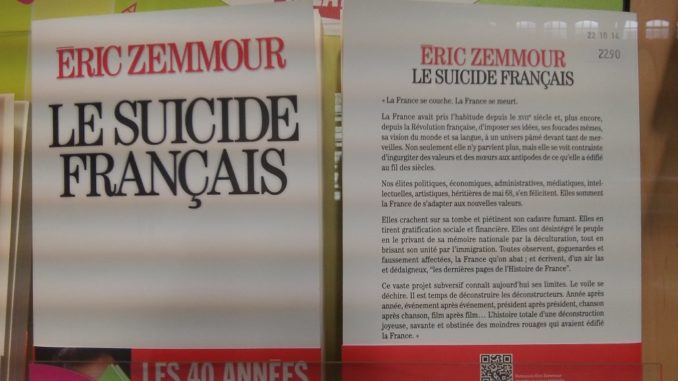

Note: This text is not a translation, but is largely based on Le Suicide Français by Éric Zemmour (2014), from which it quotes heavily, both directly and silently. The analysis is Zemmour’s, not mine, and is presented here mainly because his superb study is unavailable in English.

On la trouvait plutôt jolie,

Elle arrivait des Somalies

Dans un bateau plein d’émigrés

Qui venaient tous de leur plein gré

Vider les poubelles à ParisLily People found her rather pretty, Lily

Lily She came from Somalia, did Lily

In a migrant boat over the sea

They all came willingly

To empty the dustbins of Pa-ree

From the early 1970s, France has had no consistent policy on immigration, and has taken a zigzagging, stop-go approach that is hard to analyse.

Mass immigration in the modern sense began when Pompidou brought millions of foreign workers into French factories. The oil crisis temporarily staunched this flow. But then, for humanitarian reasons, the government decided to allow “family reunion” — chain migration — across the Mediterranean, and the influx resumed, providing a stop-gap solution to labour shortages. The newcomers came in the teeth of opposition from the people, and also, paradoxically, at a time of gradual de-industrialisation. Women and children had come in numbers that had not been expected, so that social services were overburdened and construction of high-rise tenements could not keep up. Bidonvilles had mushroomed, schools were submerged, classes collapsed and neighbours fulminated. France’s humanitarian gesture had turned into an administrative disaster. The brakes came back on and 500,000 foreign workers and their family members were “encouraged” to return to their home countries.

Prime Minister Raymond Barre (1976-1981) did not share the “romanticism of the desert” of his predecessor, Jacques Chirac, writes Zemmour. Barre actually saw immigration — I know this is hard to believe today — as an obstacle to systemic modernisation. In this, moreover, he was in tune with the nation. By 1977, more than half of France’s citizens said they wanted to see immigration curbed. And in those benighted days, the views of the electorate on immigration were actually taken seriously. Already in 1976, family reunion had been suspended, to “protect the labour market,” but the Council of State had declared the move illegal. Barre lost this battle eventually in the National Assembly, but he did not give up. In 1978, in a move that could have been borrowed from Enoch Powell, he set up the “aid for return” programme, which included handing a cheque for 10,000 francs to all foreign workers willing to repatriate with their families. The bribe backfired. Those who pocketed the cash were the Spanish and Portuguese, while the Maghreb Arabs, the ones the French actually wanted to leave, stayed put. The programme was revived in 1982, with the pay-off boosted to 100,000 francs, but it still did not work.

By this time, the immigrants themselves and their French supporters were beginning to organise. The following year, the Marche des Beurs campaign forced Mitterrand, who after his inauguration had already promised to regularise 130,000 illegals, to introduce a ten-year residency card. In the same year, the Front National installed itself in the political landscape. They had achieved mass appeal by the mid-1980s, when I was there. Also founded at this time was SOS Racisme, France’s most vocal pro-migrant organisation.

The battle lines drawn up, the immigration controversy took on aspects of a culture war. In the early days, migrant workers often astonished the French with their sobriety, discretion and “moral elegance.” Mostly Algerian Berbers (from whom French-born Zemmour is himself descended), “they were secretly delighted to find a lay society where the rules of the Koran were not applied under the strict and rigid control of their neighbours.” The film Dupont Lajoie (The Common Man), which made hay out of racism at a campsite near a migrant quarter, typified the liberal tendency to glorify North Africans and vilify Français de souche (native French) as bigoted clods. A number of well-known singers joined the adulatory chorus:

Ton étoile jaune c’est ta peau

Ne la porte pas comme on porte un fardeau

Ta force est ton droit

Si tu crois que ta vie est là

ll n’y a pas de loi contre çaYour yellow star, it is your skin,

Don’t bear it like a heavy thing,

Your might is your right

If you think that your life is there

There’s no law against you to cite

Thus the idealism. The reality was that, since 1948, half of the 100,000 acts of aggression in Paris each year were caused by Maghreb people.

But in the 1970s, “the hatred of France redoubled into a detestation of the French, especially the lowliest of them,” writes Zemmour. The internationalism of the left having broken with the patriotism of the French Revolution after the war of 1914, the working class came to be imagined as “a mass of rednecks, alcoholic, racist and macho .” The stereotype was further sullied by the inglorious memories of the war. A young generation which did not know occupation condemned the behaviour of its fathers, who were simultaneously guilty of losing the war, collaborating with the Germans and betraying the Jews. The leftist leaders were often Jewish, sons of the Ashkenazy, who had been expelled or delivered to the Germans because they were not of French nationality.

