It has been a challenging couple of years for us all, and I suspect that our trials and tribulations are a long way from over. Thus, as the autumn temperatures drop away to winter’s chills, the leaves fall gold and red, and the days continue to shorten towards the end of another year, I find myself looking for simple pleasures wherever they might be, as a counter to the continuing craziness.

The last few weeks have been more of a test than I could honestly have expected, with Mr S spending some unwelcome time in the clutches of rNHS, and recovery being a frustratingly slow process. So, this morning, as the day dawned cloudless and sunny, I suggested that we make the most of it and take a breakfast picnic down to the Arboretum, Nottingham’s historic, beautifully maintained, and oldest public park.

A couple of flasks filled with good old Glengettie tea (those of you from Wales might recognise the name), two juicy apples cored and quartered, a slightly stale simit each, the Turkish sesame bread ring, and we’re ready to go.

© alexeyklyukin, licensed under CC BY 2.0

We walked down Raleigh Street, past the site of a little workshop which made diamond-frame ‘safety’ bicycles, as an alternative to the penny-farthing. These were safer to ride as the rider’s feet were within reach of the ground, making it easier to stop. When it was first set up in 1886, it manufactured three bicycles a week! Bought by cycling buff and lawyer, Frank Bowden, in 1887, this became The Raleigh Cycle Company, a world leader, which by 1949 was producing around 750,000 bicycles every year, the majority of which were exported.

A fantastic space, the Arboretum is spread over a small valley with hills to the north and south. It may have been the inspiration for Neverland portrayed in J.M. Barrie’s classic children’s tale ‘Peter Pan’, as he lived in Nottingham, working on the Nottingham Journal in the 1880s, before he wrote Peter Pan. The Arboretum was designed by a well-known nurseryman, botanist and botanical publisher, Samuel Curtis (1779-1860), then was laid out by Nottingham Town Council on land set aside by the Inclosure Act of 1845.

Though the weather was considerably cooler than the last few days had been, we were well wrapped up. We found ourselves a bench in the sunshine, overlooked by the War Memorial at Nottingham High School. Although no longer at its original site, the school has a long and interesting history. Its Charter was granted over five hundred years ago to the day as King Henry VIII put his seal to the school’s foundation deed on the 22 November 1513. Then called the ‘Free School’, it had been founded as a school for boys by Dame Agnes Mellers (alternatively recorded Mellors, Melleurs, Mellours, and more), after the death of her husband Richard in 1507, though records exist of a school dating back to 1289.

Image from Wikipedia, Public Domain

Richard Mellers was originally a brazier, likely a potter, and dealt in metal pots and dishes. He also became a bell-founder and owned the largest church bell-foundry in the region. Rather an unscrupulous businessman, in his efforts to accumulate personal wealth he appears to have swindled many of his customers. Indeed, he received a pardon in 1507 for having committed offenses against the statutes of weights and measures, probably relating to the purity of the metals used in his bells. His widow, Dame Agnes, was a pious soul, and is said to have founded the school to atone for wrongdoings against the people of Nottingham.

Despite this, or perhaps because of it, Richard had served as Sheriff of Nottingham (1472-73), Chamberlain (1484-85) and Royal Commissioner, and served as Mayor of Nottingham twice (1499-1500, and again in 1506-07).

Some of the school’s former pupils are equally interesting characters, the writer D.H. Lawrence being amongst them. Many of you may have heard the name Albert Ball, the ace WW1 fighter pilot awarded the Victoria Cross for his actions. Other pupils include Conservative politician, Kenneth Clarke, who served as Home Secretary, Chancellor of the Exchequer and Lord Chancellor, and the Labour politician, Edward ‘Ed’ Michael Balls, who became Shadow Home Secretary and Shadow Chancellor of the Exchequer.

Poor Henry Garnett, a former pupil who grew up to become the principal Jesuit of England, was executed for his involvement in the 1605 Gunpowder Plot. Talk about a cleft stick, the unfortunate man had simply heard of the plot’s existence through a confession, which of course was completely confidential, thus he didn’t inform the authorities. Regardless, he was convicted of treason and sentenced to death.

