Public Domain

“[Johnson had] the utter inability to comprehend the questions of morality or ethics raised by his actions, an utter inability to feel that there was even a possibility that he had violated accepted standards of conduct and might be punished for that violation.” [The Years of Lyndon Johnson: Volume 2: Means of Ascent (1990) – p. 357]

“For a President to preserve as a personal memento a photograph showing the notorious Box 13 in the possession of his political allies—a photograph which by implication proves that someone was indeed in a position to stuff it—is startling in itself. For him to display the photograph to a hostile journalist is evidence of a psychological need so deep that its demands could not be resisted. It is continuing evidence of the fact that not even his possession of the presidency had eased the insecurities of his youth.” [Vol. 2 – p. 402]

Challenging the Outcome: Injustice and Guilt

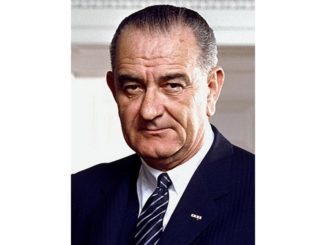

Lyndon Johnson had won the 1948 Democratic nomination for the vacant Texan Senate seat against Coke Stevenson by the narrowest of margins and had used staggeringly illegal means to do so. The outcome was naturally disputed by Stevenson and his supporters, particularly in view of how one-sided the late returns were, with Johnson getting nearly all of those votes, especially those of the Precinct 13 or “Box 13” which ultimately decided the incredibly tight election in the latter’s favour, winning as he did by just 87 votes.

Although voting irregularities were common in Texas politics, especially in the Valley area, nothing like this had been seen before. Stevenson decided to act and sent attorneys to Precinct 13 to investigate but they were initially prevented from seeing the tally list. One witness who did manage to see it claimed that around 200 entries from the end, beginning at number 842, the colour of the ink changed from black to blue. When it was finally, briefly allowed to be shown to Stevenson and his people, they noted the change of ink but also something more significant: the fact that the last 201 names (200 of whom had apparently voted for Johnson), beginning at number 842 on the list, were in alphabetical order beginning with names that started with A, up to 915, and then started again with A and ran alphabetically once more, as if someone had miscalculated the number of required votes and had to begin again to ensure enough names were listed. Also, the 841st voter stated that he had arrived around twenty minutes before the voting place closed and believed he was the last voter.

Stevenson raised federal and state court cases and also appealed to the Democratic Party, who would determine the nomination at their upcoming convention. Johnson was able to take advantage of a wider schism in the Party involving States Rights Democrats who broke away from the national ticket and supported J. Strom Thurmond over President Harry Truman. In what was a close fight Johnson would ally himself with Truman’s liberal “Loyalists” to unseat States Rights advocates from convention posts. They in turn were willing to connive with him to prevent the votes from Precinct 13 from being opened, something which would have embarrassed Johnson and displayed the corruption that had been involved in his victory and which Stevenson’s people sought to prove their case.

Meantime, Johnson deflected, saying that it was Stevenson who had stolen votes, not him. He was able to use his extensive radio coverage to transmit this message widely. A temporary injunction was obtained by his lawyer ally Alvin Wirtz to prevent the Jim Wells County return from being revised. Herman Brown, Johnson’s ally at Brown & Root, was able to get several members of the Executive Committee of the Democratic Party convention onside by cajoling them and also indicating that further contracts and subcontracts that the firm had provided to their areas would no longer be available if Johnson lost the vote.

Johnson won at the convention, by one vote, but the legal challenges would go on and Stevenson was able to obtain a restraining order preventing state officials from putting Johnson’s name onto the ballot list. He also extended the fraud charge to different counties. His lawyers in the Federal Court argued before Judge T. Whitfield Davidson that they brought their case on civil rights grounds, as not only was Stevenson denied his federal right, but so were the voters. The judge at one point suggested a compromise where both names would go on the state ballot. Stevenson was content with this but Johnson was not. He was in no mood to compromise, despite the advice of his lawyers to the contrary, which angered him. He had been endorsed by his party and felt he had an advantage that he didn’t wish to let go of. Force of personality made him adamant that he would not back down but things were looking far from positive.

