Part Four of this Postcard from Romania revealed the joys of First-Class train travel through the ever-changing landscapes of this beautiful country, and a taste of Ursus, Romania’s most popular brew. We’d arrived at our AirBnB absolutely exhausted, after almost ten hours of jostling around in a train compartment and running the gauntlet organised by Romanian railway station taxi drivers.

Our first morning in Bucharest was somewhat brief, as we didn’t surface until almost midday. The bed we’d crawled into was wonderfully comfortable and we’d both just conked out. The first plan of the day was to find a decent coffee and a bite to eat, and then to get our bearings around the Old Town, less than half a mile from where we were staying. Off we set, in the beautiful May sunshine, far too warm to bother with a jacket.

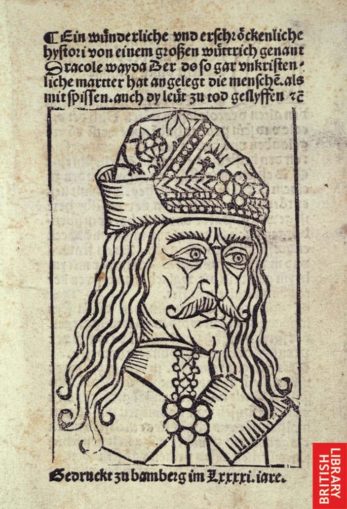

Romania’s capital is its largest city and straddles the banks of the Dâmbovița River (one of the Danube’s many tributaries). The city’s name derives from the Dacian word for ‘joy’, bucurie, thus Bucharest is the ‘city of joy’. A curious name, as not only did it become home to the former apprentice shoemaker turned Communist dictator, Nicolae Ceaușescu, but was originally developed in 1458 as the seat of the Voivode of Wallachia, a gentleman by the name of Vlad Țepeș (Vlad III, or Vlad Drăculea, also known as Vlad the Impaler).

British Library, Public domain

The principality of Wallachia, or Țara Românească as it was known, had been founded in the early 14th century by the Vlach ruler Basarab I, but was forced to accept the suzerainty of the Ottoman Empire in 1417. The city of Bucharest came into existence when Vlad III built a fortified stronghold to defend against Ottoman attacks during the Middle Ages. What remains of his Curtea Veche, the Old Princely Court, is the very first fortress built in Bucharest, the oldest mediaeval monument in the city, and the seat of many of Wallachia’s rulers.

Vlad had this fortress-residence constructed on a small hill in the town of Bucur, in the mid-15th century, in what was then an area of dense forest known as Codrii Vlăsiei. It was first documented as the ‘Citadel of București’ in Vlad III’s Charter from 20 September 1459. The charter concludes:

“S-a scris în septembrie 20, în cetatea București, în anul 6968 (1459) Io Vlad voievod, din mila lui Dumnezeu, domn”.

Wallachia was viewed as a buffer zone between the two principal Balkan powers, the Kingdom of Hungary and the Ottoman Empire. Add in tensions with the Transylvanian Saxons, and relations in the region were unstable to say the least. Not exactly popular amongst his foes, Vlad’s moniker, ‘the Impaler’, and his reputation for brutality was not unfounded. Stories about him had already begun to circulate during his lifetime, though his blatantly cold-blooded activities were likely to have been intended to a) solidify his rule, b) root out potential rivals for control of Wallachia and c) prove (in no uncertain terms) that he would deal harshly with his enemies.

In 1459, Mehmed the Conqueror (Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II) sent envoys to Wallachia in an effort to bring Vlad to heel, and to ‘request’ payment of a delayed tribute of 10,000 ducats and 500 recruits for the Ottoman forces. Vlad, however, wasn’t playing and refused to accept the suzerainty of the Ottoman Sultan over Wallachia.

Instead, as Antonii Bonfinii, the court Historian in Hungary detailed in his Historia Pannonica: Sive Hungaricarum Rerum Decades IV:

“Turkish messengers came to [Vlad] to pay respects, but refused to take off their turbans, according to their ancient custom, whereupon he strengthened their custom by nailing their turbans to their heads with three spikes, so that they could not take them off.”

That was undeniably one way to send a message. The exertions of the Sultan’s men, Thomas Katabolinos, lord of Porte, and Hamza Bey, the governor of Nicopolis, to set an ambush for Vlad in 1461 fared no better. The Ottomans were surrounded by Vlad’s men, and almost all of them were caught and impaled.

The Byzantine historian Laonikos Chalkokondyles remarked that:

“Vlad fought bravely, routed and captured him [Hamza], and killed a few of those who had fled. After capturing them, he led them all away to be impaled, but first he cut off the men’s limbs. He had Hamza impaled on a higher stake, and he treated their retinues in the same way as their own lords. Immediately after he prepared as large an army as he could and marched directly to the Danube, and crossed through the regions there by the Danube and the land that belonged to the sultan, killing everyone, women and children included. He burned the houses, setting fire wherever he moved. Having worked this great slaughter, he returned back to Wallachia.”

Nice bloke, our Vlad—a national hero in Romania.

Back to our visit, and although Bucharest’s Old Town doesn’t cover a massive area, it’s jam-packed with interesting things to discover. As we reached the outskirts of the Old Town, eschewing the omnipresent Starbucks, we noticed the Leonard Caffe, a little coffee shop in the perfect location overlooking Piata Unirii. Cosy and quirky inside, it’s like a small museum, chock-a-block with antique coffee-related paraphernalia with coffee roasters, grinders, percolators, pots and cups, all cheek-by-jowl with old telephones, pictures, books, and plants. An eclectic mix of weird and wonderful bits and bobs to look at whilst sipping an exceptionally good coffee.

