Towards the end of November in this crazily craptacular COVID-19-filled year, I had a chat about fishing flies in the comments no-one reads with a fellow Postaller. More to the point, a natter about whether I had ever tied flies for sale to other people. I haven’t, currently, because I do not yet think that my level of skill is sufficient to sell anything (I’m still a newbie and have been tying for less than a year). However, I was more than happy to tie a one-off fly for my new Puffin pal. After all, it’s good practice for me and, as far as I was aware, they weren’t planning to pit my efforts against a hungry, energetic trout!

That got us into a discussion about what I could tie, a particular fly pattern they knew of or had seen and liked, perhaps one with an appropriate name, or maybe there was a certain colour (or colours) they’d like me to incorporate into a fly. I could find a suitable pattern, or let my imagination run free. Almost in passing, I mentioned an idea I’d been mulling over for a little while. I’d been contemplating trying to represent a Puffin as a fishing fly (a salmon fly rather than trout, as they tend to be a bit larger).

I’d hunted, searched and looked but, perhaps unsurprisingly, there didn’t appear to have been any flies tied along these lines, but it seemed like a fun project to try. The black and white colouration, with splashes of orange, should look quite striking, especially if mounted in a black box frame.

I asked my Puffin pal how they felt about being a guinea pig for this crazy idea and, thankfully, they agreed. Yay! There was just one small problem to overcome before I could get started and try to design what I think is the world’s first Puffin fly. On land, these lovely birds usually stand upright, showing dominance with an upright stance, fluffed chest feathers and a cocked tail, a pose which doesn’t lend itself to a hook and a fly. A problem indeed, unless that is, I could design my fly as a Puffin in flight. Before I get to the nitty gritty of how and what though, a little bit of background.

Do Puffins like muffins? Who knows, but dear to many of our hearts, these beloved and instantly recognisable small, stocky seabirds, Atlantic Puffins (Fratercula arctica), are sometimes called the ‘clowns of the sea’. Only around 32 cm (13 inches) in length and weighing a mere 380 g (13 oz), they are cheeky little chaps with their dinner-jacket black backs, crisp white bibs and tummies, those bright orange legs and webbed feet. Their rounded heads stay etched in your memory with their white cheeks, black and red eye-markings, black cap and collar and, of course, that considerable, brightly coloured, parrot-like bill!

As cute as it looks, that comical beak is something to be reckoned with—although ten to twelve fish is a more commonplace load, held in the bill with a muscular, grooved tongue, one valiant puffin was recorded holding eighty-three small sand eels in its bill at once!

Puffins’ wings are relatively small for their size, with a span of about 55 cm (just under two feet), so these seabirds expend considerable energy to take to the air. Flapping their wings around 400 beats per minute, Puffins use those bright orangey webbed feet to ‘run’ inelegantly across the water’s surface to aid take-off. To be honest, their landings aren’t very graceful either, more often than not ending in a splash as they belly-flop or somersault and roll across the surface of the water. They really are the ‘clowns of the sea’.

Once in flight though, they are pretty nippy and can reach speeds up to 88 kilometres per hour (55 miles per hour). Not bad for a little bird. Compared to other Auks (they belong to the Family: Alcidae) they tend to fly fairly high above the water, usually about 10 m (33 ft). But Puffins are also pretty expert when it comes to the water, and they are skilful divers and swimmers. They flap those semi-extended wings like paddles to ‘fly’ underwater, swimming fast and diving deep, sometimes up to 60 metres (200 feet) when they’re hunting for fish. An Atlantic Puffin’s diet comprises almost entirely fish, though they will, when in coastal waters, eat shrimp and other crustaceans, molluscs, and bristle worms.

They spend around eight months (two-thirds of the year) far away from land, bobbing around in the cold northern seas of the Atlantic Ocean. In fact, they only head for land to mate and nest, returning to their nesting grounds around mid-April each year. By the end of August, they’re heading off for another winter at sea but, while on land Puffins nest in burrows either excavating their own hole or moving into an established rabbit burrow, driving off the furry inhabitants!

