I don’t know how fast you can cycle from Land’s End to Berwick. I dare say there will be a few people who have done it in two or three days, or even 24 hours. It took me 45 years.

I first began riding around England at the age of 15. Since then, I have made a lifetime goal to visit every single English town in the saddle, and put my foot on the market cross or other central feature. I’m about 95% there, I guess. I did Land’s End in 1998, and in a spider’s web of rides over the years pushed north into Northumberland. But it wasn’t until 2019 that I finally reached Berwick-Upon-Tweed.

Covid-19 has proved a good excuse to stop and look back a bit. Most of those day-rides ranged from 30-90 miles, and most were linear, with a railway station at both start and end point. There is much to say about the whole 45-year “project,” since the country I first rode around in the 1980s is now a totally different place to the one I still tour now, but that would take up a book. This is just a few articles, and they will focus on some of the places en route that stuck in the memory.

They were mostly chance finds, and mostly off the beaten track. I never ride tourist trails anyway—I pay no attention to the “attractiveness” of an area; that is not the point. For me, Leeds-Bradford-Halifax by disused rail trail is as valid and enjoyable a ride as Oxford to Bath on Cotswold lanes. The point is seeing England, every corner of it.

These write-ups will be short on history, which can be quickly looked up, and long on quirkiness. They will also have a bit of a Midlands bias, due my having spent a lot of time around the area. First out of my sack of curiosities, then, is:

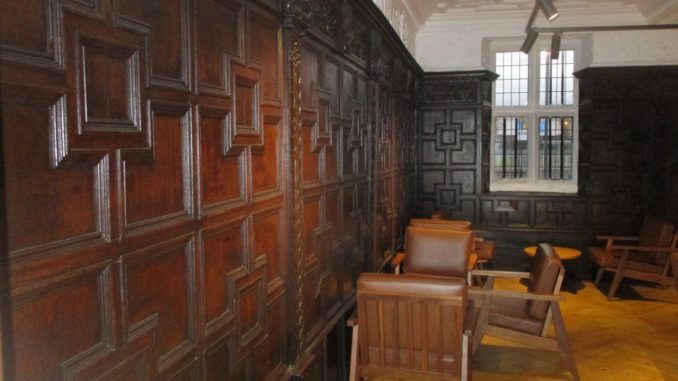

It’s not hard to find intact Jacobean interiors in England—probably every big town has one, often housing the local museum. It’s another thing to find one in use as part of a regular locals’ boozer, with Sky Sports on the screen and a pool table at the back. When I first popped into the run-down Carbrook Hall pub, which stood almost in the shadow of the enormous black Forgemasters’ steelworks in the far-from-romantic Don Valley in Sheffield, I could hardly believe my eyes. The main bar room had what appeared to be original 17th century panelling on all sides. There was a large and clearly very ancient fireplace, and the ceiling had the finest Jacobean relief plasterwork I have seen outside a stately home.

Amidst this manorial splendour, the locals knocked back their Stones, crunched their crisps and bantered about Wednesday’s chances in the Cup. In a corner was a full-size joke suit of armour in a paper party hat. Initially, that is what I took the whole scene for—an elaborate, lovingly recreated, joke. But the panelling, though which holes had been rammed at the base for electrical cabling, and the chipped stone mullions of the windows did look original. The managers confirmed it, though they knew nothing about the building except that was very old.

Well, here, very briefly, is the story. The pub building is the surviving 1620 wing of a larger mediaeval hall originally belonging to the Blunt family. It was used as a Parliamentarian base during the siege of Sheffield Castle. Centuries ago—an old map shows—it was the sole building in a large tract of unspoilt Don Valley countryside, perhaps a farm. I don’t know when it became a pub. When the steel industry grew up around it, workers would have slaked their thirst between melts with pints of Stones under those Jacobean motifs in the ceiling.

