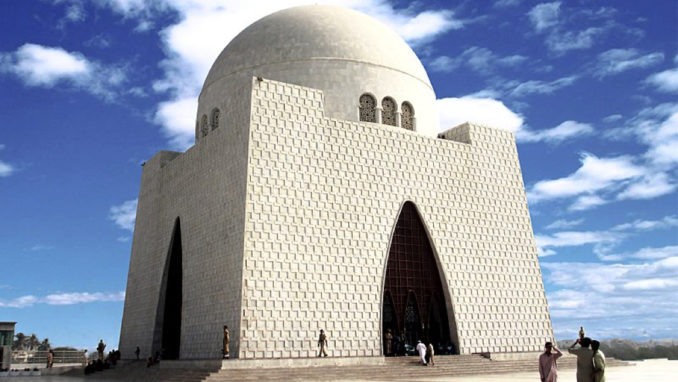

Jinnah’s Tomb, Shahid Siddiqi – Licence CC BY-SA 4.0

You may wonder, dear reader, after ten episodes and a prologue, where all this is leading. It certainly doesn’t seem to be leading to Lille. Bear with me. You’ll recall that, for obvious reasons, the first of Ovid’s metamorphoses was from absence to substance, nothingness to some thingness, chaos to cosmos, as God in the first verses of the Bible separates light from darkness. Echo couldn’t flee from Narcissus like a light wind before the pair of them existed.

You will have also have noticed your author as nothing but a young single man on the move, subsequently transformed to nothing beyond that family man, on that train to Lille, reflecting.

The drunkenness of youth always passes like a fever and in my case that fever lifted very quickly indeed, at a kerbside, on a very bad day in the tropics.

Bear with me even longer as there’s something I forgot to tell you. Regular readers will recall the Brigadier General in charge of lost property at Karachi airport. He is pivotal to what happens next despite a separation of many years and thousands of miles.

I was introduced to him after leaving my socks and shoes on an aircraft at Karachi airport. He was jolly chap, looked like a Pakistani Jeremy Paxman and was an English boarding school and university anglophile. After re-uniting me with my lost property and giving me a cut of the duty free cigarettes left behind on the plane, he walked me back through the airport, which in those days was a warren of corridors connecting a hotchpotch of concrete box buildings.

‘Do me a favour old chap’, he said leading me into an office and opening a draw, ‘put these up for the night.’

He handed me a pile of passports, the stranded transit passengers.

They were scattered about the airport but didn’t take too much finding. I had their passports remember, complete with a photo. None of them were Pakistani, obviously, therefor in those days I was looking for the only eight people in Karachi airport who didn’t have brown hair, back eyes, or Mohammed somewhere on their birth certificate. I found them in ones and twos, in good time. Relieved to see somebody (and their passports) they followed me around in a pack. With one more left to find I stood on a chair and kept on yelling ‘John’ until he found me. John was a teacher on his way to teach English in Japan. There were two Malay merchant seamen on their way home who swore they’d met me before in a place called ‘The Blue Monkey Club’ in a place called ‘Middlesborough’. I ask you. Two very shady characters heading to a non-extradition country in south east Asia, an elderly gentleman going to meet his Thai bride and a Filipino woman who, like a hag in a Shakespeare play, held me by the arm and prophetically chanted, ‘Never go south of Cebu’.

We trooped out of the airport without a hint of a clue of a plan. They say that if all else fails just stand and do nothing until something crops up. They are of course correct. The Brigadier General’s habitual sloth had created a well worn opportunity in the routine of the day and, in no time, boys were offering to find busses to take the stranded transit passengers to a transit hotel.

We chose a little mini bus with some natives on board who presumably didn’t mind a detour. Karachi is one of those places where the ladies sit at the front and cover their eyes and overt their gaze as the gentlemen pass to the back.

There was a bit of a scuffle and some screaming as the unknowing gentlemen transit passengers wanted to sit at the front too. Local rules were applied and order was restored. Your author is a very shy, slightly built, anonymous looking chap who might be expected to lose every fight. Having said that, one firm confident arm on an elbow and another on a shoulder, combined with a big loud voice and a good hard shove, never fails. And it helps when your average Malay sailor is four foot nine.

When the driver asked for money I decided the rule was that the hotel would pay. When he argued I told him that the hotel would pay double. So off we set.

Now, dear reader, I wasn’t in transit and frankly had other things to do. But then again, why not? I certainly had those passports in a vice like, white knuckle, grip and wasn’t going to let go until they were being put in a safe.

Off we thundered towards the streets of Karachi. We passed some bleached open ground and bounced over a railway line which appeared to be going from nowhere to nowhere watched over by a single semaphore signal. I do have a family connection with Pakistan with my grandfather having served in the North West Frontier Territory and my great grandfather in Waziristan. Crossing the line I couldn’t help but stretch my imagination to a disembarkation at Karachi docks, all those years ago, and a train journey up country on the very rails I was now crossing. It was a very long stretch of a young man’s over active imagination but you never know. I also resolved to go up country myself, deep into bandit territory, and re-trace their steps. A tale beyond fraught which must be saved for another time.

