Newport in South Wales sits astride the mouth of the River Usk and so its history has long been connected to maritime commerce, with wharfs recorded lining the banks of the river since the 1500s. (In 2002 a mediaeval ship dated to around 1465 was unearthed during excavation work.)

Shipping movement on the Usk was however heavily restricted by the river’s tidal movement (the 2nd largest in the world). With the coal industry bringing increasing river trade, in 1835 the decision was made to build a floating dock. Not perhaps unsurprisingly called the Town Dock, it opened in 1842, although within a few years it had become overcrowded, and with the extension, built in 1858, also soon proving inadequate, a move was made to the new Alexandra Dock which opened in 1875.

The rapid increase in coal export (between 1877 and 1881 coal exports doubled from 610,000 tons to 1,200,000 tons) meant that this dock too, was extended into what would be known as the South Dock. The new dock significantly increased trade capacity but ships still had to pass through the old entrance from the river Usk and this was causing a problem.

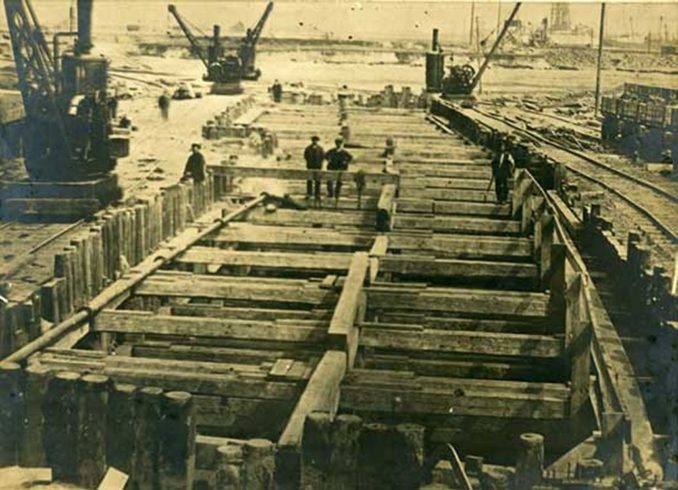

A new lock entrance was therefore needed; at 1000ft long and over 100ft wide, it was billed at the time as the second largest in the world and allowed access direct from the Bristol Channel. It was during this construction, in 1909, that the largest peacetime disaster in the history of Newport occurred.

Friday 2nd July 1909

At around 5.20pm on a hot afternoon, two gangs of men were working on a huge trench – what would be the west wing wall of the lock into the South Dock. The trench was around 240 feet in length, up to 45 feet deep and surrounded by cranes and railway wagons; concreting was scheduled to start that evening.

© newportpast.com Used with permission

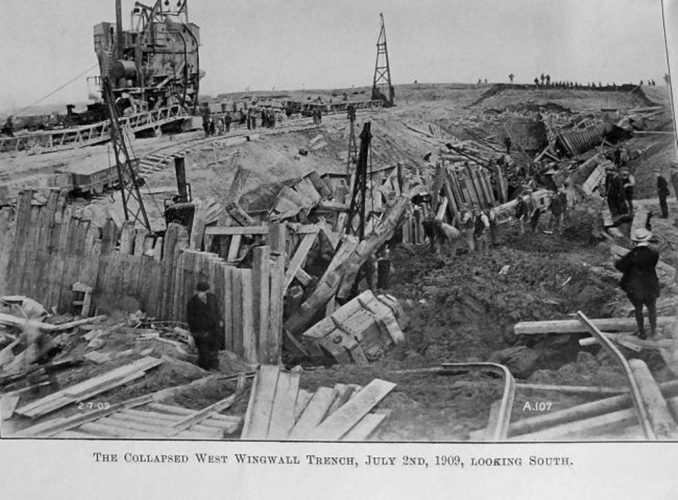

Some 50 men were gathering up their tools as they prepared to leave for the day and were making their way to the three access ladders, when, with a ‘sudden groan and a rapid series of cracks’, the entire length of the west wall gave way, snapping the 14inch supporting timbers ‘like matchsticks’ and pitching many of the surrounding cranes and wagons into the trench.

Men who were leaving the trench or were stood at the trench sides were either thrown back in or dragged in with the collapsing timbers.

A Mr Faris, one of the engineers, commented at the subsequent Inquest, ‘The timber seemed to move up in the middle, and the whole thing went with practically no warning at all. As soon as I saw the timber beginning to move I gave a shout of warning and a number of men climbed up the ladder and got out. I was standing by the side of the trench and was thrown down. I alerted the railway drivers to sound their whistles to summon help.’

Other eye witness statements:

‘’There was a sudden overflow. It was as if the earth had opened and swallowed up everything, cranes, wagons, everything.’’

‘’The timber groaned and cracked and then gave way, the sides closed in ….’’

‘’We heard timber crash, and we sank with the sinking sand and mud but we were on top so we weren’t buried….’’

