There were three tasks involved in modernising and preserving the family archive, the second of which was to digitise the audio recordings. Digitising the old photographs was covered in a previous article, while digitising the family 8mm home movies will be covered in the third, and final article of this short series.

The old family photographs date back to about 1860, but the sound recordings only go back some 60 years or so, meaning all our audio material is on magnetic tape (developed in the late 1920s), so mercifully, no wax or tinfoil cylinders, or other media formed part of this job.

My family was lucky enough to own tape recorders from 1961 onwards, and we had a lot of fun with them. Over 20 years, we made dozens of family recordings, but the enthusiasm started to wear off in the mid-70s, and they were mostly used for recording professional music from records, or the radio, after that.

Much of the material we recorded over the years wouldn’t be of interest to outsiders, but nevertheless, I’ve included a few clips here, some of which I may have posted in the comments before.

We had a brief revival of interest in making tape recordings when the parents became grandparents, as it was deemed that some sort of audio record of new arrivals should be made.

Amongst the tapes are recordings of childhood readings, family games, home-made theatre performances, carol singing, piano lessons, musical performances and suchlike, plus recordings of family gatherings like birthday parties, Christmas parties, and so on.

Some material was recorded with the microphone in front of the TV – a recording of the first man landing on the moon being one of them.

The tape recorder sometimes became a feature of family parties, with everybody performing a party piece, and then listening to a replay, and discovering what their voice sounded like to other people. It was all great fun!

Amongst our collection of family-interest-only tapes, we have a recording of The Old Man and myself telling an uncle about the fun to be had with a tape recorder, and the value of recordings to (family) posterity.

He was quite impressed after he listened to recordings we made at a family event he was attending at the time, and uncle did buy a tape recorder after that, and I know his children still have the recordings he made at a number of family events, and at other times.

Sadly my cousins no longer have a tape recorder to play their tapes on, so I’ve been trying to get my hands on their tapes to digitise them for some years, but with no luck as yet.

I know their recordings include some of myself and little bruv behaving very badly at family dos, and of Dad leading Christmas/Easter sing-songs with his ukulele – with myself and little brother doing everything we could to put him off. I’d love to hear those tapes, if only for the embarrassment factor.

Although I was fortunate to have been born into a comfortably off, middle-class family (Dad was a civil serpent in the days when civil servants believed in service, not self service), we weren’t that well off, so couldn’t afford to buy new tapes every time something we felt was worth recording came along, so it was normal practice to record over tapes that already had stuff on them.

This meant that over the years, a lot of good stuff was quite simply lost. But on the other hand, my cataloguing task ended up being shorter than it might otherwise have been. Having said that, little snippets of earlier recordings do remain in the gaps between later recordings.

Some tapes did have stuff on them that was marked to be kept for posterity, and NOT to be erased or recorded over.

I was particularly keen to preserve the recordings of my very early efforts at playing in bands, but my little brother thought otherwise, and recorded pop tunes off the radio over most of my precious early band recordings. A crime he’s never been allowed to forget.

No recordings of my very first secondary school band remain, but there are tapes of the second, and later line-ups of our school band. I have recordings of our versions of tunes by bands like Small Faces, Status Quo, The Herd, The Equals, The Rolling Stones, The Troggs, Beatles, Cream and suchlike.

The Hardware

Our First Tape Recorder – Stella Stellaphone ST 454

Acquired in 1961, our Stella was an Austrian-made tape recorder, which really was a Philips EL3541 tape recorder in disguise. It was a single speed (3¾ ips – inches per second) quarter-track (four track) mono recorder, which came with a crystal microphone. It was actually a very good machine, and the cost new was £38-17-00.

(Note: the tapes used on home-user tape recorders were normally ¼ inch wide, and four tracks could be recorded on them, with 2 tracks on each side of the tape. This meant you could get four mono recordings onto a single tape, or two if you were recording in stereo).

It served us well, and we captured some good recordings with it, until it became somewhat redundant when we bought a stereo recorder in 1970.

The Stella was still in working order when it went to the tip as I cleared out the parents’ house in 2001. The manual went into the paper re-cycling bin quite recently.

Unfortunately I have now found out that both tape recorder and manual are worth decent amounts of money today, as vintage audio equipment is very much in fashion at the moment.

Tape Recorder #2 – Unknown Manufacturer and Model

As we’d been having so much fun with the Stella tape recorder, a few years later I asked if I could have my own tape recorder, and duly received one for my birthday. It was a small, cheap, battery-operated tape recorder from Woolworths.

