December 25th, 1810.

We celebrate our first Christmas at sea – or at least, the English humans and bears of our party do, for the Russian crew prefer to wait until their laggard calendar produces the feast on January 6th.

There is no dissension about this, as both parties are happy to have two festivals with as good a meal as can be provided at sea, and an extra rum ration to wash it down. It is also little Aeolus’ first Christmas, though at barely two months old he is unaware of it. His hair is beginning to grow, and it is the same flaming red as his mother’s.

It was a happy and convivial day interspersed with the daily routine of our voyage, now so familiar that we barely notice our duties and watches. Dolores intervened with the Russian cook to produce an acceptable plum pudding, which was served flaming with rum to the delight of all the crew. We remember our last Christmas, or Christmases, amid the luxurious hospitality of Count Bagarov – but here we are, still with the Count and on his own ship, and all present with the addition of one bear and one human baby, welcome visitors indeed.

We do not intend to make landfall until we reach the Cape of Good Hope, and will take an easterly course that will keep us well clear of the island of Madagascar. When sailing down the east coast of Africa it is advisable to stay well clear of the land, as the prevailing east winds have driven many a ship ashore and the coast is littered with wrecks. The region is also infested with pirates – not that we have any fear of them with our crew of bears, but tangling with them would only bring pointless delay and exertion.

Our intended course will take us past the Chagos islands and Mauritius, both in French hands. As far as we know, France and Russia are still allies in name, but we are unwilling to put that to the proof and will steer clear of them. On the advice of Misha, the only member of the crew who has sailed in these waters, we will also do well to avoid Madagascar which, he says, is visited only by pirates and slavers. He told us of a French gentleman who came to the island to study its fauna, which include the mysterious lemurs found only here. He vanished into the interior and was never heard of again.

January 1st, 1811.

We celebrate the New Year by crossing the Equator yet again, southbound for the Cape. Little Aeolus has now crossed the line three times and must be getting used to it. The rest of us drank to the continued success of our voyage in rum. And, now I think of it, so did Aeolus, at second hand from Dolores. He sleeps well and is mostly cheerful when awake, all that one could expect in one so young.

January 6th, 1811.

Today, of course, is 25th December in the old calendar, and our second Christmas. It is good to have these continuing festivities to punctuate the tedium of a long voyage. Count Bagarov made a long speech in Russian which was cheered by all, but I cannot recollect what it was about.

January 13th, 1811.

The last of our feasts at the turn of the seasons, the Russian New Year – not so new for the English members of the crew, but another cause for celebration. And there is another reason to celebrate: Beaivi is due to bear a cub. The voyage has thrown the customary seasons of polar bears askew, but we expect a birth early in May, by which time we hope to be in whatever part of Europe Fate takes us to.

February 1st, 1811.

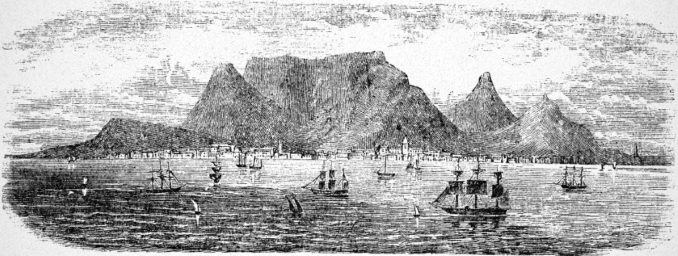

After reaching the safe latitude of 32 degrees south we have been able to turn west without the risk of being driven ashore on the barren African coast. This afternoon, to our relief, we sighted land in the distance, and with a fair wind we should reach Cape Town tomorrow.

February 2nd, 1811.

As we approached Cape Town from the east we saw a vessel approaching from the west, evidently heading for the same port. After some hours we could discern the fine lines of a Royal Navy frigate in full sail, tacking into the east wind while our slower craft was coasting in, so that we arrived at the same time. It was clear from the telescopes pointed at us that they were curious about what was obviously a naval vessel flying the Russian flag (but not the Russian naval ensign) so far from her home.

We sailed side by side into the harbour, within hailing distance. The captain of the other ship introduced himself: Sextus Whimbrel, of H.M.S. Intolerable, on his way from London to Bombay.

The Count leaned over the taffrail and raised his megaphone: ‘Cheerio, me deario, an’ I’m Count Bagarov o’ the good ship Dronning Bengjerd. In the nime o’ ’is Imperial Majesty, Emperor o’ all the Russias, we bin on a voyage o’ exploration, an’ we gone through the Norf-East Passage – nah we’re ’omeward bahnd the long way.’

We were close enough to see from the reaction of the captain and the men around him that we were not believed, and my acute ears caught one of the British seamen muttering ‘Pull the other one, it’s got bloody bells on it.’ It was not just the improbability of our story of a voyage never before achieved: the Count’s villainous accent and, it has to be said, his name when pronounced in the correct Russian manner, were detrimental to belief.

This was the first time that we realised that our tale might be incredible. The astute Stamford Raffles in Batavia had accepted it without demur, but then we were still quite far to the east and the notion of our having emerged from the Bering Strait seemed likely enough. Whether we are believed or not, others will make the voyage later. Echoing Horace, I say Credite posteri, Believe me, ye who come after.

As we dropped anchor side by side in the harbour of Cape Town, and our well drilled band of bears furled the topsails a good two minutes more quickly than the British sailors could achieve – and in particular, as two huge polar bears could be seen on deck hauling in the clewlines – we sensed a growing respect from the other party.