The injunction keeping Johnson’s name off the ballot was allowed to continue. Worse still, ballot boxes were to be opened. In particular, ballots and/or a list from Box 13 could contain the evidence of the extra 200 Johnson votes that were found and that had ultimately made the difference in the outcome. His entire political future was at stake. He didn’t even have his seat in Congress anymore, with a Democratic candidate nominated and an election pending there. The Judge’s injunction had to be overturned, quickly.

[Public Domain]

Although the view among Johnson’s other lawyers was that they should strongly appeal the injunction to the Circuit Court, followed by the United States Supreme Court if need be, Fortas said this was unrealistic as it would take too long and would make it too difficult to get Johnson’s name on the ballot in time, given the other orders that would be required and delays due to appeals that would be brought by Stevenson. Even if Johnson could obtain victory in court, it would still be a defeat in terms of the election.

The best solution, Fortas believed, was to get a stay of injunction to allow Johnson’s name to be put on the ballot list. This would require a Supreme Court Justice to make such a decision but they would have to go via the Circuit Court first and this would take time before it could be considered there and then appealed if the outcome went against Johnson. Fortas’s suggestion then, was that they present a case to the Circuit Court which, whilst competent, was a bare-bones one and was as likely as possible to be rejected so it could then be promptly appealed to the Supreme Court, where the decision they sought seemed more likely – Fortas calculated that a Supreme Court Justice was more likely than a Circuit Court Justice to make a decision that overruled Judge Davidson in the Federal Court. The grounds would be jurisdiction, i.e. that Davidson was incorrect in taking authority over the case. This would mean essentially surrendering one of Johnson’s chances of winning an appeal in favour of gambling on a Supreme Court victory alone. Johnson decided to go with what Fortas proposed.

Meanwhile, as other proceedings unfolded in relation to the investigations into ballot-rigging, evidence started to disappear. Luis Salas claimed that thieves had stolen everything from his car, including the ballot lists. It seemed if there was a ballot list remaining, it would only be found in the box containing the Precinct 13 votes. Salas and others would appear in the Alice Courthouse, where there was a prospect of boxes being opened, at the same time as Johnson’s lawyers were arguing elsewhere to get the stay of injunction. The timing would be incredibly tight.

Events unfolded the way Fortas predicted: the Circuit Court rejected the deliberately weak case Johnson’s lawyers presented, allowing them to speedily appeal to the Supreme Court. When the matter called there Justice Hugo Black agreed with Fortas’s assessment that it was not for a federal judge to conduct the contest of an election in a state. He granted the stay of injunction, not a moment too soon as at the same time Salas was taking the stand in the County Courthouse in Alice and boxes were starting to be opened (though not the box from Precinct 13 – Stevenson’s people hoped that a remaining copy of the ballot list would be found within, which could have proved his allegations, though if it wasn’t found its very absence along with the supposed ‘theft’ of the other copies was in itself was highly suspicious). Federal Master William R. Smith, presiding over matters in the Alice Courthouse, was contacted by Judge Davidson’s office to advise of Black’s Supreme Court ruling and was told to proceed no further. The other boxes were not opened and it was never established if another copy of the ballot list was contained in one of them.

Stevenson tried to petition the Supreme Court to reconsider the stay of injunction but was unsuccessful, as was a later petition for a trial. Fortas’s plan had worked with possibly just minutes to spare (though it is questionable if Parr or Salas would have allowed the ballot papers or list for Box 13 to be produced). Stevenson kept trying but Johnson’s name went onto the ballot and he easily won the Senate election against his Republican challenger in November 1948.

A further twist occurred when a Duval County Deputy Sheriff, Sam Smithwick, who was in prison for murdering a radio news commentator who had attacked the corruption of Parr’s regime, reached out to Stevenson to tell him he could recover the missing Box 13, which he had been told to destroy. But when Stevenson set out to meet him, he learned along the way that Smithwick had apparently committed suicide in his cell. Caro notes that no evidence has been found to link Johnson to Smithwick’s death but rumours would persist over the years, and suspicion generally about the circumstances surrounding the 1948 election and Box 13 would continue even as Johnson’s standing in national politics grew, particularly when people lost trust in him during his presidency. Salas, in an interview several years after Johnson’s death, admitted that he had previously lied and the election had been stolen, though his claims were dismissed by the Johnson estate.

