There are pleasures even the most adventurous of lives can deny a gentleman. Despite the tales of derring-do from his previous life more interesting (occasionally mildly exaggerated), there are places your author has rarely visited and things he’s never done. An eclectic list, it includes never having smoked a cigarette or been fishing. I haven’t been tempted and know nothing about tobacco or riverbanks other than they sound like bad habits ruinous to the constitution and best avoided.

Therefore, a shiver ran down the spine as I turned the next page of our hundred-year-old mystery posh family’s mystery photo album. Before me, resplendent in his waterproofs, with net and rod in either hand and a tab hanging mockingly between the lips, was a figure that would push Captains Ahab and Birdseye into second and third places in a Mr Fisherman competition.

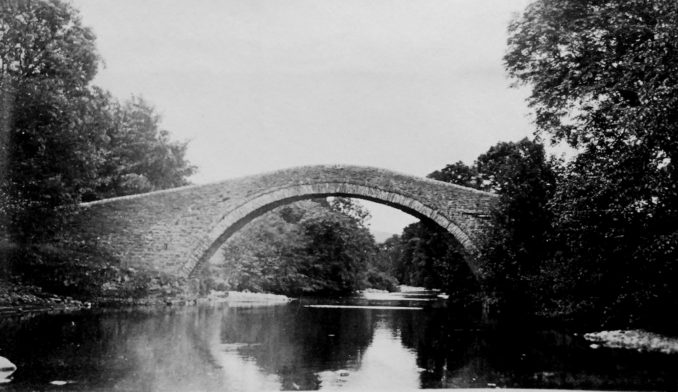

One’s mind immediately leapt salmon-like to the North of Scotland, to the Dee and the Tay. There were distinctive river crossings pictured amongst the photos. Was that the Bridge of Orchy? No, it wasn’t, abutments were missing. As I set off north of the border looking at bridges one at a time, something addled at the back of my mind. The photographs are a century old. Would the landscape be covered in forestry? Or even submerged behind the rural district council’s water subcommittee’s dry stone dam? Bad enough, but there was a worse nag.

Previously on Mystery Album, we visited the Stockton to Darlington Railway centenary, and then the Norfolk Broads. An East of England theme was developing.

While at the Broads, I revealed this author suffers a nose bleed south of Penrith, and vertigo on any flatlands bordering any sea. Likewise, when he begins the drop at the far end of that stoney moor and spies road signs pointing the unwary to alien places like Barnard Castle and Bowes, your author develops a fever and persistent cough. That demonic patch of tarmac at Scotch Corner always tempts a full 360-degree turn and flight back from whence I came.

But I am obliged to research what I see as I peer at Mystery Album’s sepia images through my railway modelling magnifying glass. That cascade of rocks looks like Alston but isn’t. A worked valley could have been Nenthead or Killhope but wasn’t. I need wiki and the excellent Mr Jonathan Neville of Norfolk Mills to tell me what a wherry is but I can spot two-hundred-year-old lead workings at 10,000 yards. A bend in a river looked like Gilsland but wasn’t.

There’s a reason things appear the way they do. The Amazon looks like the Amazon because it’s in the Amazon. The Nile looks like the Nile because it’s in the Nile. Likewise, if it looks like the North Pennines, flows like the North Pennines and has been mined like the North Pennines then it must be the North Pennines. And if I don’t recognise it, that’s because it is on the eastern side. Gulp.

I mustered all my courage and set off bridge spotting along the North and South Tynes and the River Tees – with no luck. I assumed Puffins would have to help with the heavy lifting, and said so in a previous instalment, but then the photos, as if comets above William the Conqueror at Hastings, began to align in my favour.

A bridge is a bridge is a bridge. No, it’s not. Like faces, railways engines and Norfolk Boards wherries they are all the same but all different. Fortunately, railway engines have numbers and names on them. Even our mystery family’s wherry had ‘Palace’ painted on its aft. The steamers at the mouth of the River Yar have coloured funnels and YH painted on their bow. Although not as specific, bridges usefully fall into categories. But first, there were some photos of a car.

As well as fishing and smoking I know nothing of fashion. Having said that, not sure about the hats, more enthusiastic about the number plate. That looks like an ‘H’.

