Published by Quill, an imprint of William Morrow & Co. 1988 paperback edition (first published 1987)

ISBN 0-688-07951-2

Internet Archive Book Images [No restrictions], via Wikimedia Commons

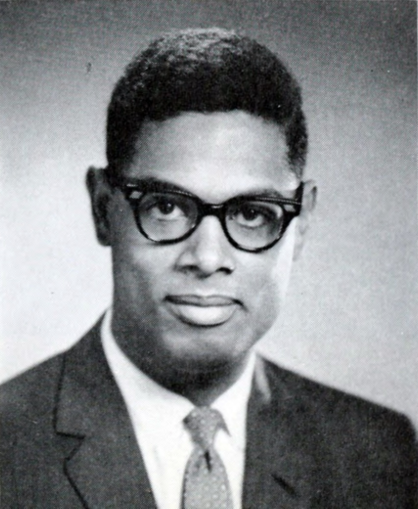

In the previous part of this review and discussion, we looked at Part I of Thomas Sowell’s book, where he examines the patterns pertaining to the constrained and unconstrained visions, as well as contemporary examples that show why the book remains relevant today. This time, we look at Part II of the book, where Sowell examines the applications of the visions. As with the previous part, this will be illustrated by contemporary examples to put the visions in current context.

[Note: As last time, spellings and punctuation in any quotations are taken directly from the book and are thus in the American form. Italics in the quotations are also as presented in the book.]

Part II – Applications

Visions of equality

Equality can also be conceived in different ways by the two opposing visions. For the constrained, it is a process characteristic and for the unconstrained it is a result characteristic.

As Sowell notes, Edmund Burke said that “all men have equal rights; but not to equal things.” Alexander Hamilton spoke in similar terms, acknowledging equality of rights but also indicating that as long as there was liberty there would also be inequality. Friedrich Hayek spoke of “irremediable inequalities” as there was “irremediable ignorance on everyone’s part.” Sowell also quotes his mentor, Milton Friedman:

“A society that puts equality – in the sense of equality of outcome – ahead of freedom will end up with neither equality nor freedom. The use of force to achieve equality will destroy freedom, and the force, introduced for good purposes, will end up in the hands of people who use it to promote their own interests.” [p. 122]

But to the unconstrained, such dangers are avoidable, if they even exist.

Although people often draw a distinction those who believe in equality of opportunity and equality of outcome respectively, Sowell points out that “equality of opportunity” or “equality before the law” does exist for both visions but it means different things to them. For the constrained, it means there is equality as long as the process treats everyone the same way. But to the unconstrained, if the situation is applied to those with differing levels of wealth, education, past opportunities or cultural orientations, this negates the meaning of equality:

To them equality of opportunity means equalized probabilities of achieving given results, whether in education programs, employment or in the courtroom. [p. 123]

Sowell quotes George Bernard Shaw ridiculing the notion of formal equality of opportunity:

“Give your son a fountain pen and a ream of paper, and tell him that he now has an equal opportunity with me of writing plays and see what he says to you!” [p. 124]

In terms of causation, unconstrained figures like Shaw and William Godwin saw great unfairness in some people earning more than others, especially when doing less work, and the idea of a zero-sum game where one party gains at the expense of another. But as Sowell shows, disgust at inequalities is not restricted to the unconstrained – Adam Smith and Milton Friedman also expressed revulsion at such things. But whilst they were willing to propose schemes to help the poor, “neither was prepared to make fundamental changes in the social processes in hope of greater equalization.” They didn’t assume such misfortunes were due to the social system either – they believed ordinary people, not the wealthy, were the main beneficiaries of material abundance in capitalist nations.

Sowell refers to the central theme of Friedrich Hayek in The Road to Serfdom; namely that the danger of seeking ever more equality in economic outcomes is that it leads to greater inequality in political power. Hayek didn’t see democratic socialists as planning despotism themselves, but as paving the way for it nevertheless, regardless of how humane their intentions. Law and political power were undermined in, to use one of Hayek’s phrases from a later work, “the mirage of social justice”. Hayek also criticised those with the notion of a “personified society” with intention, purpose and moral responsibility, where in fact society simply evolved, thus “the particulars of a spontaneous order cannot be just or unjust.”

So the two visions, although they differ on moral conclusions, do not differ on moral principles but rather in how they view causes and effects.

