I qualified as a public health inspector (PHI) in Hull in 1968 and after a couple of years with a rural district council in South Norfolk, at the tender age of 22 I found myself working as ‘Additional PHI’ to the Littleborough Urban District Council near Rochdale in what is now part of Greater Manchester. I still don’t know why I went there and I only stuck it out for seven months but a couple of things that happened during my brief stay will be forever imprinted upon my memory.

In those days, prior to the 1974 Local Government reorganisation that created the much larger District Councils and changed my job title to environmental health officer (EHO), one of the principal attractions of working in public health and hygiene was the sheer variety of duties that were involved. We seldom knew what challenges each day would throw at us and that’s largely what made the job so enjoyable prior to the need to specialise in specific disciplines that came in with larger local authorities. In the 1960s and early 1970s our duties included among many other things the inspection of premises under the Offices, Shops and Railway Premises Act of 1963; restaurant, café and hotel inspections under the 1960 Food Hygiene Regulations; food poisoning outbreak investigations; dealing with statutory ‘nuisances’ as set out in the 1936 and 1961 Public Health Acts; meat inspection at abattoirs; noise and air pollution control; pest control and housing condition surveys to determine fitness for human habitation. On one memorable occasion I even had to supervise a pre-dawn exhumation at a cemetery.

The four year day-release training course had rigorously combined theory, practice and law. For example, all PHI students had to be able to recite by heart Section 4 of the 1957 Housing Act that set out the list of criteria to be considered when determining a dwelling’s fitness for human habitation as they were often required to do so at the dreaded final oral examination. Amazingly, I can still recite Section 4 using my personal mnemonic ‘Really Superb De-Luxe Volkswagens Don’t Fail’ that was prompted by the 1962 1200 Beetle I owned at the time. For anyone remotely interested, the matters to be taken into account involved the assessment of the state of Repair, Stability, freedom from Damp, natural Lighting, Ventilation, Drainage and sanitary conveniences and facilities for the storage, preparation and cooking of Food and the disposal of waste water. Prior to the 1970s, housing condition surveys had mainly been aimed at identifying areas for slum clearance, particularly in the North West but with the passing of the 1969 Housing Act the emphasis changed wherever possible to housing improvement through local authority ‘Improvement Grants,’ which I really enjoyed doing.

Can it really be more than 50 years since I committed Section 4 to memory? It seems like yesterday.

After growing up on the flat, reclaimed marshlands of the West Riding/Lincolnshire border and my then recent period of employment under the vast skies of Norfolk, Littleborough came as a bit of a shock situated as it is in the foothills of the South Pennines. Hills took a lot of getting used to.

The A6033 Todmorden Road out of Littleborough as I remember it (I have never been back) was very steep, climbing up one of the hills to the area known as Summit beneath which passes the 2,885 yard long former Manchester and Leeds Railway Summit Tunnel that was opened in 1840 and whose 12 remaining orientation/ventilation shafts can still be seen crossing the moors.

Some distance up the hill on the left hand side of the road as you leave Littleborough stands a row of Victorian terraced cottages that in 1970 were unusual in that they still had a long-obsolete type of outside toilet at the ends of their back yards that were known locally as ‘tippers’ or ‘tipplers’. At that time I had never even heard of a ‘tippler’ or ‘automatic slop-sink closet’ as they were also known which were mainly confined to working class housing in the industrialised regions of Lancashire and West Yorkshire although in 2007 the Hungate archaeological excavations in York revealed a row of five Duckett’s tipplers that would have been used communally by an estimated 50 people in what in the 1930s was a slum area of the city. The long-buried tippler mechanisms were found still to be in working order more than 100 years after they were installed. This type of appliance was popular in the latter part of the 19th century but by the outbreak of the Great War they had fallen out of favour for being unhygienic and decidedly malodorous. One of their main drawbacks was that they could only be provided externally to a dwelling.

Closet Conversion Grants

The 1936 Public Health Act (see below) gave local councils the power to require the replacement of insanitary closets with water closets and to encourage take-up they were also given discretion to pay a contribution (not exceeding half) towards the cost of the works to the owners of such properties. Where necessary, the council could carry out the works themselves and subsequently recover half the costs from the owner.

[CH. 49.] Public Health [26 GEO. 5. & Act, 1936. 1 EDw. 8.]

47.-(1) If a building has a sufficient water supply and sewer available, the local authority may, subject to the provisions of this section, by notice to the owner of the building require that any closets, other than waterclosets, provided for, or in connection with, the building shall be replaced by waterclosets, notwithstanding that the closets are not insufficient in number and are not prejudicial to health or a nuisance.

