustacia was made of sterner stuff, so defied both her husband’s and Dr Caruthers’ advice and took her daughter home.

There were no therapy programs, as such, for children such as Temple, but Dr Caruthers had suggested that she might see a local woman, Mrs Reynolds, for some ‘speech lessons’. Eustacia took this on board, and as well as what would now be called speech therapy, provided Temple with intensive, one-to-one home schooling, using flash cards and constant repetition, love, and encouragement to focus on building skills and develop what Temple could do. This persistence paid off when, at four years old, Temple suddenly broke out of her silence and started to speak, using complete, logical sentences.

Eustacia was no pushover. She was quite clear about the behaviour she required and made sure Temple knew that there were consequences to not behaving as expected. She provided a well-structured, consistent home life for Temple. At first alone, then alongside her younger siblings (two sisters and a brother). That said, her husband, Dick, was anything but supportive.

In fact, he appears to have lived up to his name, being a bit of a… A rather an unlikable, character in many ways. A flawed man, with a renowned temper and utterly lacking in empathy. He couldn’t accept his little girl and often tormented her. At one stage, he also took notes about his wife’s behaviour, keeping this up for three years, then presenting the records to their psychiatrist to try to get Eustacia committed for insanity! It may come as no surprise that Temple’s parents divorced when she was 15 years of age.

Throughout, Eustacia retained high expectations of all her children. She insisted on Temple developing good manners, life skills, and social skills. As part of this education, when Temple was 8 years old, Eustacia insisted that she help out as a party hostess to further develop her social skills, ensuring she knew how to greet guests, shake hands, take their coats, etc.

Eustacia was a woman of great insight and stubbornness, and she believed in her child. It was her efforts which put in place the building blocks for her daughter to make the very best of her abilities.

Temple was fortunate that the school her mother chose continued with the firm, consistent, but nurturing approach Eustacia had initiated. In the 1950s, basic social skills (e.g. sharing and taking turns, not being rude, saying ‘please and thank you’, and showing good manners) were drilled into all children. This greatly benefitted Temple, and is a practice she promotes to this day, particularly when it comes to neurodiverse children. The little school’s teachers included Temple in every aspect of the school day, despite what was seen as her ‘oddity’.

As a visual thinker, one who instinctively sees and pays attention to the fine details in life, Temple was good at art (though lousy at maths) and loved ‘making things’. She was a very inventive child, and this aptitude has stood her in good stead throughout her life.

Although Temple flourished at kindergarten (our infant school), she struggled when she moved up to her next school. From interactions with just a handful of other children, she now had to cope with thirty or more per class, and a raft of different teachers. She didn’t handle this at all well. Her frustrations boiled over, so she was expelled for fighting.

Thankfully, her mother was financially secure, so was able to enrol Temple in a small boarding school in New Hampshire for ‘emotionally disturbed’ but gifted children, Mountain Country School. Although she continued to struggle with social interactions, being teased and bullied by other pupils, the school had a model farm. Here, Temple was able to engage in the hands-on, practical, outdoors tasks which relaxed her, and encountered the livestock she fell in love with and devoted her life to.

Here, particularly working with the horses she adored, she began to realise that she could notice and visualise small details in a situation, the minutiae that others simply overlooked.

So, thankfully, did one of her teachers, former NASA scientist William Carlock, who mentored and encouraged the shy, anxious young misfit. He channelled her teenage angst, frustrations around her social ineptitude, creative bent and fixations into constructive projects, and engendered in Temple a lifelong respect for science.

Another huge turning point in Temple’s life came when she was fifteen, and her Aunt Ann invited her to spend a summer at their ranch in Arizona. Though she was initially very apprehensive about going, amongst the ranch horses she finally found a place where she felt comfortable. In addition, her aunt’s empathy, and instinctual understanding of how to engage with Temple meant that she learned new skills, including how to drive!

Furthermore, the neighbouring ranch was a cattle ranch, and Temple discovered that she had a natural affinity with the beasts. The ranchers used a device called a cattle chute to keep their animals still and calm for vaccines and veterinary treatment. Seeing these large animals become quiet and calm once held by the firm pressure of the chute, she wondered whether it could help calm her own anxieties, so tried it.

Whilst human touch and affection still bothered her, making her panic, she found that the controlled (and controllable) stimuli of gentle pressure did help to relieve the tensions she so often felt. Once back at her school, she started to develop a similar ‘squeeze machine’ (which she sometimes calls her ‘hug machine’) to calm and soothe herself. Dr Carlock encouraged her experiments but made it clear that if she wanted to understand why it affected her in the positive manner it did, she’d have to learn science!