As Sowell notes, Smith and Godwin could agree completely on the innate equality of human beings. Smith was opposed to slavery on both moral and economic grounds and he disliked the way that royals, aristocrats and others in high positions were practically worshipped by some. But they differed in the way they viewed man and social causation.

These differences however, can lead those of the unconstrained vision to view those of the constrained vision as being in favour of inequality, through philosophic views or self-interest. But for the constrained it is possible to fight for things like advancement of groups and still be opposed to process changes.

In fact, the unconstrained have at times displayed rather disdainful attitudes towards the masses:

In an eighteenth-century world where most people were peasants, Godwin declared that “the peasant slides through life, with something of the contemptible insensibility of the oyster.” Rousseau likened the masses of the people to “a stupid, pusillanimous invalid.” According to Condorcet, the “human race still revolts the philosopher who contemplates its history.” In the twentieth century, George Bernard Shaw included the working class among the “detestable” people “who have no right to live.” He added: “I should despair if I did not know that they will all die presently, and that there is no need on earth why they should be replaced by people like themselves. [p. 136]

The unconstrained vision doesn’t entirely fit with the political left, though Sowell notes it is at home there, but this passage does bring to mind the claims by some leftists that their side is compassionate and tolerant, when their words and actions can betray the opposite tendencies. Regarding the EU referendum, which, as noted in the first part of this review, certainly wasn’t simply a left-right divide, this tendency has manifested itself in a number of ways but the attitudes of certain Remainers towards Leave voters can again be seen in terms of this side of the unconstrained vision, where the latter were looked down on, not only because of age, skin tone or lack of education but also on account of being working class, or ‘poor’.

There was a class divide element to the EU referendum, with the middle-class were more likely to support Remain and the working class were more likely to support Leave. Roger Eatwell and Matthew Goodwin, in their book National Populism: The Revolt Against Liberal Democracy [p. 214-5] wrote about the sense of relative deprivation triggered by the wider economic environment that has drawn people to national populists like Donald Trump and Nigel Farage as being motivated by a sense that their group had lost out to more affluent middle-class citizens or to immigrants. In this view, there was a sense among working class people that they were being overlooked and they wanted their voices to be heard. Claims by middle-class Remainers to be having a ‘People’s March’ and seeking a ‘People’s Vote’ in order to overturn the democratic decision in the referendum that went against their wishes have been duly scorned by Leavers. Such people have been generally mocked, not only for their condescending attitudes towards the working class but for being self-interested and out-of-touch:

PLEASE RETWEET THIS AND HELP SAVE THIS POOR REMAIN MINDED LADY FROM A FATE WORSE THAN NOT KNOWING WHO WILL BE SERVING HER COFFEE IN PRET AFTER BREXIT.

Please retweet generously to help her and millions of devastated Remainer just like her. pic.twitter.com/j6flHaoxfe

— The Core (@SocialM85897394) May 1, 2019

While the unconstrained vision seeks greater equality for people in terms of the benefits of society, it sees people’s capabilities as far more unequal than the constrained vision does. Constrained economists like P. T. Bauer held greater faith in the abilities of people in the Third World if allowed to compete in the marketplace than the unconstrained like Gunnar Myrdal, who felt them to be hopelessly backward and only able to be redeemed by the educated elite.

Today, some Remainers claim that Leavers are racists, yet it is the policies of the Remainers’ cherished EU that discriminate against people in poorer and developing nations, whilst supposed ‘racist’ Leavers like Nigel Farage have welcomed the idea of forging better links with countries where people of darker skin colours happen to come from. The EU prefers aid to trade, which is in keeping with the unconstrained vision but for the constrained such a policy will never provide the incentives that are needed for the poor to progress.

Thus the unconstrained, although having high expectations of potential intelligence of humans, have less faith in current intelligence than do those with the constrained vision. As Sowell notes, this comes down to the logic of each vision.

It is not over the degree of equality that the two visions are in conflict, but over what it is that is to be equalized. In the constrained vision, it is discretion which is to be equally and individually exercised as much as possible, under the influence of traditions and values derived from the widely shared experience of the many, rather than the special articulation of the few. In the unconstrained vision, it is the material conditions of life which are to be equalized under the influence or power of those with the intellectual and moral standing to make the well-being of others their special concern. [p. 140]

Visions of power

For the unconstrained, social decision-making has a greater importance than for the constrained regarding power. The unconstrained are morally offended at what they see as deliberate exertion of power, whereas for the constrained systemic processes cannot be explained much by power.

