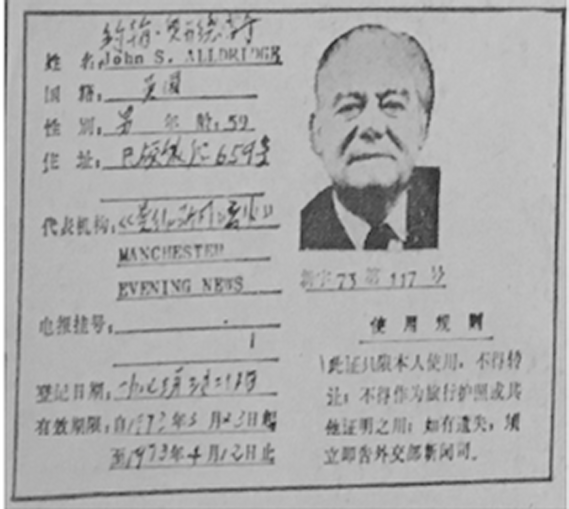

My uncle was a staff reporter for the Manchester Evening News from the late 1940s until his death in 1973. The following is from a series of articles in which he describes his extensive visit to China in 1973 and provides a fascinating insight into what life was like in China 50 years ago. It is reproduced with kind permission of the Manchester Evening News.

My uncle was a staff reporter for the Manchester Evening News from the late 1940s until his death in 1973. The following is from a series of articles in which he describes his extensive visit to China in 1973 and provides a fascinating insight into what life was like in China 50 years ago. It is reproduced with kind permission of the Manchester Evening News.

In this report John Alldridge visits one of the most important shopping streets in Pekin and finds that below street level the staff of the shops have constructed an underground maze of passages to be used in case of air raids. They did the work in their own time and without any pay.

Underground city

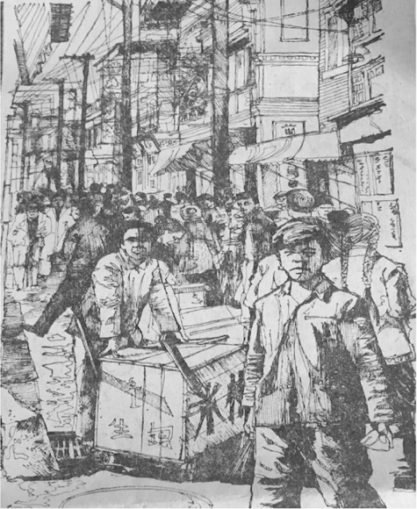

Dashan Lan Street is the Regent Street, the Rue de la Paix, of Pekin; though apart from its importance as a shopping centre, it bears little resemblance to either. So narrow that even bicycle traffic is barred from it, it cuts clean through the densely crowded commercial district of the city. A dusty, raucous bazaar of a street that boasts it can sell you anything from a pin to an elephant if you can find room to squeeze yourself through one of its hundred tiny shop doors. Any time of the shopping day – and an average Pekin shopping day is from eight in the morning until eight at night six days a week – you will find a steady flood of anything up to 10,000 customers flowing up and down Dashan Lan Street.

At the entrance to it there is a bicycle park and there we were met by the street’s chief air raid warden, a tall muscular giant of a man in a khaki uniform and ski cap that fitted him where it touched and a voice like a frustrated bull that marked him out as a regular sergeant-major in any man’s Army.

He shook my hand in a grip that threatened to fracture every bone in it while the crowd of curious bystanders, all wearing the same baggy blue boiler suits, clapped politely; a spontaneous welcome that by now was becoming a little monotonous.

Cutting a wedge for us through the crowd like an impatient bulldozer, he led us to a small tailor’s shop. We followed him inside and watched him surprisingly disappear behind the counter. A moment or two later be reappeared, smiling all over his broad, flat face. And – surprise, surprise – the floor behind the counter had mysteriously slid away. There instead was the top of a flight of stone steps leading down into the cellar below. At least, I thought it was the cellar. Until I found myself going down, and down, and down, like Alice down the rabbit hole.

