I’d like to begin by introducing you to a rather special lady. She was born in February 1957, the first of twelve sisters. A real local lass, she lived and worked from the Humber all of her life. She’s a sturdy old girl, showing her age a little now but growing older gracefully as befits her feline name. She, of all her siblings, is the one who has had the most prolific career.

Figure 1: The Ross Tiger

© SharpieType301, 2022

She sprang to life at yard No 1416, at the shipbuilders Cochrane & Sons of Selby, just across the Humber in Yorkshire, a company who were earlier heavily involved in designing and constructing the WW II Mulberry harbour units. We made her acquaintance in the company of a lovely gentleman by the name of Bob Formby, on a chilly January morning aboard the Tiger at her permanent berth in the Alexandra Dock in Grimsby.

This is Tiger’s home port, and she is the star attraction at the Grimsby Fishing Heritage Centre. I’d say that Bob, conducting a tour of the Tiger that day (in fact, for just the two of us as it wasn’t a wonderful day) may well be a rival star. With fifty years at sea, from deckhand on the Tiger to Skipper of a number of ships, including another ‘Cat’, he’s a Master Mariner with complete mastery of his subject. We learned such a lot from an enjoyable hour spent with this expert and engaging man.

A visit to the Grimsby Fishing Heritage Centre was the highlight of our trip to North East Lincolnshire, an area of which we knew precious little. The staff we met there were wonderful, from Aaron who cheerily welcomed us, to Andrea and Debs on standby with a pot of Stokes’ tea and delicious Lincolnshire Plum Bread topped with a generous slice of cheese and, of course, Bob.

Figure 2: Tea and Plum Bread

© SharpieType301, 2022

After a walk through the exhibition spaces with local collections and a brief history of ships and sailing, the Centre is laid out as a series of tableaux. This allows you, the visitor, to experience the sights, smells and sounds of the heyday of this famous port by signing onto a trawler as a crew member.

This clever concept begins as you, our intrepid trawlerman, step out of your 1950s Grimsby home, passing a young woman ‘braiding’ the nets in the back yard, an essential part of the industry to make or repair nets before the advent of mass-produced ones.

Figure 3: Braiding the Nets

© SharpieType301, 2022

In truth, you’d likely pass whole streets of women (wives, grannies, mothers, sisters, and daughters) all busily braiding on your way to the docks. You’d hear them nattering, as they kept a weather-eye on the antics of the kids, hands a-flash all the time, tirelessly weaving those precious nets. Yet this was not simply a woman’s task, this skill was essential for a trawlerman too. You’d best learn it well as you’d be making running repairs in the worst of conditions—cold, tired, and wet with waves breaking over the side and the deck constantly shifting underneath your feet.

As a little aside, at the end of our tour, Bob demonstrated the ‘braiding’ for us up on deck, using sisal yarn. Hard on the hands that is, but it’s the material the original nets would have been from. Even today he’s astonishingly fast and accurate. I tried to follow his weaving but didn’t stand a chance.

Figure 4: Bob Demonstrates Braiding a Net

© SharpieType301, 2022

Continuing in the Centre, the montages move you on seamlessly through the dockside and onto the ship herself. Once on board, it’s all set for a trip to the hazardous Arctic fishing grounds. You explore the radio room, hearing the shipping forecast and communications on the VHF marine radio.

Figure 5: The Radio Room

© SharpieType301, 2022

You pass through the wheelhouse, the skipper’s territory, and sacred ground this, with the ship’s wheel and compass, other navigation and electronic aids, the radar, ‘fish finder’ sounder and more. You visit the messroom, the foc’sle where you and your exhausted mates would congregate while off duty and try to snatch a few precious hours of sleep. You’ll experience a tiny taster of the dreaded top ice, albeit an extremely diluted version of the realities at sea, but still an unnerving glimpse into an alien world.

