Hong Kong in November feels and looks very different than it did in May. The weather is glorious – the wind has changed, the humidity decreased and a very comfortable 25 degrees. But of course

The first thing to notice is that there less people about. Hotels and flights are about a third empty and the number of visitors, particularly those who come for sightseeing and shopping, is less. And this makes Hong Kong sound different as well: local Cantonese is heard much more than the usual Mandarin of mainlanders in the tourist honey pots of Tsim Sha Tsui waterfront and the New World shopping plaza at Sha Tin. Friends tell me there is less traffic on the roads – one is enjoying using a motor bike more because its less frenetic. Oh, and the police are too busy to bother with parking tickets.

Instead, the police are in full control mode. Despite the existence of undercover operators from the mainland almost all Hong Kong police are locals and don’t seem to like either the protests or their role in containing them. 23 weeks of sometimes serious confrontations have so far produced many arrests but isolated serious injuries – a student shot by the police from very close range, and this week the stabbing of a politician and the so far unexplained fall of a student from a car park while being pursued by police. The student suffered brain injuries and has died. Other countries might have had rather more casualties by now and there is often more restraint than one might expect.

Local feeling towards the police is less kind. Graffiti and fly-posting – previously rare in Hong Kong’s public spaces – is now widespread and much is anti police. Slogans include ‘Hong Kong police know the law but break it’ (香港警察 知法犯法) and ‘dirty cops’. There is plenty of evidence of police using truncheons on crowds gathered and distributed almost instantly by social media.

Social media is the most striking aspect of the protests. Most protesters are young, in their early twenties. They know that in 2047 Hong Kong will lose whatever rights and status are left by then and will become full China. So they see their own children, by then of course in their own early twenties, with no independent legal system (less than 3% of those who come before the criminal courts in mainland China are cleared), no democracy, no free speech, no land rights, no WhatsApp, no Google, no free press. WhatsApp is widely used in Hong Kong but is blocked in mainland China because it is double encrypted, so can’t be intercepted. Instead, mainland Chinese are allowed to use the single encrypted WeChat. During the protests, WhatsApp has allowed protesters to move round Hong Kong on short notice using the brilliant public transport system. This has made things difficult for the police. As well as protests at LegCo (Hong Kong’s assembly) protests have sprung up at the tourist centres of Sha Tin and Tsim Sha Tsui, perhaps to sow a few seeds in the minds of mainland visitors. And of course, there was the airport occupation which gathered international attention.

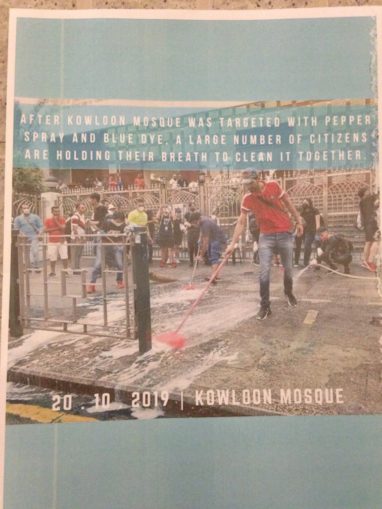

The protesters tactics are nimble and creative. After the police started to use tear gas grenades (shamefully supplied by the UK) protesters turned up with squash rackets and hit them back. Security cameras were removed by power grinders. A ban on masks prompted the (legal) use of face paint. And of course the ultimate symbol of the movement, the umbrella, is used to protect against sun, and rain, and the same tear gas. This young way of thinking has confused the old establishment, which has responded by closing down stations and MTR train routes for a few days and now finishing services early at 11 pm instead of 1 am. The fly-posting and graffiti accuse the police of exceeding their authority by doing this. Carrie Lam, Hong Kong’s Chief Executive, is largely invisible locally, delivering her annual review to LegCo by video link and abandoning press conferences. She is more visible on the mainland, appearing yesterday for a photo call with President Xi Jin Ping. This strongly suggests that Beijing is not going to be seen to make any concessions to the protesters. The nominal cause of the protests – an extradition bill – has been withdrawn but the protests were always about more than that. This has been simmering since 2014, after Beijing broke a treaty commitment to allow a free vote for Hongkongers for their Chief Executive. Yes, a free vote would be allowed: but only approved candidates could stand for the post. Now, the protesters big slogans have become ‘Five demands, not one less’ (五大訴求 缺一不可) and ‘Liberate Hong Kong; revolution of our times.’

Many in Hong Kong are sympathetic to the protesters cause but actively dislike some of the hard line tactics being used on both sides. Perhaps forthcoming local elections, on November 24th, might be seen as different way of focusing efforts? Well, they might be, if people were allowed to stand. Joshua Wong, probably the best known face of the protesters, has been banned from standing because he pledged “insufficient allegiance to the HKSAR’. Some local commentators have said this is counter productive. Mike Chinoy, in the (pretty much) independent South China Morning Post, suggested that ‘By blocking Joshua Wong from standing for election, Hong Kong is just driving protesters back to the streets’. Press coverage generally here is considerable and the protests are covered throughout Asia, with one exception. In mainland China there is no coverage at all.

Going into the famous Foreign Correspondents Club a night or two ago I noticed a collection box at reception. It asked for donations to help an Indonesian journalist, Veby Mega Indah, who was shot in the eye some weeks ago. Funny what gets reported and what doesn’t.

© Hongkonger 2019

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file

Audio Player