Sixth in a series by my uncle John Alldridge. This article first appeared in the Derby Evening Telegraph in January 1968 – Jerry F

Some few minutes before four o’clock on the afternoon of August 2, 1876 — right here in Deadwood — a cross-eyed broken-nosed alcoholic called Jack McCall stumbled into Carl Mann’s No.10 Saloon on Main Street.

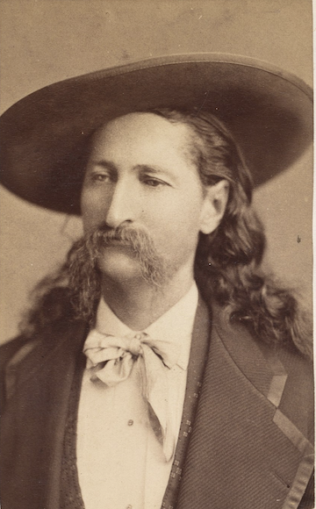

This is a photo of Jack McCall,

Unknown photographer – Public domain

He reeled to a table where four men were playing a friendly game of poker. The cards had been dealt and one of the players — a big man, flamboyantly handsome, with a fine cavalry moustache — was studying his hand when McCall sidled up behind him, drew a gun and shot the big man dead.

It was — you might say — a shot that echoed round the world. Deadwood has been living on it for more than 90 years. For the victim was Wild Bill Hickok, the original Fastest Gun in the West.

Cabinet card photograph of Wild Bill Hickok,

George G Rockwood – Public domain

In fact, after a few hours in Deadwood you begin to wonder what the town would ever have done if Wild Bill hadn’t been shot.

The first thing they do is to take you to the Wild Bill Bar, buy you a beer, and stand you on the very spot where Fate caught up with Bill Hickok.

There is the chair on which he was sitting at the time. There is the headboard from his grave, set up by his sorrowing partner, Colorado Charlie Utter (“Partner, we will meet again in the Happy Hunting Grounds to part no more”).

And, of course, there in the middle of the table is the hand Bill was holding when he died — “aces and eights,” for ever afterwards the Dead Man’s Hand.

Later, in the town’s museum, I was to see the pipe he was smoking — with a few flakes of charred tobacco still in it — a stone from his boot, his razor, and the rusty remains of a pistol he kept in his boot for emergencies.

From the saloon they take you to the baker’s shop just two doors down the street where Jack McCall was caught: then across the road to the Bella Union Theatre, scene of McCall’s trial for murder by a miners’ court which strangely found him not guilty by a vote of 11 to one.

Now all this is very fanciful. For the sad fact is that the original Deadwood — it was no more than a jerry-built cluster of wooden shacks — was destroyed by fire in 1879.

That does not prevent modern Deadwood from keeping green the memory of its most celebrated citizen. And I have no doubt that Mr. Floyd Robinson, who now keeps the historic saloon, makes a nice living out of it. And good luck to him, I say.

For after all, Deadwood was the wildest town in the West, where “the coward never started and the weakling died on the way.” And, for all his faults — and there were many — Wild Bill, that Hollywood-handsome gunslinger with 36 notches on his gun, will always stand for that lawless era.

But it was not Wild Bill I was trailing through Deadwood. I had come here to pay my respects to one of the most controversial, and at the same time most tragic, figures in Western history.

She was born Martha Jane Canary. But to the miners and gamblers of Deadwood Gulch — as, later, to the world — she was known as Calamity Jane.

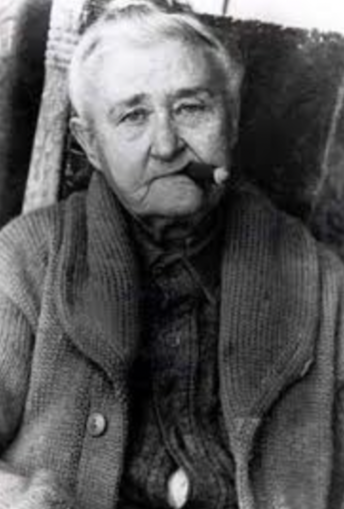

Calamity Jane,

Unknown photographer – Public domain

In Calamity, fact and fiction are inextricably tangled. As long as books are written about the West, Calamity will he part of them. And as long as such books are written historians will take sides for or against her.

If you belong to the anti-Calamity party, she was nothing but a foul-mouthed slut who swore like a trooper, smoked like a chimney, and drank like a fish. If you are pro-Calamity, as I unashamedly am, then she is a tragic example of a woman born 50 years before her time.

