Most of us, if asked, would be able to name a fair number of WW1 poets and writers without too much hesitation. Wilfred Owen, Siegfried Sassoon, Edmund Blunden, Robert Graves, Rupert Brooke, Isaac Rosenberg – the roll call of the literary (as opposed to the purely historical and military) output of The Great War is extensive and continued for twenty years after the Armistice. Guy Chapman’s A Passionate Prodigality, arguably the finest prose reminiscence to come out of the experiences in the trenches, was published as late as 1936. The literary education that underpinned the officer men who went to war in 1914 was promulgated through a system that held classical Greek and Latin texts in high esteem. The contemporary yearbooks of both major and minor public schools were replete with the names of pupils that had been commissioned officers and whose lives ended in the trenches of Flanders, the heights of Gallipoli or the sand dunes of Iraq. Their ages – mostly late teens or early twenties – had been no barrier to their advancement as officers. For many years the accepted paradigm has been that of naive young men – officers and infantry alike – pushed on by elderly generals unaccustomed to the nature of a new kind of war fought in trenches and that the poetry and prose that surfaced both during and after the war was uniformly anti-war. As Elizabeth Vandiver shows in her masterly work (see footnote) this was not the case and that an equal amount of the literary work produced by those who went through the experience was produced in unironic terms and was supportive of the concepts of honour, glory and duty. The mention of “war poets” in connection with WW1 is now uniformly heard as “anti-war” poets and this perception has been successfully cultivated through university and schools for decades. The reality was somewhat different.

It was only the arrival of WW2 in 1939 that finally brought to an end the reflections on the first upheaval in western civilisation of the 20th century. Another war was now upon the next generation and once more the writers swopped pen for sword but I suspect there are very few amongst us who could name a single poet of the later conflict. While such writers as Evelyn Waugh and Joseph Heller were to revisit WW2 in the 50’s and 60’s with Men at Arms and Catch-22 the style was blackly satirical and humorous. Paul Fussell in his admirable work The Great War and Modern Memory quotes from a writer of WW2: “ The behaviour of the living and the appearance of the dead were so accurately described by the poets of the Great War that every day on the battlefields of the western desert…their poems are illustrated.” That writer was Keith Douglas.

Keith Douglas was born in 1920 and had a fairly unhappy childhood. His mother had a debilitating illness and his father finally left the family in 1928 after which Keith was never to speak to him again. He was fortunate to pass the entrance exam to Christ’s Hospital, Horsham in 1931 and through the generosity of the bursary scheme he was able to study free of charge right through to 1938 although a brush with authority in 1935 when he stole a rifle from the CCS armoury almost had him expelled. In 1938 he won a scholarship to Merton College Oxford. Douglas had already been writing poetry at Christ’s Hospital and his work at Merton was highly praised. On the outbreak of war Douglas immediately applied for a commission and although he had to wait until July 1940 he was finally accepted into Sandhurst from which he passed out 6 months later and then posted to the Middle East spending time both in Syria and Palestine. By May 1942 he was in Cairo and was negotiating with the Tamil poet, Tambimuttu, to have some of his poetry published in a new venture Poetry London that had just been launched. His first poems were published in that magazine in October 1942 just as the Battle of El Alamein was beginning and although Douglas was under strict orders to remain at HQ to continue camouflage training – a job he disliked intensely – he decided to abscond and join his old regiment in the thick of the fighting at El Alamein. He wrote:

“The battle of El Alamein began on the 23rd of October 1942. Six days afterwards I set out in direct disobedience of orders to rejoin my regiment. My batman was delighted with the manoeuvre. ‘I like you, sir’ he said, ‘you’re shit or bust, you are.’ This praise gratified me a lot.”