Figure 6: Breaking the Ice

© SharpieType301, 2022

You’ll see the all-important work taking place on the fish deck with a net of wriggling fish being lifted over the side. At the end of a trawl, the fish in the ‘cod end’ where they are captured, traditionally secured with a special easy release ‘cod knot’ in the ‘cod line’, are about to be released. All the while, gutting continues from the previous haul.

Then the final scenes, as you return home at the end of your two-week stint. Time to pick up your pay for a fortnight’s hard work and relish the solace of a pint at the Freeman’s Arms. Stepping out to the dockside, you can buy a present to take home for your nipper from the toyshop or treat yourself to a portion of freshly fried fish & chips. At those prices, Mr S simply couldn’t resist!

Figure 7: Fish & Chips Ashore

© SharpieType301, 2022

But back to the Ross Tiger’s tale. Skippered by George Edward Pedersen, she undertook her maiden voyage in early ‘57 and was the first of a fleet of ‘Cat’ class trawlers built for the family firm, the Ross Group (yes, that Ross—of frozen fish dinners fame, which many of us will have enjoyed at one time or another).

Ross commissioned the Tiger, first of their new, state of the art, ‘middle-deep water’ fishing fleet, at the peak of the UK fishing industry. This complemented their larger ‘deep water’ fleet (these were named for warships, and one of them, Ross Revenge, remains the last example of a ‘distant water’ side trawler and is the only continuing pirate radio ship in the world). This decision was planned to coincide with the 1956 Grimsby Fish Dock Centenary celebrations. This was the golden age of fishing when Grimsby was hailed as ‘The World’s Premier Fishing Port’ and ‘the Mecca of the World’s fish trade’. Amongst other things, this celebration also helped establish fish and chips as a British institution, but more of that later.

Tiger had acquired her fabulous feline name when, in keeping with the company’s commitment to Grimsby’s youth, children from a local school were asked to suggest names for the new fleet. This time the ships were not assigned names from warships, the ships were to be called after big cats (Ross also commissioned a fleet of smaller ‘near water’ vessels, to be named for birds). The kids had great fun, and came up with the names Tiger, Leopard, Jaguar, Panther, Cougar, Cheetah, Lynx, Puma, Genet, and Civet. However, there were twelve vessels in this class, and they couldn’t think of any more cats, which caused them a little upset. Thankfully, the directors at Ross Group were so impressed by their efforts that they waived their tight rules, meaning two of the ‘Cats’ took to sea named Ross Jackal, and Ross Zebra!

So, why is Tiger such a special lady? Well, for one thing she’s decidedly a classy lady, costing c.£85,000 to build in the ‘50s (about £6m today). For a working vessel, her internal specifications were nothing short of luxurious. She boasted central heating (a boon to ‘try’ to keep warm or dry soaked clothing), a state-of-the-art Galley with a sturdy double-oven Esse range for good hearty meals to be prepared.

Figure 8: The Ross Tiger’s Galley

© SharpieType301, 2022

There’s warm mahogany panelling with brass fittings throughout, a neat Mess Room with guarded tables so meals didn’t fly off the table, even flushing loos, a hipbath, and a shower. Such things were unprecedented to a crew more used to being soaked through for the entire trip, with a bucket to wash in if they bothered, and use of the ship’s rail for the call of nature!

Figure 9: The Mess Room

© SharpieType301, 2022

Despite this apparent opulence, her design was the very latest in stability and safety. She had a fully equipped lifeboat as well as recue pods, though in Arctic storms these may have been more a token than a practical option. Examples of the emergency drinking water tins and hard tack can be seen in the Skipper’s cabin. Ross took the crew’s safety seriously, actually producing a safety film in 1969 to promote safety at sea on fishing vessels.

This was sorely needed, as in the ten years of the 1950s, Grimsby alone had lost a staggering 32 ships. Indeed, commercial fishing remains the most dangerous industrial occupation in the UK, with an accident mortality rate 14 times that of coal mining. To put this into some form of perspective, as recently as 2017, every year one in just over two hundred fishermen died or was seriously injured in British waters.

