Ey-up miduks, as they say here in my adopted city. This ramble all started with a day off. A Friday, to be precise. It was no particular Friday, and there was no particular reason for taking a day off. I’d just worked a few too many extra hours so it felt like I needed a break. As the delightful lockdown was still dragging on, there wasn’t a great deal we could easily do or many places we could go.

OK, we (Mr Sharpie and I) thought, let’s just make the best of it, eh. The morning had started off bright, and it wasn’t all that cold, so we decided on a walk…well, more of a wandering amble, with a vague plan to find somewhere selling take-away coffee and a bench somewhere pleasant to sit and drink it. It turned into quite an adventure.

We set off towards the city centre (or, in the local lingo, dahn tahn), heading down the usually hectic Derby Road. That’s quite a strange experience these days as, even at about 7 o’clock in the morning, at what should be the height of the rush hour, the streets are spookily quiet. Mind you, it does mean that the streetcleaners have been able to crack on and get the place looking near spotless. Amazing what a dearth of students does for an area.

Even the main thoroughfare through the city for public transport, Lower Parliament Street, was pretty laid back on this Friday morning. Apart from the ubiquitous, but near empty buses, and the odd Deliveroo cyclist (yes, even at this time of day) there were few souls abroad. The Union flag above the Corinthian columns of the Theatre Royal fluttered limply in a half-hearted breeze. The Theatre was the vision of William and John Lambert, lace factory owners and philanthropists who strove to create a luxurious ‘temple of drama‘ and a place of ‘innocent recreation and of moral and intellectual culture’. Doors opened on Monday, 25th September 1865 with a production of Sheridan’s ‘The School for Scandal’.

Nottingham’s Theatre Royal

© The real GoG, licensed under CC BY 2.0

We decided to give Old Market Square with its chain coffee shops a miss, and head for the rather more upmarket Hockley and Lace Market areas, some the oldest areas in the city. Making up part of today’s Creative Quarter, there’s bound to be a nice little independent coffee shop or two there. Hmmm, the buildings and likely looking shopfronts are still there all right, but not one of them is open so scratch that plan. Cheers, Bozzie babe!

Thankfully, my clever husband remembered seeing something about an ‘all day breakfast’ café by the old fruit and veg market and he was fairly sure that it opened early. Off we wandered through Hockley and down the hill, to see for ourselves. The street we walked along, was Goose Gate.

Goose Gate was the home of John Boot’s first shop, which he opened in 1849, with his wife Mary. His son, Jesse, was born a year later. John had been an agricultural worker but, suffering with ill-health, decided to set up a small store in the poorest area of town selling herbal medicines to treat a variety of ailments. The ingredients for his cordials, elixirs and potions were often made from plants that grew locally, in areas like the nearby Meadows. As the lowlier working classes couldn’t afford to pay doctors’ fees, his shop soon became popular.

The original Boots the Chemists shopfront had (and indeed still has), large windows with slender iron ‘Solomonic columns’ to afford customers a glimpse of the chemists in action. A smart business ploy. After John died in 1861, Mary Boot kept the business going until her son, Jesse, left school. The rest, as they say, is history.

The first Boot’s, Goose Gate

© Alan Murray-Rust, licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

As we reached the foot of the hill and crossed the road to the edge of the old market, we spotted an A-board. We were in luck, as there it was, and it was indeed open! Yes, the corner café, belly-busting stalwart of Sneinton Market saved the day with welcome takeaway cups of hot coffee. You might think that a sticky bun was involved, but I couldn’t possibly comment.

The Market, and the area surrounding it, has a fascinating history, and as we sat on a rather chilly metal bench on Sneinton Marketplace (which, oddly, isn’t in Sneinton) sipping our hot drinks, we decided we’d like to know more. We were already aware that this area, bordering St Ann’s, has had a somewhat chequered past, but one which has a direct link to fortunes of the city.