© SharpieType301 2018

We chose to sit outside, in a small area separated from passing pedestrians on the broad pavement by a low fence decorated with hessian coffee sacks and troughs full of flowers. The sturdy tables are set on old cast iron sewing machine stands, adding to the eccentric appeal. Delightful, and with a plethora of wonderful-smelling coffees to choose from, it was perfect—just ready to sweeten our afternoon.

Thankfully, it also had a broad canopy as just when we sat down to enjoy our coffee in the afternoon sunshine the heavens opened, catching tourists and locals alike by surprise! Though torrential, the downpour didn’t last long.

© SharpieType301 2018

By the time we’d finished our coffee, and watched the world go by, the pavements were steaming and already drying out. We turned in to the Old Town towards the old Princely Court, past Manuc’s Inn (Hanul lui Manuc), the oldest traditional inn in Europe, where the hordes were already gathering to partake of the delights within.

At the height of the Ottoman supremacy, such inns (han) were commonplace in cosmopolitan towns such as Bucharest. The han, a.k.a. caravanserai, consisted of rooms or cells arranged around a courtyard, providing all the amenities a traveller required—secure lodgings for merchants arriving from distant lands, together with their servants, animals, and precious merchandise. Indeed, in the early 1800s there were close to 40 inns in Bucharest, which sits at the crossroads of major trade routes linking the cities of Central Europe with Constantinople.

Only one or two of the original inns remain. Hanul lui Manuc was built in 1806 by the Armenian grain merchant, diplomat and innkeeper, Emanuel Martirosi Mârzaian. Nicknamed ‘Manuc Bey’ by the Turks, he was one of the wealthiest and most influential men in the Balkans at that time. His two-storey inn, one of the largest in Bucharest, was one with a difference. Built in the Brâncovenesc style, with arched open galleries on both levels running around the large open courtyard, it initially comprised 107 rooms for offices or living, 10 storage sheds for merchandise, 15 cellars for wholesalers, 23 retail shops, 2 receiving rooms and a pub.

© SharpieType301 2018

Manuc’s Inn still houses a hotel—the oldest in Bucharest, and one which has a ‘hospitality clause’ in its contract. This dictates that any owner must maintain the same level of hospitality towards all travellers, giving each guest the honour he or she deserves. These days, there is also a restaurant, several bars, a coffee-house, and (on the street side) several shops and another substantial bar. It is the only shingle-roofed building to survive in central Bucharest. These were once commonplace, but this type of wooden roof was forbidden by the City Hall after the Great Fire of Bucharest (Marele incendiu din București) in March 1847 which destroyed almost 2000 buildings, around a third of the city.

Although a peep into the courtyard and the traditional Romanian menu was enticing, we decided against eating there as it was already busy and, being a tourist hot spot, is anything but inexpensive. Having meandered around the Old Town as the evening shadows lengthened, we chose a diminutive Asian café, Wok pe loc, for something to eat. Freshly cooked vegetables cooked in a wok, with meat and sauce of your choice. Simple, tasty and filling, it really hit the spot. Then, still tired from the previous day’s trek, we drifted in the direction of our AirBnB, picking up a few supplies on the way from a fabulous Carrefour that we got to know pretty well..

Oh dear, in the maze of small streets of the Lucaci–Traian neighbourhood (the old residential Jewish Quarter), where street names are sometimes a thing of myth, we promptly got lost! By the time we reached ‘home’ we were worn-out, footsore, grumpy and rather miffed that we couldn’t get the WiFi to work. First world problems, eh? Never mind, we were soothed to sleep by the strangely comforting susurrus of heavy rain on the tin roof just outside the bedroom window.

Up with the larks the next morning and ready for a day of exploring… once we’ve managed to master the elderly and cantankerous gas cooker to scramble the eggs we’d bought for breakfast. We managed that, but totally failed to persuade the grill to light. OK, no toast, but fed and watered, off we set, attempting to follow the Rough Guide map to get us to the Old Town without a repeat of the previous night’s mystery tour. OK, that didn’t work. Somewhat bamboozled, we didn’t end up where expected, but stumbled across a Tourist Information office with a lovely chap who provided a decent map and lots of advice. Pure serendipity.

As we headed along Lipscani Street we passed the entrance to the beautiful Cărtureşti Carousel bookstore, possibly the most magnificent shop I have ever seen, so couldn’t resist going in. I had read about it, but what I’d read just didn’t do it justice. It has been claimed the name translates as ‘the Carousel of Light’, and you can certainly see why.

Designed by architect George Matei N.B. Cantacuzino, and constructed in 1860, the property was bought by Nicolas Chrissoveloni in 1903 to house the family’s banking headquarters. The eponymous Chrissoveloni Bank had been founded by Nicolas’ father Zannis, a banker-aristocrat of Greek origin, in Constantinople in 1830. Moving to Romania in 1848, he merged with another bank, and by 1889 the dynasty’s banking and industrial empire was well-established in Bucharest. The building on Lipscani Street remained in the Chrissoveloni family’s hands for nearly four decades until it was confiscated and nationalised during the Communist era in the late 1940s. No longer operating as a bank, the building was turned into a men’s clothier, then a department store called Familia. After the collapse of the Communist regime, the building was abandoned and fell into disrepair until it was rescued by Jean Chrissoveloni, great-grandson of the first owner.