They usually mate for life, raising a single chick (known as a Puffling) in a season. The pair share responsibility for feeding and rearing their offspring, but don’t always spend the winter months at sea with their Puffin partner. Instead, mating pairs reunite come the spring, when Puffins gather together in small groups offshore before returning to their cliff-top Puffin colony and nesting sites. Oddly, although they are a noisy bunch on land (when they’re in their breeding colonies they are very vocal!), they are near-silent at sea.

Did you know that it’s possible for people to have a Puffin for their Totem, their Spirit Animal? Well, this was news to me, but it seems that those with a Puffin Spirit Animal have a strong sense of community spirit. Puffins symbolise ‘storge’, familial love, one of the seven types of love described by philosophers in ancient Greece, such as Plato and Aristotle. They are the protectors, tending to come together and establish a tight-knit group. Beginning to sound familiar yet? These are intuitive folk with a spiritual sense, often extremely empathetic. They have a powerful internal compass, striving to find their own path while acting as guides those who fall by the wayside. Puffins are said to possess excellent communication skills, and they can be tenacious. One more trait—they speak their mind when they feel passionately about something. Now you may consider this to be a pile of baloney, but I’ll leave the thought with you.

Just before I regale you with the fun and games that ensued when I started to design and tie the Puffin fly, there’s another Fratercula fact I’m sure you’ll all appreciate. Did you know that there are several Puffin-related beers? No? Neither did I, but here are just a few.

The longest established brew comes from The Orkney Brewery, who named their Puffin Ale after the ‘tammie norrie’ as the bird is affectionately known in the Islands. This is a rich, spicy, fruity, sweet nutty and malty bronze beer with an ABV of 4.5 %, making it about average strength.

Next up, and from the opposite end of the UK, The Harbour Brewing Co. in Cornwall have brewed Puffin Tears IPA. Again, a beer of average strength at ABV 5 %, this is an IPA. A well-balanced brew, with a hoppy bitter finish and citrusy, stone-fruit aroma.

Finally, the new kid on the block, a dedicated Puffin-loving brewery indeed. From Penmaenmawr, in North West Wales, comes the Puffin Island Brewery. As yet, it’s too early to say what the beers will be like (they started up at the worst possible time – 2020!), but they plan to produce nano-batch, cask-conditioned real ales and ‘artisan’ craft beers. Good luck to them, I say.

There’s even a Puffin Cider, from those nice chaps at Perry’s in Somerset. With a bit of a kick at ABV 6.5 %, this is a refreshing bottle-conditioned, full-bodied naturally sparkling, dry cider.

OK, on to the fly. I started by taking a good look at lots of Puffin photos, to get an idea of proportions, colours, and shape. I have to admit that this is definitely a Puffin to have evolved considerably and designing Puffin Mark One was a challenge indeed.

For Mark One, I had decided to use the largest hook I had at that point, a Kamasan B175, Size 4 heavy trout hook. A nice sturdy hook, but only c.2.5 cm (about an inch) long. I chose white wool to wrap around the hook shank to create the body, barbs from a nice glossy black crow feather for the tail, wings and back (thank you to the kind crow who gracefully donated a nice wing feather right outside the flat!), some bright orange marabou (turkey feather, to the uninitiated) for the feet, some orange, grey-blue and black synthetic ‘wool’ for the head and beak detail, and some crystal flash and tinsel (sparkly bits) for the bill and to make the Puffin’s lunch of sand eels.

I won’t go into too much detail about this fly, except to say that tying it involved a lot of swearing! The end result was passing fair for a first attempt, but emphatically not to the standard I wanted to give to my Postaller friend. Suffice it to say this poor Puffin was too short, too fuzzy, the skinny wings were naff, and the poor little beggar had enormous feet!

