November 21st, 1809 (November 9th O.S.).

Count Bagarov was delighted by our reception by the Tsar. From an obscure minor courtier lurking in the corners of the state rooms of the Winter Palace, he has advanced to being regarded as a power behind the throne, able to marshal a band of seasoned warriors and learned bears to influence royal policy – or so he believes, and we do not wish to disillusion him.

But he is still anxious to leave the court and return to his estates around Archangel. And why not? As Fred said, ‘’E knows ’ow to quit when ’e’s winnin’.’

He plans to depart tomorrow, and we shall go with him. We shall part company with Boris the bear and his human Alexey. They have decided to travel south for the winter, through Prussia and Austria, seeking the generous warmth of Italy where Fred and I spent many happy days. On Fred’s advice, Alexey is planning to enlist a she-bear to give Boris a dancing partner and companion.

We have taught them all we know about dancing, and with Alexey’s help our command of Russian is now moderate, but most importantly Boris is now a happy bear who dances for his own pleasure and that of an appreciative audience. It has been a fruitful exchange.

November 22nd, 1809 (November 10th O.S.).

This is a country without proper roads, and to travel from St Petersburg to Archangel as the northern winter tightens its grip is no easy task. It could be accomplished by sea, but that would be a slow southward voyage down the Baltic and back northwards around the whole length of Norway and the north coast of Finland; and a storm where the North Atlantic meets the Arctic Ocean is something no sensible person would wish to endure. Or we could sail up the Gulf of Bothnia to Kemi, cut across the neck of Finland to Kandalaksha, and again take ship to cross the White Sea to Archangel – but that would be a complicated and wearisome detour.

So we must go by land, on a convoy of sleighs drawn by three horses – the Russian term for this unusual arrangement is troika. The roads, barely passable in summer, are now icy tracks marked only by stakes driven into the frozen ground, and they snake circuitously between a myriad of lakes large and small, their surfaces now frozen but treacherous to venture across. The distance in a straight line is a mere 300 miles, but the road is far from straight.

Rather than skirt the western edge of Lake Ladoga, whose numerous inlets require slow ferry crossings, on our first day we have travelled north-west on a relatively straight road to Vyborg, from where we can turn north-east towards our destination. Difficult as the journey is in many ways, I have to say that the even glide of a sleigh over the snow is vastly more comfortable than the bruising jolting of a coach on the stones and potholes of an English road. The frail humans are warmly wrapped in sheepskins, and we bears ride our vehicles comfortable in our own fur and exulting in the bracing chill.

The journey is not without its hazards. As we neared our first day’s destination, a single sleigh raced by us in the opposite direction, pursued by wolves snapping at the horses, while a man desperately but all too infrequently discharged his pistol against them – is there no way of devising a method of reloading these crude weapons more quickly? It was a lucky encounter for them. When the bears leapt into the snow, most of the wolves fled with their tails between their legs. Those that did not provided us with a nutritious if stringy supper.

We passed the night in a simple inn, no worse than many in England. It is amusing to travel with a nobleman who demands the best of everything and has money to pay for it, only to find that there is little on offer. But there was plenty of the fiery Russian spirit called vodka, and the evening was a merry one with music and dancing.

November 30th, 1809 (November 18th O.S.).

We are arrived in Archangel, or Arkhangel’sk as it is properly called in Russian (the apostrophe represents the Cyrillic letter ь, which is not pronounced and merely indicates that the previous consonant should be pronounced lightly). Once an important port often visited by mainly Dutch traders, the city is sadly decayed as most Russian trade now goes through the Baltic and St Petersburg.