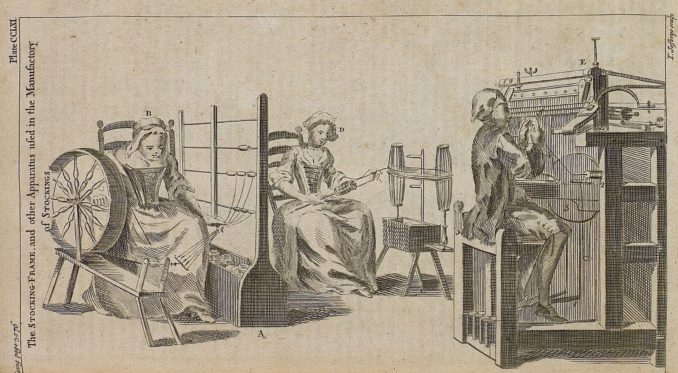

The key to Nottingham’s growing prosperity was textile manufacturing, but it has a capricious history. In 1589, William Lee, curate of Calverton (a few miles outside Nottingham) invented the stocking frame. There’s a whimsical tale about Lee falling in love with a young woman who, whenever he went to visit, was occupied, diligently knitting for her living. To liberate her from her labours, he invented a machine to knit for her.

Although a massive technological step, the poor man didn’t benefit from his brainchild. Eager for patronage, M.P. for Nottingham, Richard Parkyns, Esquire, brought Lee to London where he demonstrated the knitting frame to the first Queen Elizabeth. However, she refused patronage, concerned that this machine would make destitute her subjects whose livelihoods depended on their handicraft.

Though disappointed, Lee continued to improve to his invention, and Parkyns soon introduced him to the French Ambassador who reported back to King Henry IV of France. Henry was so impressed that he invited Lee to France. With his machinery, his wife, his brother and a group of workmen, Lee went to Rouen, where they settled and worked to the great satisfaction of the King. At this point the hosiery trade might have been forever lost to England and Lee become a rich man, but the King was assassinated in Paris in May 1610 by François Ravaillac. Lee’s patron gone, he died in Paris a few years later.

Lee’s workmen and brother returned to England, setting up a framework knitting industry in London. But they gradually felt more and more threatened by overseas competition, so lobbied His Highness the most Serene and most Illustrious Oliver Cromwell, Lord Protector of the Commonwealth of England, Scotland, and Ireland, and the Dominions and Territories, asking to found a body to regulate the trade, and prevent the export of frames. In 1657 Cromwell granted The Worshipful Company of Framework Knitters its charter of incorporation.

The Stocking-Frame and other Apparatus

© Biblioteca Rector Machado y Nuñez, licensed under CC PDM 1.0

Use of the hand-knitting frames slowly spread across England, with many small improvements along the way. Then in 1769, a Nottingham clockmaker, Samuel Wise, took out a patent for an adapted method which changed the upright hand-frame into a rotary stocking frame, allowing mechanical power to be applied, revolutionising the textile industry.

At this point, two of the pioneers of the mechanised textile industry, Richard Arkwright (who introduced the waterwheel powered spinning frame and carding engine) and James Hargreaves (of spinning jenny fame) settled in Nottingham. Whilst it never did become a centre of cotton and worsted spinning, Britain’s hosiery and knitwear industry took off. Production of stockings centred around the East Midlands, with Nottinghamshire (cotton stockings), Derbyshire (silk stockings) and Leicestershire (wool stockings).

The impact of hosiery production on the city of Nottingham was staggering, as the population increased from about 11,000 in 1750 to around 29,000 over the next fifty years, with the migration of workers and their families from the countryside into the city looking for work in the then hosiery dominated, textiles industry.

But it wasn’t all plain sailing as the British economy was in a parlous state by the early 1800s, not least because of high taxes raised to pay for various conflicts. The already-astronomical cost of the Napoleonic Wars was exacerbated by the War of 1812, when tensions with the United States erupted over American citizens being captured on the open seas and ‘pressed’ to man the Royal Navy. It’s said that over 15,000 American men were coerced in this manner between 1793 and 1812.