Initially Johnson did nothing to dispel the stories and rumours about the dubious outcome of the election, referring to himself by the ironic name “Landslide Lyndon” and even showing a degree of pride in the fact. Caro points out that Johnson seemed to want to project the image of himself as a manipulator, as someone who could outsmart an opponent. He wanted to be seen as a pragmatist, not an idealist like his father. He soon tired of the name and of references to the election and when he later began considering a run for the presidency he tried to play down the earlier impression he had given but even then he couldn’t resist boasting about how he had outsmarted Stevenson. In 1967, when being interviewed by a journalist Ronnie Dugger at the White House in his bedroom, he produced a photograph:

“…The photograph is of five smiling men gathered around the front hood of an automobile with a “Texas-1948” license plate. Balanced on the hood of the car is a ballot box, marked “Precinct 13.” The men are Ed Lloyd, the attorney who ran Jim Wells County for George Parr, and who was Johnson’s leader there; Parr’s cousin, Givens Parr; County Sheriff Hubert Sain; Sain’s immense, pistol-carrying deputy, Stokes Micenheimer; and another Johnson ally in Jim Wells, Barney Goldthorn. As Johnson returned with the photograph, Dugger was to write, “he held it forward to me with a kind of pride.… The President watched my face as I searched the photograph for its meaning,” and “as I got it … he grinned at me with a vast inner enjoyment.”” [Vol. 2 – p. 401-2]

Salas also possessed a copy of the photograph, which he showed to Dugger later. As Caro notes regarding Johnson [see the second epigraph at the top of the page] this was startling behaviour and indicated that even when he had eventually attained ultimate power as President, he remained a deeply insecure man.

Aftermath

Public Domain

There is an irony and perhaps some form of justice in that, despite being two decades older than Johnson, Stevenson would outlive him, and not only that but he would live a reasonably happy and contented existence on his idyllic estate, remarrying and having a daughter. (His first wife had died back in 1941.) Stevenson would still bear scars over Johnson cheating him out of a position in the Senate that should rightfully have been his but seeing his tranquil life one columnist wondered if he hadn’t been lucky to have lost that election. Johnson, despite the immense power that he would go on to acquire, would remain deeply insecure and although eventually achieving his wish and becoming President, even being hailed for his “progressive values” he would ultimately end up reviled by many, particularly for his actions in Vietnam.

This lay some time ahead though. Initially, Johnson appeared to have regained his momentum, continuing his rise and going on to gain unprecedented authority in the Senate, using his ability to spot power where others hadn’t by becoming Minority and later Majority Leader. The role of party leader in the Senate had been something of a nominal position, if not a poisoned chalice, responsible for scheduling business but with little real authority.

The Senate itself had become a stumbling block to any effective legislation or change but Johnson, with the help of the influential Senator Richard Russell, would turn convention on its head, carving out for himself a position of power unparalleled in the Senate before or since.

Johnson would streamline the processing of business, turning the Senate into a legislative machine, making it quicker in tabling and passing bills; scheduling with Senators as to which bills called and when, in such a way as to leave them beholden to him; forcing Senators to find agreements to get bills passed promptly, using procedural changes and coercion to do so. Arguably his most significant achievement there was being able to push through the 1957 Civil Rights Act, the first of its kind since the previous century – it was ultimately rather toothless (arguably it had to be in order to prevent more significant opposition from the South, whose Senators had successfully opposed and filibustered any such bills in the past) and it was of limited scope compared to what he would do as President, but symbolically it was significant and it bolstered his image for a presidential run.

Although he could display compassion for the poor and for ethnic minorities who were discriminated against, journalist Ronnie Dugger was to describe his compassion as “real, though expendable” and Caro, though also believing Johnson had genuine compassion, notes that this would take “a back seat to calculation”. [Vol. 3 – p. 734] Johnson also continued to show his ruthlessness, destroying the career of Leland Olds, Chairman of the Federal Power Commission to suit oil interests and he pushed Senators into voting particular ways in spite of the detrimental effect their votes might have in their constituencies; those who defied him were frozen out, obtaining none of the most-desired committee positions, good offices or other perks that were within his power to offer. He also continued to obtain high contributions from businessmen in return for government help.