However, I learned a great deal in tying this sad, misshapen fellow, with perhaps the first lesson being that I unquestionably needed a larger hook. I’d also realised that the smooth body I wanted simply wasn’t possible using my white sheep wool, which also looked a little grubby by the time I’d finished woman-handling it (despite manic hand washing). Off to my favourite online fly-tying materials suppliers, just in time for their pre-Christmas sales. Who, me? Get carried away? How could you think such a thing!

An impatient wait, with delivery delayed because of the postal service during the joys of a Covid-Christmas, and then the day dawned when I finally had all the materials I needed to make a start on Puffin Mark Two.

You can see from the photo that the new hooks with extra-long shanks, Maruto i09, Size 2, are considerably longer than the original, at nearly 5 cm long (close to two inches). I had plenty of sparkly stuff (visits to charity shops yield all sorts of little treasures) but I’d ordered some decent Hot Orange marabou for the feet (making a mental note to remember about proportions), a suitable white thread, some lovely, black-dyed goose quill for the tail and wings, and I’d stocked up on the Antron body-wool.

Just a little aside, I did a bit of reading around and found out a bit more about Antron, which I had only encountered recently. It really is an incredibly versatile synthetic material for tying. It has a unique texture, size and shine, and that means Antron can be dubbed, smoothed, twisted, and teased, making it suitable for bodies, wings, tails, shucks (the case which insects that are transitioning from a larva to an adult break out from), and much more. Simply put, Antron is a synthetic (trilobal nylon) rug yarn developed by DuPont for use in carpets. Millions of miles of it have been manufactured in a welter of colours, and fly-tying folk may know it as Antron Body Wool, or by various other names, like Z-Lon, Permatron, Darlon, Aunt Lydia’s sparkle yarn, and variations.