Neither of the two visions necessarily favours force and both prefer articulated reason, but they differ as to how far such reason will go. For the unconstrained, war is irrational. For the constrained, war is perfectly rational from the perspective of those who see gains. Rather than urging restraint, toning down language, restricted arms, etc. as the unconstrained would, the constrained seek to warn against provocations, stoke patriotism, build up arms as a deterrent, etc. For the constrained, special causes of war are rejected; war is caused by human nature and contained by institutions. For the unconstrained, war is counter to human nature and caused by institutions:

Within this vision, the military man was a lesser man for his occupation. [p 145]

Again, whilst the unconstrained view is not automatically left-wing, the proximity of the two would explain partially why such attitudes are generally more prevalent among left-wing political parties. For example, throughout its history, the Labour Party has at times had strong pacifist and anti-war tendencies, with figures like Keir Hardie, and George Lansbury, whilst Michael Foot (despite his attacks on appeasement in the satire Guilty Men) and Jeremy Corbyn were supporters of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament which advocated unilateral nuclear disarmament. The Labour Party has more recently been accused of disdain for the military and for service veterans. The Tories under Theresa May were hardly innocent of displaying disregard for veterans either. That said, for the Labour Party the tendency is more notable, although for current leading Labour figures like Jeremy Corbyn and John McDonnell there is the matter of links to Irish Republicans too, which can probably be attributed in part to certain interpretations of radical Marxism, anti-imperialism, etc. that do not necessarily have much to do with the unconstrained vision.

Nonetheless, the historical pacifistic, anti-war and anti-nuclear stances of Labour are in line with the unconstrained view as referred to above (e.g. urging restraint, toning down language, restricted arms) and would naturally result in, at the very least, a difficult relationship with the military. Meanwhile, right-wing parties are more likely to favour the opposing, constrained view, which tends to embrace patriotism and the importance of the military, without this necessarily making them pro-war. But for the constrained there seems to be a deep respect for the military too. Adam Smith believed the demands and responsibilities of the soldier elevated him, in spite of any perceived diminution of humanity caused by having to kill other men. This was an acceptable trade-off.

With crime too, the unconstrained seek the underlying causes, whereas the constrained seek no such causes and attribute it instead to human nature. For Godwin, if someone was healthy and rational, they should have no cause to commit crime and the best way to reduce the chances of crime would be by reducing poverty, unemployment, mental illness, etc.

The two visions both acknowledge that most people are appalled by certain crimes but the reasons differ: for the constrained, this is due to social conditioning, a sense of general morality cultivated by traditions and institutions; for the unconstrained, human nature itself is averse to crime:

From this perspective, criminals are not so much the individual causes of crime as the symptoms and transmitters of a deeper social malaise. [p. 148]

For the constrained, there are so many incentives to commit crimes that counterincentives are necessary, through moral training and punishment. The constrained see punishment as a painful duty, but the unconstrained see it as vengeance, therefore making criminals double victims, of both the circumstances that provoked the crime and the punishment received afterwards. Recent Labour Party proposals to use non-custodial sentences rather than prison for certain types of offences reflect this view.

For the unconstrained, the dominant influence in society should be the best people who use articulated knowledge and reason. But if the knowledge and wisdom of the few does not reflect the decisions of the many, decision-making powers may end up reserved more under the control of those deemed to have wisdom and virtue. The unconstrained vision can thus go from anarchic individualism to totalitarianism. The constrained don’t believe that man can plan and execute social decisions for the common good: instead, incentives through systemic processes, leading to e.g. trade-offs, are key. This is not to say that individuals cannot make their own choices – as per Milton Friedman’s classic work Free to Choose they can – but they are made within constraints, with incentives, and shaped by shared experiences and values. Both believe in individualism but have different conceptions of it.

But in the unconstrained vision, individualism refers to (1) the right of ordinary individuals to participate in the articulated decisions of collective entities, and (2) of those with the requisite wisdom and virtue to have some exemption from either systemic or organized social constraints. [p. 153]

Sowell notes that John Stuart Mill’s On Liberty exemplified the second point. The moral-intellectual pioneers could be exempted from social pressures of mass opinion, though not vice-versa. In fact, for some of the unconstrained view, this exemption even applies to laws, e.g. conscientious objectors. Again, we can see viewpoint of Remainer MPs and intellectuals, where they evidently feel that they are not bound by the views of the masses.

