Arthur Scherbius,

Colored – Licence CC BY-SA 4.0

It is indeed strange that the names of the people listed in the article title should remain so completely unknown today.

Great innovators of the Weimar Republic during the 1920s, people like Gropius in architecture, Planck in physics, Brecht in theatre, still command instant recognition. Even the lesser lights like the film director Fritz Lang or the Gestalt psychologist Wertheimer continue to shine within their own disciplines. But Scherbius, as influential a figure in cryptography as the others in their fields, a man whose work had a critical effect upon the shape of WW2, & swayed the outcomes of battles on both land and sea around the world, has been condemned to obscurity. The fact is, without Scherbius there would have been no Enigma ciphering machine, & without the machine, no possibility of an Allied victory.

From the moment that details drip-fed into the light of the 1970s of the critical struggle in the second world war to decrypt & read messages sent via Enigma, all manner of books, plays, TV documentaries & films (not to mention innumerable sites on t’interweb), have been devoted to the story. Apart from the more-or-less factual accounts, the 1980s gave rise to Hugh Whitemore’s play Breaking the Code, later televised by the BBC, the 1990s produced Robert Harris’s novel Enigma, followed by a film, the Noughties gave us the full Hollywood treatment in U-571, (very) loosely based on Royal Navy crew retrieving Enigma files & machinery from a sinking U-boat, & the 2010s the story of Alan Turing & his work at Bletchley Park in The Imitation Game.

Such a concentration of interest so long after the event suggests that there is something in the nature of the story that exerts a particular hold on the imagination. In his (still) unrivalled history The Codebreakers, David Kahn made reference to cyphers as the protective carapace that valuable information requires, as much as the tortoise relies on its shell, and from before the time of Julius Caesar they have been regarded as one of the weapons of war.

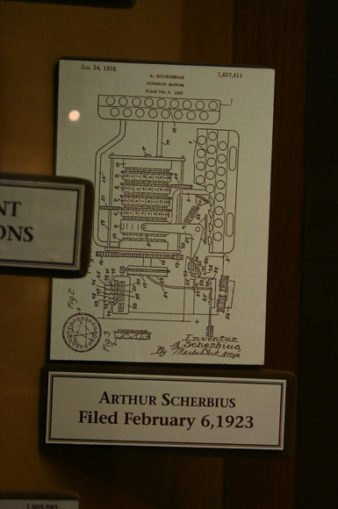

Arthur Scherbius Patent Filed February 6, 1923,

Ryan Somma – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

Essentially, any cipher, however sophisticated, disorders the pattern of a message so that it becomes unreadable without a key, & part of the appeal of Enigma undoubtedly lies in the voyeuristic pleasure of reading what was intended to be secret. The machine that Scherbius developed from a Dutch invention was effectively an electric typewriter, but instead of the power running directly from keyboard to keys so that a tap on the key A produced an A on the paper page, the current ran through a number of rotating wheels each of which scrambled the sequence ensuring that the A key produced any letter but A on the paper. Its original purpose was commercial, and industries such as German railways & Swedish steel makers used it for sending sensitive information, but it was the adoption of Enigma by German & Japanese forces in the 1930s that transformed it into a weapon of critical importance.

German / Deutsch Enigma Machine: World War II Museum, New Orleans, Lousiana, USA,

Bogdan Migulski – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

The strategic importance still continues to fascinate. It was Enigma that enabled Admiral Doenitz to gather U-boats into deadly packs undetected, & to wreak such havoc on Atlantic convoys that Britain came close to being stifled into submission. It was the Americans’ restricted ability to read Purple (the Enigma derived Japanese cipher machine) that allowed Admiral Yamamoto to assemble his fleet in secrecy for the surprise attack on Pearl Harbour. By contrast, when Bletchley Park cracked the German Army’s use of Enigma, it gave British commanders the advantage of knowing Rommel’s intentions in advance throughout the North African campaign. On the other side of the world, when Purple was broken it allowed the aircraft carriers of the US just enough time to arrive in strength & destroy the cream of the Japanese fleet at Midway in 1942. The prize, in short, could hardly have been greater.