Another illustrious old boy was Puritan, Colonel John Hutchinson. A pupil from 1626-1632, he became MP for Nottinghamshire in 1646. A Commissioner of the specially convened High Court of Justice, he acted as one of the judges at the trial of Charles I, which was held in the Painted Chamber of the Palace of Westminster. In total, 135 Commissioners had been nominated to sit in judgement of the King. Some had been informed beforehand and refused to participate, but most were simply named without their consent. On the 27th of January 1649, John Hutchinson was 13th of 59 Commissioners to sign the King’s death-warrant. On 30th of January, Charles I was beheaded outside the Banqueting House in Whitehall.

The wooden bench we chose to sit on was a short distance from the Bandstand (venue to an assortment of silver and brass bands over the years) and was sheltered by a Blue Atlas Cedar from the increasing wind. Looking down the slope across the grass, the autumnal hues were gorgeous as the range of trees of different species, evergreens and deciduous, added extra texture and colour against a clear blue sky.

A few hardy dog walkers passed by, like us, bundled up in hats and scarves, their dogs looking a lot more enthusiastic to be out than the owners! Most people smiled though or said good morning. How wonderfully normal.

An unkempt and grimy gentleman in a wheelchair trundled along the path towards us from the Arboretum gates. Poor old soul was almost certainly a resident from one of the nearby hostels. He wore only grubby trackie bottoms and a t-shirt, but didn’t seem to feel the chill, though he obviously had some serious health problems. Missing one leg, he had the most alarming smoker’s cough, doubtless exacerbated by the smouldering roll-up drooping from his lips. When he could speak, he muttered hello, but he didn’t seem to want a conversation. Instead, he chuntered on to himself in the angriest monologue I’ve heard for some time, repeating himself about fraud and the Department for Work and Pensions, his rant fluently peppered with expletives.

No, this isn’t him, by the way… this is another old dosser I spotted (looks carefully over shoulder…).

© SharpieType301, 2021

Once we’d polished off our tasty repast, it was time for a wander. To be honest, it was getting a little nippy as the wind had picked up. This however, made for the most beautiful sight. The central avenue through the park is lined with mature lime trees, in fact these are surviving remains of the original collections, and although many of the yellowing leaves still cling to the branches, the grass below them is carpeted with those that have already fallen. As the wind blew, it lifted the leaves into a golden, shimmering magic carpet, rippling, and shapeshifting before falling back to earth.

We walked the length of the top path, along the Dahlia Border. Now sadly a shadow of its past glory, it will be magnificent again next year. Only a few blossoms still remain, but these are a lovely reminder of late summer.

© SharpieType301, 2021

The morning sun backlit one flower, giving its creamy pink petals an otherworldly luminous radiance. Very sculptural flowers are dahlias, like naturally symmetrical works of art with incredible variety in their shapes and shades.

© SharpieType301, 2021

Native to Mexico and Central America, dahlias are relatives to sunflowers, daisies and, of course, the chrysanthemum. In the late 1700s, French botanist Nicolas-Joseph Thiéry de Menonville, whilst on a daring mission to Mexico to purloin the cochineal insect (a valuable treasure for the scarlet dye it produced) mentioned ‘strangely beautiful’ flowers he’d seen in a garden in Oaxaca.

By 1802 Kew Gardens had received tubers of these exotic and glamorous plants, and soon afterwards the formidable Elizabeth Vassall Fox, Baroness Holland (a great friend of Georgiana Cavendish, Duchess of Devonshire), became instrumental in raising the popularity of these perennial blooms, and establishing their permanent presence in British gardens. Within a few decades dahlias were popular and well established. In 1824, Lord Holland penned a note to his wife, declaiming:

“The dahlia you brought to our isle,

Your praises for ever shall speak;

Mid gardens as sweet as your smile,

And in colour as bright as your cheek.”

A little further on our walk, we spotted another flower which showed a sunburst of warmth, a floral firework exploding with colour.

© SharpieType301, 2021

As we ambled through the Arboretum, kicking through the rustling leaves as we went, we stopped by the statue of Feargus Edward O’Connor, a man regarded by many as one of the founders of Chartism, standing quietly beneath the trees.

Chartism, so named after the People’s Charter of 1838, was a national protest movement which trusted constitutional methods to secure its aims, rather than insurrection. What O’Connor and the Chartists put faith in was overwhelming the authorities by a show of numbers. They argued against political corruption, but also for democracy.