The same thinking applies to the economy. The constrained see the market being efficient in the way that prices reflect information, supply and demand, etc. But the unconstrained believe that it is controlled by particular interests and needs to be made to obey the public interest. One side sees it in terms of intentions and the other sees it in terms of incentives.

In the law too, the conflict arises. For the constrained, once laws had drawn up the boundaries of discretion, courts should not second-guess the exercise of that discretion. But for the unconstrained, this would allow injustice to flourish unnecessarily and it was the role of courts to provide fresh moral insight. There have been people like Ronald Dworkin and Laurence Tribe on the unconstrained side of the argument and Oliver Wendell Holmes on the constrained. Dworkin felt the courts should go beyond the normal boundaries and exercise their own discretion.

Visions of justice

For the unconstrained, justice is paramount with the rights derived from it inhering in individuals and for individuals. It is not to be traded off. Rights based on justice are “trumps” that prevail over other social considerations. For the constrained, justice obtained its importance from the need to preserve society, but society did not gain its purpose by producing justice. Justice had to be subordinated to order, otherwise society would suffer from the breakdown of order. People might even have to suffer some injustices if order is to be preserved because disorder would ultimately cause greater suffering.

In legal justice, Oliver Wendell Holmes, favoured the constrained view:

Holmes said, “justice to the individual is rightly outweighed by the larger interests on the other side of the scales.” He opposed “confounding morality with law.” Law existed to preserve society. Criminal justice, for example, was primarily concerned with deterring crime, not with finely adjusting punishments to the individual. [p. 176]

Although Holmes did not deny the contribution of great minds to the development of law, nor did he fatalistically accept all laws that existed, nor even deny that there was logic in the development of law, he did oppose the idea that it had evolved by the application of logic. Rather it “represented the evolved and codified experience of vast numbers of people”. The eighteenth century English legal theorist William Blackstone said that “considering all cases in an equitable light must not be indulged too far, lest thereby we destroy all law, and leave the decision of every question entirely in the breast of the judge.” Law without equity, even if disagreeable, was better than equity without law. Blackstone felt that due to human frailty, reason in itself was insufficient to create law. He also said:

“And it has been an antient observation in the laws of England, that whenever a standing rule of law, of which the reason perhaps could not be remembered or discerned, hath been wantonly broke in upon by statutes or new resolutions, the wisdom of the rule hath in the end appeared from the inconveniences that have followed the innovation.” [p. 178]

In terms of recent events, like the overturning of Parliamentary conventions by Speaker John Bercow, the so-called ‘Benn Act’, designed to force the government to request an extension from the EU and to accept what it offers, legal challenges to Brexit and the decision of the Supreme Court in declaring the Prime Minister’s prorogation of Parliament ‘unlawful’, the words of Holmes and Blackstone resonate strongly today. Leavers might see the overturning of long-standing conventions as being carried out in pursuit of short-term, politically-motivated gains, whilst viewing the Benn Act as unconstitutional, and the legal challenges and the Supreme Court decision as ignoring the long-term constitutional consequences of such actions and creating the precedent for a judicial power grab. Remainers have spoken about the importance of the government following “the rule of law” but as Dr. David Starkey noted recently when speaking with fellow Leaver Brendan O’Neill, “The rule of law bears an extremely strong resemblance to the rule of lawyers…”:

During the same podcast, Starkey and O’Neill touch on several of the same subjects raised here, including the views of William Blackstone. They also discuss the decisions of both Conservative and Labour governments that have had an impact on legal accountability: in the case of the former, to undermine local legislative power; in the case of the latter, the effective abolition of the office of the Lord Chancellor (a position which continues but in name only). It is worth bearing this in mind because outside of Brexit too, MPs have been seen as having rushed into making ill-considered laws for self-serving political considerations without grasping the potential consequences nor respecting traditions which existed for important reasons. Tony Blair’s government in particular, as recently alluded to on this very site, saw the passage of greater numbers of new laws than his predecessors and it has been argued this was done without effective Parliamentary oversight.

