The City of Dresden in 1945

Unknown author / Public domain

A rather strange myth had grown over the city of Dresden since the mid-1940s. That is was a benevolent municipality, untouched by the horrors of the war raging around, but not in it, like a Germanic version of Trumpton, cruelly singled out for destruction by the whim of one man, Air Chief-Marshal Arthur Harris. But the citizens could bear witness to the war that they were losing, simply by watching the tens of thousands of German soldiers in the trucks that filled the wide main roads and choked the bridges. They were heading east with what few serviceable tanks and munitions could be mustered, in an attempt to stem General Zhukov’s Red Army, while countless numbers of refugees from the East were fleeing the Russian arbitrary murder and rape of civilians. To the West the British and American forces were advancing, following the failed Ardennes Offensive, which had bled Germany dry in blood, fuel and armour.

The few Jews still not deported from the city to the death camps were crammed into specially assigned apartments, run down, mainly unheated and subjected to daily harassment from the authorities. On 8th February 1945, following a meeting of the Nazi Peoples’ Court, a judicial execution by guillotine was carried out in the yard of the court buildings. The victim was Dr Margarete Blank, who was forty-three. Her crime was to treat the children of an officer, to whom she expressed doubts that Germany would secure any kind of final victory. The officer reported the doctor to the Gestapo and she was arrested, tortured and falsely accused of being a member of a resistance movement. Everybody in the city knew the repercussions of a few ill-judged words to friends, family or colleagues.

None of Dresden’s inhabitants were aware that their futures were being decided in a resort on the Black Sea in Yalta. Churchill, Stalin and a visibly ill and distracted Roosevelt were discussing in detail how Germany was to be governed, following its inevitable defeat, split into four Zones of Control under the United States, Britain, the Soviet Union and bewilderingly, France. In addition the conduct of the war was being finalised with the senior Soviet military commander pointing out that Dresden would fall under the Soviet sphere of influence, that it was a strategically important transport hub and requested that the Allied strategic air forces should bomb it, in order to hamper German reinforcements to the Eastern Front.

On 6th February 1945 the US bombers attacked the towns of Chemnitz and Magdeburg, destroying their grand, civic architecture, houses and apartment buildings consumed in the fires. Magdeburg was around 140 miles north-west of Dresden and the city’s inhabitants knew it would be their turn, owing to the tiny silver dots and vapour trails of the Allied reconnaissance aircraft above them. Dresden had already suffered two previous US Eight Air Force raids, one in the autumn of 1944 and the second on 16th January 1945, killing several hundred people on each occasion.

Unknown to Dresdeners the authorities in Berlin had already designated the city as a fortress city, its defenders expected to fight and die for each block, street and building. Dresden’s population in 1945 of 650,000 was to be part of the Elbe Line, under the command of General Adolf Strauss. The Elbe Line stretched from Prague to Hamburg and the Red Army was around 60 miles away from the city. And many in the city had heard the rumours that the Soviet troops had overrun Auschwitz Concentration Camp and the horrors they had found there.

Army Map Service / Public domain

According to the RAF at the time, Dresden was Germany’s seventh-largest city and the largest remaining un-bombed built-up area. Taylor writes that an official 1942 guide to the city described it as “one of the foremost industrial locations of the Reich” and in 1944 the German Army High Command’s Weapons Office listed 127 medium-to-large factories and workshops that were supplying the army with materiel. Nonetheless, according to some historians, the contribution of Dresden to the German war effort may not have been as significant as the planners thought, but hindsight is a wonderful thing.

The US Air Force Historical Division wrote a report in response to the international concern about the bombing that remained classified until December 1978. It said that there were 110 factories and 50,000 workers in the city supporting the German war effort at the time of the raid. According to the report, there were aircraft components factories; a poison gas factory (Chemische Fabrik Goye and Company); an anti-aircraft and field gun factory (Lehman); an optical goods factory (Zeiss Ikon AG); and factories producing electrical and X-ray apparatus (Koch & Sterzel AG); gears and differentials (Saxoniswerke); and electric gauges (Gebrüder Bassler). It also said there were barracks, hutted camps, and a munitions storage depot.