This started a journey into scientific literature and technical language that Temple took to like a duck to water. This logical approach made sense to her in a way that the nuances of conversational language and typical human non-verbal interactions never had. She’d found her niche.

She moved on to Franklin Pierce College to study Human Psychology and, whilst there she started to dig into all available research into sensory interactions to try to explain why her ‘hug machine’ had worked for her and investigate whether it would be effective in comforting and relaxing others. To this end, she built a foam-padded, human-scale prototype. This, she called PACES (Pressure Apparatus Controlled Environment Sensory). She recruited forty neurotypical (non-autistic) fellow students to test PACES, of whom sixty-two percent reported that being firmly held relaxed them. She knew that she was onto something so, being Temple, she published her results.

Temple used her ‘hug machine’ regularly, and gradually realised that she had begun to feel more comfortable with normal everyday human touch, the sort that you or I would probably take for granted. In effect, she was retraining herself, with its use, to tolerate the extreme hypersensitivity to sensory input she’d experienced but had never been able to handle whilst growing up.

Research into ‘deep pressure’ (now sometimes incorporated into furniture) and ‘weighted blankets’ to aid individuals react more favourably to sensory input (as part of sensory integration therapy) continues to this day. It appears to be of particular benefit to those on the autism spectrum, with ADHD, or who suffer severe anxiety. Compression garments (which employ a similar technique) have also been found to help treat dogs who suffer extreme responses to noise, like thunderstorms or fireworks.

Not content to rest on her laurels with her Bachelor’s degree, Temple moved to Arizona State University to study for a Master’s degree in Animal Science. This allowed her to incorporate the passion for animals that had started with the Mountain Country School model farm with her interests in psychology.

It was here, working part-time as a cattle chute operator to inform her studies, that she truly began to understand cattle. She soon realised that animal behaviour was the right field for her.

Livestock are prey animals, so have a wide field of vision and very sensitive hearing (this helps them identify potential predators as soon as they can). This means they will spook easily at anything they perceive as a threat. Temple’s ability to recognise, and empathise with, tiny changes in the way an animal acted, and what might have caused those changes was honed during this period. She started working on her designs for humane, curved livestock-handling facilities for slaughterhouses, which kept animals moving forward without fear since they cannot see the fate ahead of them. She was awarded her Master’s degree, in fact, it was one of the first in the world to have been awarded for a project on farm animal behaviour.

This stage had not been easy though. She was a woman in a man’s world, and the resistance her new-fangled ideas was strong. It didn’t help that her autism meant she thought differently and didn’t possess the customary social skills to suggest alterations diplomatically. She butted heads often in a battle of wills with the workers and managers at the companies she visited. But it did help that regardless of her apparent eccentricity, she was a strong, rangy, tall woman, not at all feminine, but willing and able to get stuck into any practical tasks that faced her. This, and the fact that she worked tirelessly, garnered her at least a grudging respect.

Eventually the good sense of her ideas became apparent. Efficiency won the day, and her designs were adopted, revolutionising the industry. Indeed, many aspects of them are still in use today. In fact, it was McDonald’s hiring Temple as a consultant in the late 1990s which finally cemented her reputation in respect to the ethical treatment of animals in meat production. They engaged her in an attempt to counter litigation from animal rights activists in what became known as the ‘McLibel case’.

Her next significant and successful project had come well before that though, in the late 1970s. This was a complete redesign and overhaul of dip vats, the equipment used to force cattle into pesticide solution to prevent scabies outbreaks. Traditional plunge vats always caused problems for the cattle, so much so that panicking animals not infrequently lost their lives, drowning in the deep liquid.

Temple looked at the process from a cow’s point of view and designed an innovative, completely new style dip system. This ensured that the animals would be completely immersed, as was necessary, but without experiencing fear. Non-slip flooring was an integral part of this (just think how much it makes us jump if our feet suddenly slip from under us!). Her design was a compassionate solution, but one which was also safer for the both the cattlemen and the animals they handled. It was adopted nationally and, today, the majority of cattle across the breadth of North America encounter the humane systems she designed.

Her PhD was conducted at the University of Illinois, where she focused still more deeply on animal behaviour. Here, she studied the impact environment has on animal behaviour and welfare (in this case, the animals were pigs, for whom she has great respect). Her work on the positive differences made to pigs’ welfare by providing a stimulating environment rather than merely existing in a ‘barren’ environment is enlightening. It doesn’t need to cost a fortune either. She observed that one thing pigs find infinitely fascinating is simply new straw, which they will explore and examine intently and happily.

Her findings showed that providing a rich environment had a marked impact on an animals behaviour and actually affected their central nervous system. From this, she concluded that the brain is extremely ‘plastic’ and is highly responsive to stimulation from the surrounding environment.