Vessel Safety Inspector Nigel Blazeby, who chairs the Safety and Training Committee for The National Federation of Fishermen’s Organisations, and works with the Seafarers’ Charity to raise safety standards and practices explains why:

“The sea is a dangerous place. The way fishing vessels operate is the exact opposite to the way most ships work. Most ships load their cargoes in port, secure their hatches, people go down below deck and they go out to sea. Fishing vessels do the opposite. They come out of port and go to the middle of the ocean and the fishermen open the hatches and come out on deck. It’s like working in a heavy industrial factory with chains and cranes but you’ve got a moving floor so the chance of being struck by moving gear is much higher.”

Accidents, some of them life changing, were viewed as ‘normal’, but trawling is around 115 times more dangerous than an average industrial occupation. It’s a brutal and uncompromising way to earn a living—only serving soldiers in wartime have a more dangerous occupation.

When you left port, you didn’t know if you were going to come back. Gales and storm force winds can be encountered at any time of year, generating massive, sometimes freak, waves. In the icy waters where the cod and other valuable fish stocks feed, anyone unfortunate to be washed overboard has a minimal chance of survival—if not drowning likely succumbing to hypothermia within a very short period due to a lack of protective clothing and the intensely low temperatures.

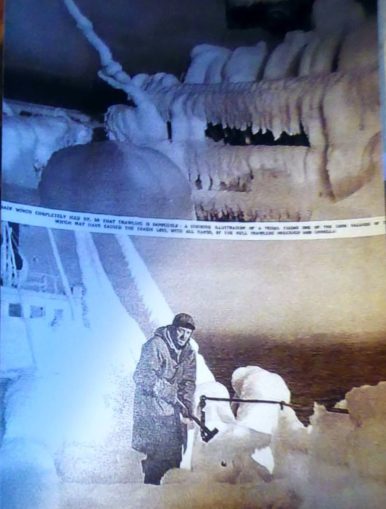

In winter months, and in the summer months at some of the colder fishing grounds, sub-zero temperatures quickly lead to extreme icing of the whole superstructure. The ‘top ice’ could rapidly make a normally stable ship top-heavy, liable to turn turtle and capsize. With limited crew space, each and every man aboard was responsible for breaking the ice from the affected surfaces. No simple task this, as photographs from the Skipper’s cabin show.

Figure 10: Extreme Icing

© SharpieType301, 2022

Furthermore, ship owners could be hard taskmasters, and the ships’ Skippers were expected to overcome difficult conditions to bring home the catch, whatever the weather. It was always the Skipper’s call about how bad the weather had to get before it was too dangerous, for the ship and his crew, to continue fishing. The crews relied on the profits from the catch to pay them for their hard-earned toil. If they were not catching fish, they’d have no income.

Working typically two-week trips, with just three days on shore before they set off again, theirs was a hard life. Every day, they dealt with the threats of a life at sea: hard and hazardous physical labour on windswept, exposed decks, harsh and unforgiving weather, anti-social hours with little chance to rest, no guarantee of a stable income, and long periods away from their families.

The men worked 18-hour days or more, stretching over waist-high bulwarks in rolling seas without safety lines, gutting up to 2 tons of fish from a single trawl.

The song ‘The Grimsby Lads’ from the RX Shantymen, written by John Conolly and Bill Meek, born and raised within a short distance of Grimsby Docks explains better than I ever could: https://soundcloud.com/rxshantymen/the-grimsby-lads

Another captivating portrayal of a trawlerman’s life can be gleaned by reading first-hand accounts in the Grimsby Telegraph. Under the ‘News’ link, their website has a Nostalgia section with, amongst other insights, a series of fishing tales from ex-deep water fisherman Michael Sparkes.

It wasn’t all hard graft though, as the Skipper had a sealed ‘Duty Free’ cupboard in his cabin with treats for those rare times when the crew could take a break.