But to return to Sowell, for Holmes and Blackstone then, evolved systemic rationality rather than individual explicit rationality was superior. There was also the sense of trying to keep, where possible, within the spirit of the law that existed at the time when it was made.

Godwin felt that men could not be reduced to the same stature for a crime. However, there was no difference in values between him and Holmes: both felt the moral superiority of being able to individualise punishments but Holmes simply regarded it as unrealistic, beyond human capability. Godwin believed that incentives of reward and punishment were a distraction from the real reasons criminals behaved the way they did. Moral improvement was what was necessary, to change people’s motives and predispositions and thus render incentives unnecessary. The unconstrained reject the constrained notion of processes because they feel that processes have disparate impacts on different groups and that any professed ‘neutrality’ is in fact illusory and hypocritical.

For commentators like Laurence Tribe, existing constitutional doctrines that perpetuated “unjust hierarchies of race, gender, and class” were offensive. (These views, written in the 1980s, would fit well with the social justice movements of today.):

… Tribe criticized court rulings which upheld the legality of applying certain physical standards to particular job applicants, regardless of sex, “blithely ignoring sex-specific differences that make the ‘similar’ treatment of men and women invidious discrimination.” [p. 184]

As Sowell notes, Tribe didn’t argue that “anything goes”. But if a judge is allowed to make a determination on such a matter, and rights trump interests, including the general interest, from the constrained perspective, no individual should make a determination on specific social results.

As for individual rights, there are differences in the conception of both visions as to what ‘rights’ actually mean. For the constrained, rights provide “zones of immunity from public authority” but with benefits that are social, e.g. property rights, which give efficiency, ease and greater influence to individuals than centralised authority can. Free speech is another such area, deemed to serve a public interest. For Holmes, who, “urged eternal vigilance against the suppression of opinions considered loathsome and dangerous” free speech could only justifiably be curtailed when it posed a “clear and present danger” to the public interest.

For the unconstrained, property rights should not be exempt from intervention by public authority, although free speech rights should be. For those like Tribe, the focus should be on the social results of the distribution of property; as for freedom of speech, it is not really deemed ‘free’ if people have to resort to expensive methods to get their messages out, rather than simply being able to speak in a public square or distribute relatively inexpensive leaflets as used to be the case. The cost of electronic broadcasting, direct mailing, newspaper advertising, etc. is large and not possible for all. Presumably this view still applies, although in the internet age it might have changed to a degree with social media and crowd-funding levelling the playing field to an extent, but in the era of ‘privilege’ anything that is deemed to give someone an ‘unfair’ advantage is fair game for criticism. If anything, people of a similar mindset – if not fully of the unconstrained vision then certainly of the left/liberal persuasion, a group who were once such staunch defenders of free speech – would now seem more likely to censor and deplatform those they disagree with. It seems even the leader of the free world is not immune from people making such attempts against him:

Senator Kamala Harris has written to Twitter CEO @jack calling on him to suspend President Trump’s Twitter account pic.twitter.com/vOEIua2rQh

— Yashar Ali 🐘 (@yashar) October 2, 2019

On the topic of social justice, Sowell notes that William Godwin’s Enquiry Concerning Political Justice from 1793 is perhaps the first book dealing with the subject and he believed we all have a responsibility to contribute to common advantage:

He rejected “the supposition that we have a right, as it has been phrased, to do what we will with our own.” He denied its premise: “We have in reality nothing that is strictly speaking our own.” [p. 190]

However, this was a moral claim, not one seeking governmental control. It was compatible with laissez-faire thinking because it did not seek the government to compel people. But as Sowell says, it is not difficult to see how such thinking could lead to others seeking government intervention. Again though, it shows the unconstrained vision doesn’t entirely match the political left, who would tend to be more in favour of government intervention in the economy and regarding property rights.

Social justice has been a dominant issue for the unconstrained and like other unconstrained issues is a results-based one. For the constrained, it is not an issue. The constrained might consider process issues of income distribution but do not believe that “one income distribution result is more just than another”.

