Fourth in a series by my uncle John Alldridge. This article first appeared in the Derby Evening Telegraph in December 1967 – Jerry F

We left the Oregon Trail at Scotts Bluff with 1,200 heartbreaking miles still to go. Instead we turned south and west into Wyoming. We were heading for Cheyenne.

On the map it looks romantic enough; sprinkled with picturesque place names like Lost Spring, Pawnee, Summer, Mule Creek.

But those magnificent American highway engineers have killed off most of the romance.

It is a country of bare prairie on which clouds as flat as dinner plates hang low, in which most oil pumps, like monstrous blackbirds, peck ceaselessly.

For 100 miles and more the great four-lane highway slashes through, like a knife through cheese, running side by side with the Union Pacific, that railroad built with so much blood and sweat and tears.

You pound on for miles over a concrete ribbon forever West, passing always the same corral of white-faced Herefords, the same windmill, the same squashed bodies of coyotes and jackrabbits.

You know that you are getting near Cheyenne when you run into the first tourist trap, with its huge plaster wigwam, its phoney Indian trading post, full of colourful rubbish made in Japan, its “snake farm” showing half a dozen seedy-looking rattle-snakes.

Seen from the road, as it swoops down on the city, Cheyenne looks like a shanty town, a glorious neon-spattered muddle of motels and motor camps and used-car lots, of drive-in movies, drive-in drug stores, drive-in banks, drive-in supermarkets.

In Cheyenne, once the Queen City of the Old West, the parking lot has taken over from the hitching post.

It also boasts aggressively what must surely be the ugliest railway station in the world, a Gothic monstrosity in red brick, half church, half mausoleum.

Cheyenne, with good reason, never took kindly to strangers. This was Saturday afternoon and the temperature was in the high 80s, so most of the 45,000 inhabitants were out of town or taking cover from the heat.

But they had left behind animated traffic signs that bark at you, like angry watchdogs, if you try to cross against a red light.

If the folk are a rough and ready lot it could be because they are descended from men who had to defend what was theirs with a gun — the rancher his cattle, the homesteader his land.

Even today they speak a language direct as it is picturesque.

“All of a dirt son-of-a-bitch and rougher than Holy Hell,” was how the man at the gas station put it when we asked him the condition of the road to Fort Laramie. He couldn’t have described it more adequately.

The unanimous approval of the language as direct as it is.

If the men were tough then their women were even tougher. Here, if nowhere else in the West, the unyielding spirit of the pioneer woman has lasted through several generations.

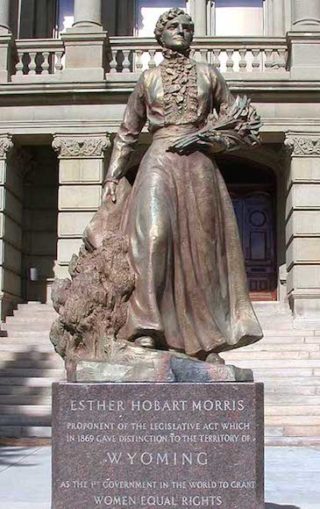

In the forecourt of the State Capitol building in Cheyenne, in the shadow of its imposing golden dome, stands a statue to the memory of Esther Hobart Morris. She carried a posy of wildflowers. But Mrs. Morris was no prairie flower.

Wyoming capitol Morris statue,

Matthew Trump – Licence CC BY-SA 3.0

Long before Mrs. Pankhurst was born Mrs. Morris, out here in sunbaked Wyoming, was fighting for women’s rights.

Her final victory came on December 10, 1869, when with Territorial Legislature, for the picturesque first time anywhere in the world the women of Wyoming got the vote.

Mrs. Morris was also the world’s first woman J.P. In a day and age when most Western Justices of the Peace laid down the law with a gun, that was no idle compliment.

Then there was Mary Lease who led the revolt of the settlers against the big farmers and ranchers in the turbulent 80s.

Every Wyoming child knows her famous battle cry: “The people are at bay. Let the bloodhounds of money who have dogged us so far raise less corn and more Hell!”

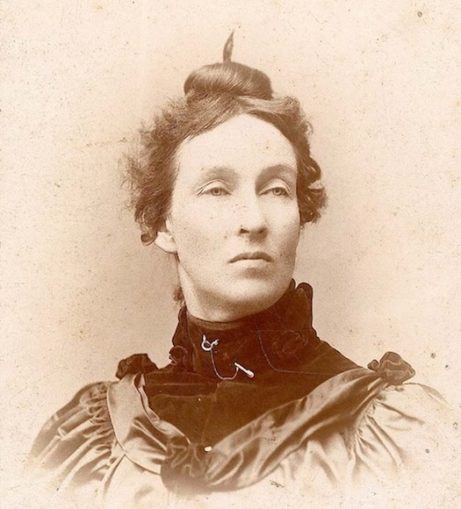

P ortrait of Mary Elizabeth Lease,

Deane – Public domain

Wearing the high-collared black dress that became a sort of uniform, Mary Lease stomped Wyoming and made 161 speeches during the campaign of 1890.

She could out-talk, out-wrestle, and out-argue any man, she boasted . . . “My tongue is loose at both ends and hung on a swivel.”

There was Minna Schwarz, only 12 years old, who in 1877 arrested a bandit who was robbing her father’s road ranch at Pole Creek Station, north of Cheyenne.

I was not surprised to learn that Miss Schwarz afterwards went on the stage and was an enormous success back East in Florida.

And there was Mrs. Ella Watson. better known as “Cattle Kate.”

