Introduction

Everybody knows how to use money, but very few people understand what it really is, or how it works.

You might think people who work in finance and banking understand money, but I’ve not met one yet. There are a handful of politicians who understand it (one of them is Bill Cash), but most happily wallow in their ignorance.

I’ve often seen Puffins ask questions about money, or express frustration at how impenetrable the monetary system appears. Hopefully this article will help answer some questions. I’ve tried to keep it as simple as I can.

Understanding money will give you valuable insights into economics, politics and history – so is worth some effort.

The Theory of Money and Credit

A comprehensive explanation of money first came about in 1912, when Ludwig von Mises – leading member of the ‘Austrian’ school of economics – published The Theory of Money and Credit. Mises’ explanation remains (in my opinion) the best. As you would expect, there are different theories of money, usually tied to political ideologies. The Austrian School tilts heavily towards free market principles, and against excessive government. It sees money as a ‘market phenomenon’ and is in favour of ‘sound money’ – typically gold. Other theories, such as Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), see money as a creation of the state.

Ludwig von Mises Institute, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

How money began – from barter to a common medium of exchange

Mises believed that money evolved from barter. Let’s say I have a wooden bowl, and you have a hat. I want the hat more than my bowl, and you want my bowl more than your hat – so we exchange. The problem with barter is that it requires a ‘coincidence of wants’. To overcome this challenge, I could trade my wooden bowl for another commodity – one which I don’t want for its own use, but which is more marketable. Let’s say I trade for a bag of salt. I can then go to the market with my bag of salt and trade that for what I want. Certain commodities, such as salt, would become desirable simply because they facilitated exchange so well. Over time, commonly accepted mediums of exchange would emerge, aka – money. Although economics books talk of other uses for money – e.g ‘as a store of value’, the fundamental purpose of money is always as a medium of exchange.

Many different commodities have emerged as money in different places at different times. Sea shells, pearls, precious metals, cigarettes in prisons etc.

Prices

Once you have a common medium of exchange, goods and services start being priced in units of the money. How do these prices form? Economists used to believe things had an objective value based on how much labour went into producing them. Prices were thought to accurately measure this value. Even Adam Smith thought this. But this is wrong. In the 1870s economists worked out the theory of subjective value. Individuals value things based on their desires. This is then expressed through exchange, just as we saw in our barter example. If I value a suit of armour more than 5 ounces of gold, I will want to exchange the gold to buy the armour. Conversely, for the exchange to happen the owner of the armour must value the gold more than the armour. A price is therefore a subjective exchange ratio – ie. 5 gold to the armour. With lots of people exchanging all the time, market prices form for different goods and services. Prices frequently change because subjective values change.

Beyond commodity money

So far our story of money is quite straightforward. We can imagine an ancient city where goods and services are bought and sold for silver and gold coins. The ruler of the region is likely to want to stamp his image on the coins, but he cannot do the same for pieces of wood and decree them of equal value because people would not subjectively value them the same as gold.

How did we get from this state of affairs to the polymer bank notes in your wallet, or the digits in your bank account?

Mises classified different categories of money, all of which could be used as mediums of exchange.

- Commodity money – as discussed, a medium of exchange which is also a good in its own right.

- Money substitutes – this is a token that someone has issued that can be immediately redeemed for a specified amount of money. These tokens can then be used as if they are the same as the money, so long as there is confidence they can be redeemed.

- Credit money – these are future IOUs for money, which then get used as money because they are generally accepted by people.

- Fiat money – money given its status by a legal authority. Fiat: “let it be done”

One of the problems of using commodity money is being able to assess quality and quantity. In our ancient city, the ruler therefore sets up a mint to standardise coinage. Other rulers nearby do the same. Common denominations and names emerge so that people can identify coins they trust. (A pound was a pound of silver. Dollar derives from “thaler” a coin first minted in 1519). Goldsmiths set up banks to look after the commodity money. They issue receipts in the form of money substitute tokens, which are then used as money. Occasionally, our ruler needs to spend a lot of money on a war, and so issues IOUs, which get used as credit money in the same way. But the citizens can still convert these all back to gold and silver coinage, or they would reject these other forms of money.

Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license

The problem of commodity money

This was how the world worked for a long time, until governments eventually succeeded in moving away from commodity based money and onto fiat money. For governments, the disadvantage of commodity money is its scarcity – they must tax or borrow it from their citizens in order to get their own to spend.

It is important to appreciate that although scarcity of money is unwelcome for anyone who wants to spend more of it, it is a crucial feature for a successful medium of exchange. Mises made the point that there is always enough money in the economy as a whole to do its job. This goes against the theory of monetarism, which believes the quantity of money needs to be controlled by a central authority, such as the central bank (eg. quantitative easing). Mises recognised that because the medium of exchange is effectively chosen by people automatically, and because prices are simply exchange ratios that can flex up and down, there is always enough money. Indeed, Austrian economists blame monetary policy for causing booms and busts.

From commodity money to fiat currency

As we have discussed, money substitutes can be converted back into commodity money. Our fourth category of money, fiat money, is not redeemable into anything. Legislation just says certain pieces of paper issued by the state are money. But how could governments overturn the subjective value judgements stretching back through millenia which chose commodities as money? How could they successfully establish fiat money with a recognised purchasing power in the minds of the people?

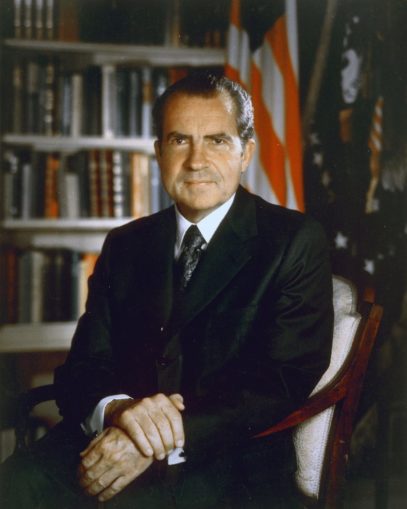

The first part of the process was for the state to control the issue of money substitutes. Just as it had controlled standardisation of commodity money through the mint, it did the same thing issuing money substitute bank notes from its central bank. These were redeemable into the commodity money and so everybody recognised these money substitutes as money. No one else was allowed to issue other money substitutes as legal tender. Over time the state could then slowly reduce the convertibility of the money substitutes into commodity money. For example, it could decree that the money substitutes will not be immediately redeemable, but treated as credit money for a few years (which happened during WW1). It then lowered the conversion rate of the substitutes in a series of incremental changes. Eventually, governments stopped conversion completely, thus successfully making the transition to having a fiat currency, and overcoming the problem of money scarcity. This was achieved in 1971 when President Nixon announced that US dollars were no longer convertible to gold.

Now you know why a £10 note says “I promise to pay the bearer” – it is merely an echo from when the note was a money substitute for commodity money, rather than the fiat money it is today.

Oliver F. Atkins, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The Regression Theorem

The reason people ascribe a certain value – or purchasing power – to a particular money is because they know through using the money the level of purchasing power it had the day before. They expect it to also have that purchasing power today, and tomorrow. You can therefore trace this process backwards through time. Mises wrote that every example of money can be traced back through time to a starting point as a commodity that was valued for its non-monetary use. The subjective value of the £10 note in your pocket regresses all the way back to the first cavemen finding pieces of gold and giving them to their wives.

The reason Nixon could eventually sever the dollar’s link to gold is because in peoples’ minds dollar bills still held (roughly) the same purchasing power the day he severed the link as the day before. Similarly, the euro was able to replace the deutschmark because on its first day it was seen as a substitute to the deutschmark at a certain conversion rate – the purchasing power was carried over.

Many Austrian economists use the regression theorem to claim that cryptocurrencies are flawed as money – because they cannot fulfil this regression back through time to a commodity used in its own right. As such, they contend that no one can say with confidence what a cryptocurrency is worth, hence their extreme volatility.