In the 1920s, while Scherbius was working out how to scramble the patterns of written communication, a few miles away in the University of Berlin, Max Wertheimer was developing the theory that the capacity to recognise patterns is hotwired into the human brain. This ordering capacity is not only innate, but integral to civilisation & sanity itself. Indeed, some of the most compelling evidence for Wertheimer’s theory comes from the mental breakdowns suffered by the code breakers, who could not stop their minds trying to worry sense out of the chaos. That intellectual contribution to the struggle has been well documented – the sheer brilliance of mathematicians such as Alan Turing & Hugh Alexander, the hours of intense concentration in Hut 6 Bletchley Park, the repeated frustrations & barely understood mathematical formulae which eventually uncovered patterns in the chaos of letters produced by Enigma. But the physical bravery which brought them the cipher books & rotor wheels they absolutely needed in order to know how to approach the problem – that side of the story has been less often told. And this was a problem that had to be solved from scratch almost monthly, as although a version of Enigma was broken by Polish intelligence as early as 1933, the nature of Scherbius’s machine enabled it to be constantly upgraded, using ever more complex electrical settings………………

On 9 May 1941, Sub-Lieutenant David Balme shouted the order to lower the ship’s sea-boat into the swelling mid-Atlantic. Three hundred yards across the waves, there wallowed his destination, a stricken German U-boat, stern down. Balme and his men were from the British destroyer Bulldog, the leading ship in the 3rd Escort Group accompanying convoy OB 318. Her fellow escorting vessel, the corvette HMS Aubretia, had forced the U-boat to surface with depth charges, and Bulldog’s gunfire had damaged her & she had been abandoned by her crew. Balme’s armed boarding party, which rowed across, had orders to strip her of anything useful. Unaware that the sub was unmanned, Balme clambered up her curved, slippery surface, and, revolver at the ready, mounted the fixed ladder of the 12ft conning tower. Going down inside, he had two hatches and more ladders to negotiate. An eerie blue light bathed the U-boat’s nerve centre in the chamber below, an array of unfamiliar wheels and dials.

A hissing came from somewhere, and he could hear the ocean slosh against the hull. There might be booby traps; there might be scuttling charges set to explode. He went up to the bow: nothing; the stern, too, was empty. He formed his men into a chain to pass out books and documents. They included a stoker, Cyril Lee, and a telegraphist, Allen Long. The stoker’s job, to restart the engines, proved too risky, but the telegraphist at once told Balme: “This looks like an interesting bit of equipment, Sir.” It resembled a typewriter, but lit up strangely when Long pressed the keys. It was a German naval “Enigma” cipher machine. The party found daily settings and procedures for its use. Written in soluble ink, they risked being lost if dropped in the sea, but, Balme recalled: “nothing even got wet.” It took him and the party, Lee, Long, together with Able Seamen Sidney Pearce, Cyril Dolley, Richard Roe, Claude Wileman, Arnold Hargreaves and John Trotter, six hours to clear the U-boat. The discovery allowed Bletchley Park codebreakers to penetrate the German cipher called Hydra.

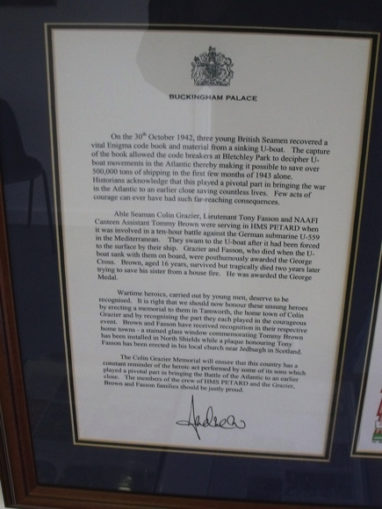

Bletchley Park – Hut 8- The HMS Petard Story – Tamworth Herald on the Anchor’s – letter from Prince Andrew,

