May 6th, 1809

We are part of a regular army again, pressing on to confront the French. I must confess that my old bones are aching from the furious pace of our advance. Jem is still limping from his injury, but we found a place for him on the tail of a quartermaster’s cart, where he is sometimes joined by Henry, our youngest bear, still only a cub and not equal to the task of keeping up a brisk trot all day.

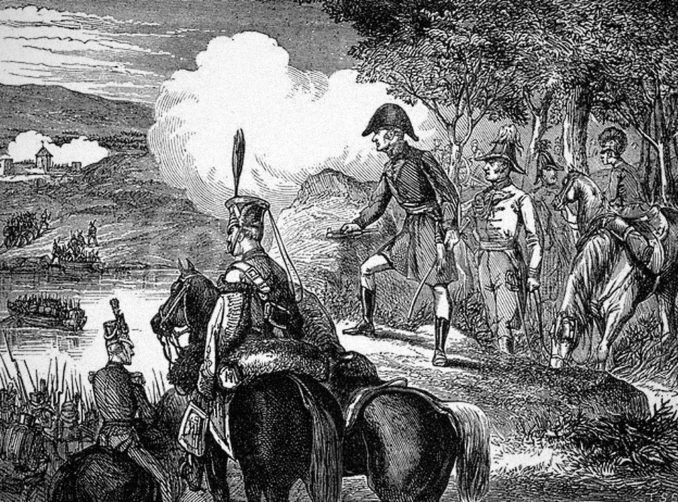

Wellesley’s force is a patchwork affair including two hastily formed Battalions of Detachments, made up from scraps of various regiments disorganised by the evacuation from Corunna. But they have come together into a formidable force and Wellesley, a natural leader to whom his men are devoted, will deploy them with all the considerable skill at his disposal.

Our accidental choice of this cart has proved most fortunate. It seems that the arms include a stock of Jäger rifles captured from the French in some earlier encounter. The British riflemen have their Bakers, so our Portuguese irregulars, most of whom are armed only with muskets, can have their pick of them.

At a brief halt – too brief for this bear! – we inspected the store and the men chose their weapons. Some of them are hunting rifles, shorter in the barrel for easy carrying but still accurate enough. Little João, barely four and a half feet tall, took one of these, a beautiful thing with a carved walnut stock bearing a silver plate with a coat of arms that includes a double-headed eagle. Who knows what deceased German nobleman yielded his weapon to the French invader? But now it is again pointing in the right direction.

Yesterday evening Jem and Fred, aided by those who already possessed rifles, drilled the new owners in the intricate procedure for loading them. It is easy to forget to slide in the safety catch at the rear of the lock when it is at half-cock and you are putting powder in the priming pan, and there was one accidental discharge in which fortunately no one was hurt; at least it reminded them to be more careful. Flints are a constant problem, striking fine sparks until you actually need one, at which point they inexplicably stop working. Fortunately we have a few spare flints already shaped for use.

May 9th, 1809.

We are encamped near the village of Grijó, and our scouts tell us that the French are just over the hill. Wellesley conferred with his officers, and by the courtesy of war that includes Fred, as leader of the Portuguese sharpshooters, and myself, as leader of the bear force. Fred is to take to the hills and harry any French advance; we are to stand ready to panic the horses in any cavalry charge. We were delighted to see Paget again, beside whom we had routed the French at Sahagún. And Wellesley, who has only 35 riflemen from the famous 95th Foot, is pleased to have a further 25 Portuguese riflemen, their sharpshooting skills polished by collecting game for the pot on our travels.

May 10th, 1809.

So far the engagement has been inconclusive. The splendidly dressed Major General Stapleton Cotton, known to his men as ‘Lion d’Or’, displayed his golden frogs to the Froggies and they hastily fell back upon the village. We have not been in action.

May 11th, 1809.

