Amongst a century of detritus at the BBC there lies some buried treasure. Between layers of fake news, preachy left-wing documentaries and un-funny comedy, the BBC’s iPlayer hides a gleaming gem of an old archaeology series. Each compact 30-minute episode follows the historical investigations, carried out both here and in distant parts of the Empire, of Sir Eric Robert Mortimer Wheeler CH CIE MC TD FRS FBA FSA.

Head of bog body Tollund Man,

Sven Rosborn – Public domain

Following his previous adventures in Rhodesia’s Great Zimbabwe and West Pakistan’s Mohenjo Daro, Sir Mortimer set aside safari suit and pith helmet to don his native tweeds and strike out to explore a mystery closer to home. The resulting 1954 documentary was introduced by Mr Glyn Daniel. Bedecked with bow tie and steel-rimmed spectacles, Mr Daniel announced the finding of a body in a heather-clad bog at a place called Tollund in North Denmark’s Jutland.

The body was of a naked man, wearing only a cap and belt. The cause of death? Strangulation, with a tightly bound noose still around the neck. Found by cutters at a depth of eight feet, the police quickly established this to be no recent crime and called in the archaeologists. Well preserved in the peat, the remains were taken to Copenhagen for investigation. Archaeologists there established the body belonged to the early Iron Age, 2,000 years ago.

How did he perish?

The camera cut to a rotating image of the corpse’s head. The remains of a cloth cap, rendered leathery by the passage of aeons, showed a few pieces of cloth finely stitched together. It was remarkably well preserved. “Quite extraordinary I think you’d agree,” commented Mr Daniel, a Cambridge University archaeologist and wartime photographic reconnaissance interpreter. “Is it the face of a criminal, a prisoner of war?” Or the victim of a prehistoric murder at the hands of an assassin wielding a noose of finely platted leather bound through a loop?

Above that noose sat a head as if of carved ebony complete with a day’s stubble around the chin. A remarkable expression of serenity lay across the face. Fine lines surrounding closed eyes suggested their owner separated from us by sleep rather than 2,000 years.

The camera drew outwards to reveal Sir Mortimer Wheeler in a dark suit and cardigan, collar and pale tie, swept back hair a la Heseltine and trimmed rather than curled moustache. Sir Mortimer was invited to give his impressions. “Haunting.” The head with its strong features was as if carved by a Rennacsince sculptor. Forgetting that they were closed, Sir Mortimer said he could feel the eyes following him about the room. With a twinkle in his own eye, Sir Mortimer mentioned the contents of the victim’s stomach had survived.

Mr Daniel then informed us that forty other ancients, along with other artefacts, had been found in similar circumstances in Danish bogs. The Buried Treasure team had been to Copenhagen to film and, via some recent Wiki archaeology, I have been able to reproduce some of the artefacts they captured.

Bronze Age horned helmets from Brøns Mose,

Simon Burchell – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

Man with a horned helmet,

National Museum of Denmark – Public domain

An impressive helmet with horns (top), this must have belonged to an important person. The design of a human face sits about the forehead. Between the horns is a slot to hold a crest of some sort. Tubes held plumes at the end of the horns. A bronze of a little warrior wearing a similar helmet from 500 BC (lower) who originally held a miniature axe. Full-sized axes are also found in the bogs.

The Gundestrup cauldron,

Rosemania – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

A most remarkable silver bowl originally with silver handles on the sides. Its panels represent Celtic gods – hunting gods holding boars or with reindeer in each hand. A Hercules-like god overpowers a lion. Dancing girls surround the gods. Interior panels contain more details, including armed men and trumpeters. A man, held by his ankles over what turns out to be a sacrificial bowl, has his throat cut.

An Eastern theme emerges with the representation of an elephant-like creature. The bowl is originally thought to be from the shores of the Black Sea having ‘somehow’ found its way to Denmark.

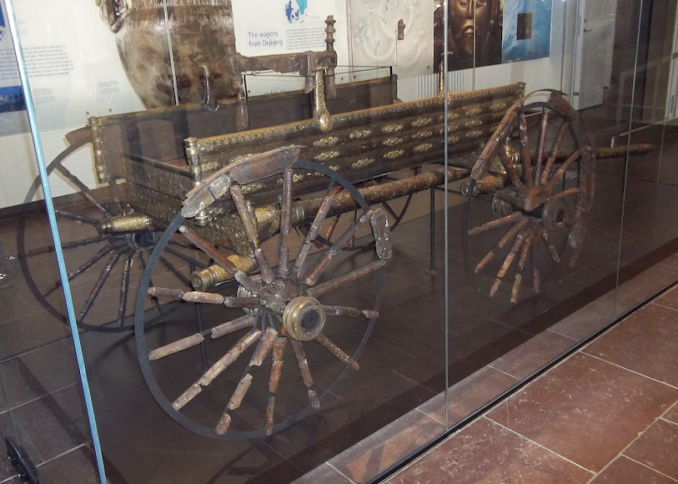

The Dejbjerg wagon,

Simon Burchell – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

The Copenhagen Museum also held a reconstruction of an unearthed wagon. Its wheels were single pieces of wood bent around and held with iron tyres. The wagon work was finely decorated with inlaid wood carvings. So finely decorated the assumption is it was used for religious and sacrificial purposes.