© SharpieType301 2018

The elegant 19th century art nouveau building is a glorious, bright space over six floors, including sinuous mezzanine balconies weaving between the building’s elaborate Corinthian columns, with a glass elevator and spiral staircases. Now a booklovers paradise, it’s a Bucharesti institution, from the basement’s multimedia area to the first-floor gallery dedicated to contemporary art and exhibitions, and upwards to a light-filled bistro café (sadly not open) on the top floor under the massive, pitched glass skylight.

They even have a resident cat! You might think that he’d be quite fed up with the number of people who stop to pet him, but he’s always ready for a cuddle.

© SharpieType301 2018

We were heading for Piața Revoluției (Revolution Square) and the nearby museums and galleries. Mr S. has often (yawn) regaled me with tales of his first time in Bucharest, a matter of weeks after Ceaușescu’s bloody end. His wife at that time was a chef and carried with her a very full knife-roll. They were on their way back to the UK following a couple of years working on Crete. In his carry-on rucksack Mr S. carried a large Swiss Army knife. They fully expected the knife-roll to be confiscated by customs but hoped the pen-knife might be missed. Before they left Crete they’d been told that the regular customs people had been turfed out and their place taken by ‘revolutionaries’. That turned out to be true but the knife-roll wasn’t even opened – the pen-knife, however, went straight into the pocket of the ‘customs man’.

© SharpieType301 2018

Once the dynamic duo found the city centre they looked for cheap accommodation and came across shop offering just that. It turned out that one of the first things the new ‘government’ wanted to do was to encourage tourists to return and were using all sorts of empty property to let to them. Mr S and his wife were taken to a huge government building over-looking the newly re-named Piața Revoluției – the exact same square where much of the fighting took place. The building had, until very recently, been the headquarters of the main communist organization, The Central Committee of the Romanian Communist Party. The top couple of floors had been occupied by Romania’s ambassadors, including the ambassador to Brazil who, quite sensibly, stayed overseas well away from his apartment while it kicked-off back home. When Mr S pointed out the damage high up on the walls of the rooms over-looking the square, the ‘travel agent’ calmly explained, ‘bullet holes’.

Before we reached Calea Victoriei, to turn right to reach the Square, we heard an enchanting melody drifting along the street towards us… Opposite the imposing and massive building which houses The National Bank of Romania (Banca Națională a României, BNR) was a street musician. The man was playing the țambal (the Romanian hammered dulcimer, baby brother to the cimbalom) striking two curved sticks, with cotton-wound tips, against the strings stretched across the top of the sound box.

© SharpieType301 2018

These delightful instruments developed from the Persian santur which became popular in many European countries in the 11th century. A haunting sound, but the gentleman playing had a beaming smile and appeared to be having the time of his life.

A few more detours (the architecture in Bucharest is quite stunning) including being captivated by the Pasajul Victoria, a popular arcade covered with colourful display of umbrellas…

© SharpieType301 2018

… and we finally reached Revolution Square. Mr S said that the trees had not been there when he stayed there. Neither had the statuary, including the bronze sculpture of Iuliu Maniu, co-founder of the National Peasants’ Party and three-time Prime Minister of Romania. Maniu was sentenced to life imprisonment with hard labour at the notorious Sighet Prison by the Communist Regime, and this bronze depicts him as a broken man, but one with an unbreakable spirit. As we passed the bronze and approached the building’s entrance we looked up, above the balcony upon which Ceauşescu’s famous last speech was given. It is still possible to make out the bullet holes.

© SharpieType301 2018

There are a number of other statues in the square, but the pillar faced with pieces of broken mirrors was not one to brush against accidentally. Perhaps the most striking is the Memorialul Renaşterii (The Memorial of Rebirth, sometimes referred to disparagingly as the ‘Potato on a Stick’) which honours the victims of the Romanian Revolution of 1989. A 25-metre-tall marble spike, on which a tangled, bronze openwork structure is impaled (hmmm, we’re back to Vlad, it seems), it certainly stands out. I can’t say I liked it but, interestingly, it’s still possible to see the remnants of the blood-red paint thrown at the ‘potato’ in 2012 which dripped down the spike. Vandalism or no, it strangely put the finishing touches to the symbolism of the monument, and has never been erased by the authorities, who cite the inaccessible height being too great an obstacle. Yeah, I’ll believe them.

© SharpieType301 2018

By now, we’d done a fair amount of walking. We were hungry too, but we didn’t have to go far. Just around the corner, on Strada Academiei, we spotted the wonderful Ciorbărie Academiei. A tiny place with just a few stools at a rough wooden bench by the window, but the most enticing aromas and a steady stream of smartly dressed take-out customers (from local offices, perhaps). The name of the shop gives the game away. It sells ‘ciorba’, soup, (the name comes from the Persian word شوربا). A must-try for everyone visiting the city. Only a small menu, but one which changes daily, the soups are freshly made and served with a hunk of hearty wholemeal rye and linseed bread. We both chose the Romanian tripe soup, ciorbă de burtă, rich with strands of deliciously silky tripe, creamy and luscious.