(2) A notice under this section shall either require the owner to execute the necessary works, or require that the authority themselves shall be allowed to execute them, and shall state the effect of the next succeeding subsection.

(3) Where under the preceding subsection a local authority require that they shall be allowed to execute the works, they shall be entitled to recover from the owner one-half of the expenses reasonably incurred by them in the execution of the works, and, where they require the owner to execute the works, the owner shall be entitled to recover from them one-half of the expenses reasonably incurred by him in the execution thereof.

(4) Where the owner of a building proposes to provide it with a watercloset in substitution for a closet of any other type, the local authority may, if they think fit, agree to pay to him a part, not exceeding one-half, of the expenses reasonably incurred in effecting the replacement, notwithstanding that a notice has not been served by them under this section.

(5) The provisions of Part XII of this Act with respect to appeals against, and the enforcement of, notices requiring the execution of works shall apply in relation to any notice under this section requiring a person either to execute works or to allow works to be executed, subject however to the modifications that no appeal shall lie on the ground that the works are unnecessary and that any reference in the said provisions to the expenses reasonably incurred in executing works shall be construed as a reference to one-half of those expenses.

My role in all this, as my boss patiently explained, was to supervise the conversion work in order to ensure that everything was done in accordance with good practice; to test the new drains on completion of the works and to ensure that the new toilets were connected to the public sewer. After the successful completion of all this I was to sign off the works so that the Council grant could be paid.

Fair enough, but what the hell was a tippler closet? I’d never even heard of them let alone seen one.

The Tippler Closet

On the face of it, the idea of using waste water from the kitchen sink to flush the toilet was forward-thinking enough to excite even today’s Green activists. In a tippler, instead of going direct to the sewer, ‘grey’ water from the sink discharged into a three gallon capacity hopper below ground level. When the hopper was full it overbalanced on a pivot with a loud ‘clunk’ tipping its contents into a drain that in turn discharged into the base of a deep circular shaft. At the top of this shaft was a wooden toilet seat set on a glazed stoneware pedestal.

At a rate depending entirely on sink usage the tippler would empty itself, automatically flushing the toilet contents into the sewer. Well that was the theory but the downside was that the toilet contents would lie festering until the next flush and the sides of the shaft between the seat and the annular basin which sat far below at its base received no cleansing rapidly becoming clagged-up and foul smelling.

Using these toilets was not for the faint-hearted as no one could predict when the tippler would discharge with its spooky, subterranean sounds. Housewives soon overcame this uncertainty by the simple expedient of leaving their kitchen taps running so as to provide a constant trickle of water into the hoppers thus ensuring regular flushing throughout the day and night. However, the consequent waste of potable water began to alarm local councils (who were charged with its provision) and as a result tippler closets rapidly fell out of favour.

Many of those who had to use tipplers have described how frightened they were as children upon hearing the system operate and the sudden rush of water anything up to eight feet below them. It can’t have been pleasant to have spent their childhoods with a morbid fear of falling into the Stygian depths of their ‘long drop’ or ‘whistle and drop’ lavvy and being washed away never to be heard from again.

If only Stephen King had lived locally, Pennywise the Dancing Clown would have worn a flat cap and overalls and said, “They all float down ‘ere. When you’re down ‘ere wi’ us …… you’ll float too, tha knows,” in a Fred Dibnah accent. It’s the stuff of which nightmares are made. (Stephen King “It” (1986))

One Lancashire plumber Alan Garvey recalled that when he was newly married in 1948 his wife was so frightened at the prospect of using the tippler at the end of the yard that she wouldn’t go near it.

The outside Loo frightened Kath by its 8ft depth and she never used it. She would go to the Toilet at work before coming home and not go again until she was back in her office the next day. I cannot remember what she did at weekends. But I converted that Toilet within three weeks of taking the house. As there was no hot water or bath in the house I cobbled up a gas washing boiler on the shelf in the rear bedroom and fitted an old bath that we had removed during some one’s modernisation. When we needed a bath I would light the gas boiler and wait 20 minutes to run a bath for Kath and then add a drop of warm water for me. It worked O.K. The old slop-stone-sink in the kitchen went out and I fitted a 36″ combination sink and drainer on legs under the kitchen window. For hot water we used a Maxell Gas Geyser with a spout over the sink

