A little confession first. This is a bit of a cheat ‘postcard’ because, although I have visited this lovely seaside town many times, I also lived there for a blissful year or so, overlooking Cardiff Bay and the docks before the Barrage was completed. However, it’s a great place to visit, not only for the sea and Victorian and Edwardian architecture which is still plentiful, but it’s a place with a long and fascinating history, so I’m going to give you the lowdown anyway.

Derived by Sharpie from OpenStreetMap! © OpenStreetMap contributors, with cartography licenced under CC BY-SA 2.0

I grew up in Cardiff and my first visits to Penarth were made as a small child, and that’s when I fell in love with it. Only about five miles away, the sticky-up bit of a headland just across Cardiff Bay is Penarth, an old-fashioned seaside resort. Now and again, if dad’s shifts fell right so he was back from the steelworks when the rest of us were home, he and mum would round us up, kids, dog and often my nan, stuff us into the Yellow Peril (a yellow Ford Prefect), and take us there to have a walk on the pier and a paddle, depending on the tide. I mention the tide because that stretch of the coast along the Severn Estuary has, at 15 metres between high and low water, the second largest tidal range in the world. Only the Bay of Fundy (Eastern Canada) experiences a greater range, and that’s only a metre more.

Penarth wasn’t my parents’ go-to seaside place, as the beach is a mix of rock, shingle and a bit of gritty sand. For a proper bucket and spade day on a sandy beach, we’d head off to Barry Island. But Penarth was close by, and for me, much as I liked Barry (especially the donkeys), it was a truly magical place. There was such a lot to attract a curious child.

One of my favourite things was to walk from the town (at the top of the hill) through the Edwardian delights of Alexandra Park down to the seafront, stopping to say hello to the numerous squirrels, the birds in the aviary and the fish in the ornamental pond, with its fountain splashing and sparkling in the sunlight. As you walk through the park, if the weather is clear, you can see right across the Bristol Channel to Somerset and Devon, with the islands of Flat Holm and Steep Holm in between. Some of you might be aware that the first ever wireless signals across open sea were transmitted, by Marconi, from Flat Holm to Lavernock (a little way along the coast from Penarth).

Derived by Sharpie from ‘Guglielmo Marconi’ © BiblioArchives/LibraryArchives, licensed under CC BY 2.0 and ‘Flat Holm and Steep Holm’ © Ray Ok, licensed under CC BY 3.0

The seafront is lovely, whatever the state of the tide or weather. Not without reason did the Victorians refer to Penarth as ‘The Garden by the Sea’. The Esplanade runs past the Victorian Pier with its intricate ironwork and the gorgeous Victorian building which once housed The Old Public Baths (filled with sea water in its heyday, much later turned into ‘The Inn at the Deep End’ pub). It continues towards the balconied Yacht Club and the new Lifeboat Station, passing the pretty Italian Gardens (designed as a rock garden) with its unusual palm trees, exotic plants and the wonderful Wishing Well, on the way.

The Italian Garden was home to another important attraction – the public loos. Imagine my surprise when, going back after years away, I saw, what award-winning restaurateurs described as a ‘beautifully restored Victorian beach pavilion’, was no longer a shrine to convenience but a rather pricey joint called The Fig Tree! But I digress…

If the tide was out then walking on the shore was possible. From the Lifeboat slipway, away from the Pier, you could sometimes find fossils, especially after a big storm. If you walked in the other direction, back underneath the Pier towards Cardiff, you could pick up lumps of pink alabaster from the beach below Penarth Head. The cliffs are mostly sandstone with veins of alabaster in various colours from red to grey-green, some pure white, and more naturally occurring pink alabaster than anywhere else in the world. Interestingly, there were alabaster workshops at Nottingham, where I now live, in the 14th and 15th centuries – I wonder if some of the material they worked with might have come from Penarth?

© Mary Gillham, licensed under CC BY 2.0

But the jewel in the crown for me was Penarth Pier. In the summer months, this inquisitive brat would lay on the slatted wooden decking for hours to watch small fish in the water swimming in and out of the fronds of seaweed sensuously swaying in the current, their holdfasts keeping them firmly attached to the cast iron pillars. On one of those long hot summer days, not only were there fish but hundreds of small jellyfish, almost see-through, each decorated with a four-leaf clover pattern of white rings. Years later, I found out that these were ‘moon jellyfish’ (Aurelia aurita).

