Another article from the Manchester Evening News by my uncle, John Alldridge, this time from April, 1955

Flying straight through from Nairobi to Zanzibar is like falling out of the first act of an early Somerset Maugham story slap into the middle of Chu Chin Chow.

Here at least – I thought – I shall be Away-from-it-All. For 48 blissful hours no more talk of the Mau Mau or Colour Bars or Multi-Racial Governments.

Here, on this scented isle – which still belongs in time to the Arabian Nights, where Sinbad is still the Local Boy Who Made Good, where flying carpets have more significance than flying saucers – I will rest awhile.

With nothing to distract me but the cry of the muezzin and the distant chaffering from the bazaars.

Which only shows how wrong you can be. . . .

I had hoped to browse through the archives of Smith, Mackenzie and Co, the shipping agents where Stanley hired his native porters (at five dollars a month) to look for Livingstone.

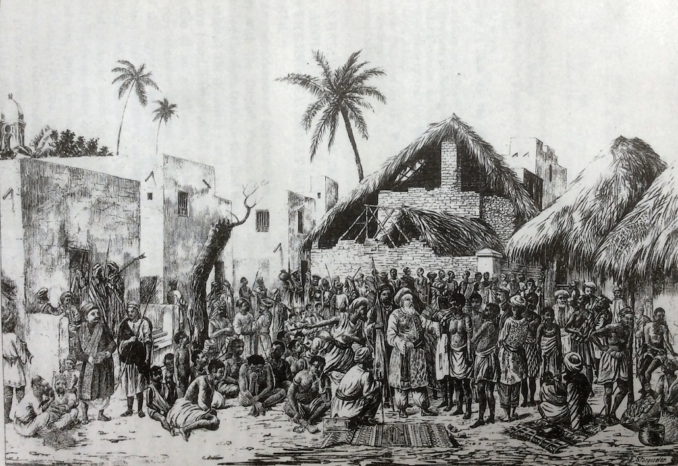

I wanted to learn more about that ancient rascal Tippu Tib, the greatest slaver of them all who carried the blood-red flag of Zanzibar as far as Lake Tanganyika and whose house still stands, haunted – so they say – by the ghosts of the 40 slaves who were buried alive in its foundations.

And perhaps, with a little luck, I might get to that romantic, palm-fringed bathing beach at Mangapwani, where the Arab dhows used to unload their slaves and hide them in underground storehouses.

Colonial Office photographic collection held at The National Archives

Instead I spent the best part of a morning listening to that old, old cry for independence and self-government.

The setting this time was an upper room in a cool, high-walled Arab house: my host the editor of the nationalist newspaper Mwongozi, which is published weekly in English and Kiswahli.

Mwongozi is one of 10 newspapers published on Zanzibar – which for an island not much bigger than the Isle of Man, with a population of around a quarter of a million, seems a fair amount of newsprint.

This newspaper and its editor, a cultured Arab who learned his English at Cambridge and his leader-writing from the Manchester Guardian, sternly and uncompromisingly advocates a policy of Zanzibar for the Zanzibari.

In this they undoubtedly have the backing of 44,000 Zanzibar Arabs and the bulk of the 200,000 Moslem Africans who, with 15,000 Indians and 200 Europeans, share the island’s simple, happy-go-lucky life.

That life on Zanzibar is simple and happy-go-lucky is largely due to the efforts of a handful of British civil servants, a fact that is rarely mentioned, I imagine, at the earnest political conversaziones.

What rankles, I think, in the minds of most orthodox Arabs, who are a proud, individualistic people with long memories, is the thought that the once-mighty Sultan of Zanzibar (represented by his Highness Seyyid Sir Khalifa bin Harub, GCMB, GBE, an old gentleman of great dignity and charm who has reigned in comparative peace since 1911) is now only a polite mouthpiece of the British Colonial Office.

After all, it is only 60 years since a British Fleet shelled Zanzibar Town and established a Sultan of our own choosing.

That was six years after Zanzibar became a British protectorate, partly to pacify the Anti-Slavery Society and partly through fear of the Germans, who were digging themselves in nicely on the mainland of Tanganyika just across the water.

Zanzibar Protectorate today comprises the islands of Zanzibar and Pemba and a strip along the coast of Kenya 52 miles long and 10 miles deep.

The Sultan’s red flag flies over the island of Mombasa, too; but it was leased to the Government of Kenya in 1895 at a rent of £ll,000 a year.

Since this modest rental includes one of the busiest ports in all Africa you can understand why Arab nationalists feel that more control should come from Zanzibar and less from Nairobi.

Having drunk far too much scented sherbet (this is officially a teetotal island: for serious drinking you need a liquor licence), I went and had a look at Zanzibar’s other problem.

This concerns the dried, unopened bud of the clove tree, Eugenia Aromatlea.

Thanks to the drastic enterprise of the Sultan Seyyid back in 1804 there are today something like 3½ million clove trees on Zanzibar and its satellite island Pemba.

Sultan Seyyid ordered plantation owners to pull down their coconut palms and plant cloves or lose their land

Eighty per cent of the Western world’s suet puddings are flavoured with cloves grown on this island. Certainty half the world’s toothache for the past hundred years has been soothed by a drop of oil distilled from Zanzibar clove-stems.

And no Oriental will smoke a cigarette that has not been slightly flavoured with clove.

Which at roughly six pounds of dried buds to the tree means a lot of cloves.

Since 1895 the two islands have been exporting an average of 8,500 tons of cloves a year. But whereas in 1953 the growers could expect to get £45 for 100lbs of cloves today they are lucky to make £11.

The reason for this is a strange new disease called “sudden death” which is playing havoc with the clove plantations.

So serious could the consequences be that a Clove Research Station has been set up to discover the cause of the disease, so far without success.

Dramatically, the scientists working on this vital research are housed in one of the most famous buildings on the island – the tall, white house, its red-tiled roof almost hidden among palm trees, which for several weeks in 1866 was the home of David Livingstone.

It was here that he came to fit out his last great expedition; and it was to this simple house that they brought his body from the other side of Africa, disguised as a roll of trade goods to protect it from harm.

You are conscious of Livingstone everywhere you turn in this ancient Moslem city; nowhere more so than in the cool quiet of Christ Church Cathedral – that lovely, gracious Mission church built on the very site of the terrible old slave market (the altar stands exactly where the whipping-post of the market once stood).

On the south wall there is a stained-glass window to Livingstone. And on the north wall, above the pulpit, you will see hanging there a cross made of wood from the tree under which his heart lies buried.

In the 1870s visitors to this exotic island of Zanzibar often remarked on the great number of white stones that covered the bottom of the bay.

They were not stones. They were the bones of dead slaves dumped over the side of Arab dhows which brought 20,000 of the poor wretches every year to the great slave-market.

Perhaps it is not too late to remind ourselves that it was a British Government, backed by the implacable will of the British people, which put a stop to that.

Jerry F 2021