When I reached the bottom, that was only the beginning. For the cellar had turned into a tunnel; a brick-lined, concrete-arched rabbit-hole of a tunnel, dimly lit by tiny electric lamps, that turned and twisted for almost a mile with galleries leading off it in all directions, and the cold air seeping down until my feet felt like ice.

We passed tiny antechambers that showed they were lavatories and washrooms and unfinished sections where gangs of workmen obediently dropped tools and clapped as we passed by. On and on we went and narrower and narrower that rabbit hole became. Until a very tall man or a very fat one couldn’t have made it. And I began to think of the catacombs in Rome and the maze at Hampton Court and wondered frantically what would happen if the lights went out and we were lost down there for ever.

Then the light suddenly grew stronger and the air blew colder and we were climbing up another set of stairs and so into a large chamber barely furnished with a long table, a dozen chairs round it, a blackboard with a map tacked to it that looked like a section of the Bakerloo line, and a row of empty shelves lining the walls.

And there was the entire executive committee of the Dashan Lan Street civil defence unit waiting to greet us. Waiting to greet us with the inevitable tins of cigarettes and mugs of hot, scented, sugarless tea, constantly refilled, that has become part of a ritual. There was another exchange of welcome, more polite hand-clapping. And then the Sergeant-Major, obviously anxious to get on with it, turned the proceedings over to Comrade Wa.

Comrade Wa, an almond-eyed, rosy-cheeked lass of 18 with the sauciest pig-tails, who by day they told me, worked as a shop assistant in the children’s store, went into action. She picked up a pointer and strode to the map, pigtails swinging aggressively now, like a tank commander about to brief her crew before the Big Attack.

We were at that moment, she told us, sitting 24ft below Dashan Lan Street. We were in the heart of the Street’s air raid shelter. It was 270 metres long, running from east to west, 11 metres wide at its widest, telescoping to six metres at its narrowest. It ran the whole length under the street, and tunnel entrances led up to the department store, the cinema and the drug store above. Escape lanes fed out into a secondary tunnel system through which shelterers could be led to safety a distance of two miles away.

In the event of sudden enemy air attack – which enemy she refused to specify – 12,000 people could get under cover here in between five and six minutes.

Although the shelter was not yet completed, it already had its own radio, telephone system, lavatories, kitchen, and a small first-aid centre.

And then came the biggest surprise of that surprising morning. All the work had been done, she told us, by the shop-keepers and staff themselves. Working every night after work, sometimes with very primitive tools, they had turned themselves into engineers and masons and bricklayers. And when there were no bricks, they made their own kilns and baked them.

It was as if, to get the thing in its right proportion, all the shop assistants and buyers and floorwalkers and boards of directors of Lewis’s and Pauldens and Marks and Spencer had suddenly got together by mutual consent and worked night after night – without pay – to build themselves an air raid shelter under Market Street, Manchester.

It seemed impossible – looking at the professional quality of that work – that this incredible tunnel could have been built by amateurs, no matter how dedicated. Yet what has been done in Dashan Lan Street has been repeated all over Pekin. In a city of more than four million people voluntary work teams have built air raid shelters under factories, schools, shops, apartment blocks. Some factories even have underground workshops already buried deep into the shelters so that work could continue even during an air attack.

These individual shelters are planned eventually to link up with Pekin’s half-finished underground railway. Then it is estimated that by 1978, 80 per cent of Pekin’s population could find shelter in the event of attack and Pekin itself would become a city underground.

Would this elaborate network of shelters really give the protection claimed for it? Even the experts themselves aren’t sure about that. I believe they see the tunnels as more effective for rapid dispersion of population rather than as permanent shelters.

But why this urgency to prepare against war at a time when China needs nothing so much as peace? Who are they afraid of? Ask that of Comrade Wa and she has the answer pat. “Chairman Mao tells us to dig tunnels deep, to store grain everywhere, to be vigilant, to safeguard our Motherland and never cease to be prepared.”

And what is good enough for Chairman Mao is quite good enough for Comrade Wa. And several hundred million other comrades like her.

Jerry F 2021

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file