Elliott Brown – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

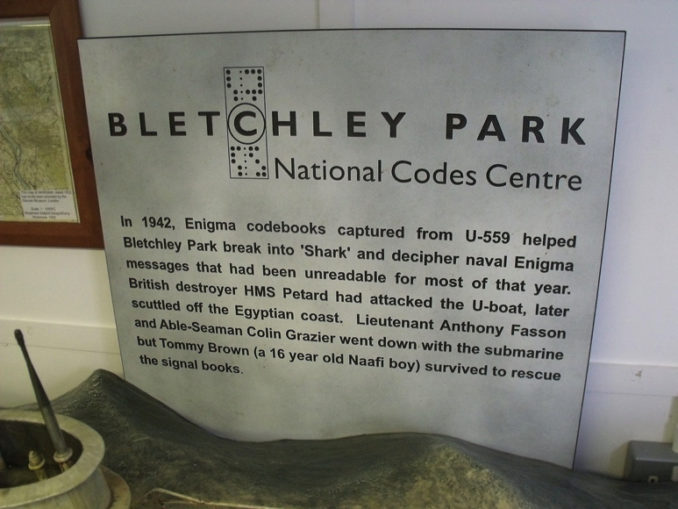

On October 30 1942, HMS Petard and its crew, in company with three other Royal Navy ships, was steaming to waters off Port Said on the Egyptian coast to investigate reports of radar contact with a German submarine. A sustained depth charge attack was laid down, eventually forcing the U-559 to the surface, and after Petard’s 4” guns caused serious damage the crew started to abandon ship. Quick action was needed if the submarine was to give up any secrets. Lt. Tony Fasson together with Able Seaman Colin Grazier dived into the sea and swam across to the stricken vessel, followed in one of Petard’s boats by 16-year-old canteen assistant Tommy Brown. Clambering down into U-559 the men made their way to the captain’s cabin where they found two codebooks printed in water-soluble ink. Passing them out to Brown they went back into the submarine to continue the search. Now knee-deep in water they were attempting to wrench some equipment from its fixings when Brown shouted a warning to get out. As they started up the ladder U-559 made her final dive taking Tony Fasson and Colin Glazier with her. They would never know the importance of their actions and nor, thanks to the cloak of secrecy that was thrown around the incident, would anyone else for a very long time.

In fact, the documents they rescued, a Short Weather Cipher (Wetterkurzschussel) and Short Signal Book (Kurzsignalsheft), would turn out to be absolutely priceless. Back in Bletchley Park codebreakers had hit a brick wall after the Germans introduced a fourth rotor into their brilliant Enigma machine code systems. For months the upgraded M4 Enigma TRITON, named after the son of the Greek sea god Poseidon, had Bletchley’s best brains stumped. Closeted in Hut 8, cryptanalysts had given their task the code name SHARK but they had yet to sink their teeth into TRITON. It took 24 days to get the codebooks from U-559 to Bletchley and the breakthrough came on December 13. The short weather cipher was precisely what the cryptanalysts needed. They learned that the four-letter indicators for regular U-boat messages were the same as those for the three-letter indicators with the addition of one added letter. This meant that once a daily key was found for a weather message the four-rotor signals needed to be tested in only 26 positions to find the full key. Solutions to the hitherto impenetrable four-rotor Enigma messages between U-boat command and vessels on active duty soon began to flow. Only an hour after the first decrypts were made intercepts of U-boat signals were sent to the Admiralty’s submarine tracking room – revealing the positions of 15 submarines.

For the first time in a long time, U-boat movements were exposed and the use of long-range bombers and aggressive anti-submarine tactics gradually turned the tide in Britain’s favour. The scale of the breakthrough can be gauged by the fact that close to a million tons of shipping and the lives of many seaman, were saved in December 1942 and January 1943 alone. The incredible secrecy surrounding Bletchley Park and all things Enigma meant that the U-559 incident never really received the recognition it deserved.

Bletchley Park – Hut 8 – U-VII,

Elliott Brown – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

Bletchley Park was a remarkable moment in intellectual history, the point at which the capacity of the machine first began to outstrip the complexities of the mind. (Insert theme from Terminator………..) For it was in 1943 that the Post Office’s Dr Tommy Flowers first constructed Colossus, the world’s first electronic computer, to automate the decoding of the Enigma ciphering machine. Today, when every bit of computer information is electronically coded, from ASCII to sophisticated encrypting systems using secret-key algorithms, which can generate uncrackable ciphers, we depend totally on the machine to make intelligible the most trivial of messages. Nostalgia makes us yearn for the man versus machine heroics at Bletchley Park, but those in the Royal Navy who made the ultimate sacrifice in repeated raids on ships, supply vessels, & U- boats to secure the all-important cipher books & associated paraphernalia also deserve their place in the pantheon of WW2 heroes.

Bletchley Park – Hut 8 – The HMS Poppy Story – Poppy wreath,

Elliott Brown – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

© 2021 DJM

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file