© SharpieType301 2018

Cheap as chips (actually cheaper), this was the perfect option for a tasty, healthy, and filling lunch. Refreshed and happy, off we head anticipating the enticing delights of the Muzeul Național de Artă al României, particularly keen to see the collection of Romanian Mediaeval woodcarvings, embroideries, manuscripts, icons, murals, and silverware, some dating back to the 14th century. But we find it closed—dammit, it’s Monday, so it won’t be open tomorrow either! OK, another day then.

We head back towards the Jewish Quarter, not far from where we are staying. Bucharest’s Jewish district was centred around the Templul Coral Synagogue, one of only six of some eighty Synagogues still standing today in the capital, of which only three still hold religious services. This building, faithfully modelled on Vienna’s exquisite Leopoldstadt-Tempelgasse Great Synagogue which was destroyed during Kristallnacht in November 1938, was one we were keen to visit. That’s closed too, though it is supposed to open on Mondays. Fine, we’ll come back tomorrow.

Onwards we trogged, through the heat of the afternoon, to visit the Jewish Museum in the former Templul Unirea Sfântă Synagogue, a place of worship for the Tailors’ Guild, and one of only a handful in Bucharest to survive World War II. Oh boy, we did not believe it—it’s closed. This time for renovation work on the building, a fascinating mixture of Moorish, Romanesque and Byzantine styles, and not just today but for the foreseeable future too (in fact it took more than another year). Scratch this one off the list.

We used the map we’d picked up in the morning to attempt to find the Great Synagogue. Also called the Great Polish Synagogue, it was built in the mid-1840s by Ashkenazi Jews who’d fled Ukraine and Poland as a result of the Cossack uprisings and, at that time, was the largest synagogue in Bucharest. It is home to the Holocaust Museum and, having double checked, we knew it was open on a Monday. Except that by the time we finally found it, having become completely lost in the labyrinthine desert of multi-story utilitarian socialist concrete apartment blocks (hmmm, maybe that map wasn’t quite as good as we’d thought), it’s just a few minutes after 3 o’clock and it was closed. It really isn’t our day! Damn, maybe we should have hired a car to get around, but the luxurious prestige model we contemplated was fitted with those uncomfortable low profile tyres, so the chap from Europcar missed out on his commission.

© SharpieType301 2018

By now tired, footsore, sticky, thirsty and not a little cranky, Sharpie rebelled and insisted we sat quietly in the square for a while. There, we contemplated the striking memorial to the one hundred and twenty-five Jewish men, women and children martyred by the paramilitary ‘Iron Guard’ Legionnaires during the horrific three-day Bucharest Pogrom of January 21-23, 1941.

© SharpieType301 2018

The memorial is simple but extremely moving—a near-black marble obelisk on a stepped base, pierced on one edge by a Star of David, from which exudes a sinuous flow of deep-red marble, like blood or tears, curving down to the base, over the steps and across the square. As we rested, a minivan drew up and a group of people got out to examine the memorial, and the nearby inscriptions. More than one was in tears as they took photographs and read the wording at the base of the memorial, the final words of which are:

Their memory shall be blessed! We will not forget!

A little despondently, we wandered back towards our apartment, through the remnants of the former Jewish District (which once spread from Piata Unirii through Văcărești and Dudești towards the Dristor neighbourhood of Bucharest). Trading and craft once thrived in the quarter. In 1940, Văcărești and Dudești alone was home to forty-seven delicatessens and spice shops, thirty-three haberdasheries, twenty-five tailors, twenty hairdressers/barbers, twelve butchers, eight grocers, seven shoemakers, four glassware shops, four hat makers (one of whom is still there), four tinsmiths and a multitude of other craftsmen.

In 1947, the city’s Jewish population, which admittedly had increased with an influx of refugees from concentration camps, stood at an estimated 158,000, of a total population of c.650,000. Today, there are thought to be merely 2,000, from a city-wide population of 1,794,450.

What happened? Emigration to Israel under the privations of the communist regime was an important facet, but a much greater impact was felt through Nicolae Ceauşescu’s ‘systematisation’ policy to build a kind of brave new world. This prompted one of the largest urban destructions in peacetime in recorded history. His convenient excuse for initiating this was the 1977 Vrancea earthquake, a 7.2 magnitude quake which damaged or destroyed nearly 33,000 buildings, killing around 1,400 of the city’s people and leaving 34,500 families homeless. Rather than repair, Ceauşescu had over three-square miles of historic Bucharest, including almost of the Văcărești neighbourhood, with churches, synagogues and other irreplaceable buildings, levelled.

Here was his golden opportunity to start Building Back Better, one might say. The chance to create the Bulevardul Victoria Socialismului (Victory of Socialism Boulevard, at over two miles long) to rival to the Avenue des Champs-Élysées in Paris was seized eagerly. Along its length and perpendicular to it, high-density standardised apartment blocks were erected. The demolition also made way for his grandiose Centrul Civic and, at one end of the Boulevard, the Palatul Parlamentului (the heaviest and most expensive administrative building in the world), symbolising Ceauşescu’s absolute power.