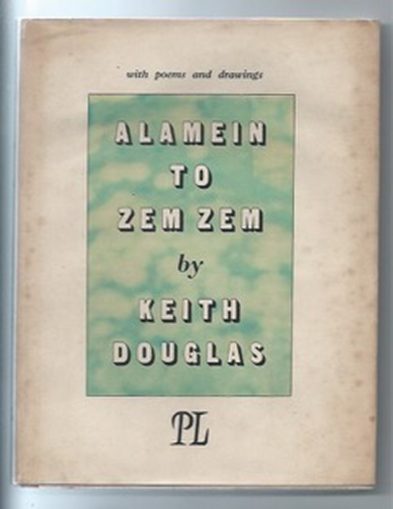

Although he had made plans in the event of a very likely court-martial he was lucky to escape such a fate by fooling the general to whom he reported at El Alamein and since the battle was in full flow by then he quietly joined his regiment and no more was said. To get a real sense of the N.African campaign seen through the eyes of a tank officer there can be no better book than Douglas’ own From Alamein to Zem Zem which he wrote while recuperating in Palestine after being wounded on 15th January 1943.

All the time he was writing poetry and his observations on the dead of the battlefield. He had developed a detachment from the bodies that he encountered or as another critic has noted a “helpless insensitivity” towards the enemy that he had killed. He is both the murderer and the victim and in such a poem as Vergissmeinnicht (Forget Me Not)** the poet is the tank commander who has attacked an Italian gun emplacement. Three weeks later he passes the same spot and finds that one of the defenders’s bodies is still there but has now been desiccated by the desert sun. He picks out a small picture from the dead man’s blouse and sees that it is a photo of a lover – Steffi is the name on the back of the photo – and he muses objectively on the nature of memory and compassion for the innocent who has been delivered of “mortal hurt” – the very mortal hurt that he himself was the author of some weeks before. Here we may see the essential difference between the war poetry of WW1 and that of Douglas. Steeped in the vast literary heritage that emanated from the first conflict – his Merton College tutor was none other than Edmund Blunden whose Undertones of War had already become a classic and who had edited Wilfred Owen’s poems for publication – Douglas entered the metaphorical trenches of WW2 with a deep understanding of what war means. Unlike the innocents that merrily marched off to war in 1914 Douglas and his generation knew exactly what was facing them. H.M.Tomlinson (another writer from WW1) wrote in 1935 that “the parapet, the wire, and the mud are now permanent fixtures of human existence” proof that the first Great War had bequeathed a permanent state of anxiety and a sense that life itself was cheap and worthless. (Parenthetically I can add as personal evidence here that my grandfather who, prior to WW1 was destined to take over his father’s highly successful accountancy business was, on his return from Flanders, unable to concentrate on anything for any period of time and drifted through meaningless jobs for the rest of his life). Douglas, and many like him, were steeped in the literature of the previous twenty years and were surrounded by the very visible human suffering – fatherless families, physically damaged men and a society psychologically scarred.

Douglas returned to England in December 1943. He was among the first on to the Normandy beaches on D-Day 1944 and his tank corps pushed forward through the Normandy bocage. Three days later, whilst surveying a field over which he planned to cross and standing outside his tank he was hit by a mortar shell which took off half his head. He was buried under the hedge of the field on which he died but later his body was exhumed and moved to the military cemetery at Tilly-sur-Seules where he now lies. He was 24 years of age.

Mention “war poetry” and immediately we envisage the Somme and Passchendaele. It is as if our modern memory has skipped back two/three generations and we can only concentrate on that which happened a century ago. Even writers who experienced the second world war were eventually to make reference back to the first but a writer such as Douglas, killed before war’s end, is worthy of much more attention. In his words we will see the thread that runs from classical literature – Homer, Aeschylus, Virgil – through the writers of the first war and which was to find a dying echo in those who fought – and died – in the second.

Romain Bréget, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

*I take the title of this piece from Elizabeth Vandiver’s admirable work Stand in the Trench, Achilles (OUP, 2010) which addresses the role of classical works of Ancient Greek and Latin in British Poetry of the Great War.

**A reading of Vergissmeinnicht can be found on Youtube. BBC documentary, Keith Douglas, Battlefield Poet.

© Roger Ackroyd 2022 Republished from 2017

Buy ‘A Coin for the Hangman’, Ralph Spurrier (Roger Ackroyd)