International Festival of Glass, Stourbridge, August 2022

In Part One, I just about managed to shoehorn two days of the fantastic Festival. Before I carry on telling you about the rest, a quick gallop though the history of Stourbridge, and glassmaking, in and around the town might illuminate.

The town appears to be so named after an ancient bridge across the River Stour. The river, in earlier times, formed the boundary of the counties of Worcestershire and Staffordshire. But Stourbridge wasn’t always Stourbridge. It was formerly known as Bedcote since the original settlement fell within the feudal boundaries of Bedcote Manor. Indeed, the local Morris side (a mixed sex side who dance in the Cotswold style) are still called Bedcote Morris.

By 1255, the town appears with the spellings Sturbrug or Sturesbridge in the Worcestershire assize roll and was well-established as Stourbridge by the time that Huguenots refugees from Lorraine in north-eastern France settled in the area in the mid- to late-1500s, bringing their glassmaking skills and expertise with them, augmenting the small-scale domestic glass manufacture at nearby Cannock Chase in Staffordshire.

Stourbridge isn’t only known for glass, but also for coal and limestone, for leathercrafts, and woollen cloth (the town is encircled by hilly heathland well-suited to sheep, with plentiful water to wash the wool). Other industries include iron production (with nails and chain playing a major part), and the manufacture of firebricks made from the local high-quality fireclay. It was the availability of coal (for fuelling kilns) and the fireclay (to build furnaces and produce melt-pots) that made the area perfect for glassmaking.

Although now synonymous with ‘Stourbridge Glass’, no glass was actually made in the town itself. Right from the outset, the glassworks grew up on the edges of the town. Lye, Oldswinford, Hagley, Wollaston, Amblecote and Wordsley was where most glass manufacturing took place, together with Brierley Hill and Dudley.

A short distance to the east of Stourbridge, in Stambermill near Lye is thought to be the site of the first local glasshouse, built in 1614, called Colemans. Producing grand verre (window glass) and bottles, it was established by Paul Tyzack, on the banks of the Stour, for the princely sum of £8 for the house and £4 for the ovens. Tyzack’s glasshouse was perfectly positioned, as both coal and clay lay at different depths under the grounds.

Paul was the first British-born Tyzack, his name sometimes recorded as Paulle Tysacke, or du Thysac. His origins lie in one of the four French ‘Lorrainer’ families named in the ‘Glassmakers’ Charter’ (the others being Hennezel, Thietry, and Briseval). Glassmaking had long been considered a noble, esoteric art in France, and royal privilege granting quasi-noble status and ‘letters of privilege and liberties’ were awarded to ‘gentilshommes verriers’ (gentlemen glassmakers) from the Vosges region as early as 1369.

However, the families listed in the ‘Glassmakers’ Charter’, a clannish, fiercely independent, hot-headed, and secretive bunch, were most likely Huguenots, French Calvinist Protestants. As such, they became subject to religious persecution as Charles III, Duke of Lorraine, defended the Catholic faith in the lead up and during the French Wars of Religion. The Duke’s edicts frequently required immediate emigration from Lorraine, the total seizure of any property remaining, and the imprisonment of anyone who returned.

Thus, the ‘gentilshommes verriers’ families upped sticks and travelled to England en masse. There, intermarrying and with names Anglicised, they established new homes, initially settling in the Weald of Kent. Importantly, this area (and, in fact, Cannock Chase) had massive tracts of managed woodland that was required for glass production. I say wood, but it was actually charcoal, needed to give the high temperatures to form molten glass.

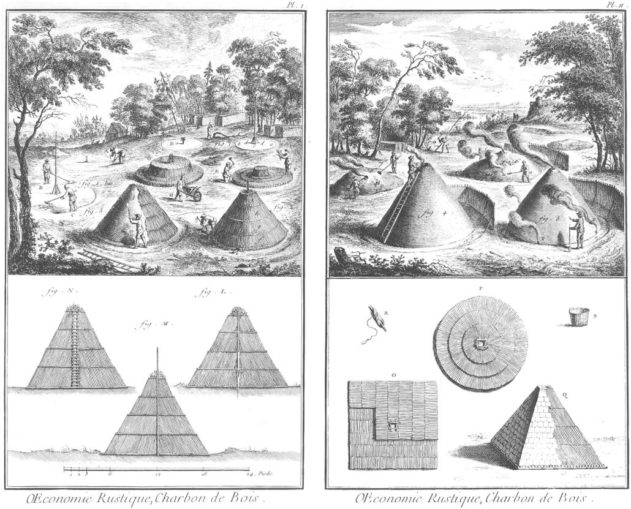

However, in 1615, glassmakers were prohibited from using wood as a fuel by order of King James I (he who authorised and directed the new English translation of the Bible). Charcoal, although it had been used for centuries for both glass and metalworking, is a resource-intensive and damaging material to produce—indeed entire forests could be levelled to feed production requirements. An early example of a reigning monarch’s interests in climate change, perhaps?