After Cluj, the city seemed hectic, dirty and a little unfriendly. It was good to see where Mr S stayed after the fall of communism, and it’s an interesting city. But it’s not a comfortable one—not unlike London in that respect—Bucharest has elements of the Good, the Bad and the Ugly. For some, it is a hell on earth. Beneath the city’s beautiful streets is another world, an underground network of sewers, home to a close-knit group of marginalised individuals—the ‘Mole People’. The 1989 fall of Nicolae Ceausescu’s dictatorship, led to all Romanian orphanages being closed. Thousands of children, born at a time when both contraception and abortion were forbidden by the State, were abandoned. These lost souls had no families, no money, no belongings and nowhere to go. Some took to the sewers near the railway stations, like something out of Jeff Wayne’s War of the Worlds, where at least there was shelter and heated steam pipes to keep them warm. They’ve been there ever since. Drug addiction, malnutrition, HIV and STIs are rampant. Once given food by local charities, they now have almost no one to turn to for help. The police don’t have much sympathy for them, periodically raiding the sewers and evicting the residents and the stray dogs who live with them. Without support, they simply move on to another underground ‘home’.

I felt a little sad as we made our way back to the apartment. Post-systematisation, streets which once reverberated with the sounds, sights and smells of Jewish life no longer exist. Sadly, only a handful of the buildings marking the old Jewish district have resisted the ravages of time and a madman’s architectural fairy-tale. Their faded glories are pretty extraordinary and, thankfully, some are being lovingly restored. Although it’s great to see what they might have looked like in their heyday, all too many have been left to rot. As we walked through the streets, a chorus of dogs was howling. Somehow it seemed a fitting soundtrack to this day.

© SharpieType301 2018

We planned to eat at a Romanian restaurant that evening, La Nenea Iancu on Strada Romulus, just a hop, skip and a jump from the apartment so minimal walking. We’d been told it was not cheap but was very good. For a Monday, it was surprisingly busy, and the clientele appeared pretty well-heeled—for those of you who know Cardiff, the Pontcanna Taffia. I ordered a glass of the wheat beer produced for them by the German Memminger brewery, Nenea Iancu Bere Albă Nefiltrată Din Grâu. Brewed to a traditional recipe involving natural fermentation, compliant with the 1516 Reinheitsgebot (German Beer Purity Law), for a beer from a large brewery it was surprisingly good.

There was jazzy Caro Emerald ‘A Night Like This’-style music, and fantastic people-watching. A group of about ten immaculately dressed men came in on a drift of aftershave and took their places at a long table a little way from us. They started their evening with a round of something clear and potent looking in small shot glasses. The deep red wine then poured into the gorgeous, globular glasses on their table looked thick, dark and expensive. Then the food began to come out – they’d ordered sharing platters to start—cured meats (Romania being a meat-lover’s paradise), cheeses, plus others we couldn’t quite identify. When their main course (with the wine flowing freely) arrived, it looked spectacular. Two or three mixed meat platters (which looked so good we’d decided we were going to try one), a pile of chicken, at least two of the biggest pork knuckles I’ve ever seen and a plethora of small dishes of who knows what.

We had our own meaty sharing platter for two and a mixed salad. Wow! When it arrived, it would easily have fed four: two succulent pork cutlets, a couple of hefty, delicious-looking coarse sausages, four mici (or ‘little ones’, pretty much the national dish, a traditional delight made from beef, lamb and pork with garlic and spices), a pile of thin spicy sausages, two sizeable wedges of Mămăligă cu brânză (Romanian baked polenta with cheese), a bundle of tangy pickled cucumber, and a small pot of firey mustard which I think might have been mixed with horseradish. And that’s before we even get to the beautiful fresh salad of ripe tomatoes, cucumber, red pepper, red onion and a crumbly, salty white cheese on a bed of leafy greens… oh, and a pile of home cooked fries and a basket of warm Kaiser rolls.

© SharpieType301 2018

We were not going to go home hungry and even pigged out with a dessert; a decadent tower of cinnamon-spiced baked apple and sultanas, with layers of a nutty, buttery crumble and a ball of creamy vanilla ice-cream on top, all drizzled with a caramel sauce. There was even the mythical cherry on top! This one was garnet-dark, luscious, and marinated in something decidedly alcoholic. Mr S pronounced it the best dessert he’d ever eaten.

The men at the long table were still at it when we finally decided it was time to waddle home, having shelled out the princely sum of 170 lei (about £34). Expensive? Pah! I dread to think what that would have cost in Blighty, even if we could find something half as good.

The next morning, we headed back towards the Great Synagogue, along some of Dudești’s smaller old streets (thankfully, unlike some of the neighbourhoods nearby, most of Dudești escaped Ceauşescu’s ‘systematisation’ demolition). We passed under numerous deliciously fruiting mulberry trees. Interestingly, the name of the neighbourhood derives from the Romanian word dud, meaning ’mulberry tree’. We passed a pleasant-looking school (very neat kids), and old buildings with luxuriant, overgrown gardens hinting at their much grander past. Though run down now, I fell in love with this neighbourhood.