Johnson hoped to receive the Democratic nomination for the presidency for 1956 but it soon became apparent he would not succeed. He hoped for it again in 1960 and this time it was a more realistic proposition given his stature, rise to prominence and the civil rights achievement under his belt, but it quickly became apparent that the man who was normally so good at reading other men had misjudged the situation and instead of going all-out for the nomination by courting various Governors and seeking the votes of states who might well have been receptive to him (despite his Southern origin, which was deemed to be a disadvantage) he sat back and waited, thinking his best chance would be to win as a candidate in the horse-trading that he expected would happen behind closed doors. He simply didn’t believe that any candidate would win outright, particularly not Jack Kennedy. He was sorely mistaken and Kennedy, who was both well-organised and -supported, won, but when offered the Vice Presidential slot by Kennedy, Johnson accepted, to the surprise of many given how the position had little power. He had hoped to carve out his own powerful niche, as he did with the Senate, but he was mistaken again: Kennedy was a more shrewd character than Johnson thought and was not going to give him unprecedented powers in that role, which could have undermined his own position. (The Senate, too, prevented him from retaining any of the power he had built up there when he tried to hold onto some of it.) The years as Vice President would bring frustrations similar to those he felt between his 1941 and 1948 Senate campaigns.

In the closely-fought 1960 presidential election there were allegations of vote-rigging, particularly in Illinois, where 650 election officials were charged with voter fraud, though not convicted (several were convicted in 1962 after an election judge confessed to witnessing vote tampering). But Texas, Johnson’s home state, although it received less attention, was another area where there were allegations of voter fraud, which have persisted to this day.

Johnson’s allies like George Parr remained in position in 1960, still able to count votes for him. Parr could turn against public officials who showed inadequate allegiance but Johnson was not one of those: he helped Parr obtain a presidential pardon for income tax evasion in 1946 and later provided him with legal help via Abe Fortas, who represented Parr pro bono in attempting to overturn a 1957 mail fraud conviction. It was within Johnson’s interests to assist Parr in order to ensure his silence about the 1948 campaign.

As Caro notes, it is difficult, essentially impossible, with the passage of time to verify how much weight can be assigned to the “ethnic bloc” vote, given that there are a number of factors to consider. However, in 1960 the percentages from Parr’s areas were similarly high in Kennedy’s favour as they were for Johnson in 1948: more than 88 percent in the heart of Parr’s Rio Grande domain, with corresponding numbers in other areas controlled by Parr and his allies. Given that Kennedy won Texas by 46,223 votes and taking into account that Parr’s nine counties delivered a plurality of over 21,000 votes for them, whilst San Antonio, controlled by Johnson allies the Kilday brothers, saw a reversal from Republican to Democrat of around 31,000 votes from the result of the previous election, it is fair to say that Johnson’s allies played an important part in gaining Texas, with 24 electoral college votes which, combined with Illinois, with 27, brought enough electoral college votes to take Kennedy over the finishing line.

Public Domain

In view of all Johnson’s ruthlessness, amorality and avidity for power, some might ask if he was cold-hearted enough to have later had any role in President John F. Kennedy’s assassination, as has been suggested over the years. Caro, who has spent more of his life studying Johnson than anyone (his research and writing on Johnson has been going on for well over four decades) says he has found no direct evidence for such claims. Although some biographers get too close to their subjects, Caro has never held back from displaying in stark detail the awful side of Johnson’s character – indeed it is his writing that has done more than anyone else to reveal the extent of it.