Before the harbourmaster’s boat headed towards us, bringing the usual tiresome requests for dues and chores, the Count had invited Captain Whimbrel aboard to take a glass of wine with him. In the event it was three bottles of claret, almost the last of our cellar, but they were well invested, for by the time the captain clambered a shade unsteadily down the rope ladder to return to his own vessel our tale was fully believed and our exploits acclaimed.

However, I fear we shall face further incredulity in the future.

The captain brought us news of our old friend Sir Arthur Wellesley. He is now Viscount Wellington, apparently taking his title from a small town in Somerset with which, as far as any of us knew, he has no connection, but it has a fine sound. I once performed there in the old days of touring with Fred, and it was a sleepy little spot. The Viscount has been giving the French a hard pounding in Spain and Portugal, but the affair is by no means settled yet.

February 4th, 1811.

On our travels we have visited places that were administered by the British East India Company, but the Cape Province is under direct British rule, having been taken over from the Dutch in 1806 to prevent its falling into French hands. The British government shows no willingness to return this beautiful and fertile land to its former owners. Indeed, the administration has treated the settlers with some hostility, outlawing the use of Dutch as an official language. In consequence many of these people have quit the province, going to other regions where there are more of their countrymen. Those that are left are resentful of their new overlords.

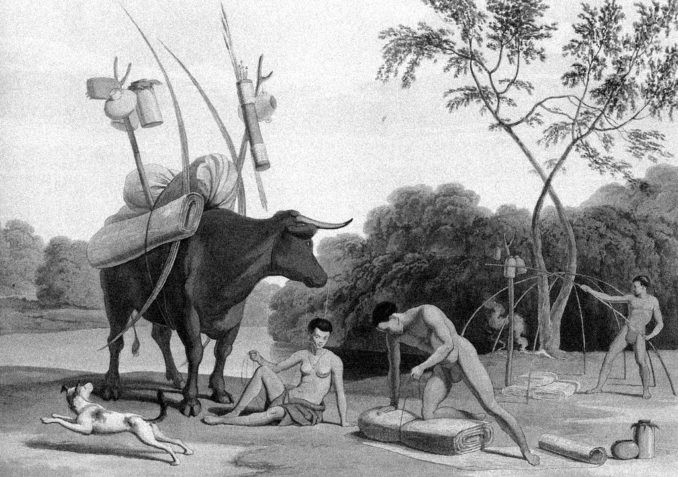

The natives are also in motion. Formerly this land was inhabited by the Khoikhoi, a people somewhat different from the conventional idea of Africans, as they are relatively light-skinned and have a slightly Oriental cast of countenance. They are nomadic cattle herders and live in hemispherical tents similar to those that one of our sailors has seen in Mongolia, to the east of Russia, where the local name for them is yurt.

In recent years these people have retreated before the advance of another people, also cattle herders, whose name I cannot properly set down on paper. The nearest I can render it is Kosa, but the consonant I have represented as K is a peculiar click that defies both description and utterance. They are darker and more typically African in their appearance.

The natives seem resigned to European occupation, though there is a good deal of cattle theft. However, I cannot avoid feeling that a land where four nations are jostling for position cannot remain peaceful for long, and that sooner or later smouldering ill feeling will erupt into violence.

February 5th, 1811.

Our ramblings took us to Simon’s Town, on the east side of the Cape peninsula and named after a former Dutch governor, Simon van der Stel. Here we met Captain Whimbrel again, for the town now houses a British naval base to which he had moved his ship in order to have some minor repairs performed.

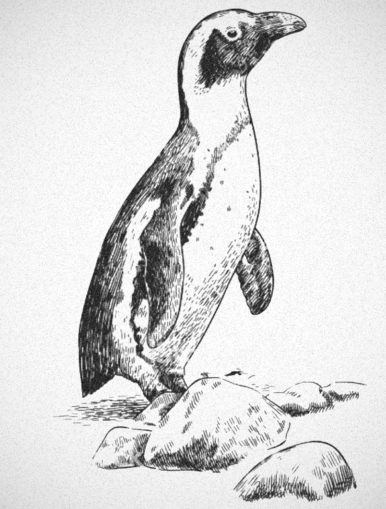

We also met, to our astonishment, a flock of penguins on the beach. None of us had ever seen this flightless bird of the Southern Ocean before, and had no idea that their realm extended so far to the north. However, as the old proverb has it, Ἀεὶ φέρει τι Λιβύη καινόν, Africa always brings something new. This must be the first time that a polar bear has encountered a penguin – or at least a southern penguin, for the name was originally applied to a different bird, the Great Auk of the north Atlantic, which has now been hunted almost to extinction.

Never having seen a bear before, they showed no fear of us, and Boris and Beaivi swam among them. They reported that the creatures, so comically ungainly on land, could travel with astonishing speed under water, propelling themselves with their wings which resemble the flippers of a seal. Boris said that he had tactfully refrained from trying to eat any of them; but if he had wished to, he would have had a devil of a time catching these swift fowls as they fly gracefully through the deep.

February 7th, 1811.

We are at sea again. Our plan is to take a westerly course home, a longer route but probably a faster one as the winds will be more favourable once we have recrossed the line, for they blow roughly in a clockwise circle in the North Atlantic. Also, the African coast is as dangerous to sailors on its west side as it is on the east, and all should heed the old adage,

Take care, beware

The Bight of Benin.

One comes out

Though forty go in.

We plan to make our next landfall in Brazil, probably at Recife on the eastern tip of the South American continent. It would be a pity to conclude so long and wide a voyage without visiting America, a continent to which no one on board has ventured before, though we passed within a few miles of one of its less hospitable regions when we came through the Bering Strait.

Copyright © Tachybaptus 2019

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file