Plates from Encyclopédie by Diderot & D’Alembert, 1751–1772, Public Domain

The ‘Lorrainer’ families scoured their new country for suitable alternative locations and fuel sources for their craft. As the Stourbridge area fitted the bill nicely, the Tyzack, Henzey (Hennezel) and Tittery (Thietry) families relocated. Daniel Tittery established Holloway End glasshouse at Amblecote, one of the only surviving original 17th century factories. Thus commenced the gradual development of glassmaking.

As time went on, the glassmakers branched out into producing glass vessels, tableware, and more decorative items, and became respected members of local society and benefactors to their community. The 1670s development of lead glass, by George Ravenscroft of London offered an English alternative to expensive imported Venetian glass. This durable material, with exceptional reflective properties lent itself to cutting and engraving. It was soon adopted by the Stourbridge glass manufacturers and quickly became a mainstay.

The industry reached its peak around the end of the 18th century when steam power was harnessed to drive glass-cutting lathes. Glass workers came from far and wide to secure jobs in Stourbridge. The vast majority of people working in the industry were from Staffordshire, Warwickshire, Worcestershire, and Shropshire. Only a small percentage, around 9%, came from other parts of England and a smaller number still, perhaps 0.2%, from abroad.

By the late 19th and early 20th centuries Stourbridge crystal was celebrated the world over. In 1851, glassmakers displayed their wares at The Crystal Palace Great Exhibition at Hyde Park, for the first time showcasing their work on the international stage against rivals from Europe (France, Germany, Austria, and Bohemia) and America.

© Wellcome Images, licensed under CC BY 4.0

The last quarter of the 19th century was, perhaps, the Golden Age for Stourbridge glass. However, shifting models of global manufacturing, as well as changing fashions, led to a down-turn of the industry. By the late 20th and early 21st centuries, we had lost a number of the great, iconic names associated with glass. But even as late as the 1960s, Black Country glassmaking was described as the best in the country and is still recognised as amongst the finest in the world to this day. In 2012 Stourbridge proudly celebrated the 400th anniversary of the beginnings of the glass industry in the area! Stourbridge and its Glass Quarter is now part of the Black Country Global Geopark and has seen major investment in high-tech glass production at the Dial Glass Works, built in 1778, offering some indications that a new generation of glassmaking has begun.

But back to our Postcard…

There was a whole lot more to the Festival than we managed to enjoy. Talks and tours, glass demonstrations, and so much more. The East Asian theme included a gong bath (to melt away stress and tension, and leave you feeling deeply relaxed and refreshed, apparently), an evening of Japanese Taiko drumming, Kimchi making, a Taekwondo session with Master Jongho Kim, and a demonstration of Ganggangsullae (Korean traditional dance). It was slightly frustrating that we couldn’t do everything.

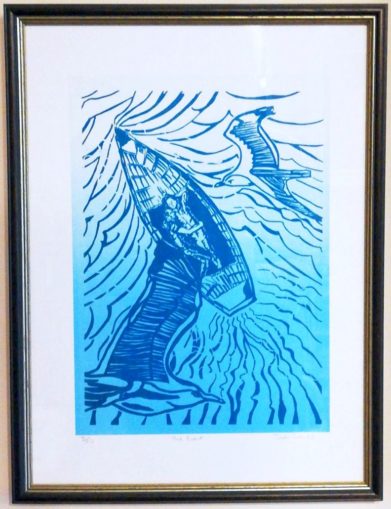

I was keen to go back to the studios at the Ruskin Glass Centre. Mike Allison’s printmaking studio was one of the attractions, as I’d spotted a print which I hoped might be for sale. Not by Allison himself, but by a printmaker he had mentored, Deb Gould. Although there are two people in the boat, this piece immediately brought to mind one of my favourite books, Hemingway’s ‘The Old Man and the Sea’.

© SharpieType301 2022

Thankfully, she was there in the studio with him, and I managed to speak to her. She seemed surprised that I was interested in her work, and I was gobsmacked when she told me the price, for a limited edition copy too, so the resulting transaction was conducted quick as a flash!