The USAAF report also states that two of Dresden’s traffic routes were of military importance: north-south from Germany to Czechoslovakia, and east–west along the central European uplands. The city was at the junction of the Berlin-Prague-Vienna railway line, as well as the Munich-Breslau, and Hamburg-Leipzig lines. Colonel Harold E. Cook, a US POW held in the Friedrichstadt marshalling yard the night before the attacks, later said that “I saw with my own eyes that Dresden was an armed camp: thousands of German troops, tanks and artillery and miles of freight cars loaded with supplies supporting and transporting German logistics towards the east to meet the Russians.”

An RAF memo issued to airmen on the night of the attack gave some reasoning for the raid:

Dresden, the seventh largest city in Germany and not much smaller than Manchester is also the largest un-bombed built-up area the enemy has got. In the midst of winter with refugees pouring westward and troops to be rested, roofs are at a premium, not only to give shelter to workers, refugees, and troops alike, but to house the administrative services displaced from other areas. At one time well known for its china, Dresden has developed into an industrial city of first-class importance … The intentions of the attack are to hit the enemy where he will feel it most, behind an already partially collapsed front, to prevent the use of the city in the way of further advance, and incidentally to show the Russians when they arrive what Bomber Command can do.

In the raid, major industrial areas in the suburbs, which stretched for miles, were not targeted. According to historian Donald Miller, “the economic disruption would have been far greater had Bomber Command targeted the suburban areas where most of Dresden’s manufacturing might was concentrated.” However, suburban areas away from the river are scattered and difficult to differentiate on the H2S radar screens.

Aerial Bombing – A Brutal Reality

The German fully understood the nature of causing a fire storm by aerial bombing, a technique they had successfully employed on Coventry, but failed to do on London. The raid on Coventry reached such a new and severe level of destruction that Joseph Goebbels later used the term coventriert (“coventried”) when describing similar levels of destruction of other enemy towns. During the raid, the Germans dropped about 500 tonnes of high explosives, including 50 parachute air-mines, of which 20 were incendiary petroleum mines, and 36,000 incendiary bombs. Bomber Command used this as a tactic, particularly on German cities with a large percentage of wooden buildings.

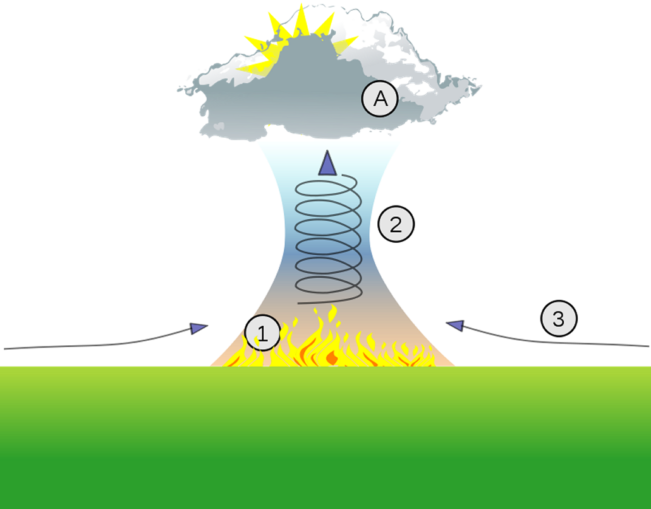

A firestorm is a conflagration which attains such intensity that it creates and sustains its own wind system. It is most commonly a natural phenomenon, created during some of the largest bushfires and wildfires. Although the term has been used to describe certain large fires, the phenomenon’s determining characteristic is a fire with its own storm-force winds from every point of the compass. Firestorms have also occurred in cities, usually due to targeted explosives, such as in the aerial fire bombings of Hamburg, Dresden, and Tokyo, and the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