However, it is notable that Johnson’s circumstances in the lead up to Kennedy’s death were such that if he hadn’t become President at that point he probably never would have done: at that time he was under investigation by the Senate for financial irregularities regarding his former Senate aide Bobby Baker, who had been caught up in stories about having wrongly used his influence and position to benefit private firms who he received money from – some of these dealings also involved Johnson; he believed he had limited time to reach the presidency given that the men in his family tended to die young (and he was a number of years older than Kennedy anyway) and he had already had a heart attack in 1955; he had been stifled in his position as Vice President, which he had hoped to have turned into something far more influential than had been possible before; he had lost popularity in the South, with his support and influence there being a large part of why Kennedy had chosen him as a running mate; and he was losing influence to others, including the President’s brother Bobby, who seemed an increasingly more popular possibility for running mate looking ahead to the 1964 election.

Johnson might not have been involved in Kennedy’s death, but the circumstances were nothing if not convenient given everything that was going against him at that moment, less than a year before the next presidential election. But these factors, however convenient, do not constitute proof, unlike what we know of his other schemes, manipulations and illegalities to attain power, where the evidence is clear.

Legacy

Caro has yet to cover the events following on from the “passage of power” in the months following Kennedy’s assassination (covered extensively in his fourth volume) where Johnson managed to pass major tax cuts followed by the historic 1964 Civil Rights Act, legislation which Kennedy would have struggled and probably failed to pass had he lived – Johnson had a knack for vote-counting along with unique talents in influencing and cajoling people. Hopefully, despite Caro’s advancing years (he is 85 at the time of writing this) he will manage to complete his concluding volume to round off his masterful work on Johnson’s life.

It might be worth providing some discussion of those subsequent events in Johnson’s life. While he won some significant initial legislative victories, followed by a landslide election win and obtained the ultimate power he craved, having managed for a time, as Caro notes at the end of his fourth volume, to rein in the worst aspects of his personality in order to achieve these things, he would ultimately come undone.

There is something of the Shakespearean tragedy about it: the vaulting ambition; the fatal character flaw; the dramatic rise and equally-if-not-more spectacular fall, assisted by outside forces.

For all of his power and initial achievements, his overly-ambitious “Great Society”, despite some successes and a number of institutions that have endured to the present day, including Medicare and Medicaid, produced a great many failures; his “war on poverty” would create a culture of welfare and dependency and would lead to mass disintegration of the black family, something which as has been pointed out, even slavery failed to do. In the decades since, dramatic increases in the rate of black single-motherhood, soaring crime in black communities and educational disparities between the poorest and the most advantaged that have failed to close in the decades since, all indicate that the various endeavours of Johnson’s administration, it failed on precisely the issues where they were supposed to succeed. However, some still laud Johnson today for his “progressive values” which apparently matter more to some than cold hard facts.

But whatever the differing views on his domestic agenda and legacy, he would be widely vilified and his record permanently damaged – and in many ways defined – by his decisions concerning Vietnam. American involvement in that country had long preceded Johnson’s tenure, but he greatly exacerbated the situation. Johnson seldom miscalculated in his career but when he did so, it was spectacular and costly, none more so than here.

Having done so much initially to rein himself in and to emphasise a continuation of Kennedy’s policies in order to hold onto the supporters of his slain predecessor – even though he went much further than Kennedy could or would likely have done – he began to feel the need to be seen to step out from Kennedy’s shadow. This conceit, despite his initial caution over Vietnam, led him to escalate the conflict.

There were of course other factors at play, like the “domino theory” of the wider Cold War, which suggested that if one country was allowed to fall to communism, others would surely follow. And Johnson was arguably too willing to listen to the advice of certain members of his cabinet, like Robert McNamara, McGeorge Bundy and others: the advice he received, favouring a gradual escalation over large and sudden military strikes, combined with Johnson’s wish to be seen as a strong leader but also his continuing reticence to take large steps in the conflict, meant that the situation gradually developed into a quagmire that became increasingly costly, in lives and resources.

The proposed heavy bombing campaign around Hanoi in February 1965 which could have made a significant impact and might even have brought the conflict to a swift resolution, was called off by Johnson at the last minute and cabinet advisers appear to have deliberately attempted to frighten him against it. There are other examples of instances where more decisive action might also have shortened the war and yet were not followed through. It has been argued too that the joint chiefs, being poorly led by their own chairman Maxwell D. Taylor and failed in their duty, allowing themselves at times to be deceived while also telling Johnson what he wanted to hear, not what he needed to. However, Johnson’s handling of Vietnam and the advice he received is a complex topic and one for a different discussion.