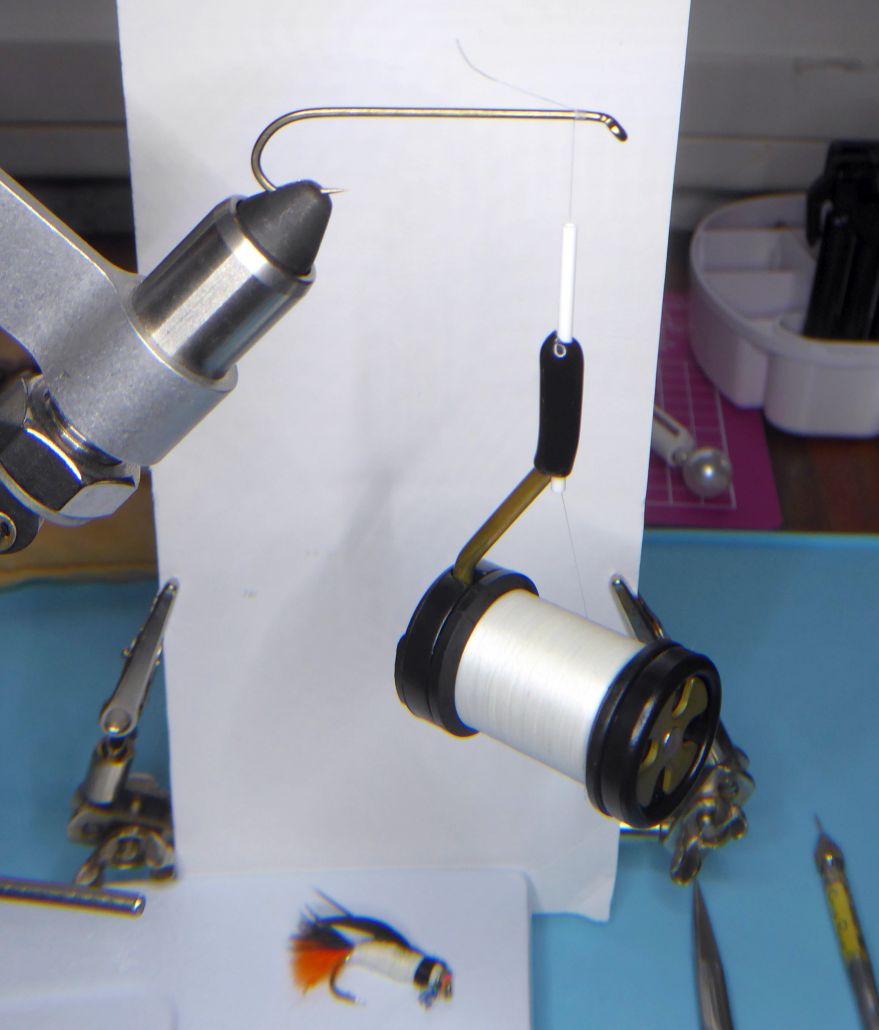

So much for the materials, but what tools do you need to tie? For those of you who are not familiar with the paraphernalia involved in this all-consuming pastime, the next photo shows you the basics.

My biggest, most expensive piece of kit is a decent, heavy-based vice to hold the hook. This one is a substantial piece of American engineering, a Peak PRV-G2 vice from Loveland, Colorado. It was bought as a treat when I started tying seriously. Made of stainless steel, tool steel, aircraft aluminium and high-quality brass, it has a rotary head so that you can easily view the fly from all angles, and it’s built to last a lifetime. A luxury as, in reality, a cheap and cheerful, beginners fixed vice can be bought for not much more than £20 (a couple of these can be seen in the next photo).

To the left of the vice is a W. Heath Robinson affair to collect stray off-cuts of stuff as I tie—a sticky sheet of Wilko’s finest lint roller refill, bulldog clipped to a plastic lid from something or another. The adjacent Christmas tree is, sadly, non-essential.

The other worthwhile spends were a good quality pair of scissors with sharp points, and a sturdy bobbin holder. I chose Veniard fly-tying scissors (with the black handles) but also have a pair of Pfeilring curved-tip cuticle scissors which have proven invaluable. The bobbin holding my thread reel is a Rite Shorty (specifically chosen as I have little hands). A range of other tools are repurposed from my old dissection kit, and I have made a couple of things, like the whip-finishing tool, where I decided I was too mean to pay the elevated prices some of these simple bits and bobs command. Once a laboratory technician, always a technician!

An overall view of my tying bench (a posh term for a small fold-up table stood on a box) shows my notebook, a piece of white card held in a ‘third hand’ stand to give me a plain background against which to see the fly properly while tying, and an adjustable magnifying lamp, now much needed as my eyesight is apparently not as good as it once was!