Having cleared the rough ground the brakes went on with a vengeance as we hit Karachi proper with its jungle of concrete blocks and sclerotic traffic. Or at least they should have given the congestion of cars, buses, jeeps, people, stalls and all manner of things animate and inanimate blocking the way. Instead we just carried on at full speed swerving, avoiding and colliding in fairly equal measures.

I must pause at this point to mention the heat. It was beyond boily, sticky, sweaty hot. It was hotter than an oven, turned up to full heat, on fire, whilst sat on the surface of the sun. And being surrounded by concrete and car fumes made it even hotter.

Being a hill and lake kind of chap, from the northern most part of our mellow country, I not only thought that I was going to die but that I already had and God, having pondered on sending me to hell, had subsequently decided to send me somewhere ten times hotter.

And if anybody tells you that they know Karachi, they don’t. It isn’t knowable. I suspect the locals navigate by instinct like homing pigeons. Or just drive round and round, like Dante’s adulterers, until they bump into whatever they were looking for. That might also explain the traffic.

There is no middle or suburbs or environs just endless nondescript blocks of concrete buildings packed with people and vehicles. There isn’t a castle and a cathedral and a street of shops and then something else. Just an endless sprawl. If you insist upon dividing it into quarters then there’s only one giant quarter stretching from horizon to horizon and it’s called the ‘Concrete Quarter’.

Then we stopped dead at the Transit Hotel which resulted in another scuffle past the ladies and another argument with the driver over money during which, unusually for me, I parted with a dollar bill and told him the hotel would pay him the rest.

Beyond the wire and armed guards, reception didn’t seem too surprised to see us and started passing out room keys. I handed over the passports to be put in the safe riposting,

‘Make sure they get back to the airport tomorrow, old chap’, while turning to sprint back to the bus.

But fatally I lingered, the serotonin was high, the Sirens were calling for me to stay, the little voice telling me to run was easily ignored, so I asked if there was a free feed in this for me. There certainly was and a wallah, in a spotless white jacket, led me through the compound to the restaurant.

This was a large room with a veranda along one side which opened up onto a grassed area dotted with some cabin rooms. It was full of round tables beneath slowly spinning white fans. It was busy, full and noisy.

Now I wasn’t, then or now, totally familiar with local custom but did suspect I’d been led into a wedding. A waiter certainly sat me next to a girl decorated as a bride looking like a princess from the most expensive Bollywood film ever.

I exchanged a few pleasantries with her and was bit disappointed (having assumed that the only three intrepid travellers ever to reach that place from the old country were myself, John the teacher, and the Thai bride OAP) to discover that she was a schoolgirl from Wolverhampton with a very thick black country accent. Her father, a taxi driver, sat beside her, suffering in a heavy suit in the heat, and would say nothing. The wedding fare wasn’t great. In Pakistan I lived on fried eggs, yogurt, small portions of rice and soggy pastries with something inside that didn’t have a name. And so it continued at the wedding.

Karachi Skyline, Nomi 887 – Licence CC BY-SA 4.0

I began to attract waiters with foreign currency queries. It goes with the job. Any odd currency of any denomination can be used to fob off Karachi hotel staff. Don’t be dismissive. I was occasionally in Eastern Europe myself so gave a reasonable rate for Forints (how the hell did they did they find their way to Pakistan during the Cold War?). There was a certain amount of kudos back in our compound in making oneself useful. And small amounts of lower denomination currency from obscure parts of the world could be a godsend as colleagues tended to be sent off all over the place at the drop of a hat . A bit of a queue built up as staff tried to turn stingy tips into dollars. I’m sure some of it wasn’t money. You used to get little vouchers in cigarette packets in those days and I think some lucky chaps got a few dollars hard currency, to spend at the import cash and carry, in return for some.

Likewise, raiding the safe at the compound, some poor soul of a colleague will have headed off to an exotic location, dreaming of a five star hotel, only to end up living in a hostel and slowly starving to death on five Benson & Hedges coupons a day.

Fortified with a little wallet of notes and a half full stomach I made my excuses and offered my best wishes to the bride.

I strode back through reception ignoring the staff and security and headed to the front of a little row of taxis on the opposite side of the street.

I enquired about a ride to Jinnah’s Mausoleum, a destination that would invite little suspicion. Our compound was close by and I would expect to slip through the crowds and find it on foot, which was doable if not 100% safe.

Ashmet the taxi driver also had a plan, and I considered it a better one. He would take me to Jinnah’s Mausoleum for free, if he could take me shopping first. Obliviously I’d buy a few necessities and little trinkets and Ashmet would get a cut from the shop keeper. I might even find one or two nice pieces for little gifts at a fraction of the cost in the west and a free ride to within five minutes of our compound. Deal done.

What I didnt realise was that “shopping” meant visiting a warehouse in a difficult part of the city, near the docks, in an Aladdin’s cave of goods smuggled from over the border in Afghanistan in what can only be described as a ‘Mujahideen Cash and Carry’. Not only that, but a very important, exceptionally tall chap, with a beard and kidney trouble, from head office in Kandahar, was in town and at that very moment stacking the shelves with five of his wives.

To be continued ……

© Always Worth Saying 2019

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file