This Is My England,

© 2022 Newspapers.com

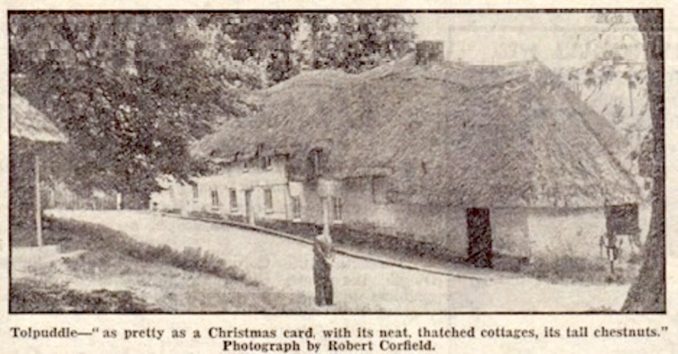

Look at Tolpuddle now, with its neat thatched cottages, its tall chestnuts in splendid flower, all in all as pretty an English village as ever found its way on to a Christmas card, and you will sense no echo of the abominable crime that was once committed here in the name of justice.

© Newspapers 2022, Going Postal

An English village — particularly a Dorset village — changes very little in a hundred years. And Tolpuddle must have looked very much like this (except, of course, that it was mid-winter and not spring) when six men of Dorset were torn from their homes, loaded with chains, and carried away to the farce of a trial at Dorchester, the verdict of which had already been reached before the judge had taken his seat.

The charge for which they were committed, tried, and sentenced to transportation for seven years seems fantastic today — that they did criminally administer an unlawful oath to one Edward Legg.

Yet when Judge Baron Williams delivered sentence hardly a voice in that crowded courtroom was raised in protest.

For if an Englishman could be sentenced to death for stealing a sheep why should he not be exiled to the ends of the earth because he and a few fellow-criminals conspired to have their wages raised from nine to ten shillings a week?

So far, at least, have we travelled along the path of human dignity in a hundred years.

Before the transport took him off to Australia — 14 weeks at sea, battened down under hatches like wild beasts most of the time — George Loveless, spokesman of the six, wrote a last letter to his wife in Tolpuddle.

I have seen a copy of that letter. And I quote from it because it is one of the most tender, touching letters I have ever read.

Remember, it was written by an English agricultural labourer of the nineteenth century — a member of what was then described as “the inarticulate mass of the working-class.” And written, moreover, by a man who knew that he had been unjustly punished and was about to be separated, perhaps forever, from everything he held most dear:

“Be satisfied, my dear Betsy, on my account. Depend upon it, it will work together for good, and we shall yet rejoice together. I hope you will pay particular attention to the morals and spiritual interest of the children. Don’t send me any money to distress yourself. I shall do well; for He who is Lord of the winds and the waves will be my support in life and death.

“You may safely rely upon it, I shall never forget the promise I made to you at the altar; and though we may part awhile, I shall consider myself under the same obligations as though living in your immediate presence.”

It is good to know that there was a happy ending to that tragic story: that “the inarticulate mass” did find its voice.

And found it so effectively that at long last George and the other Tolpuddle men were granted a free pardon.

But only one of them came back to Dorset to stay. The rest preferred to work out a new destiny in a new and freer world. And I, for one, can’t blame them.

There is a memorial now to those six from Tolpuddle. It takes the form of a row of pleasant stone cottages, each cottage named after one of the six. It is a thank-offering from the nine million British trades unionists, whose worldwide movement began under an oak tree here in Tolpuddle.

We found the great-granddaughter of George Loveless working in the little garden of the cottage which bears his name. A modern, labour-saving cottage that would have seemed like a palace to George and Betsy Loveless.

Home of George Loveless, Tolpuddle Martyr,

Bob Hopkin – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

I asked her if she remembered anything of her famous ancestor. She thought for a while, then shook her head. “It’s a long time ago now,” she said.

Perhaps it is.

We stayed that night at one of those country hotels where the only inhabitants seem to be pale, frail creatures enjoying a prolonged convalescence and elderly folk slowly dying of boredom.

The air was heavy with genteel complaints, which ranged from the size of the butter ration to the clicking of my typewriter.

I was glad to escape from that polite “Never-Never Land” and get out on the road to Plymouth, which has had a glorious past, is enjoying an eventful present, and is looking forward to an exciting future.

There is a large-scale map of Plymouth and its neighbour, Devonport, in the city’s museum. The caption is perhaps deliberately ironic — “Where the bombs fell.”

If I had filled a pepper pot with ink instead of pepper and shaken it vigorously I couldn’t have made a worse mess of that map.