In 1927 Lord Tiverton declared that: “A girl filling a shell at a factory is just as much a part of the machinery or war as the soldier who fires it.” With any weapon no matter how terrible, the impulse is always to use it. The planned German precision bombing of Rotterdam would be a precursor to a ground offensive of shock troops armed with flamethrowers. But the plans went awry and the Luftwaffe bombers scattering high explosives and incendiaries on the city, scattered pockets of fires, which rapidly grew into one, large conflagration that overwhelmed the city’s firefighters. Vast areas of Rotterdam were destroyed and the threat to use the same tactics on the city of Utrecht with its wooden framed houses and close, narrow streets was sufficient to force the Netherlands’ capitulation. The Germans truly had sowed the seeds. It was this tactic that the Luftwaffe tried to use on London and despite the widespread damage to the docks and East End, it never resulted in a firestorm such as that Coventry had suffered.

Thermal_column.svg: Dakederivative work: RicHard-59 / CC BY (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5)

By 1943 Bomber Command’s tactics had evolved from scattered packets of bombers attacking a target, to a concentrated stream of aircraft, timed to arrive over the target in a window of a few minutes. The bomber stream overwhelmed the German night fighter defences and poured a concentration of incendiary and high explosives onto the city and its population. With delayed action 4,000 lb cookies hampering the firefighting efforts, given the right atmospheric conditions and sufficient combustible material found in the wooden buildings of the German cities, a firestorm could be created.

These tactics were very successful on Lubeck and the series of raids on Hamburg during the hot summer of 1943 were hugely successful in terms of the grim reality of total war, over half of the city was destroyed and some 58.000 civilians were killed, more than twice the number that were killed in Dresden. And yet the efforts of Bomber Command in World War 2 have been defined by the single attack on Dresden. It was by studying the campaign of bombing against Hamburg that the tactic of causing a fire storm was perfected, but of course the Nazi regime never let a city’s suffering and destruction get in the way of a good propaganda coup. The inmates of Neuengamme concentration camp were force to sift through the ashes and rubble to search for the bodies, so they could be photographed and cited as an example of terror bombing.

Freeman Dyson, a young Cambridge mathematician was called up for duty in 1943 and was selected to work in Bomber Command’s Operational Research Section. He studied the effects of the seven nights and eight days of bombing of Hamburg, specifically the causes of a firestorm and the horrifying attrition rate of the bomber crews. He established that even an experienced crew had less than a 25% survival rate and were almost as likely to be consumed in a glowing, falling ball of fire as crews in their first five operations. Moreover he studied reports from pilots who had decided that the German night fighters were invisible and the suddenly exploding bombers were not due to mid-air collisions. He concluded that the Germans were using tracer-less cannons that fired from below the bombers, from the blind spot under the aircraft, out of sight of the gunners. This theory was widely disregarded and of course, the bomber aircrews were never told, although the more astute suspected that this was the case.

There was a fundamental disagreement within the Allies of the conduct of the strategic bombing offensive. The politicians such as Churchill under pressure from his US allies, had formed the opinion that specific targets such as fuel production and fighter factories should be attacked. Harris supported by Portal reasoned that the heart and soul of the Nazi regime, its population should be the targets. Harris called any deflection from his stated aim of destroying German cities “panacea” targets and was of the opinion that the USAAF claims of precision bombing were widely inaccurate and exaggerated. In any case, RAF bombers were unsuited to daylight raids, lacking the essential defensive firepower of the Eighth Air Force bombers. A criticism that could be levelled against Harris was his unshakable belief that the war could be won by attacking German cities and their inhabitants. He was considered inflexible and pig-headed, but he had moved his bombers in support of the Normandy Landings willingly enough, if not in frustration.