A bronze sun (below) is drawn across the heavens by a horse and cart. One side of the disk is inlaid with gold.

Solvognen, Æ.br.a. Trundholm mose,

Nationalmuseet – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

These artefacts are interesting in themselves, the presenters agreed, but also provide clues in the mystery of Tollund man. Sir Mortimer considered the alternatives. Was it murder? He understood from people who understood these things that this theory could be dismissed. Suicide? Hanged himself then drowned himself? Surely not. “He may well have been sacrificed,” concluded Sir Mortimer. Sacrifice was a familiar way of trying to influence the growth of crops in ancient times. Alternatively, Julius Caesar tells us the ancient Germans used to sacrifice prisoners of war. Another Roman historian had written of captured Romans being executed and drowned by the Germans. By local tradition, traitors and deserters were hanged. Cowards were drowned. “This chap might have been all three. One doesn’t know,” speculated Sir Mortimer.

The experts didn’t have the answer but they did have the well-preserved contents of the dead man’s stomach and, therefore, the ingredients of his last meal. A Miss Walley and a Dr White had worked it all out. Another miss, Noelle Middleton, had been appointed as Iron Age pre-historic cook. Wearing a polo-necked jumper and sensible skirt, she sat on an Iron Age folding stool in a reproduction of a kitchen of those times – a few logs and a cooking pot. In reality, far from being a cook, Irish-born Miss Middleton was a graduate of Trinity College, Dubin, and one of the first BBC television presenters. A big screen actress noted for ‘South of Algiers’ and ‘Carrington V.C.’, for Sir Mortimer’s gig she smiled to the camera and wished viewers a good evening.

Tollund man’s final meal had been eaten between twelve and twenty-four hours before death. It contained no trace of meat. Bourne out by the evidence of the time – a shortage of hunting weapons and bones – meat was in short supply. Previously those peoples had lived by hunting and fishing, but by Tollund man’s time there was very little game left.

The last meal was vegetable and consisted of the following ingredients, shown to us in the correct quantity on plates: barley, linseed (a well-known laxative worth soaking in salt or boiled in water and strained – just in case), camalino (?) seeds, mustard and pale lacacaria (?) which is found on waste ground. Also, smaller quantities of other seeds including those of the wild turnip and goats foot. Whatever that is.

Consumer advice from the first quarter of the twenty-first century – never eat anything you’ve never heard of and even the spell checker can’t spell.

“What are we going to do with them?” wondered Noelle. There was no sign of burning so they couldn’t have been roasted or baked. They can’t have been eaten raw, so she would boil them. Archaeological evidence from clay pots covered in crust suggested a sort of porridge.

She addressed the cooking pot and tipped in the ingredients along with two pints of water. Giving it a good stir, she proscribed low heat for ten hours. By now kneeling on the floor and leaning forward on clenched fists, Miss Middleton purred to the camera that she had another pot that she had prepared earlier. Dishing it up she suggested the porridge might have been accompanied by salt, honey or milk, none of which had left an archaeological trace.

Photo of archaeologist Glyn Daniel / Publicity still of actress Noelle Middleton,

Photographers unknown – Fair use: Provide identification, no alternative, low resolution

Fortunately, all of this was happening in black and white, but unfortunately Miss Middleton felt obliged to describe the concoction as “sinister purple/brown with speckles in it” which, if left to cool, might have become a cake of sorts. As for the drinks, the gentlemen invented an Iron Age Denmark-visiting Greek historian, who had committed to a long-lost parchment tales of mead and barley beer.

The camera cut to Sir Mortimer and Mr Glyn, bibs tucked into collars, divvying up the beer into horns in anticipation of their purple-brown speckled porridge cake. “Skol, skol,” the gentleman chimed. “It’ll break down resistance for the ordeal that is to follow,” warned Sir Mortimer prophetically.

It’s never a good sign when the cook won’t partake. Although too well-bred to abstain completely, it was noticeable that Miss Middleton had baggsed the smallest prehistoric bowl ever unearthed. Always the gentleman, Sir Mortimer invited Miss Middleton to start first. As was her prerogative, she declined. Mr Gyln stirred his portion about, pretending it too hot to eat. Sir Mortimer took the first spoonful.

“Is it delicious?” enquired Miss Middleton.

“No,” replied Sir Mortimer curtly. “Is anyone looking?” he added while covering his mouth.