‘’The timbers rose like a camel’s back and then collapsed like a concertina….’’

‘’The whole of the timbering collapsed and fell together like matchwood….’’

‘’It sounded like an explosion……a crash, a collapse and dust rose like smoke. It was all over in about two seconds…’’

‘’Men who were at the bottom were caught like rats in a trap ….’’

The steam whistles were heard for miles and all over the docks workers ran to assist. They all knew what a continuous whistle meant, but nothing could have prepared them for the sight that confronted them.

Workers began to form gangs to rescue the trapped men who could be heard crying for help. Many volunteered their services, but the need was for ‘trenchmen’ and those familiar with timber work.

Fire was an enormous risk as the fallen cranes had emptied their boilers and burning coals, and so the first task was to ensure that no more coals fell into the trench that could possibly set the timbers alight.

One man, a young crane driver was visible in the debris of timber, wagons and cranes; he was pulled free already dead, the first of the many victims.

One of the problems the rescuers faced was the fact that there was no way of knowing just how many workers were trapped among the timbers. It was the end of shift; some had already gone home, many of the workers were itinerant only known by nicknames and some hadn’t even turned up for work that day.

One thing everyone did know – those trapped and their rescuers alike – was that the greatest danger came from the tide; it was coming in. Its progress was only held back by a temporary dam near the head of the cutting. A gang of men were tasked with strengthening this and the extra pumps needed were called for; but rescuers knew they were in a race against time.

In the trench

Dr Hamilton, a local GP was the first Doctor on the scene. Between 11 o’clock and midnight, a 16 year old, Albert King, was seen alive but held fast by a huge beam of timber on his arm. He was passed a drink of brandy by Dr Hamilton and given some cigarettes as he pleaded for his hand to be severed ‘I wouldn’t mind’ he is reported as saying…….’If I had a hatchet, I would cut it off’.

Then the timbers shifted and he was lost from sight.

* * *

J. Townsend, ganger to the contractors, reported ‘I helped George Champion (foreman) to sink a pit behind the collapsed trench where a man named [William] Downton was taken out. We got out two men before we got to Downton. We had to cut off two piles and draw three before we could get at him, and this was very risky work. We worked there all night and next morning until doctors (surgeon Drs Cook and Crinks) cut off Downton’s legs.’

Downton was lifted to the surface to a waiting ambulance but died on his way to hospital.

* * *

At around 10.30pm, Albert Pullen, a workman on the dock, had managed to grope his way in the dark to two trapped men.

Pullen lowered a candle down to them and asked their names.

‘Jim Brown and Nobby, give us something and we’ll dig ourselves out’.

At that moment the timbers moved forward and Pullen was forced to jump clear.

* * *

Some had a very lucky escape:

According to the South Wales Press, the navvy John Knight, who was working at the bottom of the trench, was ‘just about to light his pipe when the disaster occurred’. As other men ran for the ladders he remained perfectly still, in shock. After ‘about an hour’, when he detected no more movement around him, he lit a match – he was still clutching them in his hand – took his bearings and worked his way upwards. He recalls Dr Hamilton treating him and that he got a lift on a wagon to his digs on the outskirts of Newport at about 11 pm that night.

He is later recorded as being annoyed that he left 5 shillings in the pocket of his coat and that it was still in the trench.

A man could be heard shouting from among the timbers, but the gap to reach him was too small for the rescuers; such men were used to physical labour and were therefore too well built.

What was needed was a small built man, and one of the crowd that had gathered fitted that need….

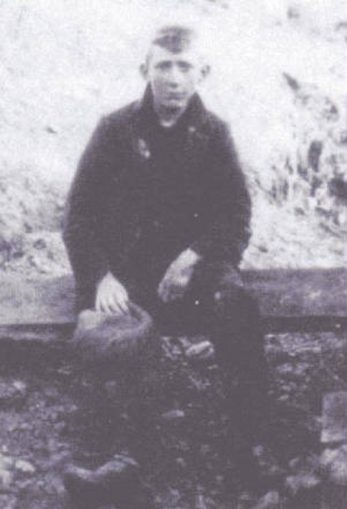

Tom Toya Lewis

A spectator in the crowd that had gathered stepped forward to volunteer; he was a 14 year old newspaper boy whose father was a stevedore on the docks.

© newportpast.com Used with permission

After some discussion it was decided to use him, so Tom was lowered down and inched his way through the maze of timbers. Finally, some 30 feet down, in the darkness lit by only a candle and surrounded by the obviously unstable earth and timbers around him, he started to saw away the beam that was trapping the man, Fred Bardill.

After around two hours working in such conditions, he had managed to free one of Fred’s limbs, when the timbers groaned and shifted and the decision was made to lift Tom out. With timbers starting to move it was all Tom could do to scramble back upwards to safety before the narrow gap collapsed.

He was bruised and bloodied so was taken to hospital for a check-up and while there, a few hours later, he received a visit.

The visitor was Fred Bardill.