Likewise, that can’t be anything other than an ‘N’. There will be a Puffin out there who knows everything there is to know about HN3388 down to the last rivet. I tip my hat to him and invite him to leave an enlightening unread comment below the line. As with fishing boats, car registrations are locational. Back in the day, HN meant Darlington.

My search headed south to Swaledale. I looked for a particular type of bridge – humped with a semi-circular arch of rubble voussoirs, surmounted by smaller stones forming a hoodmould. Oh, and with segmental coping leading to the parapets.[1]

And there it was, at Ivelet, up the valley from Richmond and the A1, thirty miles from Darlington along the B6270 which presumably was a rough track ten decades ago.

After that discovery, many of the other photographs fell into place.

Another river crossing turned out to be the footbridge at Muker. Returning to the car photo, the full picture shows a distinctive building behind. The notice above the door reads ‘Mary Shaw licenced to sell wine and spirits, ale porter and tobacco to be consumed on or off the premises’.

The roundel is of the National Cyclists Union. Around the rim it states ‘Official Quarters – National Cyclists Union’ and in the middle, ‘NCU’. In 1882 the NCU was formed by the merger of the Bicycle Union and the Tricycle Association. They were the sworn enemy of the British Cycling Federation.

The NCU produced publications to help cyclists, erected helpful roadside warning signs, banned cycle racing on open roads, banned professionalism and was a big enough organisation to require numerous regional quarters. A number of secret societies were formed in order to thwart the NCU and hold bike races. In order to appear not to be racing, cyclists would compete individually across timed sections in dark clothing and with no racing numbers. Maybe the world hasn’t only recently gone mad after all?

It wasn’t difficult to find Mary Shaw’s premises. It being a Grade 2 listed building, it is largely unchanged and is the Kings Arms at Gunnerside. Presently a community pub, it was used for a fishing holiday by our mystery family. In modern-day Gunnerside there is a Mary Shaw’s cafe opposite the Kings Arms and just before Gunnerside Gill. I wonder if she was a local ‘character’? On the outside of the modern-day Mary Shaw’s cafe hang shovels and peat cutters hinting at what lies on the moors above.

As for the round item at the top left-hand corner of the licencing sign, I’d say that’s a telephone connection. I may be wrong, my case relies upon a wooden pole visible opposite on modern-day Street View.

Down in the valley lie irregular four-sided fields, defined by dry stone walls, each containing a cow house. Farmed the Viking way, the cattle are placed inside in stalls for the winter. Complete with muck and water troughs at each end of the beasts, hay is piled up at the other end of the building for forage. The name Gunnerside is said to be Norse, from Gunnar and sætr meaning Gunner’s hill or pasture.

A look up the neighbouring Gunnerside Gill (‘gill’ being from the Old Norse word ‘gil’) shows the flow of moor water has cut into the hillside and placed nature’s gifts close to sweat and profit.

Pictured is Bunton mine at the upper reaches of the gill. At the top of the left-hand side of the light coloured tailings that have been extracted from the level, we can see a mine ‘shop’ dotted with four dark doors or windows. On the right-hand side, just beyond the tailings, the keen eye can make out a large wheel. This will have sat in a trough. A flow through the trough will have powered the wheel to crush and sieve the lead-containing ores from the level.

More recent photographs show that the tailings appear to be undisturbed. This isn’t always the case.

As well as lead, the extractions contained other heavy metals – in those days thought of as waste. Since then, some of these dumps have been worth re-working. For instance at Dufton Fell Mine on the author’s side of the Pennines. ‘Fell’ being from the Old Norse ‘fjall’.

Incidentally, when I took the family to Norway, a local wanted to know who’d taught us Norwegian. Our pronunciation was odd, our grammar, awry. At times he could barely understand what we were saying. We hadn’t been speaking Norwegian, we were talking amongst ourselves in our own dialect.

As for what’s nearer the River Swale, we learn a lot from little details in the background.

Even this townie can see that’s not a drystone wall but a pile of rubble. Dear me.

As for the grazing, is the farmer husbanding sheep or moles? Even the most squeamish know that moles belong hanging from barbed wire by their tails not undermining the river bank with their tunnels. What kind of a scruffy Herbert of a hayseed (with his pants held up with twine) holds this land?

Find out next week and be prepared for more surprises from the Mystery Album.

[1]Historic England, Ivelet Bridge.

© Always Worth Saying 2021

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file

Audio Player