© Σ64, licensed under CC BY 3.0

But that wasn’t the only attraction the Pier held for me. It still entices fishermen and women, though the latter are a bit scarce, to congregate at the furthest end from the shore hoping to catch something. Apparently you can land whiting, mullet, cod, bass, conger, pouting, and flounders from the Pier, but when my dad took me fishing there (always in winter), I caught the odd cold, a great deal of seaweed, at least one grumpy and disgruntled crab, and an old boot!

© SharpieType301 2006

The end of the Pier was also the landing point for a couple of wonderful vessels, the paddle steamer PS Waverley and MV Balmoral. These beauties sailed from Penarth Pier for decades, to another country – to exotic places like Ilfracombe and Minehead. A trip on the Waverley was very special, as you could go down into the engine room and watch the massive pistons driving the paddle wheels. The noise they made was tremendous. For one magical summer, there was a trial of a passenger-carrying hovercraft between Penarth and Weston-super-Mare. I didn’t get to ride on it, but do remember being told about it, probably by my brother who would have been a teenager then.

© David, licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

The Pier was home to another couple of treats too. At the entrance, just outside the turnstiles, there was an ice cream shop. But this wasn’t any old ice cream – this was Thayer’s – pure dairy ice cream, not a vanilla pod in sight! Then, in the winter, when the wind was howling and the waves were churning so ice cream wasn’t quite what was needed, there was a tea stall halfway along the Pier which sold hot drinks and freshly griddled Welsh cakes. Absolute heaven… if you could get out of the wind!

© Dave Snowden, licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

Other traditional seaside edibles could be found at Rabaiotti’s café, almost opposite the Pier. The food was too expensive for us as a rule (and, I’m reliably informed, not unerringly appetising), but I do remember a special treat. Mum took me and my sister to share a Knickerbocker Glory, with strict instructions to pass the long spoon back and forth nicely. Mind you, ‘twas her birthday so she got the glacé cherry at the bottom – I still haven’t forgiven her!

But back to Penarth – even its name bears a little controversy, being a combination of two Welsh words pen (head) and arth (bear), so the ‘Bear’s Head’. Although seemingly romantic, this makes some sense because as you travel southwards by water along the Welsh coastline of the Severn Estuary, the headland is the first area of high ground for a fair distance. Maybe the topography looked like a crouching bear to early travellers. But, modern ‘scholars’ had to go and spoil it by saying the name is probably condensed from Pen-y-garth, so pen (head) and garth (cliff), giving the rather more prosaic name ‘Head of the Cliff’.

Whatever its toponomy, the roots of Penarth are undisputed. Neolithic stone axe heads have been found in the town, and there’s evidence of human habitation dating back 5000 years, likely longer. It was certainly settled during the Bronze Age and Iron Age, and while I’ve found no clear evidence of Roman settlement it was known, and its resources exploited by the Romans. Penarth stone was used in the Roman fort in Cardiff.

In Mediaeval times (a.k.a. the Middle Ages), well after the Romans departed, the lands in and around Penarth were given to the Black Canons of St Augustine. From 1183 they fell under the purlieu of the Abbey of St. Augustine in Bristol (which is now Bristol Cathedral). This remained the case until the English Reformation in the mid-1500s when, along with many ecclesiastical institutions, the Abbey lands were appropriated by order of Henry VIII and its assets ‘redirected’ to the Crown as part of the Dissolution of the Monasteries.

The lovely church of St Augustine on the headland (just along the road from where I lived as an adult) was founded in the High Middle Ages, and although the Mediaeval churchyard cross remains the original church no longer exists. Though completed in 1242, the original church was demolished in 1865 to build a larger, much grander church with a 90-foot tower, a landmark still visible if you drive towards Cardiff along the M4 from the Severn Crossings. It is quite special, so is Grade I listed.

© Gareth James, licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

During the 18th century, whilst the original church still stood, Penarth and the coastline around developed a distinct reputation for illegal activities. However, these weren’t really new enterprises, as in the 1570s a Special Commission had been set up to investigate and suppress such lawlessness. Set between Flat Holm and Cardiff, the ‘centre of villainy’, all sorts of contraband (not least tea, wine, spirits and tobacco) was ‘imported’ through Penarth. This almost certainly needed the connivance of some of the less honest Cardiff Customs authorities, who were in league with the smugglers.