There is hardly a street that isn’t marked with at least one ominous little black dot.

Even today, nearly ten years afterwards, the centre of Plymouth still looks as if it is just recovering from an earthquake.

One of the most devastating effects of the Plymouth blitz was that a couple of concentrated raids completely wiped out the city centre. The municipal offices, the Guildhall, the shopping area all disappeared.

So whether it liked it or not local government became decentralised. The town clerk, for instance, found himself billeted about two miles away from the city engineer. And it has remained that way ever since.

As a typical example, I found the staff of the city’s information office camping out in a gay little Nissen behind the fragment of a 16th-century church wall.

Perhaps this compulsory decentralisation is one of the reasons why the Herculean labour of reconstruction is going ahead more briskly here than almost anywhere else in Britain.

The moment you penetrate into the heart of the new Plymouth – which isn’t easy, because they have instituted a most formidable one-way system — you are made violently aware that something exciting is going on.

For one thing, the air is alive with the clang of hammers and the machine-gun bark of rivets going home.

You realise this more than any other time between 12 and one in the afternoon, when the huge labour force is having lunch and for the first time you can hear yourself speak.

And already they have something to show for it. Climb to the roof of one of the few remaining buildings and you can see the ground plan forming of the great north-south axis which will stab through the heart of the city.

One day that wide promenade will appear, in the words of the practical visionary who planned it, “as a garden vista: a parkway, with terraces, slopes, steps, and pools.”

There will be not a trace left of the hideous old muddle of narrow, tortuous streets which in the days before Hitler made travelling in Plymouth so exhausting.

The plan for a new Plymouth began while the bombs were still falling. But, as the planners quickly found when the time came to put theory into practice, it is one thing to plan a new city; quite another to get it built.

For this was not Russia — where it seems that whole populations can be moved from one end of a continent to the other with the stroke of a pen — but democratic England, which at times can be as obstinate and obstructive as a mule. And a good thing too.

In the beginning the corporation very wisely decided to buy outright the site for their new city centre. It cost them three million pounds.

To get some of their money back they offered selected sites to business firms who were prepared to build in accordance with the general design.

And there they ran into their first snag. Because, after all, a businessman who has got to foot the bill has his own ideas of what his premises ought to look like: and those ideas are not always going to agree with the ideas of the city officials, or, again, with those of the Reconstruction Committee, which has another set of ideas altogether.

As an official report puts it tactfully; “It has not been easy to reach conformity.” It has not been easy, either, to get the materials to do the job. For instance, Plymouth gets an allocation of about 750 tons of steel a month: it needs three times as much as that. But somehow the work goes on. The broad boulevards of Royal Parade and Armada Way (what a wealth of Plymouth history is in that name!) are in being.

And although as yet they have nothing on either side of them but a bomb-battered church they are already one of the widest carriageways in the whole West Country.

And, by a happy thought, at the point where they meet there is a tall flagpole. And the base of that flagpole has been moulded into the shape of Drake’s drum.

Having been compelled to live in one for a number of years in various parts of the world I never realised what a neat little architectural job a Nissen hut could be until I came to Plymouth.

For the time being the centre of Plymouth has been transformed into Nissentown: you see that ubiquitous semi-circle of corrugated iron everywhere attractively disguised as a block of offices or a row of shops.

We even had lunch in a green “blister” Nissen on Plymouth Hoe itself.

To commemorate the fact that we were sitting practically on the spot where Francis Drake played that famous game of bowls, students of the Munich School of Art have painted the scene in a large mural over one wall.

So we sat with our backs to Francis and our faces towards the sparkling waters of the Hoe with Drake’s Island dead ahead. And very pleasant the whole thing was.

Drake’s Island in Plymouth sound,

Robert Brimacombe – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

But this, after all, is only temporary. To see where the new Plymouth – the great dormitories – are already coming to life you have to drive a mile or two outside the old city to a bluebell wood, where a building contractor has set up his command post.

For there is a war going on here in Plymouth. In 1939 the population of Plymouth was 220,000. After two years of continuous “blitz” it had been reduced to 119,000.

One of the first bold decisions the planners made was that the old city could not afford to accommodate more than 180,000.

So right then in 1943, before the idea became the subject of national controversy, Plymouth began to plan its own system of “satellite” towns.

Weeks, months, years of ceaseless arguments have been hurled into the fight. But the war is almost won.

Already the trim new houses are crawling up the soft Devon hills. From that command post in the bluebell wood you can see them all clearly.

In a year or two 2,500 families will be living here in well-planned homes – homes the Tolpuddle Martyrs dreamed of perhaps, but never saw.

Reproduced with permission

© 2023 Newspapers.com

Jerry F 2023