March 2nd, 1809.

We are back in Portugal at last. It has been a circuitous journey across ridges and valleys, avoiding the French troops on the lower ground, but we have managed it without any serious encounters. Angelina’s wound is fully healed and she is marching with the best of us.

The frontier is marked by the river Minho, or Miño as it is spelt on the Spanish side. We crossed it as far to the east, and therefore upstream, as we could, but it is still a substantial and fast flowing river. That presented no problem to us bears, of course: we could swim across a turbulent river twenty times as wide without turning a hair. But it was not only bears who needed to cross. Jem and Fred can both swim, in a slow and clumsy human fashion – I can hardly believe that humans actually have to be taught to perform this simple act, and drown for not knowing it.

However, as a military expedition we have our baggage, including a stock of precious gunpowder which simply cannot be allowed to become wet. The two Baker rifles, delicate weapons, must also be protected. We do not possess oilskin wrappings to keep things dry.

Therefore, when we contemplated the crossing, we had to find a way of keeping these fragile things above the water. Luckily for us (but sadly not for others) we found the ruins of a farmhouse from which we were able to extract enough charred beams to make a raft.

So we crossed, with the raft propelled southwards by strongly swimming bears, and arrived at the farther shore a few hundred yards west of our starting point with all our powder dry and, as Fred says, ‘everything shipshape and Bristol fashion’. I have been to Bristol, and its fashion is not one I would wish to follow, but let that pass.

On the subject of looking after those rifles, let me mention that we have had difficulty finding a suitable gun oil to keep the bores clean and the locks working smoothly. The only oil commonly available is olive oil, which soon turns to a thick slimy paste and can ruin a weapon in days. We captured a small bottle of spermaceti oil in our raid on the Spanish armoury last month, and Jem has been using it as sparingly as possible, but it will not last much longer.

March 4th, 1809.

Crossing the frontier has hardly brought our band into a place of greater safety. Here too Soult’s troops scour the land. Queen Maria and the Prince Regent João have fled to Brazil, as has the entire government, leaving their people at the mercy of the French invaders, and it is up to us to look after the folk that these scoundrels swore to protect.

March 12th, 1809.

As we proceed, we have collected a ragged host of Portuguese infantrymen scattered by recent routs. They have been scraping a starving existence in a hard countryside in cruelly cold weather, as indeed we have, but we are better adapted to such conditions. Loyal to their country, they long to take reprisals on the invaders, but they are unarmed, and their training has not prepared them for the warfare of the guerrilla.

Fred and Jem have been taking counsel, and have decided that we must risk another raid on an armoury. We had the devil’s luck in our earlier attempt – can we pull it off again? We hear that there is a suitable place only a few miles away, in a commandeered farmhouse a good distance from any town or village. Although we cannot take our unarmed and disorganised Portuguese allies into such an action, we can use them as spies, and so devise the best plan of attack.

March 14th, 1809.

I am writing this with a happy heart – but not with unmixed happiness, as dear Jem has taken a pistol ball in the calf. Fortunately the ball passed through, and we seem to have evaded infection with one of my thyme poultices; but for the moment he cannot walk, and my son Bruin, the noblest of bears, has laid aside his dignity and is willingly playing the role of a horse to carry him about. Jem is stoical and laughs at his misfortune: he would make a good bear.

But to return to the story, we attacked the armoury, as before in the small hours of the morning when we expected the guards to be least alert. A silent charge of bears instantly overwhelmed the outside sentries, and we were into the building in moments. A few men inside were still awake, though drunk, and it was when we were dealing with them that Jem was wounded by a chance unaimed shot. However, we despatched the lot of them, and assessed our booty.

The greatest treasure was six German Jäger rifles, fine weapons though cumbrously long in the barrel. We found a store of balls for them ready cast, with moulds to make more, so if we can train our new allies in their use we have the germ of a little Rifle Brigade.

Aside from that there were muskets, pistols, balls and powder aplenty, as well as swords, daggers and supplies of food and wine. There was even a store of boots, of which our ragged allies stand in sore need. We called them in from where they had been waiting in the bushes and dragged our spoils away, then as before demolished the building with the remaining gunpowder. We earnestly hope that by leaving no survivors, and no trace of our presence, we can as far as possible avoid French reprisals on civilians, the dreadful price of guerrilla operations. But in this we can never been certain, as the grim history of the war in Spain shows all too clearly. A raid on a town may seem successful at the time, but too often it proves to be what Herodotus called καδμεία νίκη, a Cadmean victory, in which the conquerors suffer more than the conquered.

March 20th, 1809.

We have now begun the task of forming our motley collection of Portuguese irregulars into a corps of sharpshooters. Trained as line infantry, they know nothing whatever of such skills, and it has to be admitted that we know only a little more; but what we do know comes from our time with the Spanish guerrilleros, and they are folk to be reckoned with.

Our first task was to retire to a secluded valley where shots would not be heard, and to find which of the men were the best marksmen; we would award our captured rifles to these. It is not easy to hit a target with a musket, a most inaccurate weapon and almost useless beyond the distance to which one could throw a stone, but by dint of repeated firing were were able to single out those who achieved the most consistent results. We had, and still have, plenty of powder and can afford to be thorough in our trials.

We then had to instruct our chosen men in the art of loading a rifle, a harder task than for a simple musket. The charge has to be measured with greater care, and ramming the ball down the barrel, wrapped in thin greased parchment for a better fit, takes time and strength and sometimes the use of a mallet to force the ramrod in. To achieve two shots in a minute requires considerable training. But, in the words of Epicharmus, τῶν πόνων πωλοῦσιν ἡμιν πάντα τἀγαθι θεοί, the gods sell us good things for hard work.