Democracy, a term from the Greek, combining dēmos ‘people’ and kratos ‘rule’, was perhaps best defined by 16th President of the United States, Abraham Lincoln, in the concluding words of his 1863 Gettysburg Address, expressing his desire that:

“Government of the people, by the people, and for the people, shall not perish from the Earth”

The foundations of the democracy in which he believed include freedom of assembly, association and speech, the explicit consent of those governed, voting rights, and… wait for it… freedom from unwarranted governmental deprivation of the right to life and liberty.

I rather think old Feargus would have been a damn fine Puffin, and his views may appeal to many of us in the circumstances we see today. Perhaps we might find a new Lion of Freedom to rally around, and revise the song written in his honour:

“The Lion of Freedom is come from his den;

We’ll rally around him, again and again;

We’ll crown him with laurel, our champion to be:

O’Connor the patriot, for sweet Liberty!”

In 1837 O’Connor founded the Northern Star and Leeds General Advertiser newspaper in Leeds. Aimed at the working classes, petitioning for the right of the common people to have their voices heard, the Star promoted the tenets of Chartism across Britain and quickly became the most widely read provincial newspaper in England.

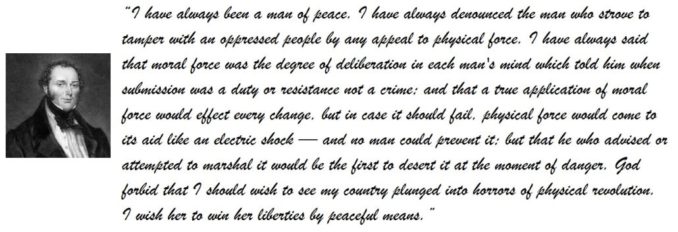

Image from Wikipedia, Public Domain

A controversial figure in many ways, O’Connor was a charismatic man, a spirited advocate for the people, combining canny campaigning with consummate eloquence. An imposing figure of a man at over six feet in height, powerfully built and athletic, he was a natural leader. A fiery red head, an exuberant, charming, self-confident, defiant, and passionate man. He dominated any public gathering, so it is no surprise that when he spoke at meetings, he attracted massive crowds. He long remained a thorn in the side of the Establishment and had rapidly become known as the ‘Lion of Freedom’.

O’Connor was no advocate of revolution, however. He well-understood the distinction between ‘moral’ and ‘physical’ force and applied this perspective to his guiding principle that protest should be ‘within the law’. Not least, the unsuccessful November 1839 Newport Rising (perhaps a tale for another day) had demonstrated to him the folly of an armed uprising where an untrained horde, ill-equipped with homemade pikes, bludgeons, and firearms, stood against the concerted forces of the State. Twenty-four of the Chartists were killed or later died of their injuries during the Rising: more than those killed at the Peterloo Massacre.

In the repression that followed, O’Connor was arrested. Despite denying prior knowledge of the plan, O’Connor was blamed for encouraging the leaders (John Frost, Zephaniah Williams, and Williams Jones) of the Newport Rising, the last large-scale armed protest in Great Britain. For his pains, he was incarcerated for ‘seditious libel’ at York Castle’s notoriously brutal and corrupt prison (a delightful venue wherein prisoners were beaten so badly by gaolers that they died, and where highwayman, Richard “Dick” Turpin was executed).

© SharpieType301, 2021

Having served as MP for Cork County between 1832 and 1835, he was elected to Parliament as the MP for Nottingham in July 1847 and went on to serve the people of Nottingham between 1847 and 1852, when the Chartist movement regained momentum. He was a respected man, but he could also be pompous, vituperative, and egotistical.

Towards the end of his life, he became increasingly unpredictable and his erratic behaviour a cause for concern. He was accused of assaulting three MPs in 1852, one of whom, Sir Benjamin Hall, Tory MP for Marylebone, was struck whilst speaking in the House of Commons. He suffered a mental breakdown and was committed to the Manor House Asylum in Chiswick. The great personal pressure he’d worked under unrelentingly for the Chartist cause and heavy drinking may have been instrumental in this, but it’s thought possible, perhaps likely, that this change in behaviour stemmed from GPI (general paralysis of the insane). Also called paralytic dementia, this is a severe neuropsychiatric disorder caused by late-stage syphilis. He died aged just 59.