Battle was joined in earnest today. We bears were with Paget’s cavalry, ready to repel any French cavalry. The English horses are used to us, many of them remembering us from Sahagún, and we have been accustoming the others to bears by ambling peaceably among the lines. We met the French in the early afternoon, and our charge from the wooded sides of the valley had its effect. But it was a stiff engagement and there are many casualties among the men – though I am selfishly glad to say that the bears received only a few scratches. In the heat of action guns are aimed at people: they forget us.

Later, Wellesley sent the King’s German Legion to attack the French on one flank and the 16th Portuguese to take on the other, while he advanced on the village of Grijó. The French withdrew to the wooded hillsides, and it was the devil’s own task for our motley collection of riflemen to take them out one at at time. But by nightfall we had dealt with them well enough, and the survivors withdrew.

Our Portuguese irregulars, thankfully unscathed, were ecstatic at their success, and bears and men danced around together to the music of Jem’s flute. They have lost what little they had in this bitter war, and any advance is cause enough to rejoice. As Seneca says,

Minus in parvis Fortuna furit,

Leviusque ferit leviora Deus.

‘Fortune is less harsh on the humble, and God strikes the weak more lightly.’

May 12th, 1809.

Fred said to me, ‘That Wellesley cove, ’e don’t ’ang abaht.’ Never were words more truly spoken. Fresh from our victory at Grijó, the General pressed directly onward to Porto.

At once we met a serious obstacle: the Douro river, wide here where it is about to discharge into the sea. In falling back on Porto, Soult had of course taken the boats to the north side, so there was no way for our men to cross. We found just three which they had missed, not enough to transport our force in good time.

Bears came to the rescue again. Rummaging around the quays on our side, the men found enough rope to span the river, and under cover of darkness we swam across with the end and tied it to a barge, which we quietly unmoored so that it could be hauled back across the water. Our lessons in knots on the ship that took us to Lisbon have served us well. We captured half a dozen barges in this way while the sentries dozed, lulled into incaution by being on the far side of the river.

May 13th, 1809.

Porto is ours, after a brief but furious action. As soon as our forces began to arrive on the north side of the river and take on the French, intrepid Portuguese civilians came to our aid, launching every boat at their disposal to ferry the rest of the men across.

Wellesley captured a seminary on the north bank and used it as a base, to the confusion of the young clerics living there, whom Jem sent to the cellar with a shout of Todos vocês, fiquem lá embaixo e mantenham a cabeça baixa – ‘You lot, stay down there and keep your head down’ – which may not be good Portuguese but had the desired effect.

The action was mostly hand-to-hand fighting in the streets in which bears armed with cutlasses played a not inglorious part. But the French still had some artillery, and it was trained on our temporary headquarters.

And here there occurred one of those turns of Fate on which wars hang. Standing next to Wellesley and looking over the town, I saw a cannon surrounded by French troops and pointed straight in our direction. Fred and Jem and his men were off in the town, and there was no way of taking out the gun crew. There was a puff of smoke. Usually, when a cannonball is fired, it goes too quickly to be seen, but when it is coming straight towards you it is perfectly visible. The rising ball began to descend, and it was clear that we were in its path. I flung myself on Wellesley and bore him to the floor as the sound of the shot reached us, followed an instant later by the ball, which entered the open window and smashed a hole in the wall directly behind where we had been.

Wellesley had just the time to shout ‘Damned bear …!’ before he saw what had happened, and then he embraced me with a cry of ‘Daisy, my dear, by God you’ve done it again!’ We were both covered with plaster dust and, as I discovered later, I was bleeding from many small wounds caused by stone chips from the wall.

I believe that Wellesley is protected by a vigilant guardian angel, or maybe a devil, which at this moment acted through me, and that he will pass through this war unscathed and victorious, and live to a great age loaded with deserved honours.

May 14, 1809.

In the aftermath of a victory joy is mixed with sorrow. The bears attended the burial of the dead, and accompanied Wellesley as he visited the wounded. We raised their spirits, as they consider us bringers of good fortune.

There was a dinner for the officers, and Jem, Fred and myself, as leaders of our motley band, were graciously considered as such. Fred, though he has spent his life on the road, is one of nature’s gentlemen and can behave appropriately at such occasions, and Jem has learnt the ropes in his life as a manservant. As for myself, I can hold a knife and fork and eat slices of roast mule with the best of them, though to my mind it is tastier served raw and on the bone, and tackled with tooth and claw.