(Alan Garvey, 2016). Chartered Institute of Plumbing and Heating Engineering

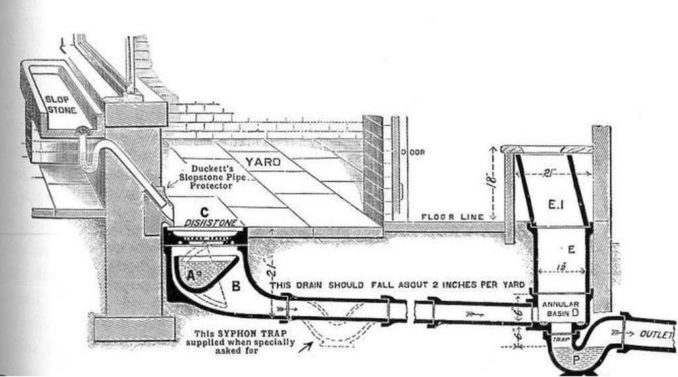

The above diagram shows how the tippler system worked. A slop sink incidentally is a long, narrow (3ft x 2ft), salt-glazed earthenware, and hence cheaply manufactured, fitting. They should not be confused with the currently trendy deep, white porcelain ‘Butler’s sinks’ as slop sinks, which were yellowy-brown or dark brown in colour, were no more than three inches in depth. As they were not fitted with a plug, domestic pot washing and doubtless personal hygiene too had to be done using an enamel bowl. Waste water along with the grease, tea leaves, soap scum and any other detritus that it contained was discharged into an underground earthenware hopper situated either under the sink gully in the yard just outside the kitchen or, depending on the topography as was the case in Littleborough, at the base of the toilet shaft itself. When the hopper was full, it tipped its contents into the connecting drain or directly into the annular basin (‘D’ in the diagram) flushing the toilet contents out towards the sewer.

The closet pictured above, the type used in Littleborough, would have been situated at the bottom of a deep shaft six to eight feet below the toilet seat with the hopper being filled via a drain connected to the house sink gully. The pipe shown filling the hopper with clean water has been installed in the museum purely for demonstration purposes and would never have existed in practice.

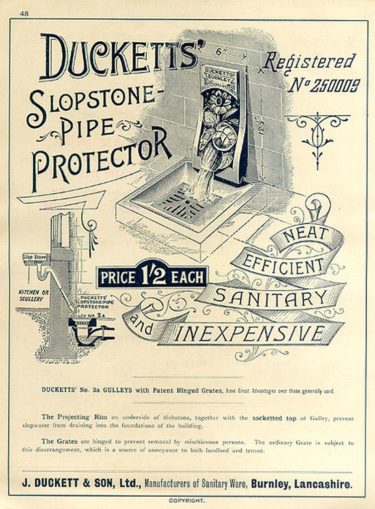

The waste pipe from the slop sink was made of lead and therefore vulnerable to being damaged. To avoid this happening, Duckett’s produced an ornate stoneware ‘slopstone pipe protector’ as is shown fitted in the above diagram.

Inspecting the works in progress

On the day that the builders turned up on site to do the conversion they asked me to visit to discuss my requirements. Naturally, being completely out of my depth I’d have been more than happy simply to have left them to their own devices but after bluffing my way through the meeting I left the builders with instructions not to backfill the new drains until I had tested them and confirmed their connection to the main sewer in Todmorden Road.

Everything progressed smoothly and after a couple of days I was asked back to carry out my final inspection. To do this, I first had to arrange for the council’s sewer gang to lift a manhole cover in the middle of the busy A6033 so that they could give me a thumbs up when the water from the test flushing of the newly installed WC reached them. First I tested the new drains for water-tightness and then proceeded to empty a sachet of drain tracing dye into the toilet before flushing it a couple of times.

Here I should explain that the drain trace that we used was a substance called fluorescein, an orange-red powder which on contact with water turns a brilliant green colour. Those of you who have had your eyes examined at the hospital may well have had fluorescein drops applied to their surface in order to show up any damaged areas. Fluorescein was used by downed aircrews to indicate their position to Air-Sea Rescue craft during the War.

As I sauntered casually to the main road via the new inspection chamber in the access way I confirmed the presence of dye in the invert as I passed. When I waved to the sewer gang foreman to let him know that the flushings were on their way all I received was a shrug and a ‘no joy’ gesture. This was strange as sewage should have been running down the steep gradient of Todmorden Road at the speed of an express train. They must have missed it… so, I put another packet of dye in the toilet and flushed it a couple more times just to make sure. This time I walked down the main road to see the sewer for myself. No, the sewermen were right, there wasn’t a trace of green to be seen and by now I was getting the distinct impression that they thought I was a bit of a prat. Bugger, I’d been rumbled!