To make matters worse, this period of high taxation coincided with a decline in the hosiery industry because of a change in fashions, with gentlemen beginning to prefer trousers over stocking hose worn with knee breeches. But the decline of hosiery was offset by the rise of lace manufacture (originally another cottage industry, handmade ‘pillow’ lace was a slow and expensive process), so many workers turned their hands to lacemaking. In the years between 1822 and 1825 work was plentiful, and the population of Nottingham continued to grow.

Machine-made lace had evolved directly out of hosiery, when a farmer’s son, John Heathcoat, was apprenticed to a stocking-maker near Loughborough. With a natural bent for machinery, he studied the hand movements of a manual lace maker and reproduced them in the 1809 ‘Old Loughborough’ Bobbinet machine, which mechanised lace production, creating smooth, un-patterned tulle, a fine man-made netting. Further major technical developments soon followed.

Possibly the most important improvements were those made in 1813 by John Leavers. His house at the top of Derby Road is sadly long gone, but the site is marked by a half-forgotten plaque, almost unseen by the traffic passing by, which reads:

In this house lived John Leavers, Inventor of the Leavers Lace Machine 1913

[The House on this site to which the above plaque was fixed was demolished in July 1959]

Leavers’ plaque

© SharpieType301 2021

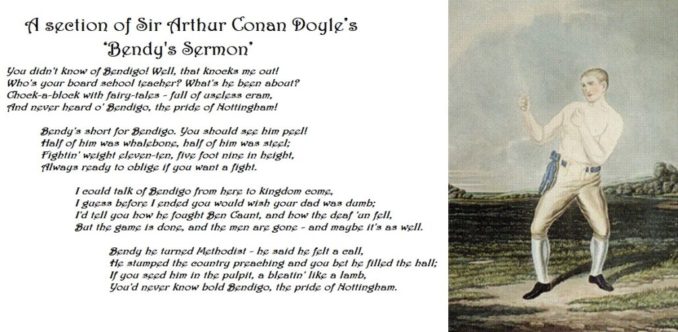

Originally making an extremely fine, high quality tulle, the Leavers lace machine was to lay the foundations of the machine lace trade. Interestingly, the carriages and bobbins needed for the improvements had to be extremely thin and precisely made. These were made for Leavers by Benjamin Thompson, father of the legendary Nottingham prize fighter, Bendigo, more of whom later.

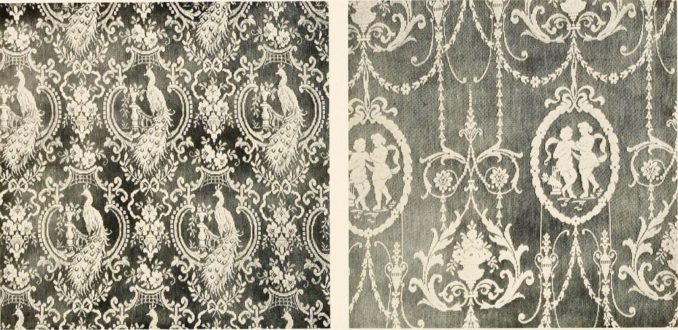

Already a step-up in quality, more was to follow when the Leavers lace machine was adapted to be controlled by Jacquard apparatus. This allowed the creation of beautifully complex patterns, using finest Egyptian cotton to manufacture the closest thing to expensive handmade pillow-lace.

Leavers machine with Jacquard

© ClemRutter, licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International

Jacquard apparatus controlled the lace machine using a series of punched pasteboard cards, laced together with string to form a continuous ‘chain’. Each card would have multiple rows of punched holes, and one complete card corresponded to a single row of the lace design. Many such cards were required to produce the finished, patterned lace.

The next big development was the Nottingham lace curtain machine, invented by John Livesey in 1846. This allowed much wider lace fabric to be produced in increasingly long lengths. These machines went on to make miles of the decorative lace curtaining which screened Victorian and later windows.