The quartermaster had found a few dozen bottles of port in a fortuitously unlooted corner of the aptly named Warre’s port factory – the term used for a warehouse of this noble beverage which is Portugal’s principal and best loved export to England. The rest of their year’s stock, 3000 pipes of port, had not survived the first visit of our army and later looting by the French. We toasted our victory and drank the health of our gallant allies.

Wellesley asked Fred how it was that he was in command of a company of bears. So Fred and Jem, their tongues loosened by copious draughts, alternately told the story of how we came to be in Portugal. At the mention of Lord Byron, Wellesley’s lip curled: ‘That scribbling scoundrel,’ he said. And when Jem confessed that, not having been paid for more than a year, he had taken his payment in kind from Byron’s silverware, the company applauded. Soldiers understand the unspoken rules of war.

Inevitably, the subject came up of how I was able to get Byron his degree. ‘Do you mean to say,’ asked Wellesley, ‘that this bear understands Latin and Greek well enough to satisfy the examiners of a famous university?’ I was embarrassed, because this is an accomplishment best kept concealed from public view – but we were among brother officers, and there is a time for the truth. I motioned to Fred, who passed me the school slate and chalk that we use when I have something to tell him.

But what to write, for a band of humans who have been to the best schools, but probably retain, as Ben Jonson said of Shakespeare, ‘small Latin and less Greek’? There are three passages that anyone who has studied ancient Greek for more than a moment will recognise: the first few lines of the Iliad and the Odyssey, and the first few verses of St John’s Gospel.

The Iliad I discounted: the sad tale of a vain hero who, in a fit of pique over a girl, sulks in his tent and brings disaster on his army. St John’s elegant words seemed a little too theological for a company of soldiers in their cups. So it was the Odyssey, and with not a little sentiment of our own situation I wrote:

Ἄνδρα μοι ἔννεπε, μοῦσα, πολύτροπον, ὃς μάλα πολλὰ

πλάγχθη, ἐπεὶ Τροίης ἱερὸν πτολίεθρον ἔπερσεν·

πολλῶν δ’ ἀνθρώπων ἴδεν ἄστεα καὶ νόον ἔγνω,

πολλὰ δ’ ὅ γ’ ἐν πόντῳ πάθεν ἄλγεα ὃν κατὰ θυμόν,

ἀρνύμενος ἥν τε ψυχὴν καὶ νόστον ἑταίρων.

‘Tell me, Muse, of the versatile man, who wandered far and wide when he had sacked the sacred citadel of Troy: many were the men whose cities he saw and whose mind he learned, and many the pains he suffered in his heart on the sea, seeking to win his own life and the return of his comrades.’

The men were dumbfounded, though probably half of them could have managed as much themselves. Wellesley said to Fred, ‘So, sir, is it truly your own shore you seek again?’ (He had never called Fred ‘sir’ before, but it was now a conversation between equals.)

‘Sir,’ said Fred, ‘we didn’t come ’ere to go to war, we was just on the run. Reckon the war found us, like. But we done all right, to my mind. We fought our fights, we raised a little band o’ guerrilleros, an’ they done us proud. But we ain’t fightin’ men – nor bears – no way. Reckon this is a proper stand-up war now, an’ we ain’t got no part in it no longer.’

‘It is true,’ Wellesley replied. ‘You and your bears and your Portuguese riflemen have served us well, and you have more than earned your passage home, and you two and the bears shall have it. And a letter from me to the chief magistrate of the Runners will halt their pursuit of you. As for the riflemen, I have news. They are to be returned to the Portuguese army – not to their original regiments, but to a new corps of sharpshooters, and all of them shall be promoted to corporal and set to train new recruits. I did not want to tell you this lest you should think we were poaching them from you, but as things have turned out it is for the best.’

All cheered, but none louder than Fred, Jem and myself.

Copyright © Tachybaptus 2019

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file