Guess what Carbrook Hall is today? A Starbucks. I revisited it soon after the conversion, and, thanks to Covid, was able to blag my way to a little solo tour inside, as the general public were not allowed in. My initial reaction on seeing the Starbucks sign on the wall outside had been “Ugh.” But the coffee chain had spent a lot of money restoring the badly run down interior. Gone were the bar, the holes, and joke suit of armour. It had tastefully and respectfully been repurposed to a coffee lounge. I changed my mind. Why not a Starbucks? I frankly can’t stand this preachy bunch of junk-food vendors, and never eat or drink at their overpriced cafes. But surely it is better that this wonderful building remain in everyday use rather than become a museum piece?

Anyway, this is the theme this week—buildings that ought to be museum pieces, but are actually still in business. We zoom now across the country to Bury St. Edmunds, Suffolk, and another 17th century house that has remained in commercial use for 400 years.

What is fascinating about the Cupola House, which stands in The Traverse in the centre of the town, is not so much the pleasing overall structure as the detail.

I was lucky enough to get an interview at this place. It has no history to speak of—it was used in the 1990s for storage by a brewery—but it must be one of the most perfectly preserved seventeenth-century town houses in England. Nearly everything is original, from overall room layout and the cupola for which it is named, down to details such as Delft tiling, lead hoppers built into walls to store rainwater, balcony railings, casements and even door hinges. The whole is grouped around a superb open-well staircase, a suspended wooden structure that looked as though it ought to have collapsed under its own weight. The survival of the interior features was due to the fastidiousness of the builder, the apothecary Thomas Macro, who had insisted on the very best materials throughout. My tour, which took a full hour, went from the cupola, added on by Macro to ensure he had the tallest building in town, down to a two-storey cellar with secret tunnels of obscure purpose, and ended with a scratch lasagne in a candlelit paneled dining room. It was one of the most atmospheric buildings I had ever set foot in, which in its various incarnations over the centuries must have been the home, haunt or workplace of thousands of Bury townspeople. Their ghosts remain, the co-manager confided: “We hear a lot of voices, calling out our names. You see human forms walking up the stairs.”

That interview happened over 20 years ago, when the Cupola House was a restaurant. Since then it has suffered a disastrous fire, in 2012. I don’t know how much original stuff I saw has survived, but online sources say it is fully restored and back in the restaurant business.

Riding one afternoon ten years ago through Shipton-under-Wychwood, in the Cotswolds, I decided to stop for a coffee at a big stone manor-house type pub with a bald monk’s head on the sign. Now, many towns have a boozer with a few “15th century” features. But when you order an Americano for the road in The Shaven Crown, you do so in what is effectively a mediaeval baronial hall, as huge and high as a church nave, with a “double-braced” roof showing a fine array of rib-like rafter work.

This is indeed a largely intact mediaeval hall with a magnificent beamed roof—a real rarity, in other words. With its jumble of ancient outbuildings, it has apparently been a hostelry for 700 years. According to its website, it was founded in the 14th century “by the monks of Bruern Abbey to house pilgrims and as a hospice for the poor and needy. Following the dissolution of the monasteries .. Queen Elizabeth I later used it as a royal hunting lodge.” The day I visited, it was hosting an exhibit of rather unattractive portraits of farm animals.

I’ll end with a few honourable mentions under the same theme, like they do on Youtube: the Jew’s House in Lincoln, perhaps the best surviving example of a residence with a largely original Norman facade, now a restaurant and beauty salon of all things; Ye Olde Trip to Jerusalem pub in Nottingham; The Old Wine House in Banbury, a Tudor ironstone shop and today still flogging plonk, and, while I think of it, a boozer in the same town with a magnificent Jacobean carved fireplace (White Hart? Horse?). Lastly, and off-theme, I would just like to mention a museum, Gainsborough Old Hall, which few actually go to because Gainsborough is so far out of the way and, to be blunt, a bit of a dump. But the Old Hall is the largest mediaeval compound I have seen anywhere that is not a castle or cathedral. Pricey, but worth the visit.

Anyway, so much for boozers. Next time, churches.

The full travelogue can be found at: https://www.itabibito.com/ (bottom left on the home page)

© text & images Joe Slater 2021

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file