Machine-made lace curtain

Image from page 131 of ‘Decorative textiles’, No known copyright restrictions

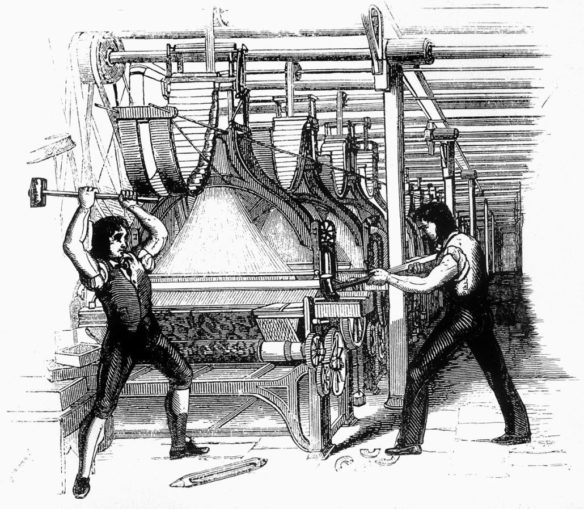

The wonders of industrialisation brought great benefits to the people of Nottingham, but also considerable distress. The Luddite movement also emerged during this harsh economic climate, as new inventions meant textiles could be produced faster and more cheaply by machines operated by unskilled, lower-paid labourers, than by traditional methods.

The Luddites attacked what they perceived as the reason for the decline in their livelihoods and in 1811, the first year of the riots, over a thousand machines, both hosiery and lace, were smashed. Machine-breaking was one of few tactics available to them, despite harsh sentences if found guilty, as the Luddites end-goal was to enhance their bargaining position with the mill owners.

Luddites, machine-breaking

© Original unknown, public domain

But the destruction of machinery led instead to the passing of the Frame Breaking Act 1812, which made ‘machine breaking’ a capital crime. No less than fourteen Luddites were hanged by 1813, and many more were transported to Australia.

The English peer, poet and politician, Lord Byron (he of the tame bear while a student at Trinity College, Cambridge), composed his poem the ‘Song For The Luddites’ and condemned the government’s callous policies and ruthless repression in the House of Lords on 27 February 1812, opposing the death penalty, stating:

“I have been in some of the most oppressed provinces of Turkey; but never, under the most despotic of infidel governments, did I behold such squalid wretchedness as I have seen since my return, in the very heart of a Christian country”.

Lord Byron in Albanian Dress

© irinaraquel, licensed under CC PDM 1.0

But despite the best efforts of the Luddites, and Byron, the machines were here to stay. By the 1840s, lace and textile manufacture had given Nottingham a new nickname, ‘City of Lace’. From 1850 onwards more factories and warehouses were built in an area which became known as the Lace Market, and the city of Nottingham was firmly established as a world-leading centre for lace production.

As with many industrial centres it had attracted a large influx of workers and, by 1832, with a population of 50,000 and rising, no less than 186 lace manufacturers and 70 hosiery manufacturers were listed in the first edition of William White’s ‘History, Gazetteer and Directory of Nottinghamshire’.

Housing was built on every available piece of land until Nottingham became absurdly congested. Many of the wealthier members of the lace industry moved into the villages just beyond the town boundaries. The more affluent working classes moved out to the suburbs, but poorer workers were trapped, living in more than 7,000 back-to-backs that ran from Narrow Marsh to Sneinton, and in The Rookeries (mediaeval lanes between Long Row and Parliament Street).

It was extremely overcrowded and disease-ridden, with people living cheek-by-jowl in dreadful conditions. The majority of these back-to-backs, some of the worst slums in Europe, had no kitchen. Ventilation was poor to non-existent, and up to forty households shared one privy and a standpipe. More problematic, a good proportion of the older part of the city’s dwelling-houses or sets of dwelling rooms actually had their communal privies situated directly underneath, collecting the night soil in the caves. Part of the Kingdom of Mercia, Nottingham was originally called Tiggua Cobaucc or Tig Guocobauc (the ‘Place or House of Cave Dwellings’), a fact first mentioned in The Life Of King Alfred, written by Welsh monk and historian, Asser, the Bishop of Sherborne, in 893 AD.