I mostly used it for recording my schoolboy pop groups, although as it was portable, I do recall other exploits with it, such as recording echoing noises down a new drainage pipe that was being laid near our house. This involved setting the tape recorder up at one end of the pipe, and wailing and shouting ‘hello’ etc, down the pipe from the other end.

Tape Recorder #3 – Akai 4000D Stereo 2-Speed

After getting good use out of the Stella, the family decided (or, more accurately, I persuaded Dad), that we needed to upgrade our recording capabilities to stereo. I’d probably been badgering him about it for months.

In November 1970, Dad and I visited Tottenham Court Road to check out the tape recorders in all the hi-fi shops. (This particular London street was a haven for hi-fi fans and electronics geeks in those days – with shop after shop full of electronic gadgets and hi-fi equipment).

It was almost certainly me, rather than Dad, who’d decided what make and model of tape recorder we should end up with. The Old Man probably just agreed with whatever I said – after all, it was us kids who knew most about stereo, hi-fi and electronics back then – the older generation still lived in the world of wind-up clockwork gramophones.

The grand-parents’ old HMV wind-up gramophone was given to us when I was really, really young. The shellac 78rpm records revolved at an alarmingly fast speed, and you just knew they would have sliced your head off, Goldfinger-style, if they’d launched themselves off the turntable and ‘headed’ in your direction.

But to be fair, in the Old Man’s defence, he was a very early radio-adopter, and made Cat’s Whisker radios when he was a boy, inspired by Mr. Marconi, whose New Street Works factory was located just a few miles up the road in Chelmsford.

Radio, and ‘wi-fi’ in particular, just seem to get bigger and bigger, and it’s all down to that inventive Italian immigrant. Dad was born 6 years after Marconi arrived in England, and was 10 when the Chelmsford factory opened.

Father had to endure demonstrations of quite a few different makes and models of tape recorder in a number of Tottenham Court Road showrooms that day, and of course the one I really wanted was ‘out of our price range’.

After I’d worn him out by going up and down the street double-checking the prices in all the shops, we went for the Akai tape recorder pictured below – an Akai 4000D. It was the second model in their 4000 series of recorders, and went on to achieve near-legendary status around the world as an entry-level consumer tape recorder.

We paid £89.95 for it, which, let’s face it, was quite a lot of money in those days. A Revox recorder at around double that price would have been nice, but never mind.

We struggled home with it on the tube, all boxed up. It’s a very heavy machine, weighing over 25lbs, or 11.5kg in metric language.

I found something ‘wrong’ with it when we got it home – too much tape hiss, which my Dad’s elderly ears couldn’t pick up as well as my teenage ones could, so I took it back, exchanged it, and carried another example home.

I took the second one back for an exchange too, and third time lucky, the one we ended up with is still working pretty well 55 years later.

70s – 80s Japanese electronics actually have an excellent reputation, and many examples of their equipment from that era are built like tanks. Sadly though, a number of the great Japanese brand names have been bought up (by China, for example), and the stuff produced under those names today quite simply isn’t in the same class.

Recently, I was pleasantly shocked to discover the kind of money vintage audio equipment like our Akai sells for on the secondary market these days. Our particular model can sell for £200-£300, which isn’t bad considering what we paid for it. How many other low-mid range products appreciate in value over the years, and hold that value for a decent amount of time?

Our tape recorder may not have been a Nagra, Ferrograph, Revox, or Nakamichi, but the Akai still looks like it was a good investment – although long-term value was the last thing on our minds when we bought it.

The warm sound typical of analogue audio machines (but not the background hiss and mains hum that’s integral to analogue tape recorder recordings), is coming back into vogue – just like vinyl records, as is the equipment needed to play them.

Our Akai machine never had a service, or even had the heads demagnetised, as far as I know, (although the machine does sport a built-in demagnetising circuit), so by the time I started using it again recently it really was in need of a little bit of TLC.

As I started my latest, and hopefully final adventure with the old tapes, the Akai’s motor became intermittently squeaky, and then the machine developed a problem on playback with peaks crossing over from one track to the other, and then the sound began cutting out completely during the loudest passages.

I really thought the dear old device was about to expire, but undaunted, I found an electronics engineer who could service the machine, so drove the 100 miles to his home and handed it over for a full service. He did a very good job.

Tape Recorder #4 – Pioneer CTW-850R Twin Cassette

Purchased in 1992, this deck was connected to the computer to digitise all the cassettes, most of which were recordings of my old amateur folk rock band. I haven’t bothered digitising any of the old shop bought music cassettes, or home-made mix tapes. Yet.

Tape Recorder #5 – Panasonic RN-106 Dictaphone Microcassette Recorder

This small device was used to deliver the content of a few microcassettes to the computer for digitisation.