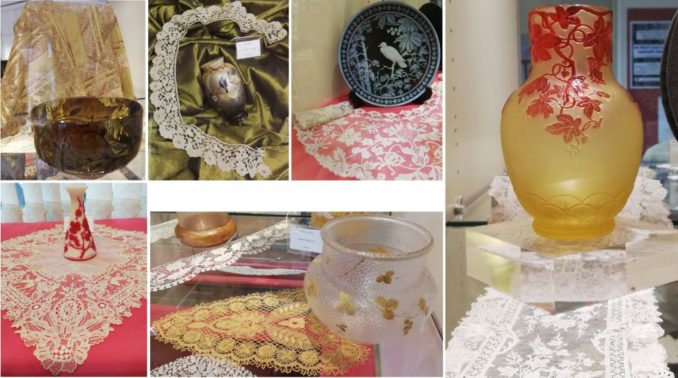

The next ‘must see’ for me was something that Mr S was not, initially, too enthusiastic about. This was the ‘Tales of East Asia’ exhibition at the Lace Guild, and textiles simply are not his thing. The exhibition was set out to marry the designs and shapes of lace from their extensive collections with glass objects from the private collection of Clive Manison. Primarily a collector of English glass, Mansion’s interest in the influence of Japanese art was piqued when he noticed a Japanese term in an auction catalogue. This led him to study ‘japonisme’ in depth, in relation to 19th century British Glass decoration. It was this aspect of both lace and glass which was explored by the exhibition.

© SharpieType301 2022

I won’t go into huge detail, but the photos above will give you an idea of the similarities in the designs of both lace and glass. I will say that Mr S was soon convinced that it had been a good idea to go to see it. Not least because of the volunteers who we met at the Guild. They were really welcoming, and wonderfully knowledgeable about the exhibits, their collections, about lacemaking in general, and passionate about their interest.

An unexpected bonus was that Clive Manison popped in to see the exhibition, and I was able to eavesdrop when he was explaining about the science and archaeology of ancient glass to the volunteers. I was good. I didn’t interrupt once!

Before we left, I got talking to one of the volunteers about the conservation of their collections, and the measures they’ve put in place to ensure its long-term survival. Once he realised that I had some knowledge, he invited us up to the Guild’s storage area where the greater part of the collections which are not on display are held. At that point we realised that we have ex-colleagues and acquaintances in common, and our lively chat carried on even after the building had closed. By the time we said our farewells it was coming on evening, and once again we were feeling pretty tired. Time to head for home… well, back to Brierley Hill, stopping off only to get something nice for dinner.

For the following day, the Sunday, we had another treat in mind. We had been in touch with another Puffin who lives locally and were going to meet for lunch in Stourbridge. Off we toddled on our customary number 6 bus, feeling more and more like locals ourselves as we passed now familiar landmarks.

We set off a little early as we had given ourselves some time to have a wander through the town centre. On that sunny Sunday morning, a fair number of people were out and about, and many cheerily nodded hellos or spoke to us as they passed by. It’s a friendly place, a moderately affluent town for the region, although it obviously took a hit during lockdown from which it has yet to fully recover. There’s a very long-established college, King Edward VI College, founded in 1552, still in operation to this day (it actually started life as the Chantry School of Holy Trinity in 1430, before its charter was granted). It has some lovely old architecture, and it offers regular Farmers’ and Craft markets. It seems a pleasant place to live.

We’d chosen to meet outside the Cock ‘N’ Bull on the High Street and sure enough, soon spotted our Wooshy heading towards us, with his customary big smile. It was great to see him again and, as all of us were ready to eat, we headed inside to peruse the menu. It’s a ‘burger and chick’n’ lover’s paradise, and we each soon found something to hit the spot.

The usual Puffin catch up and ‘putting the world to rights’ conversation continued between bites, but we decided that somewhere a little more traditional would be a nicer to relax afterwards. Woosh knew the very place, so off we headed through the town to Enville Street and the Royal Exchange.

One from the Batham’s stable, a small family brewery (six generations of brewers) which few seem to know about it, and this was a new one to me. A proper pub this, it hits you as soon as you walk through the door. Wood panelling, no irritating muzak, old photos on the walls and…, cough…, a typically more mature clientele. On such a lovely day, we had to sit outside in the pretty garden, and spent a happy while listening to the splashing sound of a small water feature.

© P L Chadwick, licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

Of course, we had a pint of Batham’s Mild, which I’m now aware is the one of finest of the fine. You won’t find this nectar bottled, and I’m now pretty convinced that you won’t find much better anywhere. This is decent beer, as I remember it from my youth, a beautiful deep ruby brown. At 3.5% ABV, it’s not a heavy hitter, but it punches well above its weight with a full flavour, and it went down a treat.

As Batham’s brewers themselves put it, quoting The Bard: “Blessing of your heart… You brew good Ale“

All good things come to an end and Woosh had a train to catch, so we headed back towards the station together. We decided that while we were on the bus, we’d go to the far terminus and have a look at Dudley as we’d never been to the town before.

Oh. Well, the bus station was certainly colourful. Jacob and his coat would have blended in without a by your leave with the range of ‘traditional’ costumes here. So, Dudley, the plus points first. There’s a 13th century castle, or the remains of one. Here it is.