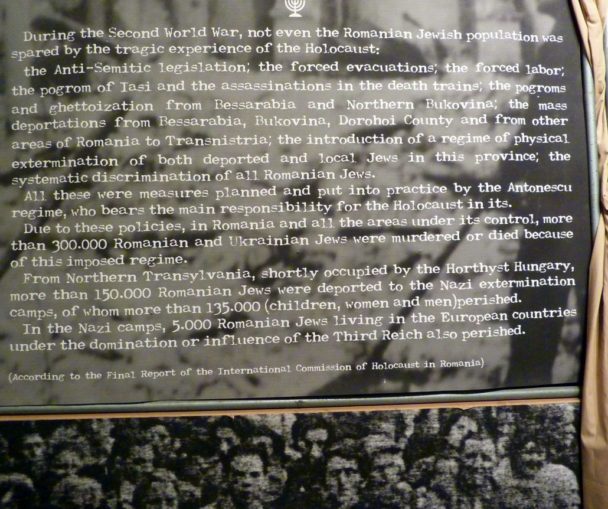

Our destination was the Holocaust Museum, and we were quite surprised to find that it was free to go into the Synagogue. As we entered our names in the visitors’ register we were approached by a very elderly gentle man, the museographer, who acted as our guide (his English was heavily accented, and obviously not his mother tongue, but superb). I was slightly concerned about him as his balance was not perfect so was grateful when, as we went down a couple of steps, he graciously took my arm. As he escorted us he spoke slowly and carefully so we understood what was important for us to know. He explained the building and the panels around the walls which tell of pogroms, assassinations, and the deportation of Jews right across Romania. He left us then to explore the museum at our own pace.

© SharpieType301 2018

The building itself is beautiful and was once one of the ‘richest in Bucharest’, with electricity and central heating already in place by 1915. Completed in 1847, it’s the oldest of all the remaining synagogues in Bucharest—although the Jewish presence in Bucharest dates back to the 1500s, it took hundreds of years before the community was granted the right to build a Synagogue. Richly decorated with a vaulted ceiling, lovingly painted and gilded in the Rococo style by Ghershon Horowitz in 1936. In the centre hangs a magnificent circular chandelier, donated in the 1920s, with smaller chandeliers under the balconies casting a welcoming, gentle light. The building was restored in 1945 as it suffered during the 1940 earthquake, then was more extensively damaged at the hands of the ‘Iron Guard’ Legionnaires in 1941.

But the most important, and disturbing, element of the Holocaust Museum are the panels around the walls.

The Jewish community in Romania is one of the oldest in Europe. For centuries Jews lived and prospered in the land which is now Romania. Settlements dating to 87-107 AD have been found in Transylvania, including Tălmaci (Thalmus) founded during the reign of the Dacian king, Decebalus. Other settlers came with the Roman army, as it swept through the region. Inscriptions and coins have been found in Sarmizegetusa and Orşova.

The panels do not cover this aspect of the history, but instead start with a display showing proud Jews who fought for Romanian independence during the 19th century, despite not being granted citizenship. Not until 1864 were Romanian-born Jews granted suffrage (so-called ‘little naturalisation’) by some, but not all, local councils.

By 1904, the country’s Jewish community had seemingly prospered. They comprised a good proportion of Romania’s middle-class. Some 38% of doctors in Romania were Jewish. They were merchants, bankers, factory owners (in the glass, metal, wood, furniture, clothing and textile industries), they were craftsmen (engravers, tinsmiths, watchmakers, bookbinders, hatmakers and upholsterers). All this at a time when, prior to World War I, the country’s industry was not highly developed—nearly 85% of the Romanian population were farmers.

Outwardly, a golden façade, but behind the scenes the situation worsened. As we traversed the Museum’s wall panels, following the timeline of events, the documents and photographs began to tell an increasingly grim tale.

Once considered Romanian subjects, even if not citizens, Jews were pronounced ‘foreigners’ and forbidden to be lawyers, teachers, chemists, stockbrokers, railway officials, to serve in state hospitals, or sell ‘products of the state monopoly’ (e.g., tobacco, salt, alcohol). In the lead up to WW I alone, as persecution increased, roughly 70,000 Jews left Romania.

Socio-economic and political tensions after WW I intensified anti-Semitic feeling, propagating further hostility. Romanian authorities actively persecuted the Jewish minority in Bessarabia on the eastern borders (accusing them of supporting Soviet communism), and in Transylvania (simply for being identified with former Hungarian rule). By the late 1930s economic persecution began to bite in earnest, with Jews expelled from commerce and industry as the Nazis moved eastward. In 1940 King Carol II was forced to abdicate, and General Ion Antonescu came to power.

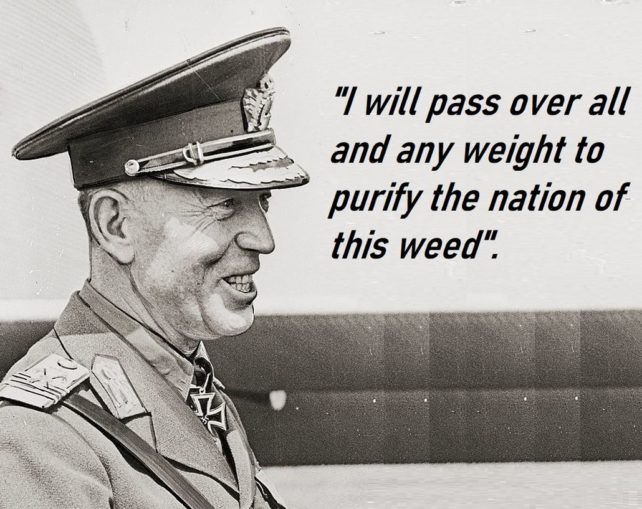

He formed a fascist government, a somewhat uneasy political alliance, with de facto co-leader Horia Sima. Sima’s paramilitary ‘Iron Guard’ Legionnaires opposed communism and capitalism and their ideology was xenophobic, ultra-nationalistic, and extremely anti-Semitic. Conducător Antonescu declared Romania a Nationalist-Legionary State, and the regime’s ‘legionary police’ was organised along Nazi lines with the aid of Hitler’s S.S. (Schutzstaffel) and S.D. (Sicherheitsdienst). Romania formally joined the Axis alliance in 1940 and, hoping to preserve its borders, Romania, which had not been invaded by the German army, became a satellite of Nazi Germany.

