Eleventh in a series by my uncle John Alldridge. This article first appeared in the Derby Evening Telegraph in January 1968 – Jerry F

I found him sitting beside me at a snack bar on the road to Billings. Or rather, he found me.

He was fat and fortyish and merry-eyed, and his chin hadn’t seen a razor for days.

He had a tongue as smooth as molasses and every word brought the Deep South ten miles nearer.

He carried a guitar with a built-in harmonica. And outside was the oldest Ford truck in the world.

Splashed across the canopy was the challenge, “Helena or Bust.”

He was enjoying a brief respite between recording, he informed me. Doing the rodeo circuit, just to keep his hand in.

Perhaps I had heard his latest recording? His own version of “Jailhouse Rock,” recalling a slight unpleasantness with the law in Miami.

Not yet in the Top Twenty, but moving up, my dear sir, definitely moving up.

I hadn’t heard it? Why, then, by a fortunate chance he had a copy right with him. Only a dollar.

Who wouldn’t give a dollar for a first impression that one day would be a collector’s piece? Oh, definitely…

I said, unfortunately, I wasn’t travelling with a record player. Then take it home, my dear sir. Enjoy it at your leisure. Savour it, like the aroma of a good cigar.

I parted with my dollar. He bowed like Barbirolli, and tucked the note away in a greasy notecase that had once been genuine crocodile.

He twanged his guitar in a gesture of gracious dismissal. When I left his merry eyes were already searching for his next victim…

He was my first experience of the rodeo circuit; that three-month summer jamboree that winds its riotous way through every cow town in the West, South-West and Canada, from Hobbs, New Mexico, to Moses Lake, Washington.

To the true Westerner, rodeo — pronounced ro-dee-oh throughout the West, except in California, where they insist on ro-day-oh — is the only sport that counts. The rest is sissy stuff.

It is a rough-and-ready sport that has come up the hard way. It started on the cow trails in the ’60’s and ’70’s and reached maturity on the ranches of Texas.

Today it is a big-money sport watched by millions.

Its great attraction seems to be that anyone can get into the act — provided he can ride and isn’t afraid of breaking every bone in his body.

It has its big stars, whose names — Dean Oliver, of Boise, Idaho; Winston Bruce, of Cochrane, Alberta; Ohm Young, of Albuquerque, New Mexico; Harley May, of Oakdale, California — are as well-known as “pop” singers.

But there are also thousands of “loners” — dedicated cowboys who ride or fly from rodeo to rodeo, ready to gamble a five-dollar entry fee on any event in which they think they have a sporting chance. Some of them take their wives or girlfriends with

them and live in trailers to cut down expenses.

But I imagine it’s no fun being a rodeo wife. Even if you have grown accustomed to your man being brought home on a stretcher at the end of the day, or paying out most of a season’s winnings in hospital bills.

For the rough-and-tumble of the rodeo the even chance of seeing blood is what draws the crowds.

Even in the bullring the odds are on the man. In the rodeo they favour the animal every time.

Usually there are five major events in every rodeo — saddle and bare-back riding, calf roping, Brahma bull riding, and steer wrestling.

Of these the star event — and the most dangerous — is riding the Brahma bull, and the bull-rider faces his greatest danger when he is thrown, for the bull is just as likely as not to go after him with vicious horns.

Bull riding at the Calgary Stampede,

Chuck Szmurlo – Licence CC BY-SA 3.0

This is where the cowboy clown earns his money. It is his job to lure the maddened bull, by whatever means he can, away from the rider long enough for the unseated cowboy to get over the fence and to safety.

The only equipment the bull-rider uses is a rope which goes around the bull’s middle. The rope has a hand-hold into which the rider puts his gloved hand and a helper pulls it tight.

When the rope feels tight enough the rider wraps the free end of the rope around his palm, clenches his fist as tight as he can, and hunches his body close to his hand.

Then when he feels the bull standing quietly under him he nods for the gate to be opened and away they go, bucking and kicking and rolling.

He must not touch the bull with his free hand, and at the end of eight seconds the judges score him on how well he rode and how hard the bull bucked.

But mighty few cowboys are able to stay on a rampaging, roaring Brahma bull for the full eight seconds.

A hand-hold on a surcingle is all the harness a cowboy is allowed to keep him on top of a bareback “bronc” for eight long action-packed seconds.

The rules require that he must have dulled spurs over the points of the horse’s shoulder when the bronco’s feet hit the ground on its first jump out of the chute.

His wild spurring is not showing off: it’s a rhythmical motion of his legs to keep the ringing from being torn out of his hands.

He keeps his seat close to his riding hand. As he turns his feet forward in time with the horse’s jumps, he knows the farther back he sits the more likely he is to be pitched off.

He hopes for a fast, high-jumping, twisting horse; for unless his mount is a hard bucker he won’t get high marks.

Contractors scouring the West for rodeo animals always look for the saltiest stock.

There will be some who buck harder, higher, longer without a saddle.

These are the broncs who lift the sensation-hungry crowd out of their seats.