Figure 11: ‘Duty Free’

© SharpieType301, 2022

Also, if a good catch was brought ashore, the trawlermen would have plenty of cash in their pockets and just three days to spend it before heading back to sea. This meant they were known locally as ‘three-day millionaires’, easily recognised in the 1950s by their pale grey or blue suits with pleat-backed jackets, baggy trousers and open-necked shirts. Even in the harshest depths of winter, Grimsby town couldn’t be as cold as a trawler off the Icelandic coast!

The newly designed ‘Cat’ class ships at least offered a ‘whaleback’, essentially a covered area at the forward end of the fish deck to provide a modicum of shelter for working and for emergencies. There was otherwise no shelter on deck—not an easy environment to work in when you consider the seas in which she fished.

As to the Tiger, for all that life has thrown her way, this 355-ton ship has shown serious staying power. The earliest diesel side-trawler of her kind left in the UK, she was built as a double-sided trawler, allowing the crew to fish from both the Port and Starboard sides. Around 131-feet long, with a 26-foot beam, she had a fish-room capacity of 8,500 cubic feet, close to a whopping 200 tons of fish—that’s a lot of fish suppers!

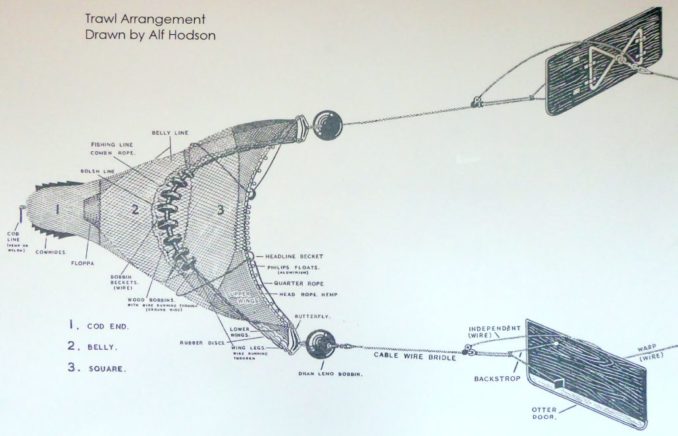

Driven by a seven-cylinder 7VG BXM 780HP marine diesel engine, by Ruston & Hornsby of Lincoln, she was powerfully built and could reach 11 knots, though she trawled at considerably slower speeds. Designed for bottom trawling, ‘otter trawling’ where large rectangular ‘otter’ boards were used to keep the mouth of the trawl net open. She dragged her net close to the seabed a full half a mile astern.

This arrangement is best explained by the Trawl Arrangement diagram below, drawn by the late Alf ‘Old Alf’ Hodson, a tutor at the Grimsby Nautical College for many years. ‘Old Alf’ was an accomplished artist, painting beautifully detailed watercolours, often portraying Grimsby trawlers, fishing boats, and deep-sea fishing vessels.

Figure 12: Trawl Arrangement

© SharpieType301, 2022

This type of trawl is designed to capture the demersal fish, such as cod, coley, hake, haddock, pollock, flounders, halibut, sole and plaice, in the narrow ‘cod end’ of a tapered trawl net. The demersal species include both benthic fish (which can rest on the seabed), and benthopelagic fish (neutrally buoyant fish that can float at depth with minimal effort just above the seabed). 17th century artist Jan van Kessel the elder’s painting shows a selection of benthic and benthopelagic fish laid out on shore.