Citizenship was immediately revoked, and a harsh period of anti-Semitism ensued. Here, the information displayed by the Museum’s wall became darker still. Jewish-owned shops and businesses were confiscated, industrial and commercial enterprises were surrendered to Legionnaires as the Iron Guard arrested and tortured the owners, forcing them to sign certificates of transfer.

© SharpieType301 2018

Sima initiated a series of political murders (killing 64 political prisoners in Jilava) in retribution for the earlier assassination of his Iron Guard compatriots, further damaging his relationship with Antonescu. Then in January 1941, in an attempted coup, Sima’s Legionnaires rebelled against the Antonescu government.

Pursuing his anti-Semitic agenda, Sima also instigated brutal pogroms. During the Legionary Rebellion, riots lasting for three horrific days specifically targeted the Jewish community. The pogrom staged in Bucharest was brutal and sadistic. United States Minister to Romania, Franklin Mott Gunther, looked on with revulsion as the Iron Guard committed appalling atrocities, documenting an incident at the city abattoir, where Jews were forced to crawl into the building like animals before being butchered. Gunther observed:

“Sixty Jewish corpses were discovered on the hooks used for carcasses. They were all skinned . . . and the quantity of blood about was evidence that they had been skinned alive”.

Some of the victims, amongst whom was a five-year-old girl, had been hung on slaughterhouse hooks, tortured, and their intestines hung around their necks in a monstrous parody of shechita, kosher slaughter practices.

However, the brutality was not confined to the Legionnaires, who were joined in the terrors by staff from the Bucharest police force, workers’ and student organisations. Official reports put the Jewish death toll at 127, but photographs from the period suggest that might well be an underestimate. Reports from the Jewish Telegraphic Agency (which can be read online) from around the 27th to 31st January 1941 put the numbers far higher.

Yet this was only the beginning, as the panels around the Museum’s walls graphically describe. Just few months later, in the heat of June 1941, the Bucharest atrocities paled in comparison with events in the second largest city, Iaşi (sometimes called Jassy).

This time, the barbarous pogroms commenced under direct orders from Ion Antonescu who, only five days after Romania’s entry into WW II, phoned the commander of the Iași garrison, stating his desire to ‘cleanse Iași of its Jewish population’. Newly released members of the Iron Guard, imprisoned since the failed January coup, were enlisted under police command and armed. Rumours were spread that the whole of the city’s Jewish community were Communist sympathisers, working for the Soviets. With this ‘excuse’, soldiers, police, and mobs began to massacre the city’s Jews and plunder their possessions—at least 8,000 were brutally murdered in the first wave of violence alone.

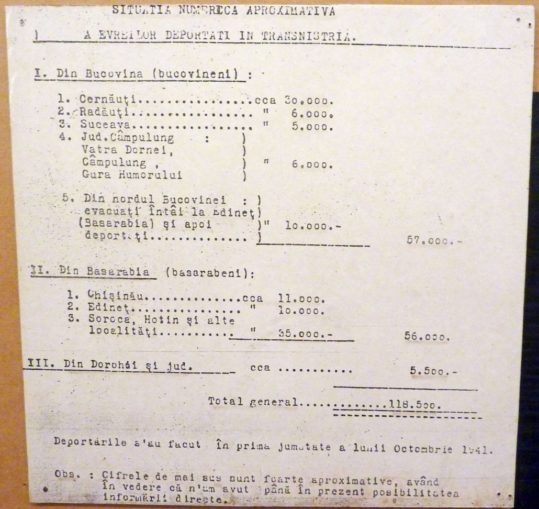

Any who survived the Iaşi massacre were forced into columns and herded to the railway station to be loaded into two ‘death trains’: cattle wagons, still with a layer of cow-dung and lime powder on the floor. Up to 150 people would be thrust into a single wagon. Barely able to stand, many already severely injured, tormented by thirst, the heat, and lack of air (the small windows were deliberately sealed shut), the trains travelled back and forth across the countryside for eight days, stopping only briefly for bodies to be thrown from the wagons.

State Treasury of Poland, Public domain

The evidence of these inhuman events is distressing, and I found it increasingly difficult to see for the tears streaming down my face. In addition to the information held by the Museum, tens of thousands of pages of documentary evidence and over a hundred photos taken during the pogrom in Iaşi between June 26th and July 2nd, 1941 (likely by the Special Intelligence Service) have been made available to the public through a website ‘Pogromul de la Iasi’. It’s deeply disquieting but provides a clear indication of Antonescu’s intentions. He’d made his views unambiguous from the outset, as just weeks after declaring his Nationalist-Legionary State, he pronounced that solving the ‘Jewish Question’ was imperative.

The Iaşi pogroms and death train transportations were just part of his policy of ‘clearing the land’, his euphemism for ‘the final solution’. The International Commission on the Holocaust in Romania states that up to 14,850 Jews (or one third of the Jewish population) were massacred in the pogrom or its aftermath, and from 1941 onwards, things only got worse.