“Saddle bronc” riding is one of the oldest of rodeo events and easily the most popular.

It is closely linked to ranchwork; and the cowboy who has had long years of experience with rough horses in the open is always up among the winners.

The instinctive reactions necessary to keep the stirrups, to sense what the horse will do and feel and time the rhythm — come from a practical tough schooling.

If he touches the animal or its equipment with his free hand or spurs, or loses a stirrup, or is bucked off before the eight seconds are up, he is disqualified.

Saddle bronc riding is not a contest between cowboys; it is a trial of man and horse.

Saddle bronc riding,

a4gpa from Provo, UT, USA, – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

Competitors are quick to tell each other all they have learned about a horse they have ridden, or tried to ride, so that the next man in may have a better chance of piling up some points.

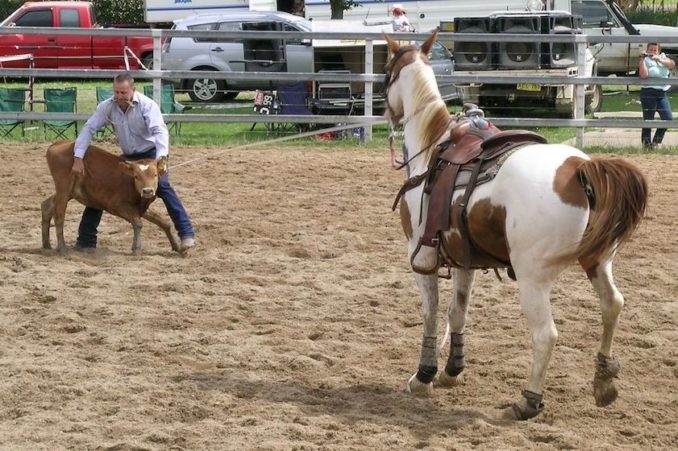

Probably the most truly scientific event to be seen in a rodeo is steer wrestling. It demands split-second coordination and perfect timing between the cowboy and his “hazer” and their horses.

Rodeo-steer wrestling,

Skarabeusz – Licence CC BY-SA 3.0

Cowboy and hazer team up to work together usually throughout a whole rodeo season.

Their horses must be well-trained to start and stop at exactly the right moment. The hazer gets one-eighth of the cowboy’s winnings.

The mounted cowboy waits at the gate, with the hazer posted on the opposite side of the ring, until the steer crosses the score-line. The hazer’s job then is to keep the steer running straight.

The cowboy leaps from his running horse to the horns of the steer, to halt it and wrestle it to the ground.

The steer must be on its feet when the wrestling begins. Running falls don’t count.

The wrestling horse sweeps on by. As he reaches for the steer the cowboy digs his heels into the ground to slow its speed. He reaches for the right horn tip, using his left hand for additional leverage under the steer’s jaw.

The steer is caught off-balance, its head upturned, and literally throws itself.

The winded steer must be flat on its back, all four legs extended, before the official time is given.

Steer wrestling, sometimes called bulldogging, was never part of ranch work. It has developed as the result of an act originated 40 years ago by a negro cowboy, Bill Pickett, in a Wild West show.

In calf-roping, rider and horse work together in a perfect rhythm which is beautiful to watch.

Calf roping at a rodeo,

Cgoodwin – Licence CC BY-SA 3.0

The horse is trained to stand quietly behind the barrier.

When the calf is released the horse must reach his peak stride in a jump or two; then stand stock-still at the proper distance behind the calf so that the roper has room to throw and hold his rope taut as he dismounts.

The rider then runs down the length of the rope, throws the calf, and ties two hind feet and one front foot with the tie rope he carries between his teeth.

Time counts from the moment the barrier drops until the rider throws up his hands to signal a “tie.”

The cowboy spends many hours training his horse to become a solid, true-working mount.

Any variation of the pattern in the ring means the loss of valuable points. Because of their natural speed and quick acceleration quarter-horses are preferred.

The cowboy who has such a horse can put a four-figure price on him, and the best horses are known and followed from rodeo to rodeo.

Rodeo cowboys, with few exceptions, come from ranch backgrounds, where riding and roping are part of everyday life.

But in the last 10 years a new breed of rough-rider has entered the professional ranks.

Through a staggering army of junior rodeos, national high-school and inter-college rodeo competitions these young newcomers are full of arena experience before they venture into the annual rodeo circuit.

They are given further opportunity to shape their skill through countless roping clubs and in-practice riding-arenas which have mushroomed over the country from coast to coast.

But, in the final analysis, the important thing is that you should love rodeo above all things.

To quote one veteran bronc rider:

“The mainmost thing about rodeoin’ — to be good at it — is you gotta like it more’n anything else. You jest fall natural into the swing of it, an it’s jus’ like dancin’ with a damn gir-rul.

“There’s some has got all it needs to rodeo — good build, tough, strong an’ all that — but they just don’t like it, an’ them’s the ones what don’t ever make it.”

NEXT: What happened to Custer?

Image © Reach PLC. Image created courtesy of The British Library Board

Jerry F 2023