Cataloguing The Tapes

The first stage in the digitisation process was to go through all the old tapes, headphones on, to find out and catalogue what was actually on them. Although each tape was already accompanied by a half decent old list, with index numbers against each audio segment indicating the start and finish points, they simply weren’t adequate for the task ahead.

Index numbering varies from tape machine to tape machine, and a segment of tape played on one machine will have different index numbers when played on another. These numbers definitely don’t correspond to minutes and seconds.

This indexation process turned out to be very time consuming, as I noted down the start and end points, and content of each audio segment.

However, when there were two mono recordings on the same side of a tape, I saved a bit of time by listening to both recordings simultaneously, one in one ear, the other in the other ear.

I did this work back in 2003 while we had an agonising 6 month wait for our house purchase to complete. Burying my ears in old tapes was as good a way as any I could think of for passing time during those frustrating months.

Next I copied all the family stuff from the tape recorder onto my Apple computer, which had all the high-end multimedia accoutrements back then that are standard on computers these days.

Those rough, first digitisations of the recordings only received minimal editing, and no sound ‘cleaning’, but did benefit from neat fades at start and finish.

My tape digitisation skills have improved since 2003, and I’m well stuck into another, and final go at the tapes using the latest technology and software. It’s so easy to remove rumble, hiss, wow and flutter and assorted noises on recordings with the latest computer software.

Curiosity about what gems of personal family value might be embedded on those ageing reels of ferric oxide and celluloid tape is a good motivator, and keeps me ploughing onwards.

Besides the family material, there were a couple of dozen tapes of music recorded from records and the radio, containing nothing I thought was of interest.

Having got a bit fed up with the job by that point, these tapes were binned unceremoniously, but joyously – something I rather regret now, as a lot of obscure but interesting 60s and 70s rock recordings ended up gone!

One of the disadvantages of the family-recordings-only cataloguing policy was that anything that wasn’t ‘family’ was catalogued as ‘scrap’, and thus of no interest.

I recently accidentally played back some of the ‘scrap’, only to find I had a complete recording of one of the very first episodes of University Challenge, and an almost complete recording of a second programme from series one.

None of the video tapes of the first few series of this TV programme have apparently survived, so I digitised my ‘rare’ audio recordings, added a few photos, and loaded them onto YouTube, where they have accumulated over eight thousand views, and counting.

Magnetic tape begins to degrade after 10–20 years, but overall, our reel-to-reel tapes have lasted well, now being up to 65 years old – Philips, Emitape, Realistic, BASF and EM Scotch. A couple of low quality tapes have stretched a bit – but fortunately nothing significant on them has been lost.

The more recent cassette tapes have all survived in very good order – these are mostly TDK, with a handful of Maxell. There were also a couple of Memorex cassettes, which haven’t lasted quite so well.

Eventually the rather tedious and time consuming task of cataloguing the contents of 35 tapes came to an end.

Outsourcing To Experts

I own the equipment needed to record every one of the tapes onto the computer, with the exception of one four track reel-to-reel tape, and two minicassettes, so these were sent to a professional digitisation company.

When I got the minicassettes back, I was a little disappointed to discover there was only about 2 minutes of content on them.

As for the four track tape, the company messed up, and while one track of four was correctly recorded separately onto its own digital track, the other three were all combined on a second track, leaving tracks 3 and 4 blank.

The point of the exercise was of course to get the four tape tracks onto four separate digital tracks. They got it right second time.

The Software

To record, then clean up and edit the old recordings on the computer, I used a software programme called Audacity. I can’t speak too highly of it.

It’s a free, open-source digital recording and audio editor application, available for Windows, macOS, Linux, and other Unix-like operating systems.

First available to the public in 2000, and downloaded over 300 million times since, it’s able to record audio from multiple sources (including the ability to directly record audio playing on a computer), and boasts a wealth of effects for post-processing audio:

trimming, normalization, fading in and out, to name just a few

It has excellent noise reduction capabilities, enabling the worst of the mains hum and tape hiss that plague recordings made on lower-end analogue equipment to be removed. Find a split second of tape hiss, rumble etc., somewhere on the recording, on its own, with no other sound, then use the effect to analyse that noise, and then remove it from as little or as much of the track as desired. Magic!

There is a facility to automatically remove silent gaps in recordings, and files can be imported and exported in a number of formats, with the WAV format probably being the most popular – I exported all my newly restored files in this uncompressed format.

(Note: uncompressed means an audio file with the content stored in its raw, original form – in other words, every aspect of the original recording is preserved. This does, however, mean that file sizes are much larger than compressed format alternatives).