Figure 13: Benthic and Benthopelagic fish

Image from Wikipedia, Public Domain

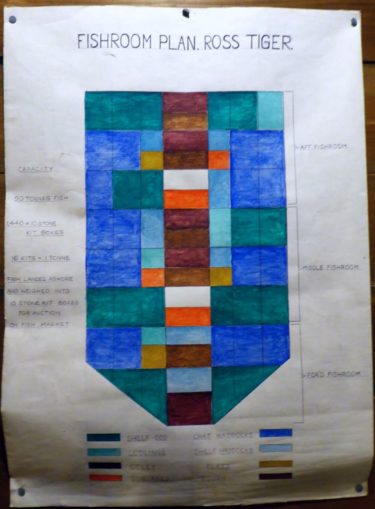

Tiger’s catch was inevitably a mixed one, with a number of different species of fish being netted. Once hauled on board, the fish would be gutted, sorted by size, then stacked down below in the fish rooms, separated into distinct storage areas by species. The fish were stored by arranging them in layers, with ice and planks between them to keep them fresh and in good condition.

A plan would be drawn up so the catch could be unloaded quickly and effectively once in port, all by hand, by men called ‘lumpers’ while the 15-man crew grabbed some brief but well-deserved shore leave.

Figure 14: The Fish-room Plan

© SharpieType301, 2022

The ‘lumpers’ acquired their name because they had to constantly dodge out of the way of heavy wicker baskets full of fish, which would swing back and forth as they were lifted from the trawlers. If they didn’t dodge quickly enough, they took their lumps! Across the Humber to the north, these men were known a ‘bobbers’ for similar reasons.

Unloading the fish from the trawlers was no easy job, and the lumpers were a hardy bunch. Indeed, a local brewery, Docks Beers, of Grimsby, has immortalised the lumpers on one of their core brews. Their 4.7% Stout Porter, ‘Elbow Grease’, is so named after the work ethic of dock workers past and present. It’s said that the men of the fishing industry actually inspired stout and porter beers, as they chose the dark, robust, malt-rich beers to fortify themselves for their labours.

Figure 15: The Lumpers

© SharpieType301, 2022

Teams of the lumpers worked together onboard the trawler, in cramped conditions, to load the cold, slippery fish from their stacks into baskets. These were then swung up and out of the fish rooms onto the dockside. Others caught the baskets full of fish and tipped them into fish ‘kits’, large aluminium boxes. A single filled kit would contain around ten stone, over 60 kilos, of fish, and on a good run Tiger could catch enough fish to fill 2,000 kits.

Common throughout the trawler fleets, was collecting the fishes valuable livers which, put into separate baskets, were reserved for manufacturing cod liver oil. Did you know that the supplement we buy as ‘cod liver oil’, rich in Vitamins A and D and Omega-3 fatty acids, isn’t just made with cod livers? It actually derives from the livers of a variety of species of ray-finned bottom-dwelling fish in the family Gadidae.

The Tiger served nearly thirty years in the fishing industry principally working the North Sea, Faroe Isles and Norwegian coast with a 15-man crew. That said, such was the quality of her construction, that she was able to venture beyond these waters to fish further north into the arctic during the summer months, when crew numbers increased slightly. British vessels had a long, proud history of fishing in waters far from our shores.

However, after the destruction wreaked on our fishing industry following the ‘Cod Wars’, in mid-1984 Tiger landed her last-ever catch at Grimsby. These disputes between Britain and Iceland through the ‘50s to ‘70s were over the right to fish in Icelandic waters (despite British vessels fishing in Icelandic waters since the 14th century). The impact on the town was immense as trawlers supported a large number of land-based occupations. Around eight people were sustained on shore for every trawlerman at sea, and thousands of jobs supporting the fishing industry with near one in five of the local population being dependent, whether directly or indirectly, on the fishing fleets.

Defiant though, our Tiger persisted. Once converted, with her trawling gear ripped out, she spent a further seven years as an OSV (an ‘offshore’ or ‘oil-rig’ support vessel) for Cam Shipping, transporting personnel, goods, tools, and equipment, to and from offshore oil platforms. This provided steady employment for ex-trawlermen on the newly converted ships, for a time. Sadly, the oil companies soon began to experience their own problems so, for this reason and also because of Tiger’s age, the company opted to de-commission her in 1991.