But in Cheyenne they don’t want to talk about “Cattle Kate.” For the very good reason that “Cattle Kate” was the only woman in the West to be hanged for rustling.

To get the picture straight you must know that in the late ’80s the cattle barons, based on Cheyenne, and the small ranchers and homesteaders were engaged in a bloody feud.

The flash-point was reached after the disastrous winter of 1886-7 when herds were depleted and many ranchers made bankrupt or wiped out.

To add to the troubles of the cattle barons, squatters (or “nesters”) were occupying empty rangeland, homesteaders were staking out claims, while jobless cowboys who had earned a few dollars from their former employers for branding straying mavericks or unbranded cattle, decided to set up on their own account.

Lawless men came down from the barren valleys of North Wyoming and rustled at will.

The free range was fast disappearing under the plough and miles of barbed wire. The old days were going, and the cattle barons, in their plush Cheyenne club, refused to accept it.

They issued a drastic warning that from now on all “mavericks” belonged to the Cattlemen’s Association.

And when the homesteaders and small ranchers, who were branding their own cattle anyway laughed at this, the cattle barons brought in hired gunmen from across the border.

It is a well-worn plot used a thousand times by Hollywood, and never better than in George Stevens’s classic Shane.

Nobody opposed the big cattlemen with more defiance than James Averill, who owned a small ranch in the Sweetwater Valley.

A Cornell man, Averill seems to have developed a Jekyll-and-Hyde personality. Outwardly he was the vigorous champion of the small rancher in opposition to the cattle barons and wrote scorching letters on the subject to the “Casper Daily Mali.”

But on the side he ran a notorious gambling saloon, masquerading as a post office, where all the clientele were male.

When one of his “regulars” suggested that the place might be brightened up by some female society, Averill remembered the buxom Mrs. Watson, lately divorced, who lived in Rawlins.

He invited her to join him. Two weeks later she rode up in a wagon laden with her possessions and moved in.

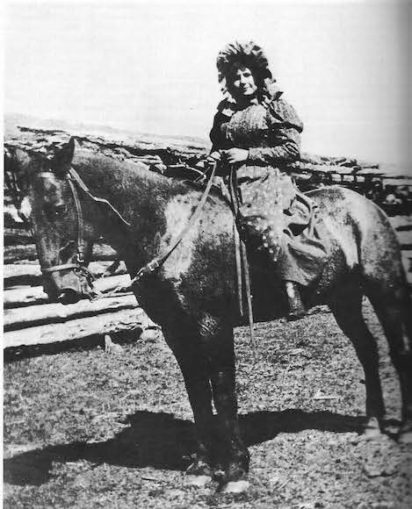

According to the Cheyenne Mail leader, Ella Watson, alias Cattle Kate, was 26, “of a robust physique, a daredevil in the saddle, handy with a six-shooter and a Winchester, and an expert with a branding iron.”

Ella Watson. Taken in the 1880s or earlier,

Unknown photographer – Public domain

Robust she must have been. She weighed all of 180lb. The Averill-Watson partnership was an immediate success. Lonely cowboys rode from afar to enjoy Cattle Kate’s company. If they were short of cash they paid in cattle — usually somebody else’s.

While Kate was entertaining her friends, Jim, assisted by his foreman, Frank Buchanan, was rounding up her “gifts” and putting Kate’s brand on them.

But the combination became too successful. Jim began rounding up mavericks — whether lost, stolen, or strayed — and putting Kate’s brand on them.

Then one unhappy day a local rancher called on Kate and found some of his cattle in her corral.

When taxed with this, Kate reached for her Winchester. The rancher left in a hurry but the word got around.

They might still have got away with it if, some weeks later, Jim had not rustled 20 calves from a big stockman.

Unfortunately for Jim the cattleman had picked out those calves himself. A spy was sent to Cattle Kate’s place and, sure enough, found the missing calves in her corral.

The next day a grim-faced posse called on Kate and loaded her, protesting, into a wagon. They told her they were taking her back to Rawlins.

“But I have not got my best dress on,” protested Kate. “Where you are going you won’t need no dress,” said one of the posse sombrely.

They did not take her to Rawlins. Instead they took her down a canyon to the Sweetwater River, having picked up Jim on the way.

Afterwards they insisted they only meant to scare the daylights out of Kate and Jim. First they threatened to throw them in the river. But Kate was not scared.

“Hell, there ain’t enough water in there even to give you hogbacks a bath,” was her unladylike but truthful comment.

So then they stood them up on a boulder under a cottonwood tree. Two ropes whistled over a branch and settled in nooses around their necks.

Until then it may have been a joke. But at that moment Frank Buchanan, Jim’s foreman, arrived on the scene.

He had sneaked up the canyon and hidden behind a rock just above them. He got one of the posse in his sights and opened fire.

That was too much for the panicky posse. Now the joke had gone far enough. “Jump!” said somebody behind Jim.

When Jim, quite naturally, refused to jump that same somebody pushed him off the rock.

Seconds later Kate followed struggling and protesting to the last.

The executioners were very amateur. Death took a long time.

Six of the seven in the posse were arrested and held for trial. Then Frank Buchanan inexplicably vanished and was never seen again.

The only other witness, a 14-year-old lad, died mysteriously of “Bright’s Disease.” The case for the prosecution collapsed for lack of evidence.

“Is human life held at no value whatever?” thundered the Casper Mail. Apparently not in Wyoming in the ’80s.

NEXT: The lawman who turned killer.

© Reach plc, courtesy of The British Library Board

Jerry F 2022