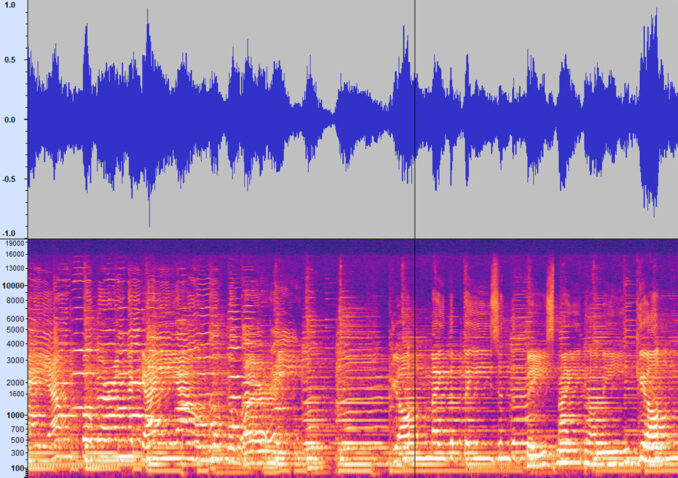

Other restoration tasks can be a bit more time-consuming, and may require editing the sound ‘visually’.

Fortunately, the software offers good visual analysis of audio in terms of waveform and spectrogram displays, and once you understand exactly what you’re looking at, such displays are extremely useful when it comes to removing pops and clicks, and other extraneous sounds that can spoil your recordings – a cough, a motorbike passing outside, or a chirping bird, for example.

Conversely you can boost mumbled bits of conversation, and other audio elements of a recording on a frequency by frequency basis, rather than by simply amplifying a whole snippet of a track across the whole frequency range.

Distortion caused by levels being set too high at the time of the original recording cannot usually be removed – only ameliorated, and sometimes in the worst cases must simply be deleted, and a patch of similar nature from somewhere else in the recording dropped in to fill the gap.

When restoration has been completed, the limiter and compressor effects can be used to even out volume levels by reducing loud peaks and boosting quiet sections, and the whole track can then be normalised for export. This effect sets the volume, or peak amplitude of a track, to the optimum level.

While it’s a great programme, it should be considered to be an audio recorder and editor, and not a DAW (digital audio workstation).

There are plenty of alternatives to Audacity, some of which are available in free versions. Examples include Descript, GarageBand, Reaper, Logic Pro X, Pro Tools (Basic Version £8 per month to rent or £79 per annum), Adobe Audition (£30 a month to rent, or £238 per annum).

Nevertheless, Audacity has more than enough functionality to satisfy any enthusiastic amateur audio engineer – all the tools required for editing, repairing recordings, and exporting the final result to whatever audio format is required or preferred.

Connections

It’s not too difficult to work out how to connect your source hardware to the computer, and, if necessary, to purchase suitable cables with the correct plugs at each end.

I connected the Akai to my Windows PC using a cable with twin phono plugs at the tape recorder end, and a standard 3.5mm stereo jack plug at the other, which I plugged into the blue “line-in” or “auxiliary input” on the computer.

However this ‘standard’ connection configuration had problems. The computer was overloaded by the signal strength from the tape recorder. The first test recording was drenched with distortion, and there were multiple signal cut outs.

Fortunately there was an alternative output on the tape recorder – a 5-pin DIN socket, which I was able to connect to the computer using a rather unsatisfactory two-cable arrangement consisting of a DIN plug to phono plugs, and phono sockets to 3.5mm stereo jack plug.

If I wanted to record a mono track on the computer, I had to disconnect the phono plug for whichever track of the pair wasn’t being used. This was an on your knees, under the desk type job, and as well as making recording easier, it also minimised crossover interference from one track to its neighbour, if only in my imagination.

Digitising The Original Tape Recordings

Once everything was connected up, I was ready to press play on the tape machine, and record on the computer.