However, following ULTRA intercepts, Portal shifted his stance and fell in with accepted thinking that attacks on oil production and storage were more cost-effective, but Harris was not privy to higher level intelligence and was wounded by Portal’s withdrawal of support. He wrote to Portal: “The next three months will be our last opportunity to knock out the central and eastern industrial areas in Germany. Magdeburg, Leipzig, Chemnitz, Dresden, Breslau, Posen, Halle, Gotha, Weimar, Eisenach and the rest of Berlin. These places are now the mainspring of German war production and the consummation of three years’ work depends on achieving their destruction.” The next part of the letter was underlined: “It is our last chance; it would have more effect on the war than anything else.”

By 24th January 1945, Harris had stepped down from the brink of resignation but different cogs were wheeling. The Joint Intelligence Committee, the Ministry of Economic Warfare and the Air Ministry had been studying the vast numbers of refugees pouring out of the Nazi Empire’s eastern regions and the requests by the Russian at the Yalta Conference. Here was a chance to sow disruption and confusion and Harris was not the only person who regarded German lives as having little intrinsic value. Churchill was impatient to hear of the possibilities of a vast raid on these eastern cities and Air Marshal Tedder, Eisenhower’s deputy drew up a memo outlining a Joint RAF/USAAF attack on these cities. The targets were purported to be the transport infrastructure, but the results would be the same as Harris’ stated aim, the death and cremation of German civilians.

Harris received his orders with the joint RAF and USAAF raid on an as yet unnamed target, which had been on his list of German cities. It would involve a long penetration into German airspace in the short dark days and long nights of the winter. How could these young men push themselves into these long, dangerous and freezing trips again and again, knowing that the odds against their survival were increasing? Back in their bases in eastern England, these young man, American, Canadian, Polish, Commonwealth and British were unlikely arbiters of destruction and death on a huge scale. They were so unlike the swaggering automatons of the Waffen SS. They were in the main quiet, studious and calculating, fully aware of the odds being stacked against them. The best death they could hope for was the instant obliteration by an exploding cannon shell, the worst, falling through a freezing sky, burning with skin and flesh melting under a burning parachute. If they made it to the ground, they could only pray for capture by front line troops and not the summary execution of being bludgeoned to death with spades and picks, at the hands of outraged German civilians. A young volunteer, Miles Tripp who had had his tour of operations increased to thirty-five, survived the war and wrote fiction as a lightning rod to deflect from the trauma and horrors he had seen and faced. He was a man after my own heart, his reasons for writing fiction similar to my own, although I could never have faced the type of war waged by the men of Bomber Command.

But these men of Bomber Command and the Eighth Air Force were not widely admired, especially in 1945. Hostility to their waging of total war was growing from the clergy, particularly the Bishops of Chichester, Bath and Wells and the Bombing Restrictions Committee with members such as the Labour MP R. R. Stokes, the philosopher C. E. M. Joad and the actress Cybil Thorndike. There were a few who though the airmen themselves would refuse to carry out their duties, a total failure to understand that these men were motivated by more than simple duty. It is difficult to understand why these young men volunteered to serve in a duty where certain death was more likely than survival, but volunteer they did in their tens of thousands. There was a degree of romanticism involved with wheeling above the clouds in a Spitfire or Hurricane, precious little in being hunched in a tiny, freezing space for hours on end. Some men did succumb to the paralysing fear and were unable to carry on. They were interviewed by the squadron and station commanders, were stripped of rank and posted to do menial tasks at another station. Their personal documents were marked as an individual Lacking in Moral Fibre (LMF) and were disbarred from future employment in the post-war aviation industry.

On the morning of Tuesday 14th February the telex machines in operations rooms up and down the country chattered into life. The long messages gave a list of fuel loads, routes, timings, target marking flares and colours and of course bomb loads. The code word was “Usual” meaning the attack on a city target, blast and incendiary payload. The fuel load was almost at the maximum for the British Heavy bombers and the WAAFs who drove the petrol bowsers and bombs out to the dispersed bombers had good reason to believe that their young men would be flying to Berlin that night. In fact, the target would be Dresden and the young men they prayed for and looked after would be besmirched as war criminals.

References

Sinclair McKay – Dresden, The Fire and the Darkness ISBN 978-0241-98601-I

© Blown Periphery 2020

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file