Both visions have shown concern for the less fortunate – slavery was opposed by Burke and Smith as well as by Godwin and Condorcet; schemes of income transfer to the poor were favoured by both Friedman and Shaw. It is not that one vision favours the poor and the other doesn’t. The difference is that the unconstrained vision sees transfers of material benefits to those less fortunate as justice:

Central to the concept of social justice is the notion that individuals are entitled to some share of the wealth produced by a society, simply by virtue of being members of that society, and irrespective of any individual contributions made or not made to the production of that wealth. [p. 192]

Although Godwin acknowledged that religion had led people to believe in principles of justice, he thought too many rich people treated charity as a spontaneous act of generosity that made them feel good about themselves and caused the poor to be made to feel that they were beneficiaries of the good grace of others rather than what they were due. Shaw felt the same and spoke of the “pride” of the rich and the “humiliation” of the poor, leading to hatred between the two.

Hayek, an exception among leading constrained thinkers in discussing the issue (most viewed the matter as too futile to merit discussion) saw social justice as “absurd”, a “mirage”, “a hollow incantation”, “a quasi-religious superstition”, and a concept that “does not belong to the category of error but to that of nonsense”. He objected to the idea that political power should determine rewards. He didn’t object to the notion of alternative results but felt that the attempt to create such preconceived results can bring about processes that “can destroy civilization”:

According to Hayek, the phrase ‘social justice’ is not, as most people probably feel, an innocent expression of good will towards the less fortunate,” but has become in practice “a dishonest insinuation that one ought to agree to a demand of some special interest which can give no real reason for it.” The dangerous aspect, in Hayek’s view, is that “the concept of ‘social justice’… has been the Trojan Horse through which totalitarianism has entered” – Nazi Germany being just one example. [p. 195]

Consider today’s social justice movement. In the infamous interview of Dr Jordan Peterson by Channel 4’s Cathy Newman, Peterson spoke of the dangers of the kind of philosophy that drives people like trans-activists as being the same philosophy that led to left-wing totalitarian regimes that resulted in millions of deaths, much to Newman’s apparent incredulity. Peterson highlighted the dangers of identity politics and of treating group identity as paramount:

Hayek witnessed the rise of totalitarianism. Also, to him the emphasis of blaming certain ills on the ‘actions’ of society was absurd because it was the idea of demanding justice from a process, something which could not be personified to attach blame to it.

The hidden – and dangerous – significance of the demand for social justice, in Hayek’s view, was that it implied a drastic change in whole processes under the bland guise of a mere preference for better distribution… “the demand for ‘social justice’ becomes a demand that the members of society should organize themselves in a manner which makes it possible to assign particular shares of the product of society to different individuals and groups.” [p. 196]

Hayek felt the greatest danger was that replacing “formal” justice with “social” justice led to the undermining and ultimate destruction of the rule of law by allowing government powers to expand into areas they were once exempt from:

While Hayek regarded some advocates of social justice as cynically aware that they were really engaged in a concentration of power, the greater danger he saw in those sincerely promoting the concept with a zeal which unconsciously prepares the way for others – totalitarians – to step in after the undermining of ideological, political, and legal barriers to government power makes their task easier. [p. 197]

Visions, values and paradigms

A vision is not a paradigm – a more intellectually developed notion – but “an almost instinctive sense of what things are and how they work.” Unlike in scientific thought, where paradigms are tested against evidence and succeed each other over time rather than coexisting, in social thought paradigms continue to coexist. Paradigms are easier to test in science and experiments which fail can be begun again but in social thought the biological continuity of the human race precludes this. In theory it should be possible to resolve the conflict of visions based on evidence but in reality it is not, for a number of reasons. Evidence can be weighted differently and subjectively, whilst the hypotheses of a vision can still survive, either in a less extreme or more complex form.

“Evidence is not irrelevant, however. “Road to Damascus” conversions do occur, and even if it is only on a single issue, the repercussions on one’s general vision may lead to a domino effect on other assumptions and beliefs. Responses to evidence – including denial, evasion, and obfuscation – likewise testify to the threat that it represents.” [p. 206]

This perhaps illustrates why cognitive dissonance is so common. Sowell explores further in other books, like The Vision of the Anointed and Intellectuals and Society the idea that certain people often cannot let go of their visions because a vision becomes so paramount to someone’s identity that to admit to being wrong could cause huge damage to the ego and can lead someone to question their very identity. Sowell doesn’t fully go into this here but he does illustrate the high psychic cost of such a realisation. This shows the power of visions – even falsification of data can occur to support and maintain a vision, in spite of the potential for the falsification to be exposed and for evidence to the contrary to emerge, even at potential risk of loss of reputation for the person holding to the vision. But as he also states:

Evidence need not be falsified in order to be evaded… the theory may be so stated that nothing could possibly happen that would prove it wrong. In this case, the theory is reduced to empirical meaninglessness; since all possible outcomes are consistent with it, it predicts nothing. Yet, though it specifically predicts no single outcome, it may insinuate much and be enormously effective in its insinuation. [p. 208]

It can even be that ideas from one vision can be borrowed by another e.g. T. R. Malthus, who took a constrained view regarding the dangers of population increase in proportion to food supply, a view which was later taken up in modified form by the unconstrained.