So unpleasant were conditions in Nottingham, that it’s said, rather tongue-in-cheek, that even the plague stayed away! As early as 1802, widespread infectious diseases such as typhoid, typhus, tuberculosis and cholera were rife, and a fever ward had been built at Nottingham General Hospital. Despite that provision, in 1832, some 330 people died during an outbreak of cholera. Something, it was recognised, had to be done.

By 1845, the commissioner J.R. Martin, in his ‘Report on the Sanatory Condition of Nottingham, Coventry, Leicester, Derby, Norwich, and Portsmouth‘, presented to Parliament, remarked:

In all the parishes there are numbers of streets to be found of the worst construction as regards ventilation, construction of habitation, sewerage, supply of water, paving, and lighting; but, as might be expected, these defects are most conspicuous in the older quarters, and in the lower levels, as under the Castle, and down to the Narrow-Marsh, Canal Street, Leen-side, and in the greater part of St. Ann’s and Byron Wards…

I believe that nowhere else shall we find so large a mass of inhabitants crowded into courts, alleys, and lanes, as in Nottingham, and those, too, of the worst possible construction. Here they are clustered upon each other; court within court, yard within yard, and lane within lane, in a manner to defy description, – all extending right and left from the long narrow streets above referred to. The courts are always, without exception, approached through a low-arched tunnel of some 30 or 36 inches wide, about 8 feet high, and from 20 to 30 feet long, so as to place ventilation or direct solar exposure out of possibility on the space described. The courts are noisome, narrow, unprovided with adequate means for the removal of refuse, ill-ventilated, and wretched in the extreme, with a gutter, or surface-drain, running down the centre: they have no back yards, and the privies are common to the whole court: altogether they present scenes of a deplorable character, and of surprising filth and discomfort. It is just the same with lanes and alleys, with the exception that these last are not closed at each end, like the courts. In all these confined quarters, too, the refuse matter is allowed to accumulate until, by its mass and its advanced putrefacation, it shall have acquired value as manure; and thus it is sold and carted away by the “muck majors”, as the collectors of manure are called in Nottingham.

In the area where The Avenues of Sneinton Market now stand, the overcrowded back-to-back housing was collectively known as ‘The Bottoms’, not least because of their lowly situation. This housing was demolished following the Nottingham Inclosure Act 1845 (which eventually ‘released’ more land for building and banned the renting of cellars and caves as homes to the poor), and the whole area was rebuilt to provide better housing and public amenities. The new 1850s residences in Finch Street, Sheridan Street, Brougham Street, Lucknow Street, Wood Street and Pipe Street had adequate light and access to some outdoor space.

Alongside the building programme, an offshoot market developed in the square near to the new housing. For hundreds of years, Nottingham’s Market Square, in the centre of the city, had been the home of the main wholesale markets, but the increasing population in a restricted space made expansion problematic and the call for a ‘local’ market inevitable. The square near the 1850s housing was also used for public meetings, travelling fairs and religious gatherings. This overspill market was hugely popular, so flourished and expanded, albeit with makeshift, rickety wooden stalls.

So popular that, in the 1930s, Nottingham Corporation decided to modernise the market, and, in 1934, Nottingham launched its second slum clearance scheme. This meant goodbye to the streets rebuilt in the 1850s. Although an improvement over the old back-to-backs, that housing was still regarded as poor (and was still known as ‘The Bottoms’). In the place of the streets, a new dedicated market was built, with rows of shuttered and glazed open-fronted units with sturdy roofs, The Avenues.

On a corner opposite the entranceways to the 1930s market avenues, the aptly named café known as ‘The Avenues, formally (sic) known as Tasty Bites’, is where we bought our coffee. The café is handily marked out by a rather snazzy cartouche of glazed bricks in the shape of a hand of yellow bananas. This architectural oddity comes from another Nottingham success story.

The Avenues Café

© John Sutton, licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

Back in the day, the market stall belonging to W.H. Hinton and Sons, fruit merchants, was the only one to stock bananas in Nottingham. This precious fruit was transported to the city by train. On arrival, the bananas were green, but they were ripened for sale by storing them underground in the caves on Manvers Street. There, they were lovingly cosseted until perfectly yellow and ripe. In the late 1950s, Hinton’s sold out to Fyffes, and the building from which the café now operates once housed the Fyffes banana warehouse. Fyffes were the biggest importers and distributors of bananas in Europe, and the hand of bananas harks back to that.