© SharpieType301 2022

What else? Er, there was a legendary trilobite (an extinct marine arthropod) found in the limestone quarries of the nearby Wren’s Nest. Known as the ‘Dudley Bug’ it’s near unique to this area.

I’m struggling a bit now. OK, a lot, to be honest.

We didn’t take to the place. I know this was a Sunday afternoon but, conspicuously run down, the town was near deserted. Except, that is, for a small group of young men who I think (judging from appearances and the ungodly racket) may have been Afghan refugees, hanging around at James Forsyth’s Triumphal Arch Fountain in the Market Place, their boom box blasting out some sort of wailing ‘music’. We chose to walk well clear of them but were well aware of several pairs of dark eyes noting our passing. We did a quick march circuit of the town’s main street and headed back to the nearest bus stop. Sorry, Dudley, but I don’t think we’ll trouble you again.

The next day, our last, we had another treat to look forward to. We’d booked onto a canal bat ride, leaving from the jetty at the Festival car park. We arrived bright and early, to find the Phoenix, a canal boat operated from and by members of the Glasshouse College being made ready.

The college is part of Ruskin Mill Trust, an educational charity that offers outdoor learning environments, and makes use of practical land and craft activities to support the development of work and life skills in young people with autism and other learning difficulties. Our bargee that day was a shy young man who had been a student at Glasshouse.

Astonishingly, we were the only people who’d booked on for Phoenix’s first voyage. Wow, our own water taxi on the Town Arm of the Stourbridge Canal, we thought, but another couple came along at the last moment, so we did have a little company.

A downed tree which had fallen overnight meant we weren’t able to start of our trip by heading for the wonderful Bonded Warehouse (a late 1700s sturdy brick-built building with thick walls which held taxable goods like spirits, tea, and tobacco securely ‘in bond’ until the excise duty had been paid). A shame, but we did go up to Wordsley Junction, where the Stourbridge Canal’s main line (with its flight of sixteen locks taking the canal up the hill towards the former collieries at Pensnett Chase) meets the Stourbridge Town Arm heading south-east into the centre of Stourbridge town.

© SharpieType301 2022

The couple, who’d travelled up for the Festival from London, seemed very pleasant and were certainly interested in the canal and the history of the area. We were fortunate to have been joined on the boat by a gentleman who acted as an unofficial guide. A lovely old chap, he works on and off for the Ruskin Mill Trust now, but was deeply involved in glassmaking in Stourbridge, having worked as an engineer for the former Stuart and Sons Ltd. (a.k.a. Stuart Crystal) for many years.

He was delighted to share his wealth of knowledge about the glass industry, about life in the area then and now, and his own experiences. He told us that he was the person to lock the factory gates for the final time when Stuart closed in the early 2000s, and how he and his colleagues drowned their sorrows at Batham’s brewery tap, ‘The Vine’, on that fateful day.

He pointed out things we’d have missed completely as we slowly meandered along the waterway. He explained about the construction and workings of the canal itself, the canal boats and the people who worked them, and highlighted the wildlife and nature lining our route.

© SharpieType301 2022

He explained the relevance of the remains we could see of the old glassmaking factories we passed and told us about the glassmaking still being carried out alongside the canal. For example, specialist glassmakers Plowden & Thompson, sister company to Tudor Crystal, are based at the Dial Glass Works. Pointing out the iconic truncated glass cone (the top of the cone was removed in the 1930s), he explained that the company were technical glass makers who have supplied the medical, scientific, and aviation industries around the world, since 1922.

We passed moorhens and coots, ducks, and a grumpy swan, saw blackberries and an abundance of ripe elderberries overhanging the water and, briefly, the flash of a large fish swirling in the murky water. All in all, it was a wonderfully peaceful interlude and a joy to end our visit to the Festival.

There was still lots going on for the final day of the Festival, talks, demonstrations, and workshops, including a eurythmy performance of the romantic Chinese folk tale ‘The Cowherd and the Weaver Girl’ which I’d have liked to have seen. But we were all too aware that we had a train to catch so decided that we’d best make a move for home.

All that remained was for us to pick up our Driftwood Landscape, go back to where we were staying to pick up our already packed belongings and head for the railway station, riding that sweet little Stourbridge Shuttle a second time. Our train journey home, on a Bank Holiday Monday, was subject to the usual cancellations and uncertainties, but we reached home safe and sound… and absolutely knackered.

What a fantastic break it was. The next Festival should run in 2024, over the August Bank Holiday weekend, so if you’ve enjoyed this Postcard and would like to see more of Stourbridge and some incredible glass art for yourselves, we’ll probably see you there.

© SharpieType301 2022