In the current extremely uncertain days, I don’t know about you, but my thoughts have been regularly wandering off into ‘what if’ territory. I’ve been pondering what ‘might’ happen, what is important to me, and how we might survive if an already crazy world gets crazier still.

Not unusually, my thoughts have pursued that expression much loved by The Institute of Advanced Motorists observers in their programme based, at least in part, on the Roadcraft manual and ‘the system’ used to train police drivers: ‘hope for the best and plan for the worst’ [I’m whispering about the IAM as Mr Sharpie followed what he assures me is the rather more rigorous ROSPA route!]

Mind you, neither the IAM nor ROSPA coined the expression. Plod didn’t either as it, apparently, dates back to 1561 when it was first used in Thomas Norton and Thomas Sackville’s ‘The Tragedie of Gorbuduc’, a play performed for Queen Elizabeth I in 1562. Earlier still, sometime around 46 BC, the Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar and sceptic, Marcus Tullius Cicero wrote ‘you must hope for the best’ in correspondence with a friend, so I guess people have been planning for the worst for a very long time.

On that basis, one of the things I’ve been doing is, as I know many Puffins have, stocking up a little. Not massively, as we don’t have much space, but sufficient dried and tinned foodstuffs to keep us going for a while if getting out for one reason or another (lockdown, civil unrest, or worse) becomes difficult or impossible. This makes for fairly unusual bedroom decoration but needs must.

The flat we live in is all-electric, as housing associations won’t trust us old gits with that nasty, dangerous gas stuff. If things get really bad and the power goes off then, Houston, we have a problem! Likewise, the water supply, and it’s this concern that begins to bring me around to the subject of this article. Well, nearly – yes, I know I digress.

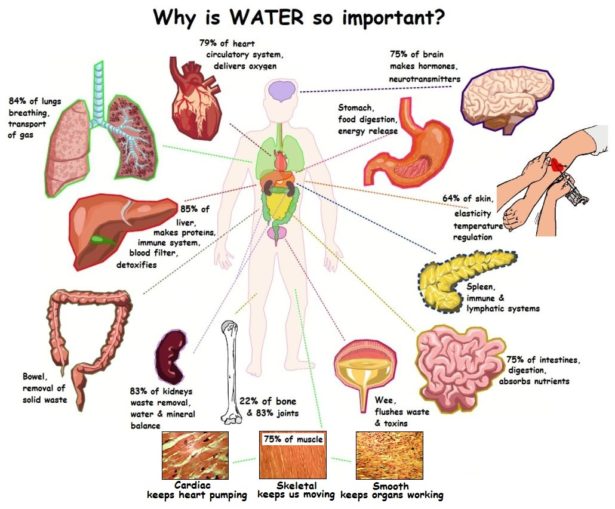

What to do should the water be cut off has given me some pause for thought. Clean, safe drinking water is the number one priority—in fact, it’s critical for survival. We humans need a minimum of a couple of pints of this precious liquid per day just to stay alive. It helps regulate body temperature, aids the digestion process and the resulting waste disposal, and so much more.

But water takes up a lot of space, and our flat doesn’t have much storage room. Regrettably, those wily, imaginative scientists have spent so much time making charts to illustrate their Covid predictions they’ve simply not given sufficient consideration to the notion of dehydrated H2O!

The water dilemma has kept me awake into the early hours, but it’s also meant I’ve taken a cursory look at a few of the Prepper sites, just in case there’s something we could do. Whilst I was Googling away (OK, it was actually Duck Duck Going) I stumbled across something I’d never heard of—something which intrigued me. Like a latter-day Alice in Wonderland (albeit somewhat older and stouter), I delightedly disappeared down the internet rabbit-hole to find out more about this serendipitous discovery. It’s certainly related to liquid sustenance, but despite the title, it isn’t tea. So, let’s put aside today’s doom and gloom for a while, and think about a substance dear to many a Puffin’s heart.

Now this topic may well be one that some of you will know a lot more about than do I. If that’s you, I’d be fascinated to not read your comments. It concerns a 1950s ‘Cold War’ project, assigned the name ‘Operation Teapot’, which was planned and conducted jointly by American scientists and military advisors.

The United States deployment of atomic bombs at Hiroshima and Nagasaki during World War II had permanently altered the global outlook for the future. Fear of atomic warfare penetrated deeply into the consciousness of people around the world as, although technically at peace, tensions intensified between the superpowers, the United States and the Soviet Union together with their respective allies.

George Orwell, in an essay written in 1945, shortly after the first use of atomic weapons, considered what the atom bomb might mean for international relations. He described the superpowers (the ‘new empires’) as being in “a state which was at once unconquerable and in a permanent state of ‘cold war’ with its neighbours”. The term ‘cold’ was chosen because, thankfully, no direct conflict took place between the two superpowers. However, both backed smaller but significant regional conflicts—proxy wars—and the Cold War was also pursued through propaganda, political and economic means.