Tensions in Penarth, and Cardiff, increased in the mid-19th century as destitute Irish immigrants in great numbers flooded into the area to escape the poverty of the Great Famine (the Irish Potato Famine of 1845-1849). The differences in language, religion, culture, and politics made clashes inevitable, and one of the first ‘race riots’ took place in Cardiff in 1848, when a Welshman was stabbed to death by an Irishman. The sheer scale of the immigration problem in that year is highlighted by a report from the Manchester Guardian, referring to a single day when: ‘On Friday last more than 200 Irish paupers, men, women, and children, landed from Cork on Penarth beach, and instantly proceeded to demand relief at the Cardiff workhouse… ‘

Irish refugees couldn’t ‘officially’ disembark when they reached the Welsh coast. Unscrupulous skippers of the boats they had boarded were not licenced to carry passengers, who were treated as nothing more than convenient ballast to be dumped unceremoniously on Penarth’s beach. The Irish community in South Wales became known by the derogatory nickname ‘mud-crawlers’.

Smuggled goods, however, were handled more carefully. The old Penarth Head Inn, set at the head of a shingle beach, sheltered from prevailing winds, and within easy reach of Cardiff, was a perfect landing place. It was well known for involvement in this lucrative trade – Edward Edwards, the victualler whose home was the Inn, had founded a real smugglers’ haven! Sadly, it has not been possible to partake of a glass of ale at the Penarth Head Inn for many years. The more principled Customs men took their revenge in 1865, demolishing the Inn and building the impressive Edwardian Baroque ‘Custom House’ to cater for Penarth’s flourishing shipping trade, checking papers for goods entering or leaving the country and collecting taxes on traded goods.

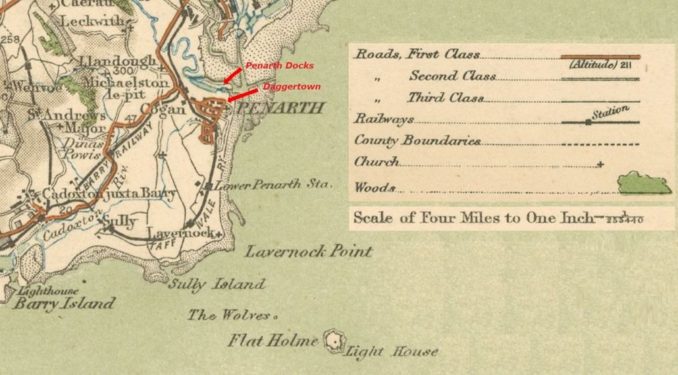

The massive expansion of the South Wales coalfields in the 19th century meant that Penarth developed rapidly from a small rural farming and fishing village to the town it is today. Close to Cardiff, the natural conduit for industrial materials from the South Wales Valleys, its sheltered spot behind the headland made it the perfect place to build Penarth Docks, and open the River Ely’s tidal harbour. From here, good Welsh coal could be shipped worldwide.

Instrumental in this were the interrelated, and often warring, Bute and Windsor families who effectively ‘merged’ in 1766 when Charlotte (heiress to the Windsor estate) married John (Lord Mountstuart, the eldest son of then Prime Minister, Lord Bute). Though small in relation to Cardiff, Newport and Barry, Penarth Docks (opened in 1865) proved cost-effective and very rewarding for its owners. In 1913, 4,660,648 tons of coal were shipped from Penarth Docks in just one year.

This image incorporates historical material provided by the Great Britain Historical GIS Project and the University of Portsmouth through their website A Vision of Britain through Time, licensed under CC BY 4.0

Efficient or no, the area around Penarth’s Windsor Road, between the still-disreputable Cogan and the headland, as well as the streets which led towards the docks soon became notorious. Daggertown, as it was known, along with the docks themselves were treacherous neighbourhoods, especially at night. The district was home to numerous pubs (some of which, like The Pilot and the Clive Arms, remain), together with a host of unlicensed drinking dens. Brothels, ‘baccy’, gambling, and opium dens were also common, and there was more than the occasional murder.

Despite the reputation of the dockside and its surrounds, in Victorian times Penarth town was already a popular holiday destination for folk from the Midlands and the West Country. Its heyday was the late Victorian period, and in 1878 the railway between the South Wales valleys and Penarth was completed which encouraged hundreds of day trippers from the valleys especially at weekends and holidays. Attractions included the beach, the Pier, the parks and bowling greens, the pretty Grade II listed Windsor Arcade, and the Turner House Gallery (also known as ‘The Sunday Gallery’). A little later two rather grand and ornate cinemas (one, now a coffee shop, with a classical ‘Art Deco’ frontage) meant there was plenty to see and do. The good times continued through to the early 20th century and the outbreak of the First World War.