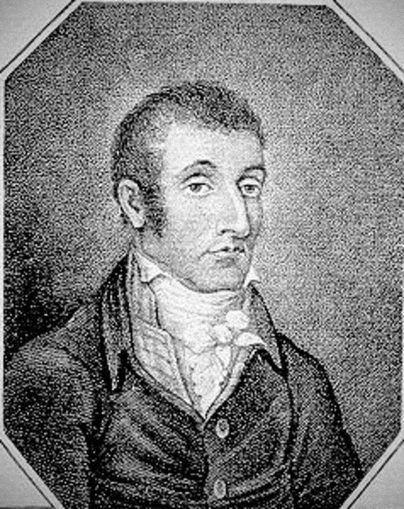

As we paused to view the prospect from the waterfront, we were approached by a thin, mean-looking man who, to our surprise, addressed us in English – no doubt he had heard us speaking in that language. He introduced himself as John Bellingham, and told us that he had recently been imprisoned in Archangel and, although now set at liberty, was forbidden to leave the city.

He then launched into a circuitous and fantastic tale of woe about a lost Russian ship called the Soleure, which he suggested had been deliberately sunk to perpetrate a fraud upon its insurers. He had, it seems, repeated this accusation to the authorities again and again until he had made himself so obnoxious to them that he had been thrown into prison to keep him quiet. He was, he claimed, destitute and starving, and implored us for help in the lengthiest and most pathetic of terms. As Appian well remarked, Αἵ τε γὰρ συμφοραὶ ποιοῦσι μακρολόγους, Calamities make great talkers.

Count Bagarov drew Fred, Jem and me aside and said, ‘Dunno wot yer fink, gents, but I reckons as ’ow this cove is a rum gagger an’ tryin’ ter rook us.’

‘Me too,’ said Fred. ‘But why are they keepin’ ’im ’ere if ’e’s such a nuisance?’

‘Tell yer wot I’ll do,’ Bagarov said. ‘I knows the mayor, ’e’s a square cove, a toppin’ feller. Fink I’ll nip in ’ere’ – he indicated a large building, evidently the city hall – ‘an’ ’ave a word wiv ’im. Yer wait fer me in that ale-’ouse over there, an’ I’ll be back in two shakes o’ a lamb’s tail.’ And off he strode. If you are a count, you do not need an appointment to speak with the mayor.

Sure enough, within half an hour, as we were enjoying some excellent Russian ale spoilt only by Bellingham’s continued whining, he returned smiling. ‘There’s a ship bound fer England in the ’arbour now, the Sara Louise,’ he said to Bellingham, ‘an’ yer on it, matey.’ So get packin’ yer bags, and never say as ’ow we didn’ ’elp yer.’

Bellingham, with effusive thanks, scuttled off to our considerable relief. Bagarov told us that he had convinced the mayor that, whatever Bellingham’s game was, he would only cause more trouble if he was detained in the city, and the wisest course of action was to get rid of him. But I fear that Archangel’s gain will be England’s loss, and that this miserable creature will cause trouble wherever he goes.

December 2nd, 1809 (November 20th O.S.).

We are now settled in Count Bagarov’s substantial and well appointed residence on the outskirts of the city, and have had our first meeting with Nikita the polar bear, for whose sake we have undertaken this long journey – though to be honest, it has been a most agreeable excursion.

Nikita is housed in the stables, and has a spacious yard in which to exercise himself. He has food aplenty and a far easier life than that of a wild bear in the barren wastes, but he is certainly not happy. When we entered his enclosure he reared up in fury, and even we were alarmed by this great white creature brandishing his formidable claws. But when he saw little Henry looking at him with the innocence of a cub, he dropped back on to all fours and allowed us to approach him. For all his difference of colour he is a bear like us, and he will soon understand that we have come to relieve his solitude and, we earnestly hope, find him a purpose in life.

Jem played his flute and we danced. Nikita was amazed. These things simply do not happen on the Arctic ice. Count Bagarov was with us, and in his countenance I saw the dawn of hope that his beloved bear will eventually find happiness in his enforced exile.