The market continued to thrive, right up until the advent of supermarkets and superstores which took business away from the stallholders. It fell into disrepair by the late 1970s, with some of the Avenues partly destroyed by fire. Although still in use, to some extent, it remained a sad and dismal space for decades.

The Avenues – Sneinton Market, c. 2008

© Alan Murray-Rust, licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

Sneinton Market today has been gentrified and forms an integral part of Nottingham’s Creative Quarter. It’s now bright and colourful and, pre-Covid, was prospering once again. A hub attracting artists, musicians, entertainers, designer/makers and more, its Plaza is described as “a cool venue for just chilling with friends or enjoying live music events, street food, market stalls and performing artists”.

The Avenues host a couple of dozen creative businesses, and it’s also the headquarters of The Left Lion culture magazine, a real Nottingham ‘name’. The market’s old Avenues are the place to buy unusual and quirky gifts or treats, or find artisan bread, cakes and coffee, football fan-art, the Neon Raptor Brewing Co., plus a fabulous household plant shop and a luxury vegan chocolatier.

Artisan coffee, there’s posh!

© SharpieType301 2017

Once we’d finished our coffee, we wandered onwards up into St Ann’s, an area we’d never properly explored on foot. A chapel was built there in 1409, and the waters of the spring and well were thought to have magical healing powers. In 1500, this area took its name from St Ann’s Well, but several ancient names had been used beforehand, including Peas Hill (1230), Hunger Hills (1304) and Clay Fields.

Construction, proper, in this area began in early 1839, with a magnificent tree-lined recreation walk, Corporation Oaks, between St Ann’s Well Road and Toad Hill. This was developed with sizeable houses for professionals, such as solicitors, and doctors, and the factory owners. But the 1845 Inclosure Act allowed some land to be used for basic housing and St Ann’s ‘New Town’ was built expressly for the working poor.

By the 1890s, it was bustling, with rows of back-to-back terraced houses (some 10,000 in all) on a gridiron plan arranged around courts of ten houses, with cobbled streets, factories, shops, a large number of pubs, one on almost every street corner, and beer off-licences.

St Ann’s estate has always seemed culturally separate from Nottingham. A place of hard work and low pay in its heyday, infant mortality was three times the national average. Almost viewed as a town within a town, it was an area that the local constabulary refused to enter, for good reason. Any ‘policing’ was overseen by the residents relying on ‘family affiliation’.

Not all that different in more recent years, you might think. Certainly, around the Millennium, the gun-crazy, drug-fuelled gang culture of Nottingham meant that almost half of the killings were deliberate executions, earning the city the sobriquets ‘Shottingham’ and the ‘Assassination City’. In 2006, there were an estimated six to seven shootings a month in the ‘gun capital’. While things have definitely improved, even in 2020 the St Ann’s area ranked in the top 10% of deprived areas nationally.

Only a few of the 1860s terraces remain. Today these streets, including The Promenade, overlooking Victoria Park, are a distinctive and popular part of the St Ann’s and Sneinton district. Of painted brick, with slate roofs, The Promenade is a terrace of 30, three-storey houses stepped uphill from east to west. It was built as part of a planned development including Campbell Grove and Robin Hood Terrace, which followed the Inclosure Act of 1845.

The Promenade, St Ann’s

© SharpieType301 2021

Though few houses had gardens and there was only the small Victoria Park, there was open space. St Ann’s Allotments, one of the oldest and largest inner city allotment sites in the world, which lies between St Ann’s Well Road and Woodborough Road. Established in the 1830s, when the ‘New Town’ was envisaged, the Allotments cover three interconnected sites: Hungerhill Gardens, Stonepit Coppice and Gorsey Close.