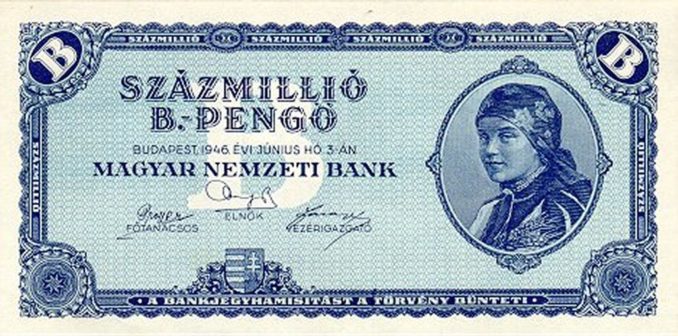

The printing press and quantitative easing

Freed from the physical discipline of money tied to commodities, governments with a fiat currency found they could create new money at will. This gave governments and its friends more purchasing power. Of course, as people perceive more money in circulation, prices inevitably rise negating the effect. But there is a time lag to this, and those spending the money first always benefit at the expense of those who get it last.

Magyar Nemzeti Bank (Hungarian National Bank), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Today, there are laws forbidding governments from directly creating money to spend. It is illegal under EU law. In order to spend, the government must either tax or borrow money first. However, the central bank can electronically create fiat money through a simple accounting entry and use this for the monetary policies we mentioned earlier. It can then use this new money to buy the debt the government has just issued. Quantitative easing is money printing by the government but shrouded by legal form, and with an economic theory that supposedly justifies it.

Commercial banks – fractional reserve banking

It is now time to bring the banks back into our story. When we left them they were helpfully safeguarding commodity money for their customers and issuing money substitutes, so people didn’t need to carry around bags of gold. Just as we have seen the state coming up with crafty ways to manipulate money to their advantage, commercial banks also came up with a similar ploy – fractional reserve banking.

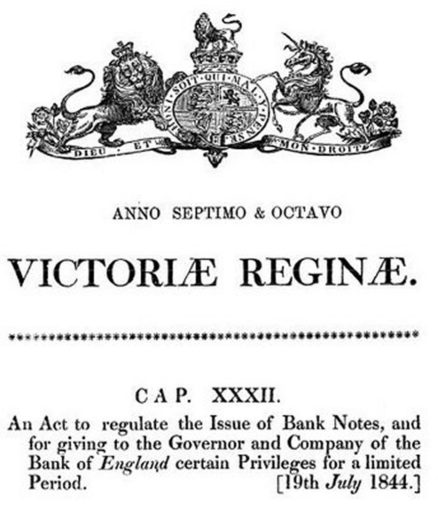

When banks held their customer’s money, they found that they could lend it out and charge interest. However, they were not allowed to lend money that had been deposited for safekeeping. To do so was considered fraudulent. Similar protection is still in place today – it is called Client Money regulation. If I deposit some money with my stockbroker for example, then the broker is required to safeguard it and not use it themselves. This sounds great, but there is one problem – it no longer applies to banks! (Indeed, if you want a smart alec definition of a bank, it is anyone who is not subject to Client Money regulations.) The Bank Charter Act of 1844 got rid of the distinction between bank deposits for safekeeping and for lending. This allows for fractional reserve banking where banks not only lend out the money deposited with them for safekeeping, but can lend out more money than the deposits they hold.

Unknown authorUnknown author, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Bank payment systems

Explaining how bank payments work helps to further explain fractional reserve banking. The first thing to understand is that banks are just big accounting systems. A bank can create a loan on its books by recording a credit entry in your bank account along with a debt entry for the same amount . If you pay this money from your account to someone else’s account at the same bank, the bank simply transfers the entry across to the other account. This process creates money. When you repay the loan your debt and credit entries just cancel out. This cancels money. If there was only one bank in the world there would literally be no limit to this loan and money creation. It would just be the bank moving numbers around its different internal accounts. The limitation for the bank comes when you want to send the money to someone at a different bank, or withdraw the money as cash.

