Seventh in a series by my uncle John Alldridge. This article first appeared in the Derby Evening Telegraph in January 1968 – Jerry F

We left Deadwood in the late afternoon and headed West again, confident we could reach Gillette, 90 miles away in Wyoming, in time to make camp before dark.

A century ago late afternoon would have been the very worst time of the day to travel.

For this was Indian country. Even today the broad Interstate Highway sears through a vast undulating sea of grass where towns are few and far apart.

Look where you will, you are encircled by sandstone bluffs, rarely rising a 100 feet above the prairie, yet completely screening you, cutting you off from the world outside.

Behind those bluffs, looming red and sinister in the evening sun, a great war party of Sioux could lie concealed.

For 30 years and more this was a great natural arena in which hordes of fleet, lightly-armed Indians and a handful of slow-moving, ill-equipped American soldiers fought a series of bloody gladiatorial conflicts.

The battles were seldom decisive and the odds were always in favour of the Indians.

Yet behind the Army stood the settlers and the railway builders, the buffalo hunters and the gold-rushers, and the whole march of human progress.

So in defence of his homeland — fanatically brave and often brilliantly led by born guerrilla generals like Red Cloud, Crazy Horse and Chief Joseph — the Indian fought with a desperate fury.

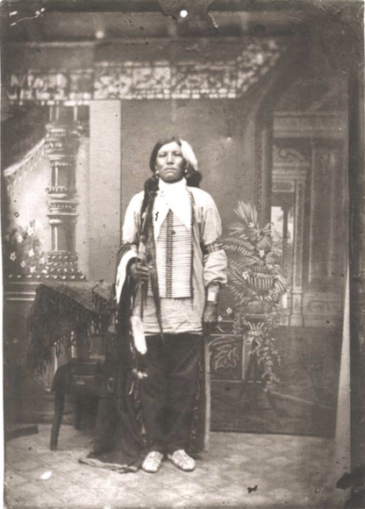

Red Cloud,

Charles Milton Bell – Public domain

Crazy Horse in 1877,

Unknown photographer – Public domain

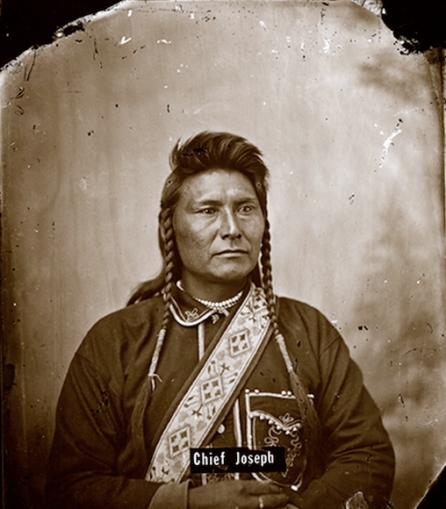

Chief Joseph,

Unknown photographer – Public domain

Opposed to him was a strange assortment of Civil War veterans and green recruits, a makeshift army already soured by demotion, equipped with obsolete weapons, unsuitably clothed, too often forced to fend for itself.

Yet this Army of the West was to prove itself one of the most skilful in American history.

A long-service army isolated in hostile territory, it developed in time that same personality that stamped the Roman legions, the British armies in India and Africa, and the French Foreign Legion.

“High valour it possessed, gallantry sometimes degenerating into foolhardy rashness,” Fairfax Downey tells us in his splendidly exciting history of that Indian-fighting Army.

“It was alternately proud of itself and bored and disgusted with its lot . . . Honour and tradition, loyalty and duty were its gods. And the symbols of the Army’s faith — usually only inwardly acknowledged— were these: the flag waving over the frontier posts and the guidons snapping in the rush of a charge.

“The uniform of blue it so carelessly wore. The anthem the band played at “Retreat” and the bugle call floating in the still air of the plains or ringing brazenly in canyons to stir its fighting heart.”

If Hollywood has dulled that image through endless repetition, out here, in this harsh unchanging scenery, where the very towns are named after the Indian fighters and the battles they fought, its pattern is bright and undimmed.