A doctrine of mutually assured destruction (MAD), based on the theory of deterrence, discouraged a preemptive nuclear attack by either side, but relied on both parties maintaining nuclear parity (or at least preserving the means to make use of their second-strike capacity). With reciprocated distrust, MAD provoked an ongoing arms race for superiority. Operation Teapot, driven by increasing American concerns over the nuclear arms race, was an integral part of this, being designed to test new kinds of fission devices.

In total, Operation Teapot comprised fourteen nuclear test explosions, carried out between February and May of 1955. A broad variety of fission devices were tested, with low to moderate energy yields ranging in tonnes from 1 kiloton (kt) to 43kt. Delivery methods varied, including tower detonation, parachute drop, free air drop and underground shaft/tunnel detonation. The operation’s primary aims were to determine military tactics for ground forces, should nuclear war ensue, and to improve their understanding of delivery strategies in order to fully grasp the fine-details of the effects of nuclear weapons and, of course, lead to the development of more efficient methods of destruction.

However, should those big red buttons be pressed, surviving a nuclear strike not just during the initial blast but in the days afterwards was a matter of serious concern. Consequently, one facet of Operation Teapot, known as Project 32 (or Programme 32), aimed to ascertain the ‘civil effects’ of an atomic explosion on commercial food items, including bottled and canned goods, one of which was… beer.

Tests were conducted to answer pragmatic questions about what would be realistic and prudent for American people to eat and drink if the bomb was dropped. The scientists and military advisors were nothing if not thorough and included over 100 different foodstuffs, based on the foods most frequently used in the American diet, broken down into five sub-categories.

| Project 32.1 | Bulk and retail items | Sugar, flour, margarine, butter, peanuts, and lard |

| Project 32.2 | Heat processed foods in cans and glass jars | Fruit, vegetables, juice, soup, baby food, evaporated milk, meat, poultry and seafood |

| Project 32.3 | Processed and fresh meats | Ham, bacon, bologna, frankfurters, and five types of fresh meats (refrigerated) |

| Project 32.4 | Semi-perishable foods | Fresh and dried fruit and vegetables, breakfast cereals, and candies (stored in a variety of different packaging materials) |

| Project 32.5 | Frozen foods |

Various (kept frozen using dry ice) |

Serious preparation indeed, but at the eleventh hour, the scientists realised that although they had focused on foodstuffs, they hadn’t given as much thought to the problems of keeping hydrated.

They realised that, in the event of nuclear attack, American water supplies would immediately become contaminated by radioactive fallout and could remain non-potable long after those mushroom clouds waned. As we’ve already seen, water is an absolute must for survival. Indeed, the AEC (Atomic Energy Commission) at Oak Ridge published a report stating that “The needs of human water, especially under disaster conditions, could be immediate and urgent” so they, like me, started wondering whether they could come up with a Plan B.

Bear in mind that, unlike today, bottled water wasn’t readily available in the mid-1950s, and yuppies were a bit thin on the ground. Most people got their water straight from the tap, so the scientists looked at alternative sources of fluids.

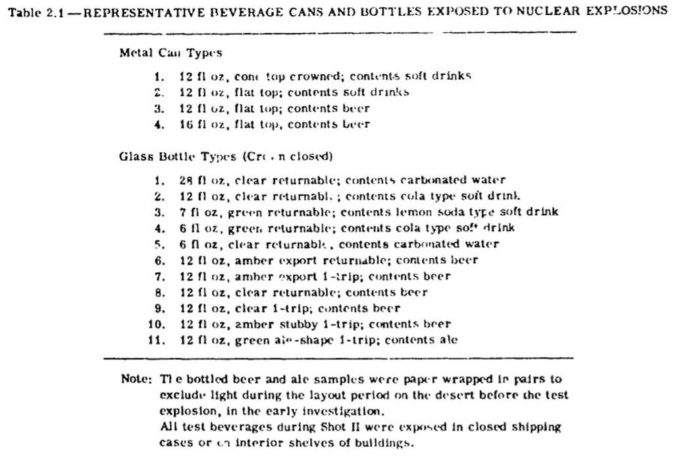

Sealed, long-lasting containers of beer and soft drinks such as ‘soda’ (fizzy pop to us English speakers) were readily available, and the AEC commented that “Packaged beverages, both beer and soft drinks, are so ubiquitous and already uniformly available in urban areas, it is obvious they could serve as an important source of fluids.” Once they had realised the need for a water substitute was as or more important than food, despite having little left in the budget to stock up, a few humble servicemen were dispatched on a local shopping spree to rustle up supplies and a new sub-category, Project 32.2a, was hastily added into the testing protocols.