Further on through our walk we reached perhaps the best-known feature of the Arboretum, the Chinese Bell Tower. Built in 1862, with a tiled octagonal cupola, it sports a Russian cannon at each corner, two of which were captured at the siege of Sebastopol, in 1859.

© SharpieType301, 2021

The tower, with a Russian inscription around the roof and an English inscription around the base, commemorates the Nottinghamshire Regiment’s involvement in the Crimean War and the Anglo-Chinese ‘Opium’ Wars (1857-1861). The original bell was ‘acquired’ by the 59th (2nd Notts) Regiment from a temple in Canton but was moved to the Regiment’s Museum in 1956. Today, a replica bell hangs from the tower—probably just as well, given the somewhat dubious characters and local youths who still view the tower as a favourite spot to hang out in.

At one time, the slope below the Chinese Bell Tower held the Rose Garden. This faintly disappointing space lacks roses now but the garden was designed in 1972 on the site of old greenhouses to commemorate the many rose-shows once held in the Arboretum.

More recently the Arboretum has hosted the Nottingham Green Festival, street food festivals, and Arboretum Sunsets events which included concerts from Spandau Ballet’s Tony Hadley and Fairport Convention’s Richard Thompson.

Slightly downhill from the Bell Tower is a surprise feature, of which there are several in the park. This might have been carved by Mark Manders, a Nottingham-based sculptor come chainsaw woodcarver (please correct me if you know otherwise). The gnarly barked stump of what I think may well have been one of the original London Plane trees has been carved into wonderfully quirky natural designs.

© SharpieType301, 2021

The bifurcated trunk has a sleepy-faced owl peeping out of one side, high above my head, and the bottom of the bole bears beautifully carved foliage and a snoozing rabbit nestling between its roots.

© SharpieType301, 2021

By now, we had the distinct feeling that we’d seen the best of the day. That northerly wind had started to draw streaks of greying clouds across the sky and carried a definite wintry bite. Time to think about heading for home, but no visit to the Arboretum can be complete without chatting to the natives (OK, interlopers, for you pedants).

© SharpieType301, 2021

In days gone by, some famous residents could be seen at the Arboretum. Henry the Goose was one apparently notable attraction, and the Circular Aviary was the home of another, Cocky the cockatoo. He was the legendary Sulphur-Crested Cockatoo who delighted in calling “goodbye Cocky” as people passed him by.

My brother-in-law, who lived on Raleigh Street for a while, fondly remembers being taken to visit Cocky as a child. The bird lasted longer in Nottingham than my brother-in-law, an RAF brat who travelled far and wide. Cocky lived on until 1968, allegedly falling off his perch at the grand old age of 114. The aviaries are still there, and although the Circular Aviary has a bizarre art installation of brightly painted plastic birds, you can still tweet sweet nothings to the budgies, canaries, zebra finches and cockatiels in the row of aviaries alongside.

Just opposite the caged enclosures is the small pond with its central fountain, looking considerably better now for being cleaned up last year. Despite the notices, small children still bring bread to feed the ducks, though the pigeons and seagulls sometimes give the poor mallards stiff competition. I’m told that there were a few terrapins in the pond at one point—remnants from the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles craze, perhaps?

© SharpieType301, 2021

By now we had both begun to get quite cold and more than a little tired. This recovery lark wears you out, you know! We headed homewards alongside the General Cemetery, plodding uphill along Cromwell Street. There was still a little sun slanting through the trees in the Cemetery, and this highlighted a pretty yellow trailing plant against the softly warm honeyed colour of the local sandstone. I’ve no idea what it is, but it certainly made me smile.

© SharpieType301, 2021

A welcoming lunch of homemade soup awaited us, with a hunk of freshly made seedy bread still warm from the oven. A treat indeed, made more special by the fact that Mr S had been able to recall some of the skills and memories lost during his illness to prepare it for us. Exactly one of those ‘simple pleasures’ I referred to at the start of this piece.

© SharpieType301, 2021

As we enjoyed it, I thought about what we’d seen in the Arboretum, particularly the half-hidden statue of the ‘Lion of Freedom’, Feargus Edward O’Connor, and what he had fought for. With what we face now, his words resound with me perhaps more strongly than ever before, so I will leave you with a quote from him:

© SharpieType301, 2021

© SharpieType301 2021