But still she endured, and in 1992, was re-acquired for Grimsby by the council for the princely sum of just £1.00, to embark on her current career. Now a floating museum exhibit, she is permanently berthed alongside the Grimsby Fishing Heritage Centre. She is a unique survivor of a now virtually extinct breed of vessels that once made up the largest fishing fleet in the world and acts to educate as well as interest people in the history of this important industry.

The Grimsby Fishing Heritage Centre’s website offers the chance to explore the Ross Tiger, with their interactive 3D walk through, allowing you to hear sound clips, more images, and videos, to get a good feel for the Tiger and life aboard. Link: http://bit.ly/rosstiger

The ship is also reputed to be haunted, as is the Centre itself. It has been said that staff, and some customers, have heard shuffling feet, or doors banging with no obvious origin. Some report unexplained cold spots, the smell of tobacco smoke, or aromas from food wafting from the Ross Tiger’s galley, unused in nearly thirty years. It is possible that this could be down to overactive imaginations, or the wind (and the East Coast can be a very windy place) carrying distant sounds and smells. It could, perhaps, be down to something else entirely—I’ll leave you to judge for yourselves, but for those of you who are curious, the ‘Are You Haunted’ team have visited Ross Tiger (see Season 2, Episode 5: ‘Total creep out’ on YouTube).

Back now to those fish, more specifically to the type served with chips. Can there be anything more British than a fish & chip supper?

Seafood, including fish and shellfish, has long been a popular food source. Indeed, there’s evidence of shellfish, finny fish and marine mammals being eaten as long ago as the Middle Stone Age, between approximately 300,000 to 30,000 years ago. By the 2nd century A.D., texts from Latin and Greek writers confirms that trawling was in common use, as the Romans often sea-fished using nets dragged behind their vessels. Since the 16th century, fishing vessels have been able to cross oceans, fishing the deeper, offshore waters in pursuit of fish. More recently still, larger vessels and the ability to process the catch on board means fish has become a more accessible food source.

Figure 16: The Fishmonger’s Stall (Adriaen van Utrecht, 1640)

Image from Wikipedia, Public Domain

The demersal species the trawlers sought: cod, coley, hake, haddock, pollock, flounders, halibut, sole and plaice, have been eaten with great delight for a long time. Sometime around the 1630s, the oldest Jewish community in Britain, Western Sephardic Jews who had fled persecution in Portugal and Spain, settled in England. The claim to remain here was unofficially legitimised in 1656, when Oliver Cromwell made plain that the ban on Jewish settlement in England and Wales was not to be upheld. They had brought with them a taste for fried fish, cooked in a similar way to ‘Pescado frito’, as their traditional Shabbat fish dish. This was made by coating the fish (usually a white fish, like cod) in flour, then deep-frying it in olive oil. It was simply sprinkled with salt as a seasoning, cooked on Friday, eaten cold on Saturday.

Figure 17: ‘Pescado frito’

© franzconde, licensed under CC BY 2.0

At end of the 18th century, former US president, Thomas Jefferson wrote about eating “fried fish in the Jewish fashion” after a visit to London. And in 1837, Charles Dickens’ Oliver Twist (a novel based in London) refers to a ‘fried fish warehouse’, where bread or baked potatoes were served alongside the fish. However, this was still a long way from the iconic dish that Britain is known for around the world. Where were the chips?

In truth, they are not a British invention. Potatoes originally come from Peru and other parts of Latin America. Cooking potatoes in fat over a fire is a practice they’ve used for thousands of years. However, when potatoes were ‘discovered’ and brought back to Europe by Spanish conquistadors in the 16th century, they were primarily used as pig feed. People distrusted a strange plant that grew underground and, fearing it was poisonous, soon named it ‘the devil’s apple’.