It was thought that exports of Welsh coal through Penarth Dock would pick up again after the Armistice, and once Britain recovered from the effects of ‘the war to end all wars’. Sadly, that was not the case, and then a severe worldwide economic downturn (the 1930s Great Depression) hit. The coalfields of the South Wales Valleys were badly affected, and suffered massive unemployment and poverty. This meant that the coal trade and other exports through Penarth Dock dwindled, so in 1936 it closed. Although it was revived during World War II, its long-term operation was unsustainable, and the dock closed for good in 1963.

The Second World War wrought considerable changes to the entire town. Many of the decorative, traditional Victorian iron railings and balustrades were ripped out, and re-used to build tanks and aircraft. Some of them could have ended up at Grangetown’s Currans (a factory manufacturing munitions, where my mum and aunt worked for a while) or Cardiff’s Royal Ordnance Factory No.17, close to where I grew up. With its proximity to Cardiff’s docks and steelworks, and with St Augustine’s church a prominent landmark, Penarth became a natural target for German bombers, with air raids continuing from 1941 to the end of the war. The town had its own Dad’s Army (Home Guard), and members of the Yacht Club proudly volunteered to assist in the Dunkirk evacuation, sailing their yachts and motorboats across the English Channel to France.

In October 1943, the United States Navy established a base in the town, reopening Penarth Docks in preparation for Operation Overlord, D-Day and the Normandy landings. The US servicemen attended local dances, so ‘GI Brides’ were not uncommon! Many troops set out for the Normandy beaches from there, and this was commemorated in a painting of Penarth Docks in 1944, by Captain Arnold Winfield Chapin, the base commander, who presented it to “the people of Penarth“. Both he, and his wife, Camelia, are buried at Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia.

Some of the old docks are now a marina, with No. 1 dock and the outer basin dredged to accommodate several hundred yachts. There are a couple of boatyards there too. These are surrounded by a modern housing complex just behind a big Tesco, the Penarth Marina Village. While this sounds rather posh, being ‘waterside’ properties, I understand the area is co-habited by prolific rats.

A memorable visit in more recent times occurred in 1995, when I took my (future) husband to Penarth for the first time. It was a warm summer evening and, after we’d meandered down to the seafront from the town, the sun was beginning to set. Those public loos I mentioned earlier were still there. They were in the basement of the Victorian beach shelter, but there were stairways up to a flat roof terrace at either end. Up we went to lie and watch the sunset, then see the stars come out in a perfectly clear dark, moonless sky. It was quite magical.

© SharpieType301 2010

We moved to Penarth shortly afterwards and spent a very happy time in the top flat of an old house on the headland (yes, we lived in Daggertown!). The view was superb, and we looked straight across the bay to the entrance of Cardiff’s Queen Alexandra Dock, roughly along the line of the new Barrage which was still under construction. We watched from our kitchen window as the Royal Yacht Britannia pulled into the dock on her farewell voyage in 1997.

We were so sad to leave beautiful Penarth, but pastures and adventures new in Yorkshire called – tales for another day. Penarth didn’t want us to leave any more than we wished to leave her though. On moving day, our pig of a hired van (a big ugly Luton-bodied Transit in dark blue with rust highlights) made it halfway up the M6 on the way to Bradford, before the axle started whining and knocking. Slowing down helped a little, but we knew we wouldn’t manage the rest of the journey. RAC to the rescue, and after an awfully long delay we continued our move in sheer luxury… knackered, soggy, and jammed into the cab of a recovery vehicle. Once we had finally unloaded the van, we found that the rhythmic banging disappeared – we were just overloaded. Ooops!

© SharpieType301 2010

If you have never visited Penarth, it’s very well worth the trip. There is still a lot of the original architecture to be seen, and it’s a relaxed place. The Esplanade has smartened up (it even has a Michelin Starred Restaurant) and the Pier had a major revamp around ten years ago, including complete refurbishment of the Pier Pavilion. Oh, and that little stall on the Pier selling irresistible homemade Welsh cakes is still going strong. The local beer is first-rate, after all it’s only a hop, skip and a jump away from the Brains Brewery. That’s a reason for a visit all by itself – just don’t forget that the flagship ‘Brains SA’ is affectionately known as ‘Skull Attack’ for very good reason!

© Paul Burroughs, licensed under CC BY 2.0

© SharpieType301 2020

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file