While falsification of evidence is a conscious decision, evasion is not necessarily so, and misperceptions of what constitutes evidence less so. Theories may persist because sufficient skill and care are not used by someone testing the theory, who may also come at it from an opposing perspective and can only see it in their own terms. As Sowell also indicates, if someone e.g. conducts a survey and asks people how they would react in a certain situation, they may answer in a way that does not reflect how they would actually behave but they don’t want to give a negative impression. It could also be that the wrong people are being asked and a misleading conclusion is reached.

It can further be the case that evidence is neither sought nor offered. As an example of a sweeping assertion that went unchallenged for a long time, Sowell mentions how some people claim that higher rates of broken homes and teenage pregnancy among blacks are somehow a “legacy of slavery” (a claim that persists today) and how this claim ignores the fact that these things were significantly lower during slavery and in the decades following emancipation.

For these visions to become specific sets of theories and corollaries – paradigms or intellectual models – is a complicated process and can require many links. This can mean heavy emotional and possibly public identification with particular theories, which is why the failure of such theories can therefore be painful because the individual has much mental investment in them.

Furthermore, no vision or paradigm deriving from it can perfectly fit the facts and when certain information contradicts theories, said information might not be considered hugely important and can hence be ignored. Sometimes though, visions can be modified to fit the discordant evidence. Also, when believers are confronted with evidence that cannot be contradicted, “it is always possible to dismiss the evidence as “simplistic,” because the issue must be more complex than that.” Even some concessions or retreats do not mean overall defeat for a vision. But for all such difficulties, Sowell says that even to admit that there is a conflict of visions is some kind of advancement.

It is quite possible for people of the same moral values or religious views to nevertheless end up with opposing visions. This is because the visions are matters of causation, not morality.

In spite of the persistence of opposing visions, there have been many instances of people converting from one vision to another, so although there is a high psychic cost, it is not necessarily prohibitive and is probably easier when done incrementally rather than suddenly. Large numbers of political conversions after certain historical events indicate that these are changes in visions rather than in values. As to whether values precede or follow visions, Sowell believes values are more likely to derive from visions, than vice versa. But instantaneous mass conversions are unlikely and the persistence of visions for centuries in spite of evidence that may contradict them suggests they develop intellectual and psychic means of coping.

Although issues relating to visions can become emotional, visions are not based on emotion but logic – the conclusions reached are the logical outcome of the consequence of the assumptions made. Misunderstandings occur, not only due to caricatures of opponents but also because certain words can mean very different things to different people. There is also the way that the unconstrained and the constrained express their basic concepts – freedom, justice, power and equality – the unconstrained in terms of results and the constrained in terms of processes. This doesn’t mean that results do not matter to the constrained – results are, after all, justification of processes – but from that perspective it is only processes that can be gauged by man.

The clash is not a matter of degree of concepts, but of what they consist of. The historical ascendancy of one vision over another can also impact on the relationship and adherents of one vision might feel the need to take increased efforts distinguish it from the other. There is also the adversarial nature to the asymmetry with which the two visions view each other:

In the unconstrained vision, in which man can master social complexities sufficiently to apply directly the logic and morality of the common good, the presence of highly educated and intelligent people diametrically opposed to policies aimed at that common good is either an intellectual puzzle or a moral outrage, or both. Implications of bad faith, venality, or other moral or intellectual deficiencies have been much more common in the unconstrained vision’s criticisms of the constrained vision than vice versa. In the constrained vision, where the individual’s capacity for social decision-making is quite limited, it is far less surprising that those who attempt it should fail – and therefore far less necessary to regard the “mistaken” adversary as having less morality or intelligence than others. Those with the constrained vision tend to refer to their adversaries as well-meaning but mistaken, or unrealistic in their assumptions, with seldom a suggestion that they are deliberately opposing the common good or are too stupid to recognize it. [p. 227]