On my request, we brought Nikita into the house for dinner: a copious supply of elk for us bears, and all kinds of Frenchified fal-lals for the humans, which we did not envy. But we were happy to share their Bordeaux, a drink fit for gods and bears. At lesser times the ordinary drink here is a kind of small beer called kvass, made by fermenting stale bread. It is palatable enough but feeble stuff for those accustomed to hearty English ale.

I am writing this in the stables, to which all the bears have returned to be with Nikita. He is slightly fuddled with wine, and confused by being admitted to the house, but utterly content perhaps for the first time in his life, and has fallen asleep with his white head resting on Angelina’s brown shoulder.

December 20th, 1809 ( December 8th O.S.).

We have settled into the life of a Russian household in winter – though not the life of a wild Russian bear in winter for, having a warm place to spend our nights, we feel no need to hibernate. By day we range with Nikita in the trackless forest, often bringing down an elk for a feast. And sometimes we dine in Count Bagarov’s house, eating kulebiaka, a kind of sturgeon pie, with a knife and fork. Even Nikita has learned the use of these ridiculous implements required by a species with weak teeth and the feeblest of claws, and it amuses us to deploy them in an elegant manner. In the evenings we dance, for our own delight and that of the household.

Beneath the rituals of civilisation, we are more happy living a bear’s life, as the English members of our band are only now finding out. As Horace said, Naturam expellas furca, tamen usque recurret, You may drive out Nature with your fork, but soon enough she will come rushing back. Though he was speaking of an agricultural pitchfork rather than a table utensil unknown in his time, his words are still apt enough.

It was after one of our formal dinners, when we had all drunk deep of an excellent Georgian red wine and chased it down with aromatic Georgian brandy, that Count Bagarov felt free to disclose his secret aspiration. The company was speaking Russian, in which Fred, George and Dolores are now reasonably adept, so I will not tire your patience with an attempt to transcribe his peculiar command of English.

The count said that he had long wished to return his home city of Archangel to the prosperity it had enjoyed as a port before the foundation of St Petersburg. He believed that to do this he should not look west, to trade with the nations of south-west Europe, now well served by way of the Baltic. Rather he should look eastwards. It was known, he said, that in the summer months when the Arctic ice had receded it was possible to sail along the northern coast of Russia, eventually reaching China and Japan and, by sailing south, the wealth of the East Indies and the spice islands of the Moluccas. This route, which we in England call the North-East Passage, had never been properly explored. It was time, the Count said, to try it.

Fred was clearly taken by the idea, but he felt bound to make a few observations. First, he said, he had spoken with sailors who had ventured some way into those regions, and there was always some ice, though not necessarily impassable. It would be necessary to use a vessel of particularly strong construction to avoid its being holed and sunk by ice floes, such as a bomb ship.

‘What is a bomb ship?’ asked the Count.

This was beyond Fred’s Russian vocabulary to explain, so he reverted to English. ‘It’s a ship with big mortars for bombardin’ forts from the sea. If you fired a mortar in an ordinary ship, it’d go through the bottom. So they’re made extra thick all over.’

Second, Fred explained, even in summer it might be necessary to drive a ship at an ice sheet to break it and force a passage. With the wind in the Arctic, usually light and variable, it would be hard to do this. ‘There’s an American called Robert Fulton. ’E’s made a boat driven by a steam engine – in fact two, one in America where it’s doin’ good business on a river, and another ’e made for the French when ’e was workin’ for Napoleon. That one sank – what d’yer expect with Frenchies mannin’ it? But ’e’s shown that the thing works well enough, and you can forget about the way the wind’s blowin’.’

‘A capital idea,’ said the Count in Russian, ‘but I doubt we can tempt him to Arkhangel’sk, so we shall have to make do with what we have. At least we can try to find a bomb ship. I would like to make an expedition in spring, as soon as the ice has melted, and I hope that you will accompany me.’

‘Yes!’ said Fred and Jem and Dolores simply and in unison, and the bears roared assent.

Copyright © Tachybaptus 2019

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file

Audio Player