The Allotments are laid out as ‘gardens’ with boundary hedges or boarded fences, as once commonly found just outside the centres of many industrial towns, few of which have survived. Some plots still contain summerhouses and glasshouses, typically Victorian structures. The 670 allotment gardens are now Grade 2* listed, being of ‘Special Historic Interest’, and Site of Importance for Nature Conservation.

These days, there is another green space, St Mary’s Rest Garden, which is now an extension to the small Victoria Park, where city workers can enjoy a lunchtime wander or a peaceful(ish) evening walk around the Tree Trail. Both parts have been planted with a variety of native and non-native trees.

Victoria Park is the former Meadow Platt which, in the 1800s became Bath Street Cricket Ground. Unfortunately, the restricted space meant the pitches were close together, making it hazardous to both the players and audience, so by the 1890s it was converted into a pleasure park.

The park lies close to the Victoria (Swimming) Baths. The Victoria Baths were one of the public amenities, planned as part of the Inclosure Act, the oldest and first baths and washhouses in Nottingham. Opened to the public in December 1850. Wylie’s Nottingham handbook of 1852 states:

“The building is of brick and one storey high; the interior is commodious and well fitted up. There are baths both for males and females, and the charges are exceedingly moderate. They are open on Sundays as well as on week-days, and the wash-houses are open on the week-days from eight o’clock a.m. to eight o’clock p.m. In the latter department there is suitable drying apparatus, and this has been of much benefit among the humbler classes of the community, whose homes do not furnish the requisite convenience for washing. Altogether the admirable situation is calculated to elevate both the physical and moral nature of the inhabitants.”

St Mary’s Rest Garden has a rather macabre history, as it was formerly the St Ann’s Cemetery, and many of the original headstones can be seen still, propped up along the walls. The land was donated by Samuel Fox, a Quaker, to provide space for burials following the deadly cholera epidemic in 1832 and is where many of the fatalities were laid to rest.

An account by Henry Field, in ‘The date-book of remarkable and memorable events connected with Nottingham and its neighbourhood, from authentic records. Part 2, 1750-1884’ describes the speed at which the epidemic spread and how rapidly its effects were felt:

“Mr John Kale, basket-maker, of South Street, aged 23 years, and his wife, aged 21 years, died on the 12th of October.

They were both in perfect health when they arose in the morning, but soon after the wife complained of being unwell; not suspecting anything materially amiss, he went on his business to Hucknall, and on returning through Bulwell in the afternoon, was taken ill, and was so bad that he died on the road, and so rapid was the decomposition of the body, that it was obliged to be buried the same evening at Basford.

In the meantime, the wife sickened, and died the same night, of cholera, at South Street in Nottingham, leaving an orphan, about a year old.”

In addition to the many cholera victims, the former burial ground of St Mary’s Rest Garden, holds another Nottingham secret. It is the resting place of the city’s sporting legend, William Abednego ‘Bendigo’ Thompson.

William Thompson was born on 11 October 1811, to Benjamin and Mary Thompson, in New Yard, one of the city’s many slums. He was the youngest of 21 children and the third of triplets named after the Old Testament characters, Shadrach, Meshach and Abednego, forced to enter King Nebuchadnezzar’s fiery furnace after declining to abandon their religion and worship Babylonian gods. His early life, like many of that period, was not easy.

The former New Yard, Bendigo’s birthplace

© SharpieType301 2021

He was just 15 when, following the death of his father, he and his mother were sent to the Nottingham Workhouse. Though he wasn’t there long, his experience of that crippling period of poverty meant that he pledged never to return. He found work as an iron turner, which greatly improved his strength and helped him develop his muscular physique. A promising young sportsman he had an ability to box, so began taking part in illegal prize, or bare-knuckle fights to earn a little money to support the family, encouraged by his mother.

By the age of 18, fighting under his middle name, Abednego, he had defeated his first eight opponents, and by 21 years of age was a regular and successful prize fighter, even though with these fights being illegal and a breach of the peace, he was arrested after most of them.

