In May 1969 my uncle, John Alldridge, described the voyage of Allcock and Brown for the Montreal Star. This is the fourth of his reports. – Jerry F

John Alldridge recalls the epic flight of Alcock and Brown,

Montreal Star – Newspapers.com, reproduced with permission

Like most cities, St. John’s, Newfoundland, has spread its boundaries considerably in 50 years. Lester Field, on the western edge of the city, is a field no more, but is covered by rows of neat suburban homes.

To John Alcock, seeing that field for the first time on that dreary wet May morning in 1919, it must have seemed as hopeless as all the other sites they had visited. A stone dyke ran across it, while trees and boulders were dotted about haphazard.

But it was about the right length for take-off. And there was no alternative, anyway. There is little flat ground anywhere near St. John’s.

Alcock and Brown had arrived at St. John’s from Halifax on May 13, after a long and wearying railway journey, to find their rivals Raynham and Hawker all ready for take off and only waiting for a few hours of decent weather. So were the American flying boats out at Trepassey.

Three days later, on the 16th, the three Americans roared off out of Trepassey harbour, flying in formation on course for the Azores … On May 27 Lieut Commander Read was to bring one of the three safely down on the Tagus River at Lisbon – the first plane across, but not non-stop. It made the trip in two long and perilous hops: 2,400 miles in 11 days.

Meantime their own aircraft was still somewhere in the Atlantic with his mechanics. And then there would have to be the complicated business of assembling it in an open field. Moreover the only two available airstrips had already been rented by Hawker and Raynham. To Alcock and Brown it must have been a frustrating moment.

But in the next week their fortunes radically changed. On May 17 Hawker and Mackenzie-Grieve got away at last in their Sopwith Atlantic. A few hours later Raynham and Morgan look off after them in their red-and-yellow Rolls-Martinsyde.

Both flights ended in gallant failure. Rayham’s attempt was soon over. Just as his wheels left the ground a violent gust of wind caught the plane and tipped it over. It crashed badly. Raynham got out without a scratch but Morgan, his navigator, had serious head injuries.

About 500 miles out over the Atlantic Hawker, battling through heavy cloud and rain, ran into trouble.

His engine stopped, and he was only 20 ft above the sea when he restarted it. Realising his position now was desperate he decided to fly low across the shipping lanes looking for a vessel.

When the plane was at its last gasp they sighted a small Danish steamer and dropped into a choppy sea beside it. After great difficulty the fliers were picked up. On Sunday, May 25, exactly a week after they had taken off from St. John’s, Hawker and Mackenzie-Grieve were landed safely in Scotland.

So now it was to be a straight race between the Vimy and the Handley Page, 60 miles away at Harbour Grace. That is, providing the Vimy could arrive in time.

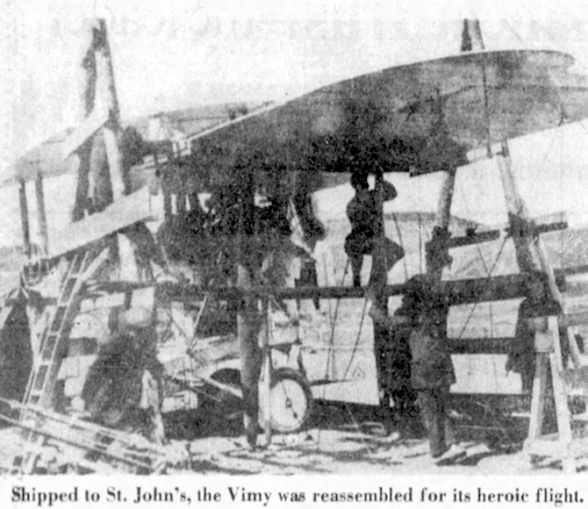

On May 26 the Vimy arrived at St. John’s on the freighter Glenavon. Realising that it would be some weeks before he could make another attempt, Freddie Raynham very sportingly offered Alcock the use of his field at Quidi Vidi as an assembly point. So the Vimy, packed in its huge crates, was towed out to Quidi Vidi by teams of horses.

For a week Alcock, Brown and their devoted mechanics worked on it in bitter cold and ceaseless rain; spurred on by the knowledge that only 60 miles away the Handley Page was being prepared for its first test flight. Brown himself installed the wireless and navigational gear while Alcock supervised the general assembly.

Montreal Star – Newspapers.com, reproduced with permission

Montreal Star – Newspapers.com, reproduced with permission

Meanwhile another working party, augmented by sightseers and newspaper reporters waiting for their stories, were clearing Lester’s Field. The boulders were dynamited, trees uprooted and torn down. Within a week a passable runway 500 yards long was ready.

And then almost miraculously the weather began to improve.

Montreal Star – Newspapers.com, reproduced with permission

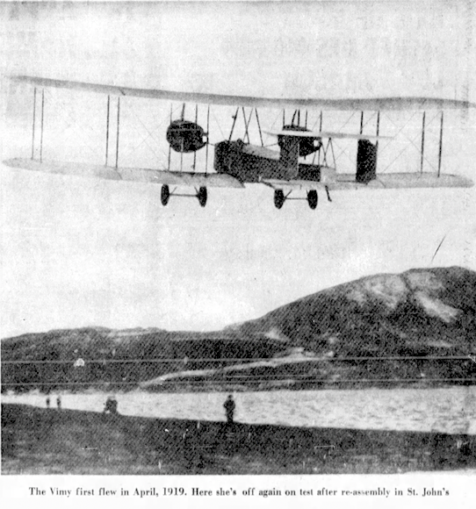

On Monday, June 9, Alcock took the Vimy up for its first test flight in Newfoundland. She behaved perfectly, took off like a bird, and circled St. John’s several times before landing on her new airstrip at Lester’s Field.

