In August 1951, as preparations for the 1953 Everest Expedition were underway, my uncle John Alldridge wrote about the previous expeditions for the Manchester Evening News – Jerry F

“I guess my real reason for finally yielding my eyes to the great mountain above was that by now it was the only summit above me – the others had gradually sunk beneath the mounting altitude of the little fighter plane.

“Now even Everest was slowly giving way, and I headed directly for that mass of reddish yellow rock, all of it covered with ice and snow except where the everlasting winds of the upper air had torn the covering away.

“At 30,000 feet and just south of the centre pyramid I saw the ‘plume’ of Everest, formed by snow being blown from the summit. On this day it pointed to the south, borne by a north wind, and the sun shining through it made a rainbow that was beautiful.”

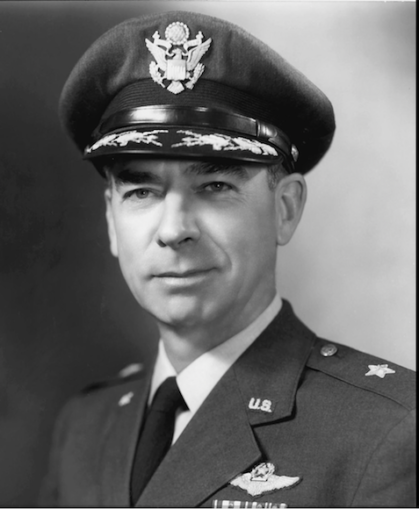

The man who wrote that – an American airman, Colonel Robert L Scott, Jr – had looked down on something which for 50 years a handful of men at the prime of their manhood, trained to the last inch, have struggled in vain to reach – the roof of the world, the highest ascertained point on the surface of the globe, Chamolang, the Sacred One – Everest.

BRIGADIER GENERAL ROBERT L. SCOTT JR,

United States Air Force – Public domain

There have been seven expeditions to Everest: in 1921,22,24, in 1933,35,36, and the last in 1938. Two of them – in 1921 and 1935 – were simply reconnaissance parties. But all were British – sponsored by the Mount Everest Committee, which in turn is composed of members representing the Alpine Club of London and the Royal Geographical Society.

In addition there have been a few plane flights over and around the peak and one abortive and suicidal attempt by a lone English climber.

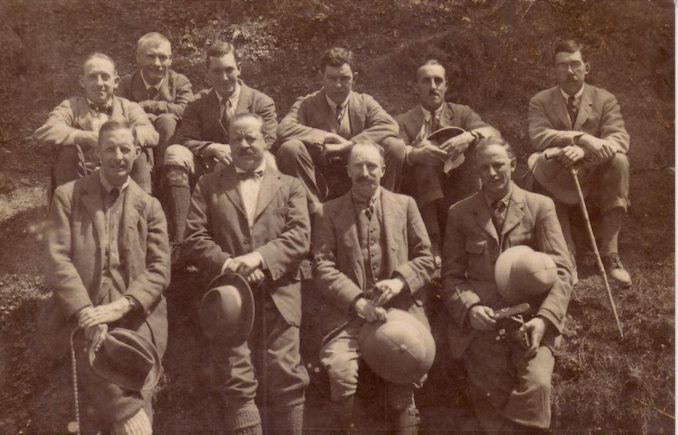

Historically, and in terms of accomplishment, the 1922 expedition – the first full-scale attempt to reach the top – was the most successful. Composed of ten Englishmen and a large team of Tibetan and Indian helpers, it first pioneered the long trail across unknown country to the base of the mountain.

From there after three months of intensive surveying and reconnaissance the first picture of Everest in close-up was obtained.

They discovered that the southern face of the mountain was almost certainly unclimbable.

The northern and western sides seemed little better. Only in the north-east did there seem to be a chink in the armour. By skirting the 10,000ft. precipice which was the north face and by climbing a steep ridge sweeping down from a great rocky shoulder near the summit it was just possible, they believed, to reach a high snow-saddle on the east of the Rongbuk glacier.

This saddle, they decided, might be the key to Everest, and so far every attempt on the mountain has been made by way of this saddle, called by the Tibetans Chang La and by all “Everesters” the north col.

Led by George Leigh-Mallory, whose family have lived for generations in the Cheshire village of Mobberley, where he was born in 1886, three members of the 1921 party got as far as the col itself. They were then only 6,000 feet from the top and only two and a half miles away.

Then they had to return. But they had succeeded in their mission. They, and the world, knew now that Everest could be climbed.

The next year a party led by Brigadier-General Charles Bruce, a veteran of the British Army in India, established a string of camps on the Rongbuk and East Rongbuk glaciers, and sent two teams to a height of 27,000 feet-2,000 feet short of the target but at least half a mile higher than man had ever climbed before.

The 1922 Everest expedition team at Darjeeling,

Unknown photographer – Public domain

On their way back they were overwhelmed by that kind of casual unexpected tragedy so common on Everest. They were caught by an avalanche that swept away seven native porters. The 1924 climb got even higher. But like its predecessor it was crowned by tragedy. In the early afternoon of June 8 George Leigh-Mallory and his young companion, A. C. Irvine, set out on the last painful struggle to the top.