After only half a spoon, Sir Mortimer dabbed his lips and took the opportunity to re-write the history books by declaring the poor chap of Tollund committed suicide on account of his wife’s cooking. A little more animal and too much vegetable, the diners concluded. Mr Daniel pushed his bowl to one side not having lifted the spoon from it and made further haste with the beer while declaring a toast to Tolland man.

“Good stuff, better than the porridge,” he concluded contemplating an empty horn.

Back to business. In 1821, a farmer in the Jutland village of Egtved found an oak trunk coffin containing the fully clothed body of a woman dating from the middle Bronze Age, over 3,000 years ago. The hair and teeth had survived. Saturated by water, clothes survived too and can be seen to this day in the National Museum in Copenhagen.

The remains were of a young, fair-haired girl of about nineteen years dressed in a jersey and skirt, covered in a blanket and wrapped in a cowskin along with some personal possessions. Also included – a bucket. Judging by the crystallised remains on its surface, the bucket had contained brandy wine. Besides that, the cremated remains of a child as well as pins, dress studs, a small knife and pebbles. A yellow flower suggested the burial had taken place in the summer.

Egtvedpigen at the Danish National Museum,

Tommy Hansen – Public domain

Replicas of the clothes had been made and allowed for a Bronze Age fashion parade. A Danish country scene was reproduced in the studio with straw on the floor, a couple of convincing trees and a theatrical backcloth depicting an English meadow in the 1950s. Miss Middleton’s clipped tones introduced Jean who tiptoed onto stage in bare feet and a very, very short skirt in the Danish Mid-Bronze Age style. ‘A two-piece suit in dark brown,’ chirped Miss Middleton, ‘A lightweight summer outfit complete with a giant bronze buckle.’ No doubt depicting some poor soul being slaughtered. Beyond it being ‘beautifully hammered and engraved,’ Miss Middleton spared us the blood-soaked details.

Platted hair ran well well down Jean’s back while complicated braids rested upon the top of her head. Practical for outdoor work and at the same time very elegant. Neat little jacket with elbow-length sleeves. Edges of the sleeves and neck over-sewn with scallop stitches. Charming corded wrap-around skirt. The ancients didn’t waste any material on that tiny skirt, made from the pure wool of the small goat-horned sheep and accessorised by two bronze bangles. An elegantly carved horn or wooden comb was carried in the belt. Jean wore a single bronze earring.

‘Altogether an elegant and practical summer outfit.’

Gordon was wearing the cloak gown and hat of the well-dressed Bronze Age man. The material was a dark brown natural wool, woven on an upright loom. His tall cap was made up of several pieces of cloth carefully sewn together. The cape was held across the chest by a large bronze pin. The gown underneath was held together by shoulder straps and a woven belt that went twice around the body.

How did those people live? The Danes had made a film, unimaginatively titled ‘A Day in the Danish Bronze Age.’ Blonde-haired children playing by a lakeside are interrupted by horseback traders arriving from Germany. Gordons armed with speers come out to meet them and exchange products. Amber necklaces and lumps of raw amber are bartered for finely made bronze axes and bangles.

Meanwhile, elsewhere bronze (a mix of 90% copper and 10% tin) is heated in a crucible over a campfire. It is poured into a two-part stone mould tied together with rope. After solidification, the mould is opened to reveal a rough bronze axehead ready to be trimmed and made into an axe proper by being attached to a wooden shaft and bound with rope.

The final scene is of a funeral with a coffin of wood trunk lined with cowhides surrounded by mourners and relatives. The body is laid into the coffin which is carried up a hill – hilltops being the ritual place for burials. Placed down, the exposed corpse is given personal and sacred objects and covered in a blanket before the cowhide is wrapped around. The lid is put onto the oak trunk for the final time.

Mourners and friends drift back down the hill leaving near relatives to pay their final respects. Subsequently, the coffin, still on the surface, is encased with loose stones and buried under piled earth to form a distinctive barrow.

Sir Mortimer liked the reconstruction. Ironically, the long dead bring history to life. We’re tempted to think of our ancestors as naked savages, but they had their art and their religion, their affection and piety, as we have today. They even have their trousers, he continued with a straight face. Very like ourselves in many respects.

Apart, he might have added, from the food.

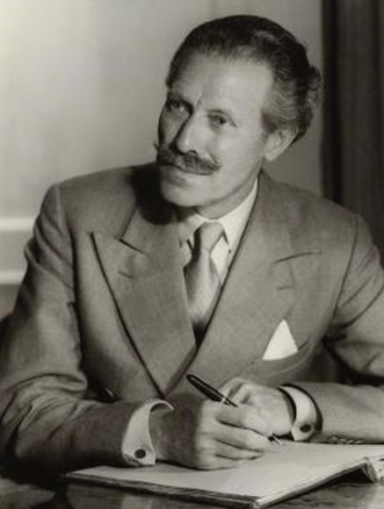

Photo of archaeologist Sir Mortimer Wheeler, 1956,

Howard Coaster – Fair use: Provides identification, no alternative, low resolution

© Always Worth Saying 2023