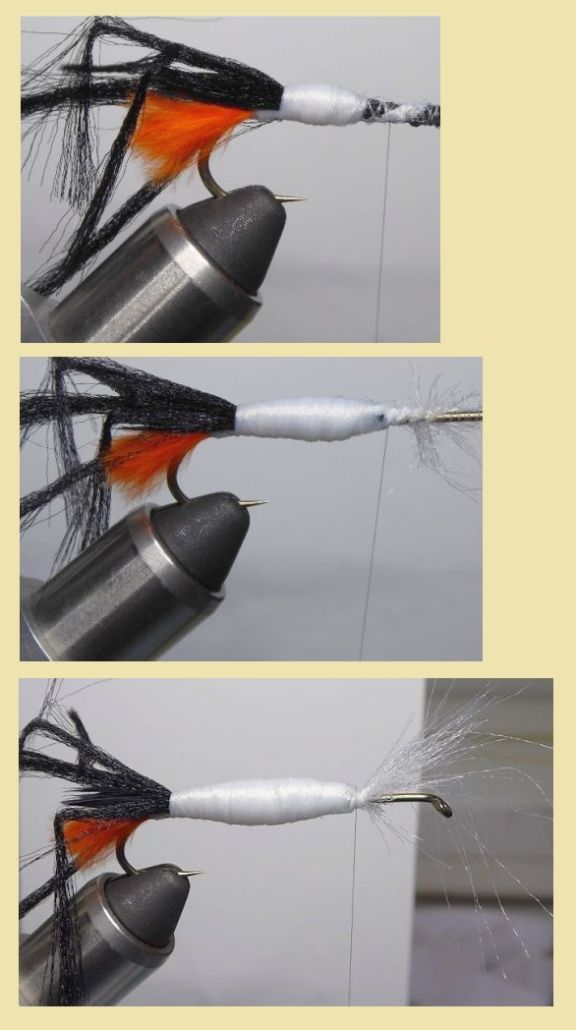

So that the tying can commence, it’s time to properly seat my hook in the jaws of the vice to hold it stable and steady. Once in place, I can test it by flicking down on the hook’s eye with my thumbnail. If I hear a satisfying ‘ping’ and the hook stays put, I’m good to go. To ensure my tying thread is securely attached to the hook, I wind the thread from bobbin around the shank of the hook, clockwise, three or four turns towards the eye, then a few turns back towards the curve of the hook trapping the initial turns underneath. At this point, if I let go of the bobbin, it should just dangle without everything unravelling. I can then wrap the thread along to hook towards the bend to give a nice base and start adding the materials I want to build up my fly.

Typically, for almost every fly pattern, you would start adding material near the bend of the hook and work forwards towards the eye. Even though I didn’t have a pattern for this, as I’m designing it as I go, the principle still holds.

That means my first job is to make the Puffin’s feet, so I tie in a bunch of fibres from the orange marabou feathers. It doesn’t matter that the feathers are way too long at this stage as I can pinch them to the required length once they are tied down onto the hook nice and securely.

Pinching the ends off between my thumbnail and fingertip, rather than using scissors to cut the feathers, gives a nice natural appearance.

With the feet in place, I can now tie in some white Antron body-wool over the butt-ends of the marabou, then add a few short barbs of the black goose quill, fanning these out as I tie them on to form a decent-shaped tail. The white Antron will be wrapped around the middle of these feather barbs, helping to keep them aligned and in place.

But, before I start to wrap the white Antron and begin to build up the body of my Puffin fly, I need to secure some black Antron body-wool onto the hook. Three separate sections will be needed, each of which needs to be left long enough to be laid over the body along the length of the hook, to be tied down just behind what will become the head. One section is tied in right on top of the hook (this will be bent over forwards towards the eye to form the back of the Puffin). The other two sections are tied in, with one at each side. The side sections will lie along the side of the Puffin’s body under the wings, to form the flanks. With floppy strands of black Antron sticking out at crazy angles, it may look like an explosion in spider-world at the moment, but it will all come together.

The next stage is where the shape of the Puffin’s body starts to build up, with layer upon layer of white Antron body-wool wound on to the hook. The shape is important, and the turns carefully placed to give a tapered Figurado Perfecto cigar shape. As you will see from the photos, a good gap of bare hook shank is left between the end of the body and the eye of the hook. This is where the head and that all-important colourful Puffin beak will sit, so space needs to be kept for these.