Its plan of campaign was as old as the Romans. It was based on an extended line of Army posts, or forts, from which it could attack and on which, if pressed, it could fall back.

The Army post, with its flag flying from its jack-staff 100ft. high, could be out on the plains, baking in the sun, or perched on a bare, brown hillside.

Sometimes it was on a river bank and the men could swim.

If it was in hostile territory the post was stockaded and tight. In peaceful country it sprawled ugly and drab.

Big or small, its shape was always the same — dusty parade ground flanked by low buildings of brick or plank or unbarked logs. Officers’ Row on one side, barracks opposite. Quartermaster stores, hospital, offices closing the square.

Here men — and women, too — lived for weeks on end. When they were not fighting Indians, they fought heat, blizzards, the bottle, each other, and just plain boredom.

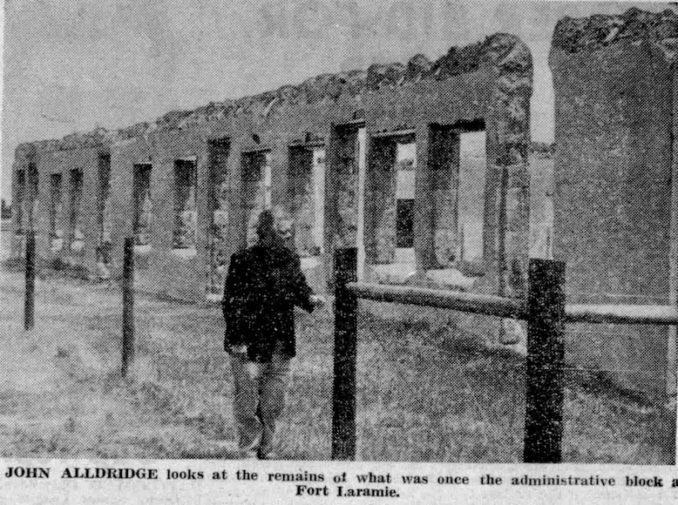

Few of those forts remain. Their life was short. When the need for them was over they were pulled down or abandoned.

One or two, like Fort Laramie, have been carefully and imaginatively restored. For the rest, a grassy mound rising in the middle of an eye-aching plain is all that is left.

Fort Laramie,

Alfred Jacob Miller – Public domain

John Alldridge look at the remains,

Unknown photographer – Reach plc, courtesy of The British Library Board

Of all those historic strong-points there was none more famous than Fort Phil Kearny.

Here was a fort actually built under fire, which endured fire all its short but hectic life and finally was consumed by fire.

We searched a whole morning for it and finally discovered it a few miles south of the town of Sheridan, on an exposed plateau above Big Piney Creek, a tributary of the Powder River.

Around it, to the north, the south, and the west, sweeps a great arc of wooded hills.

In recent years somebody has built the miserable pretence of a stockade around two sides of it. There is a skeleton flagpole and the remains of a hut.

Fort Phil Kearney,

Gcoudert – Licence CC BY-SA 2.5

I climbed up to the summit of a long, greasy rampart where rifle slits once covered enemy attack from the south.

It is perfectly sited; all-round defence with a field of fire uninterrupted for almost a mile.

Old Jim Bridger, the mountain man the Army hired as a scout for five dollars a day, certainly knew his business.

Water is abundant here, and grass and timber. Twin knolls for pickets command its approaches and the Bozeman Trail, winding from the east.

Colonel Henry B. Carrington’s orders were simple. To the fury of the Sioux and Cheyenne, whose hunting grounds these were, he was to build a chain of forts to protect the emigrant and freight trains moving up the trail.

Henry B Carrington,

Unknown photographer – Public domain

Carrington, a fine soldier and experienced Indian fighter, knew this would certainly provoke the biggest and bloodiest Indian rising so far.

But he had his orders. With his 700 men of the 18th U.S. Infantry — many of them recruits armed with old Springfield single-shot muzzle-loaders — a few howitzers, and 226 wagons carrying all the equipment needed for building and maintaining Army forts, he proceeded to carry out those orders to the letter on that early summer morning in 1866.