This concept of neuroplasticity (the brain’s ability to change and adapt in response to specific stimuli) is a very important one. Though radical in Temple’s time, it is now widely recognised and made use of in all kinds of therapies. Changes in the brain are physical and may involve rerouting or growing new neural networks. This has huge implications for brain recovery, to help mitigate the damage caused by events such as stroke or traumatic injury.

As a former member of an AWERB, an Animal Welfare and Ethical Review Body (goodness, that’s a few years ago now), it’s obvious to me that the work she did was ground-breaking and well ahead of its time. Albeit, my interest was the welfare of animals used in scientific research, but echoes of Temple’s work remain crucial to this day. Paying close attention to more than simply the basic ‘bedding, food and drink’ needs of animals used in scientific research forms an important part of the ‘refinement’ element of the important 3Rs principles (Replacement, Reduction and Refinement) so many people work hard to uphold.

In her own words, Temple explains why animals react to the world in the way that they do:

“Animals are sensory-based thinkers; they’re not word thinkers. It’s all about what they see, what they hear…. It’s a sensory-based world; it’s not a word-based world. Get away from verbal language, then you’ll start to understand animals.”

Further insight from Temple into the way animals think can be found in her 2019 talk which was given in Denver ‘How Horses & Other Animals Think’.

Over the years, Temple went on to examine, and improve, almost every aspect of livestock handling. Her livestock website makes for fascinating reading, as does her second site which deals with other aspects of Temple’s life.

As life moved on, it became increasingly apparent to Temple that she and other people processed information in a very different manner. This realisation overlapped with what she understood about how animals experienced and reacted to their surroundings. This, in turn, led her to engage in the second strand of work for which she became internationally renowned.

As she grew more confident that her own autism-driven differences were no barrier to creating a successful career, she started thinking about the reasons why there could be benefits to her, very different, way of thinking and working. She reasoned that some people are, like animals, sensory based, not word thinkers.

Could other people, with similar traits, learn to harness their own abilities and differences to live a more fulfilling life? Instead of concentrating on deficiencies and seeing a ‘condition’ or ‘disorder’ to be overcome, could the value of their differences be recognised, and harnessed as positive attributes?

She began to advocate on behalf of other people on the autism spectrum. She also started considering ‘thinking’ scientifically, eventually drawing the conclusion that there are three types of thinking styles common in people with autism (in fact, also in those considered neurotypical to a great extent). These are visual thinking (which is the way Temple operates), pattern thinking and word thinking. The types are nicely described by psychologist Kenneth Roberson, in ‘Three Thinking Styles Of Adults With Autism Spectrum Disorder’.

Each type possesses a unique set of strengths and weaknesses. Temple began to promote the benefits of valuing this neurodiversity, tapping into different kinds of minds. She encouraged including those on the spectrum for the benefits their differently wired minds can bring. Working together, different thinkers and their ‘differently abled brains’ can complement each other, like individual jigsaw pieces locking together to create the pictured goal.

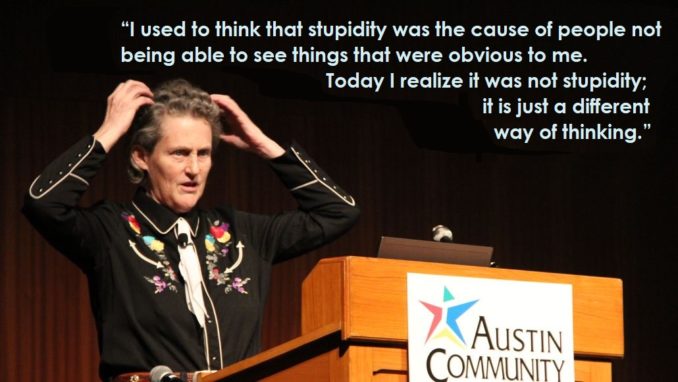

Adapted from ACC District, licensed under CC BY 2.0

This ties in surprisingly well with some of the leadership and management training I’ve encountered though my own career, examining personality types (e.g. Myers-Briggs personalities) with the goal of building teams where the strengths of each member are recognised and best utilised. Once again, in many ways, Temple was ahead of her time.

Temple has used many platforms to get her message across as widely as possible (her view is that too much emphasis is put on the deficits of autism, and there’s not enough focus on the strengths). She points out that many of the greatest creative minds the world has even known (including Einstein, Tesla, and many others) were misfits, and that if they lived today, they may well be called nerds or labelled ‘autistic’. She has been known to remark that we simply don’t know what talented people with autism might achieve in the future. After all, it affects people of all races, ethnicities, religions, and socio-economic backgrounds, across the globe.