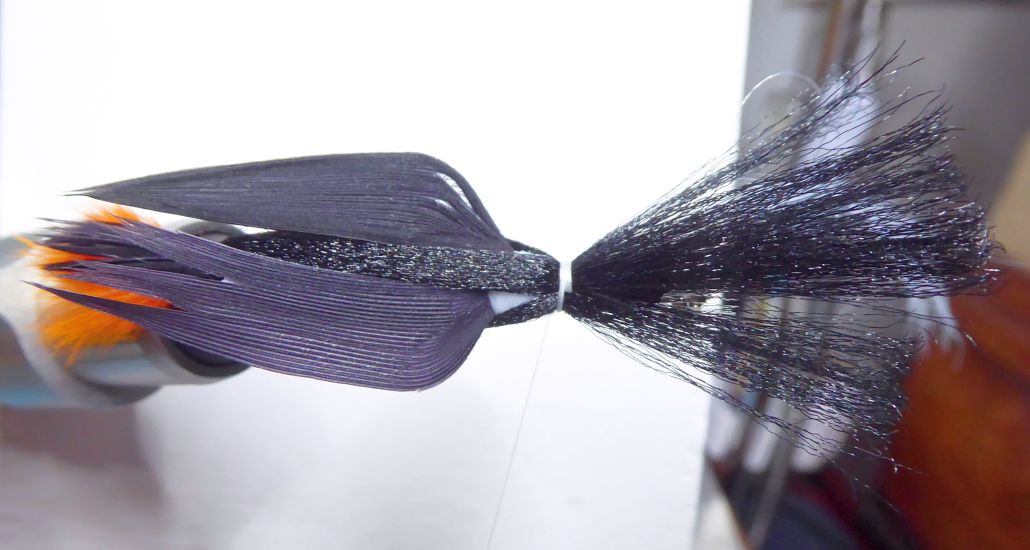

Before we get that far though, there are wings to think about, and this caused considerable cogitation. In flight, a Puffin’s wings could be up, they could be down, they could be out at full stretch, pointing forward, pointing back. What would look best, and how could I tie them onto the hook and keep them in that position? Back to the photographs I went, keeping in mind that the wings I’d made for Puffin Mark One were too skinny and I’d need to use a broader strip of feather barbs to make my wings this time.

Having changed my mind only a dozen or so times, I decided that tying the wings roughly level with the body might look the most attractive, similar to the photo below, but with the wings angled slightly backwards towards the tail. That would allow me to tie them onto the hook with a figure of eight arrangement and, hopefully, they’d stay just where I wanted them to.

To prepare the wings, I stroked a fairly broad section of the longest barbs of goose quill straight out from the feather’s stem, until they lay approximately at a right angle to the stem. This gave a nice, graceful curve to the fibres and a natural-looking ‘fingertip’ end to the wing. I used matched feathers, one from each wing of the goose, to achieve a corresponding shape for each of my Puffin’s wings.

A thin coat of the wonderfully named ‘Floo Gloo’ Tying Cement, a clear, flexible liquid from Veniard was called for to hold the feather fibres together. This, in effect, ‘welds’ them in place in the desired shape, before securing them to the hook, on top of the Antron body I’d just built up. I hadn’t used this before, but all went well, and a light coating of the glue was applied to the first feather, which was set to one side for the Floo Gloo to dry.

Cocky now, I had started to apply the liquid to the second feather when disaster struck. I was carefully holding my camera in one hand to take some photos (similar to the one below, but ‘in action’ where the bottle was uncapped). I had the liquid-covered paintbrush in the other hand applying to glue to the feather. My attention divided, I took a couple of shots then, luckily, put the camera down out of the way.

As I turned my attention back to my paintbrush and feather, I screwed it up. I promptly knocked the whole bottle of Floo Gloo all over the table and the base of my vice! I grabbed the bottle and the feather to save what I could, but by now the liquid was oozing towards the edge of the table. All I could do was ensure that when it dripped, it was into my lap, so it didn’t go all over the carpet.

It soaks into jeans rather well, and the damn stuff is waterproof. Did I have a bottle of the special ‘Unitit’ (I kid you not) thinners to hand, to clean it up? Of course not. Oh well, it wiped off the vice and the silicone sheet I use to cover the table, but that’s a pair of trousers that’ll never see the outside world again. You can’t say tying is boring!

Once the swearing had subsided, and I’d peeled the Floo Gloo ‘welded’ jeans off my thighs (er, filth indeed – I’m just grateful I’m female so they’re not hairy!), my feathers had dried, so the barbs could be trimmed away from their stems. Slightly folded and gently bent, I could then use strands of the white Antron in a figure of eight to secure the wings to the body. They ended up lying backwards at a sharper angle than I’d planned, but I wasn’t entirely unhappy with the look of the wings that way.

It’s at this stage that those dangling strands of black Antron body-wool come into play. The top section is brought forwards from the tail, along the back and between the wings where they meet the body. Drawn smooth and held taut, it is secured with several turns of the tying thread at the point where the body will meet the head.