But, by the 1750s, potatoes had become a staple crop in northern Europe, with famines in the 1770s contributing to its acceptance. When the River Meuse froze over during harsh winters of the 17th century, preventing the people from obtaining seafood, resourceful women fried potatoes to replace the temporarily unavailable fish. When the Belgian Huguenots fled persecution, many moved to London and brought their potato-frying expertise with them.

By the 1800s acceptance was growing. In 1802, Thomas Jefferson’s White House chef, Honoré Julien, served ‘potatoes served in the French manner’ (deep-fried while raw, in small cuttings) at a state dinner. By the 1830s, fried potatoes were firmly in place as a staple food among the poorer citizens of London, and Dickens was, in a manner of speaking, in at the beginning of chips in Britain. In ‘A Tale of two Cities’, published in 1859, he speaks of “Husky chips of potatoes, fried with some reluctant drops of oil”.

Both Belgium and France declare they have a prior claim regarding the origins of chips, or ‘fries’, though as we’ve seen, the Belgian origin perhaps seems most likely. This view is strengthened as in 1748 the French Parliament had actually banned cultivation of potatoes, being convinced that not only were they poisonous, but that potatoes caused leprosy!

Bringing both the fried fish and fried potatoes together for sale as ‘fish & chips’ in Britain is first known from the 1860s. Whether this took place first in Lancashire or London can still be debated. From a wooden hut on the market in Mossley, Lancashire, John Lees is known to have sold both fried fish and chips in 1863. However, around the same time in London, a Jewish immigrant called Joseph Malin opened a fish and chip shop in Cleveland Way, in Bethnal Green. The dates vary for this shop and claims for both 1860 and 1865 have been made.

Whatever their true origins, this new culinary pairing rapidly became a great success. Since it was cheap, it was originally considered a food for the lower classes, but it tasted good, so it caught on. The spread was helped by the Industrial Revolution. The development of steam-powered trawlers led to plentiful supplies of white fish from the North Sea. The railway network connecting ports with towns and cities across the country made fish more accessible and affordable for heavily populated areas with their hungry multitude of workers.

Selling inexpensive, nutritious, and filling hot food, fish and chips shops began popping up all over the country, to begin with some just small family businesses operated from the ‘front room’ of the house. But by 1910, there were something like 25,000 chippies across Britain. At its zenith, in 1927, the number of chip shops had risen to more than 35,000.

Figure 18: Fish and Chips

© LearningLark, licensed under CC BY 2.0

Could fish and chips have helped win the World Wars? A tongue in cheek question, perhaps, but Lloyd George’s First World War Cabinet certainly acknowledged their importance and made sure the components stayed off ration. Feeding munitions workers, forces on leave and their families alike. Kept similarly off ration during World War II, Prime Minister Winston Churchill referred to fish and chips as ‘Good Companions’, a comforting way to keep morale high during a time of great stress, whilst providing valuable protein, fibre, iron and vitamins. Maybe there is some truth there.

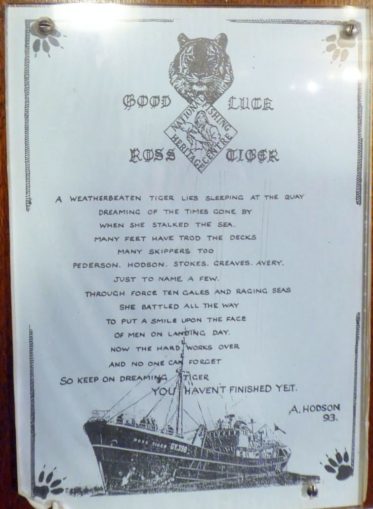

But none of this would have been possible without ships like the Ross Tiger, the brave trawlermen who crewed them, and the dockers who supported them. I’ll leave you with a few words from former Skipper and latterly Senior Tour Guide on the Ross Tiger, Alf Hodson (son of ‘Old Alf’), a man who passion and pride shine through the words of the poem he wrote for his ship.

Figure 19: Ode to the Ross Tiger

© SharpieType301, 2022

© SharpieType301 2022