William wasn’t a big man, standing just under five feet ten inches and weighing around 12 stone. Smaller and lighter than many of the top fighters of the time, he was nevertheless extremely strong, and incredibly agile and fast. He turned that into an advantage and first earned the name ‘Bendy’ due to his fighting method, bobbing and weaving around the ring. This name later shifted, and ‘Bendy’ Abednego became ‘Bendigo’.

William Abednego ‘Bendigo’ Thompson

© Antique Aquatint by Charles Hunt, public domain

Prize fights were wild, could last up to 100 rounds, and were fought with precious few rules. One of Bendigo’s most famous fights was with his great rival, Ben Caunt, which went for 96 rounds and lasted over two hours before Caunt collapsed from exhaustion. The only directions to govern them had been drawn up in 1743 by a Thames waterman called John ‘Jack’ Broughton, who set seven rules of conduct for his own amphitheatre (an interesting development, given that Broughton’s ring offered other brutal events, such as bearbaiting and fights with weapons). Grappling, the cross-buttocks throw, suplexes and clinching was legal and ‘fibbing’, holding your opponent by the neck or hair to pummel him, allowed too. Kicking was not uncommon, and Bendigo was expert in this.

A tricky fighter, Bendigo punched hard and fast. Credited with inventing the Southpaw stance, he was said to be devoid of fear. The Muhammad Ali of his time, he was also a real crowd-pleaser. Thousands of people, of all classes, gathered to watch him fight, dancing around his opponents and even doing somersaults in the ring during a fight to taunt them. Sometimes branded ‘The Nottingham Jester’ he baited his opponents with a steady stream of humorous taunts and insults, distracting them with rhymes and verse and then felling them with his powerful left hand. But he trained hard for all his fights and was a highly skilled pugilist. In February 1839, at 28, Bendigo was crowned as the Champion Prize Fighter of All England, defeating the feared Londoner, James ‘Deaf’ Burke.

His last title bout took place in 1850, against the Redditch fighter, Tom Paddock, when Bendigo was 39. The fight (which lasted a mere 49 rounds!) went his way when Paddock, eleven years his junior, but who had a vicious temper, hit Thompson while he was down in the last round. Getting on in years, Thompson had not wanted this fight—his mother had badgered him into it. Neighbours had heard her screeching at him:

‘’Ya feverish swine. ’Oo’s gonna put bread on the table? Get ya sorry backside into that ring, ya yellow bellowed wuss’’ and “I tell ya this Bendy, if ya don’t tek up the fight you’re a coward. And I tell ya more. If ya don’t fight ‘im, I’ll take up the challenge mi-sen.”

Once retired, after this last fight, he spent time fishing on his beloved Trent, winning some All-England Fishing awards. For a while, he was appointed boxing coach at Oxford University, but he soon returned to Nottingham. Not long afterwards, his mother died. In his grief, he turned to drink, being sent to the House of Correction nearly thirty times as drunk and disorderly.

Then, attending a revivalist meeting held by ex-coal miner Richard Weaver, he finally broke that self-destructive cycle and gave himself to God. He was invited onto the platform and delivered a powerful sermon. At the age of 60, although illiterate and unable to read the Bible, he became a preacher, regaining the respect he’d previously enjoyed. He spent the next few years touring the country, drawing massive crowds. Preaching, he would take up a boxer’s stance, point to his trophies and tell the congregation:

“See them belts; see them cups; I used to fight for those, but now I fight for Christ!”

In August 1880, at 69 years of age he died after a fall at his home, breaking ribs which punctured his lung. The Times of London published his obituary, an unusual honour for a man of his lowly birth, and it’s said that his funeral procession was over a mile long. His tomb, in St Mary’s Rest Garden is topped by a carved stone lion, bearing just a simple inscription:

“In life always brave,

Fighting like a Lion;

In Death like a Lamb,

Tranquil in Zion”

Bendigo’s grave

© SharpieType301 2021

Well after the legendary William Abednego ‘Bendigo’ Thompson was no more, his fame lived on. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, though born some forty years after Bendigo died, wrote a verse to him, a small portion of which is shown below. All in all, this ended up being quite a walk in the past.

© SharpieType301 2021

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file

Audio Player