The next bit is where a rotary vice comes into its own, as the whole fly can be rotated in the jaws of the vice so that the side sections of black Antron can be seen. One at a time, they can be drawn along the sides of the body under the wings, again to be secured where then body and head meet. These form the Puffin’s black flanks.

With the back and flanks in place, a collar of black Antron can be tied in over the point where the back and flanks are secured. This hides the white tying thread and allows me to leave a long strand which will become the black cap over the Puffin’s white head. At this point, the eagle-eyed among you may spot that there is a small gap between the back and the flanks, just in front of the wings, where the black Antron doesn’t cover, and the white body shows through.

Never fear, Sharpie is here!

No, not me. This is Sharpie the Permanent Marker, in black, preferably with a fine point. Another benefit of using the synthetic Antron is that it easily takes permanent water-proof markers and can be coloured almost any shade by gently drawing the tip of the pen across the fibres. The ink is alcohol-based so will not wash out when the fly is used. You do have to be apply it with a delicate touch though, as the ink can easily travel along the fibres.

We now get to the trickiest stage, which of course coincides with when I’ve been tying for some time and am getting tired. This is the Puffin’s head and beak. Not a lot of room, lots of different materials to insert in the right sequence, and several small details to take care over and make noticeable. If it’s going to go wrong, this is where it’s likely to.

Building up the shape of the head is straightforward, just wrapping layers of white Antron body wool to create the desired rounded shape. Notice that long strand of black Antron, which will become the cap.

Adding the details of the head and beak is the most fiddly and time-consuming part, and I’ll confess I didn’t have the patience to try to photograph it as well. The sequence of events though was to bring the black cap over the head once the desired shape had been made. Then a circlet of fine round golden tinsel is used to delineate the start of the beak, followed by a few wraps of blue-grey Antron, and a second golden tinsel circlet.

This is when the Puffin’s fishy lunch can be added. A few short strands of crystal flash, in several colours (blue, black & silver, and iridescent), are cut, and tied beneath the Puffin’s bill. The ends can be trimmed to the desired length once the bill is completely finished—the final stage, which takes place with a couple of turns of bright orange Antron, sloping down to a point towards the eye of the hook.

This is secured with the tying thread, a couple of half-hitches and a whip-finish will suffice, and the thread, together with any loose ends of Antron, can be cut away. All that’s left to do now is give the tip of the bill a light coat of varnish to ensure all fibres are held securely in place, and the Puffin is complete!

This photo actually shows Puffin Mark Three. “But why was there need for a Mark Three?”, you might ask. Well, my perfectionist tendencies kicked in when I looked at the completed Mark Two, then at pictures of real Puffins, then back at Mark Two.

I’ve mentioned that there’d been a process of evolution, and I have already detailed several of the faults I’d identified for poor Mark One. Mark Two was a definite improvement, but comparing him with the birds themselves, it struck me that he was rather too slim in the body for a proper Puffin. I’d go as far as to say he was verging on the anorexic!

Now I really started to pick fault. His head wasn’t distinctly rounded in the way I’d wish to see, the orange section of his bill was too bulky and didn’t taper towards the eye of the hook. Though I’d been moderately happy with the wings whilst I was tying Mark Two, the lay of them now just didn’t look sufficiently accurate. Not only that, but they also stuck out to the sides quite a way—they’d be a challenge to squeeze into a box frame. And those feet… again, even for the ‘clown of the sea’, they were a tad oversized. So, on to Mark Three it was, and I started tying again.

Learning once again from the mistakes made with Marks One and Two, the tying was more streamlined and straightforward. Even Mr Sharpie noted that he hadn’t heard many expletives, and before long it was possible to compare the three finished Puffins.

At long last, a Puffin I’d be happy to frame for my Postaller friend, but I think the framing will have to be a tale for another day. All this began with a question about tying flies for sale, and I still say that that isn’t an option.

But, if I ever do change my mind, I think I’ve found the coinage I’d like to be paid in!

© SharpieType301 2021

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file

Audio Player