George Mallory in 1924,

Alexander Wollaston – Public domain

Andrew Irvine,

Christina Livingston – Public domain

They had less than 2,000 feet to go, N. E. Odell, the expedition’s geologist, who had seen them leave, looked up anxiously through a clearing in the mist to see summit, ridge, and final peak of Everest unveiled, and high above him a “tiny black spot” silhouetted on a snow-crest.

The black spot moved, and then another speck of life in that wilderness of snow and ice appeared, moving upwards to join the first on the crest.

Towards a rock step, almost at the base of the final pyramid, they crawled, and then the vision vanished, veiled in mist.

Did they reach the top? No-one knows. Colonel Norton, then leader of the expedition, believes they did. Other authorities, including the last man to see them, agree with him. One thing is certain: they reached a height of 28,227 feet – less than 800 feet from the top.

“We expect no mercy from Everest,” Mallory had written in a last prophetic message. She showed them none. . . .

It was nine years before another expedition could be mounted for the assault. The 1933 expedition was the largest and most elaborate yet assembled. Its

members were most of them still in their twenties and early thirties, but included Frank Smythe, Eric Shipton, Wyn Harris, L R. Wager, T A Brocklebank, all ranking among the finest mountaineers of their generation.

The route was the same: the struggle the same, and the result in the case of each attempt too was the same – failure. They were beaten by that terrible last thousand feet.

“The last 1,000 feet of Everest are not for mere flesh and blood,” wrote Frank Smythe afterwards. “Whoever reaches the summit, if he does it without artificial aid, will have to rise godlike above his own frailties and his tremendous environment. Only through a power within him will he overcome a deadly fatigue and win through to success.”

Other “Everesters” have described that “deadly fatigue.” Raymond Green was medical officer in the 1933 expedition:

“This slow upward movement carries with it its own difficulties. At that great height so strong is the wind, and so great is the cold, handicaps actuated by the blood flowing more slowly through the arteries and carrying with it a small freight only of warming oxygen, that a night in the open would surely be fatal . . . in this reduced atmosphere, in which every movement is an effort, where to turn over in one’s sleep-ing bag is to become breathless, where every step is an effort requiring several breaths, physical labour must be undertaken which would be great even at ordinary heights.”

In 1933 came the first plane flight over Everest. Like the climbs it was a British venture, led by the Marquis of Douglas and Clydesdale, later the Duke of Hamilton.

A brilliant series of photographs taken by L V Stewart Blacker, chief observer of the party, show no practical reason why the peak should not be reached. But they suggest no explanation as to the fate of Mallory and Irvine.

In 1934 the mountain was attacked single-handed by an eccentric young Englishman. Maurice Wilson. Disguised as an Indian, he secretly got together a number of experienced Everest guides and left with them for the Tibetan frontier. They took him

as far as Camp Three, but refused to go any higher without ropes.

Wilson continued alone, taking with him a tent, three loaves, two tins of oatmeal, a camera, and a silken Union Jack to plant on the summit.

He asked the porters to wait a fortnight for him. They waited a month. But he did not return.

It was Eric Shipton, leader of the advance party for the fifth expedition, who found his body 21,000 feet up on the East Rongbuk glacier. He had died in his sleep from exhaustion and cold.

Maurice Wilson lângă avion înainte să zboare.,

Tinu2048 – Licence CC BY-SA 4.0

In the spring of 1936 a fully-fledged climbing party was again at the Rongbuk base camp. Bad luck with the weather is the common fate of all Everest expeditions.

But this party had no luck at all. After nearly being swept by an avalanche off the north col it had to withdraw without setting a foot on the mountain itself.

The last full-scale attempt was in 1938. It was led by H W Tilman, who had been on the reconnaissance in 1935. He had with him Shipton, back for his fourth attempt, Smythe and Warren for their third, Oliver for his second, and that old campaigner Odell back for another attempt after 14 years.

The route was the same. Darjeeling – Tibet – Rongbuk – the glaciers. Again they pitched their last camp at 27,000 feet. And again they were beaten by that last thousand feet.

This week another expedition sailed for India. This time Shipton, veteran of four expeditions, will be in command, 44 years old now – old as “Everesters” go. They will be trying from the other side – by way of the south face, which the 1922 team long ago decided couldn’t be climbed. They hope to find a route from there to a south col, 25,000 feet up.

Why do they do it, you may well ask? Is any useful purpose served? These repeated efforts to reach the summit of the world’s highest mountain have already cost human life. They have also cost much physical pain, fatigue, and discomfort.

They have been very expensive. And there is not the slightest sign of any material gain whatever being obtained. And nowadays there is even some doubt whether Everest’s 29,141 feet really is the highest point on the earth’s surface. (During the war there were several accounts of airmen flying the “hump” between India and China being blown off their course at 29,000 feet and looking up at a vast uncharted mountain top.)

Why, then, continue to attack the virtually impossible? It is not enough to reply that valuable scientific study is possible during an Everest expedition, for much of this could be done elsewhere in comparative comfort. Let the “Everesters” themselves try to find the answer.

Wrote Frank Smythe: “In mountaineering, and on Mount Everest in particular, a man see himself for what he is.”

James Ullman recalls how somebody once asked George Leigh-Mallory why he wanted to climb Mount Everest.

Mallory considered for a moment before giving his answer. “Because it is there,” he said.

Note (Courtesy Wikipedia)

James Ramsey Ullman was an American writer and mountaineer.

Text:

The British Newspaper Archive (www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk)

The British Library Board

© Reach PLC

Jerry F 2022