Central bank money vs bank credits

By this point you may be wondering how the money the bank created as a loan “out of thin air” relates to the fiat money the state creates using the central bank. Although both types of money appear exactly the same to us, one is central bank money, the other is just a commercial bank accounting entry. Bank notes are a physical substitute of central bank money. They are your way of holding a little bit of central bank money. (That’s why it says Bank of England on it.) This means if you deposit a £10 note at your bank, you are actually exchanging central bank money for a bank accounting entry – essentially a promise from your bank to pay you back in central bank money. You are lending your bank money.

Going back to bank payment systems. How do I send some of the loan money I now have sitting in my bank account to my friend with an account at another bank? Well, I could withdraw a £10 note, give it to my friend and he pays it into his bank. Effectively, my bank will end up holding £10 less central bank money and my friend’s bank will hold £10 more. This is basically how an electronic payment works but without moving physical cash. The banks all hold an account at the central bank and they settle payments between themselves by transferring between these accounts. Before fiat money, the same thing would happen but with settlements of physical gold. Some payment systems settle payments immediately. Others wait until lots of payments have been made between banks, and then only settle the net difference at the end of the day. A cheque is just a slower version. To allow this system to work, the amount of central bank money only needs to be a fraction of all of these bank accounting entries in existence.

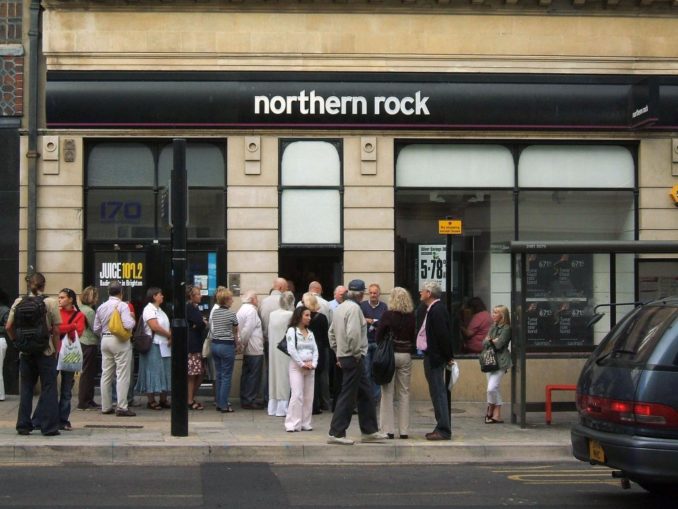

It is the central bank system – consisting of balances of fiat currency held by banks – which is the foundation of our monetary system. Each country will have a central bank for its own currency, and every time bank credits move between different banks, the banks will ultimately need to settle their differences with the relevant central bank – in central bank money. If they cannot do this, they go bust. Banks call central bank money “high powered money” because they recognise its importance. This is why when there is a run on a bank, its customers try to withdraw their money. They are trying to either hold central bank money directly (in the form of bank notes), or transferring their money to another bank that they think will have enough central bank money to settle their payments in the future.

Dominic Alves from Brighton, England, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Is gold money?

JP Morgan famously said, “gold is money, everything else is credit”. Based on the definitions in this article, we could say gold is not currently considered money because it is not a commonly accepted medium of exchange. Shops do not price in gold. However, because gold has a globally recognised market price, it can quite easily be sold to get money, and we can perhaps imagine someone accepting it directly as payment. The same is true though of a barrel of oil, or an ounce of platinum. However, central banks still hold large reserves of gold. I’ll leave it up to you to decide what’s going on.

Money today

Today, money is really only the balances we see in the banking system – denominated in the fiat currencies we recognise – together with banknotes issued by central banks. As we have seen, most of this money is in the form of accounting credits, supported by a smaller foundation of balances held by the banks within the central banks, which are used to settle payment systems. As a result, money today is really only given effect when we move these balances in exchange. Every time this works – ie. when the system successfully settles a transaction – we have confidence that we have money.

© JimmySP 2021

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file