March 30th, 1809.

We hear encouraging news from the north: the Spanish have rallied and defeated the French at Vigo. Let us hope that the tide is turning in our favour.

Meanwhile, we now have the beginnings of a fighting force. Our men are showing promise as irregulars, as they probably never did as regular troops. They are peasants who know their own territory, and can move across it with ease and freedom. They needed some training in the art of finding a good firing position, not to mention in not shooting each other by mistake, as has nearly happened a couple of times, especially as we are obliged to place all those armed with muskets at the front of any advance, since their weapons are useless at a distance.

April 5th, 1809.

Ill tidings: at Porto to the west, Portuguese resistance has collapsed and Soult now commands this vital port, where he has captured a vast amount of ammunition and supplies. Our men are angry and thirsting for revenge, but what can a couple of dozen men, even with the aid of nine mighty bears, accomplish against the might of the French army?

It would be safer to continue our training and avoid contact with the enemy, but we must let the men put their new skills to the test. With the country again in chaos, we can allow ourselves a direct confrontation with less risk of reprisals against the civilian population. So we are planning another raid on a French detachment, which if successful will both replenish our supplies and keep up the spirits of our little force. Ἐλπὶς γὰρ ἡ βόσκουσα τοὺς πολλοὺς βροτῶν, it is hope that maintains most of mankind, as Euripides wrote.

April 7th, 1809.

Our raid has been successful, but not without cost. Manuel, one of our musketmen, is dead, and two others have slight wounds. Bruin had his scalp grazed by a bullet. As scalp wounds do, it bled profusely, and my mother’s heart was wrung as I saw his dear face streaming with blood. But he will be as right as rain in a couple of days.

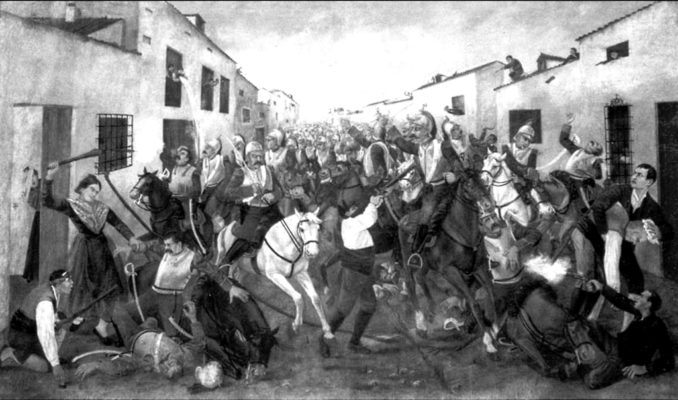

We waited by a roadside for a French party of manageable size to pass, and at dusk saw a force of about forty artillerymen, with mules dragging five field guns and their limbers. Accurate fire from the rocky hillside sent the mules into panic and they bolted, soon overturning the gun carriages and limbers on the rocky road. Taking advantage of surprise we fell on the men, and there was a brisk exchange of fire followed by a frantic pause to reload, during which we bears accounted for many of the French, and the Portuguese despatched others with swords and daggers. In the next burst of fire our riflemen could do nothing, as foe and friend were mixed together. Driven by fury, we prevailed.

We mourn our loss. But as for the French, our band threw them all over a cliff and, in the words of the Iliad, αὐτοὺς δὲ ἑλώρια τεῦχε κύνεσσιν / οἰωνοῖσί τε πᾶσι, made them spoils for dogs and every bird. However, I must stop quoting the classics, however splendid the poetry. We are not at a little siege of a town in Asia Minor; we confront a tyrant whose intention is to swallow up the whole of Europe into his monstrous empire.

One of the mules had a broken leg. We killed it for a stringy dinner. The remainder we freed: they were probably stolen from the local people, who may find them again. Our supplies are replenished and, thanks to the artillerymen, we have as much powder as we can carry. We intend to continue our journey south to Lisbon. With the northern port in French hands, the returning British forces will be obliged to land there.

Before we left, we buried poor Manuel. One of the men has a little education and was able to mumble a few Latin words of the burial service over his grave. We left it with a sad little wooden cross which wind and rain will bring down in a year. Such are the fortunes of war.

May 2nd, 1809.

At last the British have returned to Portugal. On our journey south one of our bear scouts reported a force in unfamiliar uniforms marching towards us. Jem went out with him and returned in high spirits, shouting ‘It’s the Redcoats!’ I should explain that this colour ‘red’ is something that we bears do not experience. We can see yellow, green, blue and violet well enough, and can tell the green jacket of an English rifleman from the blue French uniform, but with the red of British forces we are at a disadvantage.

After some discussion, we decided that Fred and Jem should smarten themselves up as far as is possible when one has spent months living in the open, leave their weapons behind, and report to the British officer in charge of the detachment. Wherever they are going, they are our allies and we are in a position to help them, if only in small way.

May 3rd, 1809.

Excellent news: Sir Arthur Wellesley has returned and is marching north to confront Soult – and we are of the party. Fred and Jem duly presented themselves. Despite their villainous appearance, all they had to do was to utter a few swearwords to prove themselves English, and they were ushered into the presence of the general himself, where they told their story.

Wellesley had heard of our prowess at Sahagún, of course. It was the talk of every officer’s mess for weeks, a battle saved by bears. He laughed delightedly, but not scornfully, at our little offer of help, and sent Jem to bring us for his inspection. We lined up in front of him, twenty-five shaggy bandits and nine shaggier bears, and saluted as smartly as we were able. Wellesley contemplated us with an elegantly raised eyebrow. ‘I don’t know if they’ll frighten the enemy,’ he said, ‘but by God they frighten me.’

Copyright © Tachybaptus 2019

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file