Back up the hill, another couple of packets of dye and another half dozen flushes later and still no thumbs-up from down the hill. I was beginning to despair so, to gather my thoughts I walked across the road to lean Last-of-the-Summer-Wine-like on a stone wall and think things through. Now let’s see; the water from the toilet is going down the drain and is going somewhere but it isn’t reaching the sewer so……..oh bloody hell! Out of the corner of my eye I suddenly noticed a fluorescent green rivulet coursing across the field immediately in front of me in which pigs were happily rooting while far below in the valley the River Roch was now completely day-glow green as it flowed placidly towards Rochdale. The builders had only connected the toilet into an old surface water drain instead of into a foul drain that communicated with the public sewer!

Nothing more could be done that afternoon so I dismissed the not too subtly smirking sewer gang and told the builders to make the trench safe but to leave the drains exposed until the following morning when I’d return and sort things out. In truth I hadn’t a clue what I was going to do. Fortunately I had recently made friends with the council’s Building Inspector and when back at the council offices I explained the circumstances he kindly offered to accompany me the following morning and give me the benefit of his experience and local knowledge. When Ron visited the site he agreed that the builders had simply connected into one of the hundreds of old and unmapped surface water drains that were all too common in such a hilly location. The challenge now was to find the correct drain into which to divert the new toilet. But how were we going to locate it? “Easy,” he replied, “I’ll get my divining rods from the car. Be with you in a tick.”

Now I’m a sceptical type and don’t hold with Ley lines, astrology, crystals and New Age Glastonbury mumbo-jumbo so the sight of a man holding two bent welding rods walking slowly across a site access did not inspire me with confidence. But when the rods both slowly and of their own accord moved inwards to lie across his body my eyes just boggled. “Dig here,” he said to the builders, marking the spot with a drag of his heel. I’m pretty sure that they like me thought they were on a fool’s errand but builders, if they have any sense, soon learn not to argue with building inspectors and so they set to with picks and shovels and soon, to my and doubtless their utter amazement, exposed the top of a 4” salt-glazed drainpipe a couple of feet below the surface. When cracked open it was obvious that this was indeed a foul drain/private sewer.

Once the new WC drain had been diverted into the newly discovered pipe and made good, all that remained was for me to check once again with the sewer gang who, to my immense relief, gave me the hoped for thumbs-up and the job was a good’un.

To my surprise I never heard any more about my polluting local watercourses with drain tracing dye but if I had, I would have denied all knowledge and blamed a downed pilot. The one upshot was that the next day Ron presented me with my own set of divining rods which to my surprise I found that I too could use for detecting long-forgotten drains and water pipes.

Showing off at the slaughterhouse

Another incident took place one day when my boss was away on holiday. Our office clerk on hearing that I was off to do the day’s meat inspection asked if he could come with me as he’d never seen the inside of an abattoir. I was happy to oblige so I kitted him out with a white coat and hat and took him along with me, pleased to have a spectator whom I could impress with my knife-wielding expertise and anatomical knowledge.

As killing had finished for the day, the beef carcases were hanging on the rails in the cold store and the heads and ‘plucks’ of offals had been left out for my attention on racks in the slaughterhall. When inspecting a beast’s head, the meat inspector follows a set routine, making a series of palpations, observations and incisions to expose various lymph nodes (retropharyngeal, sub-maxillary and parotid) and to check for the presence of Cysticercus bovis (cysts of the beef tapeworm Taenia saginata) that are communicable to man in the masseter muscles of the jaw. I had done this hundreds if not thousands of times without incident over the years and had developed a technique of which I was very proud of swapping hands so as better to incise the left and right internal and external masseters.

Holding the wet, slippery flesh in my left hand I cut the left side muscles with the knife in my right and then with a stylish ‘swish-a-swish-swish’ of my razor-sharp boning knife on the steel hanging from my belt and with the showmanship of Keith Moon twiddling his drum sticks, I threw my knife in the air, caught it beautifully with my left hand and then cut straight through the right side external muscle in the beast’s jaw slicing off the tip of my finger as I did so. It wasn’t a particularly serious wound but the flow of blood was quite spectacular and poor Eric, who to his credit didn’t laugh too much simply said in his broad Lancashire accent, “I’d best get thee to th’ospital.”

© text Tom Pudding 2020

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file