It was at this point that I realised that the lovely gentleman who had welcomed us so kindly would have lived through the dreadful events we were seeing through the exhibits, experiencing this at first hand. Without being sure of his age, he would likely have been a child or teenager.

A keen Axis participant, Romania joined the invasion of the Soviet Union, committing more troops to the Eastern Front than any of Germany’s allies, fighting in Ukraine, Bessarabia, Stalingrad and elsewhere. Romania reannexed Bessarabia and northern Bukovina then, following the conquest of Ukraine (by German and Romanian troops) Romania was granted the region between the Dniester and Southern Bug Rivers, where they instituted military rule. This was a ‘second prize’ of sorts for Antonescu, awarded as a substitute for Northern Transylvania, which had been assigned to Hungarian Regent Miklós Horthy’s kingdom following the Vienna Diktat of August 1940. The recently acquired Romanian-controlled district was given the name ‘Transnistria.’

© SharpieType301 2018

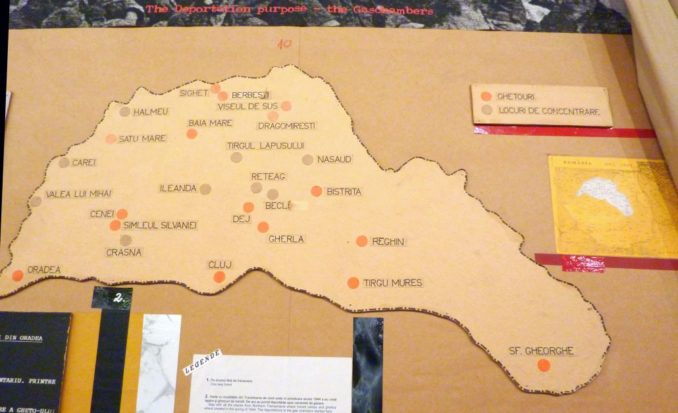

Romanian forces, and troops were responsible for the persecution and massacre of between 280,000 and 380,000 Jews, who were murdered or died across the Romanian-controlled territories. If they were not killed, they were concentrated into ghettos (which Antonescu’s government deceitfully referred to as ‘colonies’) from which they were dispatched to Transnistria, to labour and concentration camps built and run by the Romanian authorities. Shown on the map below are simply those camps and ghettos in Transylvania.

© SharpieType301 2018

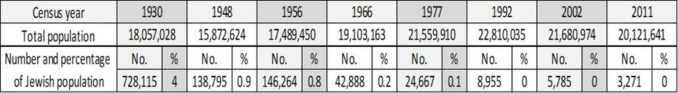

The Romanian Holocaust was the most vicious and deadly outside of Nazi Germany. Not a single region of the country escaped the horrors. Looking at census figures for the Jewish population against the population of Romania as a whole, the changes are striking and the effects of WW II (and ongoing persecution under the Communist regime) create produce an uncomfortable statement.

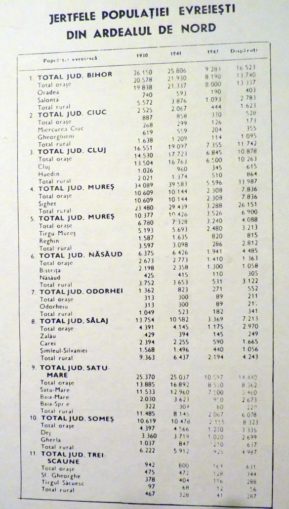

Examining the Museum’s display of figures for Northern Transylvania’s Jewish Population, county (Jud. or Județ) by county, provides a snapshot of the effects of the Holocaust at a more local scale. The document shows numbers before, during and after WW II, both in the cities (orașe) and rural areas. The final column gives the numbers ‘missing’.

© SharpieType301 2018

This museum makes for a harrowing visit, and the overwhelming question it left me with was ‘why’. Something which started as land and property grab had so rapidly turned into wholesale genocide. The displays really bring home the meaning of ‘inhuman’. How could one section of a population turn upon another so overwhelmingly?

Its focus is on the Jewish community, but they were not the only people to suffer. The Roma (Gypsies) were also regarded as `non-persons,’ of `foreign blood,’ and `work-shy’. As such, they were viewed by Antonescu’s regime as disposable, Unnütze Esser (‘useless eaters’). Whilst the authorities didn‘t methodically exterminate the Roma, they were singled out for racial persecution. The military and police officials deported around 26,000 Roma, half of whom were children. Largely from Bukovina and Bessarabia, but also from Moldavia and Bucharest, they were shipped to Transnistria (southwestern Ukraine) when the region was under Romanian control. Women and girls faced the constant fear of rape, while thousands of deportees died from disease, starvation, and brutally sadistic treatment.

As we came to the end of our time at the Holocaust Museum, we spoke again to the elderly museographer and left a generous donation to help with the Museum’s upkeep. He thanked us for taking the time to visit, and for trying to understand a period of history with which we have no personal knowledge but must never be forgotten. I cannot begin to envision the memories he must carry with him. Perhaps learning about the events which took place, here and in neighbouring countries, should be compulsory. To quote the philosopher George Santayana:

“Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

A sombre note to end on, but the next episode will, I promise, be more uplifting as we explore more of this extraordinary city. For now, we just needed to stop, sit quietly with our thoughts over a coffee, and count our blessings.

© SharpieType301 2021

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file

Audio Player