She makes the point that ‘bottom-up’ thinking (focusing on the details before the overarching concept, and building up from there), something which is common to people with autism, has been recognised and seen as valuable, just in a slightly different way. A bottom-up approach (also called a connectionist approach) more or less defines machine learning and is used in training artificial neural networks (AI).

Her contributions around valuing difference include speaking at as many different venues as possible, the books she’s published and academics she has collaborated with (renowned neurologist Oliver Sacks being one of these). All these things have helped break down decades of stigma surrounding the ‘limitations’ which it was thought would always detrimentally affect people with autism.

Having worked closely with Temple, Sacks makes an interesting observation, that neurodiverse brains (including the autistic brain) “can play a paradoxical role, by bringing out latent powers, developments, evolutions, forms of life that might never be seen, or even be imaginable, in their absence“.

Ever the scientist, Temple, of course, wanted to understand the biological ‘why’ behind the strengths and weaknesses she saw in herself. What was actually happening in her brain, and what was it about this that made her the person she is? To this end, at the age of 63, she collaborated with neuroscientists from a number of institutions, undergoing a range of psychological tests and brain scans which employed a variety of imaging technologies.

The tests showed clear differences in her brain structure and function compared to three female controls who were similarly scanned and tested. Interestingly, the first point observed was that her brain was significantly larger than those of the controls, and the amygdala (the area which processes memory, decision making, and emotional responses, including fear) was unusually large.

The results are summarised in a downloadable poster ‘Dr. Temple Grandin: A Neuroimaging Case Study’ which makes fascinating reading for anyone interested in the brain. As an aside, it enchanted me to realise that her favourite song is Led Zeppelin’s ‘Stairway to Heaven’.

In 2021, Colorado State University opened a state-of-the-art equine facility with an indoor arena, stabling for nine therapy horses, outdoor runs, tack rooms, multi-use therapy rooms, clinical, and classroom space. This is the Temple Grandin Equine Centre. The facility offers a range of therapies. Foremost amongst these is, as you might imagine, hippotherapy (equine-assisted therapy), which is believed to help improve an individual’s strength, fine motor skills, cognition, and coordination, as the horse’s movement creates neurological changes, improving both physical and mental health. This view is supported by an expanding body of clinical research.

There’s plenty of data that simply being around horses (interacting with them, grooming, and riding them), particularly in the form of ‘adaptive’ riding programmes where riding is adapted to the needs of disabled individuals, is extremely beneficial. Indeed, this can transform an individual’s mindset and offer a greatly improved outlook for life. Hippotherapy, however, takes these benefits to a new level.

Horses are social animals. They are extraordinarily sensitive to those who ride them and can respond to a rider’s wishes almost before that person has consciously decided what they want to do next. There is a relationship built between rider and horse. A rider learns to become a careful observer of their horse’s behaviour and respond to the subtle cues their mount gives them. For the horse, all of the information they process is based on sensory input, through touch, pressure, body language, sight, sound, and in many other ways. That, in many ways, is similar to the way in which people with brain injuries perceive their world.

The therapy horses used by the Centre are themselves survivors. They are all rescues, some severely neglected, others almost killed by their former owners. Equine Sciences students from the Centre have spent time helping them recover from their trauma, to become gentle, confident, well-trained therapy horses.

Individuals come to the Centre from all abilities, ages, and backgrounds, but each one has developmental, physical, or emotional challenges, ranging from autism spectrum disorders, brain tumour, cerebral palsy, Down syndrome, and multiple sclerosis, to traumatic brain injury, and spinal cord Injuries.

Horses were extremely important to Temple from childhood. From working at Mountain Country School’s horse barn, she learned a sense of responsibility, a work ethic, a sense of purpose, and how to make friends. She found a wonderful sense of escape from a difficult world in horse-riding as a teenager. As she says herself “horses saved my life”. The Centre she played an instrumental part in bringing into being is one way to pay back that debt.

Temple is not only involved in this, and similar programmes, such as the Horses for Heroes ‘Cowboy Up!’ programme which helps veterans who have suffered from their time in service, but she continues to research further into animal behaviour. One of her recent projects is a collaboration with an Australian team to identify the genes that impact behaviour in horses. This study will focus on the American Quarter Horse, a popular and unusually versatile breed.

Temple has spoken widely about her experiences, how she has found her own ways to overcome what are seen as the challenges of being autistic, and also why thinking differently can be a gift. Her 2010 TED Talk ‘The world needs all kinds of minds’ gives you another taste of this extraordinary woman and an insight into what has made her the inspirational woman she undoubtedly is.

© SharpieType301 2023