At the same time, “the face of immigration and of France changed. Worker immigration of flux connected to economic activity, which one day returns to the [home] country, was succeeded by settlement immigration of families. .. But still, the men sought their women in the little home of their parents, so as to avoid breaking the ancestral chain of cousin marriage – and so as to secure a young girl less contrary than the young Franco-Arabs “perverted” by liberal French ideologies. And a growing number of (second-generation) immigrants begin to resent feeling “humiliated” by the French as their fathers were, on the production lines of Renault or Peugeot.”

The reference in the song above to the “yellow star” was not gratuitous. Vichy loomed large over the entire postwar immigration debate and provided the high-octane fuel of indignation that drove the left. Almost alone among occupied countries, the French succeeded in saving most – three-quarters – of their Jews from the Nazi concentration camps. (By contrast, almost three-quarters of the Netherlands’ Jewish population were deported.) The difference was that the Vichy regime decided, under German pressure, to sacrifice foreign Jews living on its soil or taking refuge there, to save the French Jews. This policy has had far-reaching repercussions. In the postwar age, it has made the French reluctant to firmly police their borders, insist on assimilation, deport foreign criminals, expel sans papiers (“undocumenteds”) or indeed do anything that the evoked the Vichy betrayal in the faintest way. In a brilliant passage, Zemmour explains how the shameful memory has inspired the pro-immigrant lobby:

“For all of the pretty actresses who posed at their sides, for the Papiers pour tous (Papers for All) committee members who blocked a paddy wagon from leaving the courthouse, for all the judges who tracked the procedural errors of the police, for all the aircraft captains who refused to take the sans-papiers sent home in their plane, for all the activists who found them subsidised accommodation and fed them and gave them legal advice on not being expelled, for all the labour inspectors who haughtily refused to check for clandestine workers, for all the students who protested against the expulsion of their “comrades” schooled with them, the sans-papiers showed themselves to be a godsend, an ideal Jew for whom they could deck themselves in the robes of righteousness without risking the bullets of the SS … For all French who had not been able to, or known how to, or wanted or dared or desired to save the Jews in 1942, history, that faithful handmaid, had provided a second chance. .. The sans-papiers was not just the ideal Jew. He was also the return of the poor persecuted stranger, a Christian figure, come to save French society in spite of itself, which, decadent and corrupt, had sinned much. .. He sounded the return of the noble savage of Rousseau.”

Again, the reality was more squalid. “The two pillars of the underground economy are .. the sans papiers and drug-trafficking. Having come illegally into French territory, the sans-papiers were forced to reimburse criminal networks who brought them to France as fast as they could. When they did not find enough work in construction or a restaurant, drug-trafficking stretched out its arms. Over the years, the mechanisms and connections perpetuated and reinforced themselves. The same ferrymen, the same families, the same ethnicities, the same regions. Here and over there.”

Elle rêvait de fraternité,

Un hôtelier rue Secrétan

Lui a précisé en arrivant

Qu’on ne recevait que des BlancsLily She dreamed of fraternité, did Lily

A hotelier in the Rue Secretan

Told her en arrivant

That they only accepted Blancs

Pierre Perret sang his jauntily bitter song about Lily from Somalia in 1977, at a time when immigration was changing its nature, Zemmour writes. They were now no longer coming to Paris to empty dustbins but to rejoin a father, brother or mother. Having brought immigrants over instead of investing in modern machinery, as their Japanese counterparts had done, French bosses brought about the destruction of the working class through family reunion.

“The thinking was simple, even simplistic: these populations were no different from the peasants that came in from the cities in the 19th century. They had to be assimilated, taught how to use a toothbrush, a pen, a washing machine … and not to slaughter a sheep in the bathroom.” Family reunion became the “great posthumous revenge of the partisans of French Algeria over General De Gaulle.” In his analysis, Zemmour notes how the slow disintegration of the French family in favour of individualism was “compensated for” by inviting the traditional Maghreb family, the most archaic and most patriarchal of all, to replace it.

“France never quite understood that a strong sense of cultural and ethnic identity is not the enemy of democratic values, but rather its necessary and natural complement. It forgot that the French Revolution, its gift to the democratic world, was not created in an ethnic and cultural vacuum, but by people with an identity and history – a white European identity. In a way, history has come full circle: what France originally exported as an idea, the radically culture-blind republic, leaves her now helpless in the face of its own rapid de-Europeanization.”

Bien-pensant French have also rejected their past. “Napoleon is hated because he incarnates to the point of caricature what our country once was. In the scholarly histories, for college or grammar-school students, his innumerable battles are not even mentioned. All that is sometimes kept in is his defeats: Leipzig because it forged the German nation, and Waterloo because it founded British hegemony. All the people want to remember about Napoleon is the Civil Code, the prefects, the Bank of France. .. They think French eulogising of the emperor is seen as a relic of the arrogance of the Gallic cock, which they consider at best ridiculous and at worst detestable. They think that Europe can only be built on the denial of the greatness of France.”

© text & images Joe Slater 2020

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file

buy viagra online займ на карту мир срочноонлайн займ на чужую картузайм на карту вэббанкир займер взять займвзять займ онлайн срочно на карту без отказазайм на карту без отказа с плохой кредитной историей