Therefore, in April and May of 1955, the Americans set to and nuked the hell out of canned and bottled beer and a whole lot of other commodities at the Nevada Proving Grounds.

An entertaining point jumped out at me from the AEC’s report. As the table below shows, quite a few of those bottles were ‘returnable’. I do have to wonder whether anyone ever collected those deposits and, if so, whether they confessed where the bottles had been to the poor shopkeeper?

Of the fourteen atomic explosions, only two were selected to test the effects on foodstuffs. The first, named MET was a tower detonated device with the blast taking place on April 15, 1955. Comparable to the Fat Man plutonium-only weapon that exploded over Nagasaki, it produced a yield of 22kt. However, in typical FUBAR fashion, the designers at Los Alamos substituted an experimental core, the first core to include uranium along with plutonium, without getting around to letting the Department of Defense know. Unfortunately, the yield was 33% less than expected, which put the kibosh on many of the military’s carefully planned tests!

Public domain, Photo courtesy of National Nuclear Security Administration / Nevada Field Office

The second, somewhat more successful test was named Apple-2. Set off on May 5, 1955, this was a rehash of Apple-1 in which the primary had failed. A 29kt device was detonated after being placed on top of a 500-foot tower. One of its main aims was to test the effects of a nuclear explosion on different construction types, essential facilities and items used in every-day life. To this end, an assortment of buildings, including five distinct forms of houses, and essential services such as petrol and LPG tanks, power lines, electrical substations, and radio transmitters, were erected at a site nicknamed ‘Survival Town’.

There’s a short 1955 film about the blast, broadcast at the time and well-worth watching, called ‘Operation Cue’. This was distributed by the Federal Civil Defense Administration and can be seen at:

Both indoor and exterior spaces were populated with fully dressed mannequins (after all, you could hardly use real people!), the houses were equipped with typical household furnishings and appliances, and stocked with a wide range of canned and packaged foods. As we’ve seen, not only beer, but fresh and frozen meat, butter and other perishable foodstuffs were included in the tests.

Three locations were used for the food tests, ranging from 0.2 miles (just over 1,000 feet) to 2 miles away from ground zero, and as many variables as possible were considered. The AEC’s official report has swathes of tables specifying the conditions. Beer and soda, both bottled and canned, were buried, wrapped in brown paper to protect from light, left on the ground, put on concrete or brick shelves, placed in or on top of refrigerators, and in every case the distance from ground zero was carefully recorded.

Public domain

Not all of the buildings were completely destroyed in the blast. Three of those ‘typical American’ houses built for the Apple-2 civil defence testing event still stand at Area 1 of the Nevada Test Site. Periodically, there are free Nevada National Security Site (NNSS) public tours of the site, although the waiting list is said to be quite long. Perhaps inevitably, in the current circumstances, the public tour dates for at least the first half of 2021 have been put on hold. I’ll admit that I found it interesting that the radioactivity present on the ground at the site now offers a ‘radiologically contaminated environment for the training of first responders’—make of that what you will.

Back to that beer and, incredibly, most of the of beer (and the soda) survived both the MET and Apple-2 blasts. The AEC report explains that “These commercially-packaged soft drinks and beer in glass bottles or metal cans survived the blast overpressures even as close as 1270 ft from ground zero”. Where it didn’t survive, the destruction was largely down to “flying missiles, crushing by surrounding structures or dislodgement from shelves.”

Given that the closest beverages were just over 1,000 feet away from a nuclear blast, almost unbelievably, there were some human tasters on hand to perform ‘immediate taste-tests’. Further samples were also taste-tested under carefully-controlled conditions by no less than five ‘qualified laboratories’. Hmmm, nice job, if you can get it.

The AEC concluded that “Immediate taste tests indicated that the beverages, both beer and soft drinks, were still of commercial quality, although there was evidence of a slight flavour change in some of the products exposed at 1270 ft from GZ [Ground Zero]. Those farther away showed no change.” In terms of radioactivity, it appears that the “induced activity of the container, whether metal or glass, did not carry over to the contents” with the radioactivity being “well within the acceptable 10 day emergency tolerance.” Alright, I guess that’s reassuring, eh?

Whilst my rabbit-hole ramblings might not have helped me solve my water storage dilemma, at least I can now happily report that if Armageddon does ensue, it’s good news—alcohol should survive the apocalypse! Those nuked brews should be fine to keep you hydrated, at a pinch. Any Hooky (or indeed Stella) you have carefully squirreled away won’t hurt you… at least in the short term.

© Zepfanman.com, and Jacob Spinks, both licensed under CC BY 2.0 Combined and annotated.

© SharpieType301 2020

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file

Audio Player