Again they were only just in time. The next day the weather closed in again. For almost a week after that they fretted and fumed waiting for another break. Their only consolation was that their rivals at Harbour Grace were enduring the same foul weather.

Then at last, early on the morning of June 14, Lieutenant Clements, the meteorologist borrowed from the RAF, was able to bring in a favourable report.

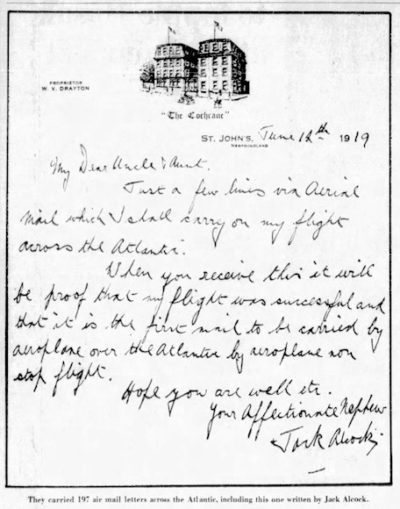

When the news reached Alcock he was still in bed at the Cochrane Hotel, which all the fliers had made their HQ. In great excitement he woke Brown; then grabbed his flying kit and was halfway down the hall before Brown called out that he was still wearing his pyjamas. He returned, chuckling like a child, and put on his best blue suit. Brown dressed as usual in his neat, well-fitting RAF uniform.

It was shortly after 3.30 a.m when they reached Lester’s Field and the sun was just rising. The mechanics had finished their work on the Vimy. The great bomber stood ready, fully loaded, complete to the last split-pin.

A last-minute repair to a petrol feed pump was made as they settled down to wait for the gusty wind to drop. Sitting under the wings of the Vimy they ate their last meal before take-off; a picnic breakfast of cold meat, cheese, and biscuits, and coffee.

At one o’clock Alcock squinted up at the sun and decided the moment for which they had waited so long had finally arrived. Wearing their bulky flying suits (electrically heated by a battery) they walked across to the Vimy and squeezed into that narrow cockpit; Brown sitting on the port side, Alcock on the starboard.

Their food supplies for the journey were handed in — coffee, chocolate, bottled beer, biscuits, and a last-minute bottle of whisky, the gift of the local doctor.

To the newspaper men, watching them settle down, they must have looked pitifully insecure. They had no blind-flying instruments. Their only life-saving gear, if they were forced down in the sea, was a detachable fuel tank on which they might hope to float.

A St. John’s reporter who was an eyewitness wrote: “There was a tense expectancy of danger; the very thought of flying any distance was fantastic to people who, a few weeks earlier, had seen their first aeroplane.

Many of the older folk believed there was something devilish about the strange contraption which Alcock and Brown were trying to fly across the Atlantic.

Maybe, with that thought in mind, they had taken with them two extra passengers — two lucky black cat mascots, “Lucky Jim” was lashed firmly in the strut behind Alcock’s seat, “Twinkletoes” — the gift of Kathleen Kennedy, Brown’s fiancee — stuffed in the breast of Brown’s flying suit. (Though they did not know it, they carried a third mascot — a horseshoe screwed firmly under Alcock’s seat by his mechanic, Harry Couch).

Montreal Star – Newspapers.com, reproduced with permission

Then postmaster Robinson handed over the little white canvas bag that contained 197 airmail letters. Brown carefully stowed them away in the locker behind him. Then up drove their good friend Sir Michael Cashin, Prime Minister of Newfoundland, to shake hands and wish them luck.

“Goodbye, Sir Michael,” said Alcock, “you’ll hear from me in Ireland …”

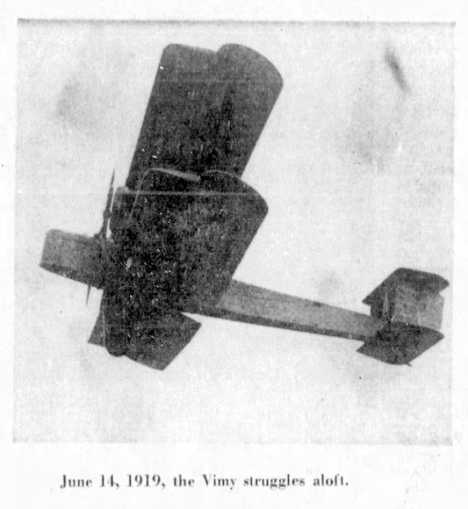

At 1.24 local time, with a shattering roar, the port side engine fired; to be followed a few seconds later by the starboard engine. The onlookers saw a hand rise in a sign of release. A mechanic whipped away the wheel chocks. Then the engines roared out again. The men holding the Vimy dropped on their faces and the wings passed over their heads.

Slowly, desperately slowly, the Vimy lurched into the westerly wind. Ahead still lay a bare 100 yards of rough ground and beyond that a high stone dyke and a fir wood.

The onlookers held their breath as the Vimy, with its three and a half tons of petrol, moved slowly forward. Then still very slowly it began to climb; clearing the dyke and the woods by inches.

Montreal Star – Newspapers.com, reproduced with permission

It was 1:45 p.m. (4:15 GMT). Alcock and Brown were airborne and on their way.

NEXT: Helpless in a storm

Reproduced with permission

© 2022 Newspapers.com

Jerry F 2023