Regardless of poor advice, external forces and wider geopolitical considerations, Johnson’s arrogance and ambition – constant threads throughout his life – had a major part to play in his decisions and in classic Shakespearean fashion, they would destroy him. Perhaps in this his story also resembles another type of tragedy, the Greek variety, where excessive pride and arrogance, or hubris, is inevitably followed by retribution, or nemesis.

But in addition to his domestic and foreign policy decisions, and to return to the main topic of this series, Johnson also left another baleful legacy: one of amoral politicking, corruption, voter-fraud and election-theft – hardly new concepts in US politics, either before his time or afterwards, but the means, extent, organisation and outright flagrancy have been without modern parallel until the most recent US presidential election.

Indeed the similarities are striking. Take the following examples: an ambitious and ruthless candidate/party who will stop at virtually nothing to attain power; the extensive use of secrecy and underhand methods; the blatant campaign lies, smears and whispering campaigns against opponents; the control and use of influential media outlets to spread falsehoods on a huge and damaging scale; the vast and unprecedented sums of money thrown around; the connivance with big business and the mutual back-scratching involved, with business interests doing all they can, to the point of illegality, to lever in their favoured candidate; the massive, powerful and corrupt political machines involved; the last-minute theft of elections and the ability of one candidate to ‘find’ the necessary votes despite trailing the other candidate by a significant margin; significant numbers of fraudulent votes, sometimes involving the names of the dead; all of these display the significant parallels between today and Johnson’s time and methods.

There is also the outright buying of votes, perhaps not quite as flagrant now as in Johnson’s time (or indeed before that in e.g. the notorious Tammany Hall era) where money was sometimes literally handed out to voters, but truthfully it is only a little less obvious today, with some politicians who will appeal not only to big business for help in return for favours, as previously mentioned, but who will essentially engage in ‘buying’ the votes of poorer and ethnic minority voters and their community leaders through handouts.

There are other echoes of that time too: the rise of a populist (O’Daniel/Trump) with no prior political experience who gained election by seeking to get rid of career politicians, whilst opposed at every step by legislators, big business interests and the media; or a President/candidate (Roosevelt/Biden) threatening to pack the Supreme Court; or the legal challenges, attempts to frustrate them and efforts to have matters proceed to the Supreme Court, sometimes using deliberately weak cases beforehand to rapidly progress matters to the highest judicial authority (something the Republicans appear to have learned from the Democrats in their recent legal challenges).

Whether you take the view that history repeats itself, or prefer the line often but inaccurately attributed to Mark Twain that “History doesn’t repeat itself but it often rhymes” (Twain never actually said this – he did come up with something similar in meaning, albeit expressed in a less-pithy manner) there is certainly plenty of repetition and rhyme to be found in recent US events with those that can be traced during Johnson’s life and career.

Some of these are incidental, and a number have been witnessed on other occasions. However, when we look at the corrupt methods and amoral tactics that Johnson deployed, we see that he was directly responsible for innovating many of these and became the standard-bearer for them. He brought these machinations into the mainstream of modern US politics to the extent whereby they became both acceptable and instructive to those who were willing to prioritise power above all else, including morality. The underhand approaches used in the most recent presidential election campaign appear almost as if they were copied directly from his playbook.

Johnson wanted power more than anything, and he got it, but in the end, for all of his schemes, it didn’t work out how he hoped. Perhaps it is a timely reminder for politicians in particular to be careful what they wish for; and to the rest of us to be especially careful who we vote for.

Further reading:

Robert A. Caro – The Years of Lyndon Johnson, Volume 1: The Path to Power (1982)

Robert A. Caro – The Years of Lyndon Johnson, Volume 2: Means of Ascent (1990)

Robert A. Caro – The Years of Lyndon Johnson, Volume 3: Master of the Senate (2002)

Robert A. Caro – The Years of Lyndon Johnson, Volume 4: The Passage of Power (2012)

Robert A. Caro – The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York (1974)

Robert A. Caro – On Power [audiobook] (2017)

© The Black Swan 2020

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file

Audio Player