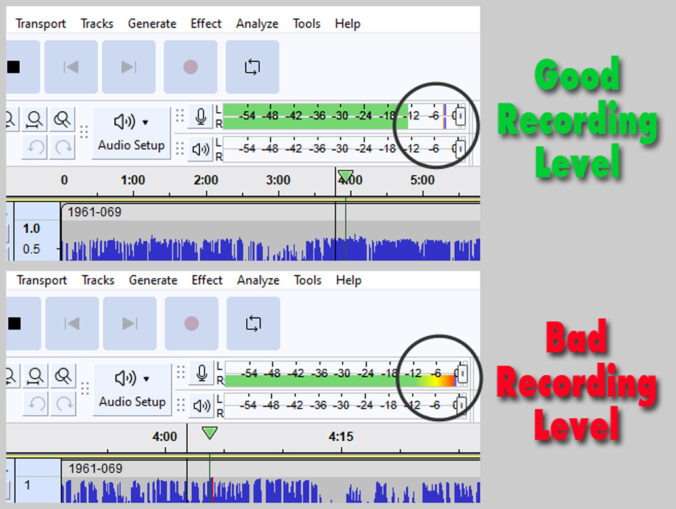

The aim here is to record the material onto the computer at the optimum level. You need to find the loudest part of the audio segment you wish to record, and set recording levels relative to that. It’s generally considered advisable for the peaks of a recording to not exceed the -6dB level.

In the image below, the vertical line in the top recording meter shows the loudest level reached has just exceeded the -6dB level, which is perfectly acceptable, whereas in the lower recording meter, levels have hit or exceeded maximum, which is something to be avoided.

Once you have captured the audio to your satisfaction, you can edit and tidy the recording.

Simply trimming the ends of the recording, and applying very short fades may be adequate, or you could edit and clean up the recording using the facilities already described.

The file can be exported once the overall volume level has been set to the optimum. While some sources suggest a peak amplitude of 0dB (the maximum level allowed), I prefer to leave a little headroom, so normally go for -0.25 or -0.5dB.

The Results

Restoring an old recording can take a long time – a pastime in the true sense of the word – a job for someone with a lot of patience, something I’m fortunate to have been endowed with. For me, it’s all well worth the effort.

And what did I find on the tapes?

Mercifully there were almost no incidences of gormless voices saying ‘Testing 1-2-3-4’, because tape time was always precious, but the Old Man did sometimes cough to set recording levels just before starting a recording.

Our earliest recordings from 1961 include my little brother reading, age 7; the Old Man playing his banjo and ukulele; the whole family singing round the piano; family friends visiting the day before the Old Man had a heart attack, and his return home from hospital a couple of months later; plus a recording of little brother and myself opening our Christmas presents at 6am on Christmas morning in our bedroom.

There is actually quite a lot of family music and singing on the tapes, and lots of boring stuff – recordings of piano lessons (mercifully just the one), for example. Most of the material wouldn’t be of interest to people who don’t know our family.

As the years passed, we got more adventurous with our tape recordings. I had great fun making recordings. Examples include:

An unaccompanied attempt to sing the Fireball XL5 theme song, followed by an appalling effort at playing the tune off the top of my head on the piano.

A one person spoof version of Sunday Night at the London Palladium.

A solo carol service, which began with an explanation that I would be singing all the carols on my own because the rest of the choir hadn’t turned up (a joke that appealed to my 9-yr old’s sense of humour).

Other ‘adventurous’ recordings include my Old Man’s outside recordings of the various choirs he was involved with – often recorded in churches.

These recordings include the Board of Trade Choir performing secular songs in 1964; the local church choir performing songs and madrigals; and a very impressive performance of Bach’s St. Matthew Passion with The North London Sinfonia, performed on Good Friday 1974, which I well remember attending, and being very impressed by. Maybe some of those recordings will make it onto YouTube one day.

To recap: load the ageing and increasingly fragile tapes onto a tape recorder; get the source material into the computer; strip out noises, clicks and pops, plus feedback, distortion and clipping (over recorded, and thus crackly tiny segments); tidy up the ends by adding a bit of silence and some fades; and get the final export levels right. The process is pretty straightforward once you’re familiar with it, if a little tedious and repetitive.

Here are a few examples of some of the material on our tapes, which have been embellished with photos from the family archive. The University Challenge video has images mainly sourced from elsewhere.

My maternal grandmother sings her party piece at a family Christmas party in 1961. This risqué song was written by Cecil Mack and Albert Von Tilzer in 1904. (01:41)

My mother reads Good and Bad Children – in a voice from an England now long gone. It’s also a good example of conserving tape time, as Mum only delivered 3 out of the 5 verses of this Robert Louis Stevenson poem, with the two, darker, final verses added here using rolling text. (00:48)

One of my father’s banjo recordings, recorded in his bedroom, and illustrated with some old family photos. (01:02)

My most adventurous attempt to combine family photos with an audio recording to date. It’s my university rock band recorded in 1973 at one of our jam sessions. (09:14)

A great find buried amongst loads of other stuff on our old tapes, previously categorised as a ‘scrap’ recording. Featuring the show’s original quiz-master, Bamber Gascoigne, it’s now the most popular video on my YouTube channel, with nearly 7000 views. (24:00)

See also:

Text & Images © 2025 NeverUpToTheJob