First they drove a wagon train around and around the rectangle which would enclose the parade ground. Then the woodmen got busy with their axes and the stockade began to rise.

Meanwhile inside the stockade Colonel Carrington was planning one of the finest frontier strongholds ever built. Fort Phil Kearny, he named it. Historians were to call it more appropriately Fort Perilous and Fort Disastrous.

For almost at once the Indians attacked. Red horsemen swooped down on the pickets, bowmen crept up at night and sniped the sentries.

Working parties were cut up, the survivors carried off to suffer slow torture.

But all the time the fort was building. Until, on October 31, 1866, the Stars and Stripes proudly flew from the 120-foot jackstaff for the first time, while the band played patriotic tunes and the colonel made a prideful speech.

Out in the darkness of the Wyoming hills the vengeful Sioux, Arapahoes, and Cheyennes watched and waited for their opportunity.

It came on December 21. From the pickets on a knoll to the south flashed a signal: “Many Indians attacking wood-train.”

“Boots and Saddles,” sang the cavalry trumpets. And out from the fort galloped dashing Captain W. J. Fetterman at the head of a small force of three officers and 77 mounted infantry.

Civil War veteran Capt. William J. Fetterman ,

J. B. Lippincott – Public domain

Fetterman’s orders were clear. He was to relieve the wood train. Under no circumstances was he to pursue the Indians beyond Lodge Trail Ridge.

But Fetterman, a typical glory-hunter, who had boasted he could take 80 men through the whole Sioux nation, had other ideas.

He wanted a real Indian fight. Five miles from the fort and out of sight of it, on a ridge forever after to be called Massacre Ridge, Fetterman and his 79 were caught in a perfect Indian ambush. There were no survivors…

The Indians gave Carrington time to bring in and bury his dead. Then the real attack went in.

On a night of blizzard, when the temperature fell to 30 below and sentries had to be relieved every half-hour the siege began.

It lasted, on and off, until the following August.

During the first days of that siege occurred an epic feat of courage and endurance. Surrounded and hopelessly outnumbered, Carrington asked for a volunteer to ride through to Fort Laramie for help.

The man who stepped forward was a civilian scout, a veteran frontiersman, John Phillips, known as “Portugee.”

Carrington offered him the best horse on the post, his own charger, a Kentucky thoroughbred.

The colonel knew that what Phillips was offering to do was next to impossible — to ride more than 200 miles through encircling Indians in the teeth of a howling blizzard. Yet Phillips did it.

While the officers and ladies of Fort Laramie were dancing at a Christmas Eve ball a bulky figure in a frozen buffalo coat staggered into the ballroom.

He was just able to whisper through blue lips: “Courier from Fort Kearney with important dispatches.”

Then Portugee Phillips collapsed unconscious to the floor. Outside his gallant horse lay dead in the snow. In three days and nights they had travelled 236 miles…

Outside the main gate of Fort Laramie is a cairn of stones and a brass plate that tells the whole story of that great ride. Only one important detail is missing. Nobody remembers the name of the horse…

Help reached Fort Phil Kearney just in time. But Red Cloud and his Sioux kept up their attacks.

Not until early in August, 1867 was the siege finally raised.

In that last all-out Indian attack on a party of woodcutters, caught with their tiny Army escort seven miles from the fort, 32 held off 1,500.

Even so, the Indians got Fort Phil Kearney in the end. The next year the Government signed yet another abortive peace treaty with the Sioux.

They ordered the Army to close the Bozeman Trail and abandon their forts.

For the last time bugles and trumpets rang round the stout walls of the stockade. Bitterly, the blue columns marched out through the gates.

And as they left, down from the hills galloped the yelling Sioux, to take over, unopposed, the fort they could never take by force.

Looking back over their shoulders the soldiers saw the strong point they had fought so long and so hard to hold going up in black smoke.

NEXT: Buffalo Bill — the man and the legend.

© Reach plc, courtesy of The British Library Board

Jerry F 2023