Thanks to Tom’s efforts rescuers had managed to pull Fred free, and with just minor injuries he was the last man to leave the trench alive.

Rescue operations continued through the night against ever shifting timbers and earth and the rising tide that was, despite all efforts, inevitably starting to seep into the trench.

By the morning of the next day the trench was full of water and so, on Sunday 4th and with the approval of the coroner, work began to fill it in.

A total of fifteen men had been rescued alive with 5 recovered bodies.

In all 39 men were killed in the disaster; a number would have likely been crushed immediately by the falling timbers, but it is almost certain that some would have been drowned by the incoming tide.

Aftermath

The Inquest into the disaster was held locally on July 6th where the contractors issued a final name list of the missing men.

The coroner paid tribute to the quick thinking of Faris whose reaction ‘no doubt saved some lives’. Mentioned also was the ‘splendid heroic efforts made by those involved in the rescue attempt’.

Special praise was reserved for Tom Lewis for his ‘courage and resourcefulness’.

Observations were recorded that at least two workers had seen timbers shifting on the morning of the tragedy.

It was also noted that there had been unseasonably high rainfall in the days leading up to the disaster which may have affected the stability of the soil with run off affecting the seasonal height of the River Ebbw whose bed crossed the trench.

A final report placed the blame for the accident on Thomas Ratcliffe, a ganger who had had responsibility for the trench on that day. Ratcliffe himself had been injured in the collapse after being thrown in with collapsing timbers, sustaining head and chest injuries, but had then died of pneumonia before the inquest so was unable to defend himself.

His death made him the 39th and final victim.

Excavations

In December 1910, during excavation work to stink pilings for reconstruction of the west wall, 17 bodies were uncovered and exhumed; one was identified as being that of Albert King.

Recognitions

Several of the rescuers were recognised for their efforts at the disaster.

Dr Hamilton, leader of the St Johns ambulance brigade, was awarded the Arnott Medal

A number of employees from both the contractors and the Dock Company were also awarded the St. John’s Ambulance Bronze medal for conspicuous gallantry.

© newportpast.com Used with permission

And as for Tom Toya Lewis?

After being treated as a local hero by the townsfolk, in December 1909 Tom found himself at Buckingham Palace where King Edward VII accompanied by the Prince of Wales and the Duke of Connaught presented him with the Albert Medal – the civilian equivalent of the Victoria Cross.

There was also a local fund-raising effort that raised several hundred pounds to send him to Rosyth naval base, Scotland, as an engineering apprentice. The Carnegie Hero Fund contributed £50.

.. and (until 2017) there was a Wetherspoons pub* named after him!

Tom died in 1969

© newportpast.com Used with permission

*the nicer of Newport’s two ‘Spoons pubs in my opinion, but then it got closed down, so what do I know…

Memorials

On the 8th of July, a memorial service was held over the trench reportedly with some 2000 townsfolk attending. It was conducted by the Rev and Hon R.Grimston, Superintendent of the ‘Navvy Mission Church of England’.

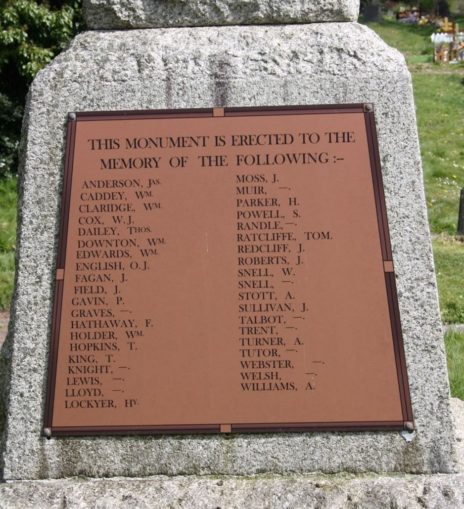

St Woolos Cemetery contains a bronze and granite memorial to those who died. It was erected by Easton Gibb and Son, the contractors on the dock extension. The names of the dead may seem sadly incomplete; this was due to many only being known by their surnames as recorded in the pay book; these were travelling men looking for work as navvies and gangers, lodging in Newport and with families back home.

Author’s note

This article was put together using different accounts of the disaster.

Due to the inevitable confusion of reporting /recording at the time, it’s somewhat difficult to ascertain the exact numbers that were killed. Officially 39 men died and that at least 16 men remain buried under the South Dock..

The irony of this tragedy is that had the collapse happened just 10 minutes later the trench would have been empty as the next shift wasn’t due to start until 6pm.

R.I.P.

… and finally

If you are thinking that the bronze plinths on the memorial look a bit plastic – it’s not my bad photography – they really are plastic. The original plinths were moved to a nearby church for safekeeping and replaced by plastic ones after an attempted metal theft in 2011 [Crikey!]

The plinths were found under a nearby hedge so it is assumed they were abandoned as being too heavy.

* * *

Video of the disaster (9m)

© Afghanistan Banana Stand 2022