Perhaps Miss Perragoue, of Deadwood’s Chamber of Commerce, summed her up to me better than most: “Calamity could do almost anything a man can do, and sometimes rather better.”

Almost anything a man could do Calamity did do. She drove a bull-train for the army in the Black Hills expedition and shocked even the soldiers with her cussing. Certainly she drove the Deadwood Stage from Cheyenne to Deadwood. (The famous old stage is carefully preserved, bullet holes and all.)

She hit Deadwood in the seventies and it was her base from then on. It was about this time that she earned her nickname. “Here’s Calamity!” they would shout as Martha Jane swaggered into a saloon, firing her six guns at the mirrors . . .

But there was a softer, unexpectedly feminine, side to this tall, unexpectedly hard-faced woman. When a Home for Wayward Girls needed funds Calamity took up a collection at pistol point.

When Deadwood was ravaged by smallpox she nursed the sick devotedly. We have this on the authority of Dr. Babcock, the town’s only doctor who years later told how Calamity risked her life to save many a dying miner.

One of her patients was a small boy called Robinson. To him Calamity was efficient if rough-handed apt to growl: “Here, drink this, you little bastard,” or “Damn it, keep still while I wash your face.”

The romance — if such it was — of Wild Bill and Calamity has been built up into Deadwood’s second best selling legend. The facts are rather different.

When Wild Bill finally arrived in Deadwood in 1876 his days of glory were long since over. No longer the trouble-shooting Marshal of Abilene and Hays City, Bill was a sick man of 39 worried about his eyes. He was, in fact, that classic Hollywood figure — the ageing gun-fighter who can’t hang up his guns.

To the horny-handed, warm-hearted Calamity he must have seemed like a Greek god earthbound in the Black Hills of Dakota.

Whether Bill ever loved Calamity is debatable. She was probably no more to him than an amusing incident. But there is no doubt at all that Bill was the love of her life.

She never got over his death. Afterwards she disappeared from Deadwood and drifted aimlessly about the West, drinking her way into oblivion while the legends grew around her.

There are still people in Deadwood who remember her return in 1900 — a woman looking older than her age; shuffling down Main Street dragging behind her a seven-year-old girl (which the legends insist was Bill’s and most certainly was not).

The end came for Jane in a Terry boarding house not far from Deadwood on August 2, 1903. She opened her eyes at the last and asked what day it was.

When they told her she nodded and whispered: “It’s the 27th anniversary of Bill’s death.” Then — “Bury me next to Bill.”

They did. She sleeps now beside the grave of Wild Bill Hickock, up on the hill above the town. The man who closed her coffin was the Rev. C. H. Robinson, rector of Mount Moriah Cemetery. He was that little boy Calamity had nursed through the small-pox plague.

Her funeral, they say, was the biggest Deadwood has ever seen. They had come in their hundreds, not to bury an unhappy, broken woman, but to lay away a legend.

Deadwood has always been a tough town. It has always had its “characters,” real or invented. There was Deadwood Dick, for instance. In fact there were three separate Deadwood Dicks. Originally the brain-child of a writer of Western paperbacks, Edward L. Wheeler, Dick became so important to Deadwood’s tourist trade that the town decided to bring him to life.

There was the Englishman, Potato Creek Johnny Perrett, who dug up the biggest gold nugget in Deadwood’s history. And there was Poker Alice Tubbs, also from England; so called because of her talents at the faro and poker tables of the West and South-West.

Pic 4 – Poker Alice Tubbs

Courtesy of the South Dakota Historical Society

Courtesy of South Dakota Historical Society,

Unknown photographer – Public domain

Poker Alice set up a gambling hour in Deadwood and did a rousing business. She was never seen without a big black cigar smouldering in her mouth, and kept order at her tables with a gun. In her time she won a quarter of a million dollars.

Poker Alice made her last bet in 1929, when the doctors told her an operation might save her life. She lost.

Nowadays a thriving community of 3,500 lusty souls, poured into a narrow wooded gulch high up in the Blackwood Hills, Deadwood is still a pretty lively town; particularly on Saturday nights when the miners from the huge Homestake Goldmine at Lead, three miles away, come in to “hurrah” the town.

Before I left Deadwood I climbed the hill to the cemetery to pay my last respects to Calamity Jane, she lies where she always wanted to be, in a handsome grave beside her Bill.

Someone, I noticed, had planted a lily on her grave. It was only when I looked closer that I saw it was plastic.

NEXT: The Army that fought the Indians.

© Reach plc, courtesy of The British Library Board

Jerry F 2023