The kinds of attitudes, which can be seen on both sides of contemporary issues like Brexit and Trump, reflect how those of differing visions think about their opponents. For many Remainers, Trump opponents, et al., accusations of bad faith, deficiencies and the like towards their opponents are common – a quick internet search will produce many examples. For many Leavers, Trump supporters, et al., opponents might largely be seen as well-meaning but unrealistic, idealistic and not grounded in reality or aware of the natural conclusions of their policies – again, a reasonable number of examples can be found online. As with Sowell’s observation, there are personality variations on both sides, thus there can be exceptions: for instance, some Leavers or Trump supporters may attribute bad faith, venality or moral deficiencies to opponents, whilst Remainers or Trump opponents might understand the reasons for their opponents having voted the way they did and just consider them mistaken, without resort to name-calling and assuming ill motive for most of them, though instances of these attitudes are harder to find. Circumstances differ too and some claims of bad faith are not necessarily lacking in justification – depending on the situation and the parties involved, there can be valid reasons for such views. But specific instances are different from treating all opponents in such a way and as a general rule, these divides do tend to follow the same constrained-unconstrained pattern.

In the unconstrained vision, where the intellectual and moral potential of man vastly exceeds the level currently observable in the general population, there is more room for individual variation in intellectual and moral performance than in the constrained vision, where the elite and the masses are both penned within relatively narrow limits… Given the inherent limitations of human beings, the extraordinary person (morally or intellectually) is extraordinary only within some very limited area, perhaps at the cost of grave deficiencies elsewhere, and may well have blind spots which prevent him from seeing things clearly visible to ordinary people. [p. 228-9]

On a similar theme, in his book The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable, Nassim Nicholas Taleb talks about the phenomenon of what he calls ‘epistemic arrogance’, by which he means the hubris that people can display regarding the extent of human knowledge. Epistemic arrogance can lead people to overestimate what they do know and underestimate what they don’t, sometimes to the point of denial. He notes that it is a good idea to question the error rate of experts.

Given such attitudes, it is unsurprising that unconstrained academic types believe their own superiority and don’t see the value of the collective population wisdom, as the constrained do. Professor A. C. Grayling might be an expert within the realm of philosophy, but from the perspective of Leavers, why does this give the right to advocate for Brexit to be stopped if the conditions demanded by him and other Remainers are not met? Professor Brian Cox might possess scientific qualifications and televisual skills that enable him to knowledgeably present television programmes about astrophysics but why should his views on Brexit be treated with any greater reverence than the average person, let alone the collective knowledge of the majority who voted to leave the EU?

These types might be well educated, but within limited areas and as Sowell notes above, their blind spots can prevent them from seeing what ordinary people can:

Historic evasions of evidence are a warning, not a model. Too often the mere fact that someone is known to disagree widely on other issues is considered sufficient reason not to take him seriously on the issue at hand (“How can you believe someone who has said…?”) In short, the fact that an opposing vision has as much consistency across a range of issues as one’s own is used as a reason to reject it out of hand. This is especially so when the reasons for the differences are thought to be “value premises,” so that opponents are conceived to be working toward morally incompatible goals. [p. 231]

Aside from matter of emotion, logic or self-interest that may draw people towards a vision, the vision has a logic and momentum of its own. People later attracted to the vision might have very different reasons to those initially attracted to it.

Visions help explain ideological differences, which are only part of the reason for political differences, but they do shape the general course of political trends in the long run. Not all social theories fall under the unconstrained and constrained visions, but it is remarkable how many do and a range of the divides concerning the big issues of the day are explained better by such visions than by the clichéd political spectrum. Sowell provides a brilliant overview that explains these differing positions and he is a much-needed voice of sanity and clarity in a continuously fractious world where, despite the depth of feeling surrounding the latest issues and perhaps the sense that our own time in history is unique, we have seen these same divides so many times before.>

Amazon book link:

Amazon author page: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Thomas-Sowell/e/B00J5BK55K

Author’s website: https://tsowell.com

Twitter page (not the author’s own, but it regularly tweets many good Sowell quotes): https://twitter.com/ThomasSowell

© The Black Swan 2019

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file