June 9th, 1811.

At sea once more, we discovered that two of our crew had deserted, preferring the fleshpots of New York to their homeland and what will certainly be a more than generous reward from our patron Count Bagarov.

These are the first two to have ‘jumped ship’, as sailors put it – though it has to be said that our previous ports of call have offered less attractive prospects. Still, they were only two and we can get on well enough without them. As for our loyal remainder, in the words of Virgil, Cuncti adsint, meritaeque expectent praemia palmae, Let all be present and await the rewards of the well deserved accolade.

June 20th, 1811.

An uneventful voyage so far, if any crossing of the wild North Atlantic may be called uneventful. At least there have been no serious storms and the sails and rigging remain intact. We have become such hardened sea bears that we barely notice any weather short of a hurricane.

Marina is the most beautiful little white bear cub imaginable, and the darling of the entire crew. It will not be long before she surpasses Aeolus, seven months her senior – how slowly human infants grow up! One of the sailors, Yuri, is a passable painter, and has been making portraits of us all, singly and together. We are aware that the time is no longer far off when we must abandon the brotherhood of the ship in which we have lived for so long, and go our separate ways. It is a sad prospect but an inevitable one; as Heraclitus said, Πάντα ῥεῖ, Everything flows.

July 5th, 1811.

We had our first sight of England at dawn: the Lizard Point in Cornwall. Shortly afterwards were were hailed by a frigate of His Majesty’s navy, HMS Spiteful, and ordered to heave to. It was clear that they suspected us of being blockade runners, despite our flying the flag of a neutral nation, Russia. We obeyed as we must, and were boarded by a gold-braided gentleman who introduced himself as Captain Fotherington.

We had determined to make matters as difficult for him as we could, so we affected to have no speakers of English on board. As the captain came up over the side, he was daunted by finding himself passing a gauntlet of bears, five to a side, to be confronted by the equally magnificently attired Count Bagarov, and the looming figure of Captain Ulyanov who addressed him in barbarous French, a language of neither party had much command. But the threat that Sa Majesté Impériale de toutes les Russies would be seriously displeased if Fotherington pressed his enquiries too closely, and that this might provoke un incident diplomatique, had the desired effect, and he retired without insisting on searching the ship. We were indeed carrying some quantity of goods that would incur a heavy duty in England: tea from Canton and rum and tobacco from Trinidad.

The encounter gave Fred an idea. ‘Right,’ he said. ‘We bin through the blockade. Reckon it’s time to do a little tradin’.’ The Count happily agreed, and nightfall found us anchored off the coast of the Cotentin peninsula of Normandy, where Fred happened to know someone in the little village of Maupertus. This person, whose name I never discovered, provided us with forty barrels of French brandy, purchased with the Count’s apparently endless fund of silver thalers.

July 6th, 1811.

Daybreak saw us sailing briskly north-west towards Eype, the little Dorset village where we had had some unlicensed dealings two years before, and we anchored off the coast shortly after sunset and sent a boat ashore, rowed by four bears and carrying Fred, Jem and myself. The local people remembered us, especially the bears, and we were warmly welcomed and had no difficulty in finding our former partners in trade at an inn. A bargain was swiftly transacted, and we had our goods ashore soon after midnight and were on our way again. How swiftly business can be conducted when no wearisome officials stand in the way!

The Count realised a handsome profit on the day’s dealings. For all his aristocratic airs, he does not turn up his nose at financial gain. As the emperor Vespasian remarked when his son Titus delicately reprimanded him for profiting by the installation of public lavatories in Rome, Pecunia non olet, Money does not smell.

July 7th, 1811.

Alas! Good things must come to an end. Fred, Jem and I had decided that we must part with Count Bagarov in a place well to the west of London where, after all, Fred is still sought as an escaped criminal. Accordingly, we anchored at Bournemouth, a town small enough for us to avoid the attention of the forces of law but large enough for the recruitment of some sailors to man the ship on her continued voyage – though, as the Count tearfully said, ‘Nuffink can replace yer bears. Yer bin good to me, and I won’t forget yer.’ We shall take a small portrait of him with us, executed by Yuri on a piece of oak plank.

Our company of bears must also divide, for Boris, Beaivi and little Marina are going on with the Count to find a home in Archangel. Our hearts are wrenched by parting. We hugged each other as only bears can.

Indeed the good Count did not forget us. As we went ashore for the last time he pressed into Fred’s hands a heavy leather bag which we later found to contain the truly princely sum of £1000, much of it in English sovereigns from the previous day’s transaction. His noble generosity is made even more apparent by the fact that he gave us no opportunity to thank him for his munificence as he surely deserved. How we shall miss his genial presence as he encouraged us through ice and storms!

July 8th, 1811.

We passed our first night on land in a small wood outside the town. It was strange not to feel the motion of a ship or to hear the groan of the shifting timbers, the creaking of the rigging and the rattling of blocks. But it was a warm night, and the stars overhead reminded us comfortingly that we were still in the same world.

After a breakfast of rabbits and an incautious fox washed down with some rum we had brought from the ship, while Dolores nursed Aeolus under an oak tree we sat down and debated what to do. We now had enough money to settle down if we wished, but nowhere to do so. Yet it was summer and it would be easy to adopt our old nomadic life until we found a spot that suited us. We resolved to head west, simply to put as much distance between London and ourselves as possible.

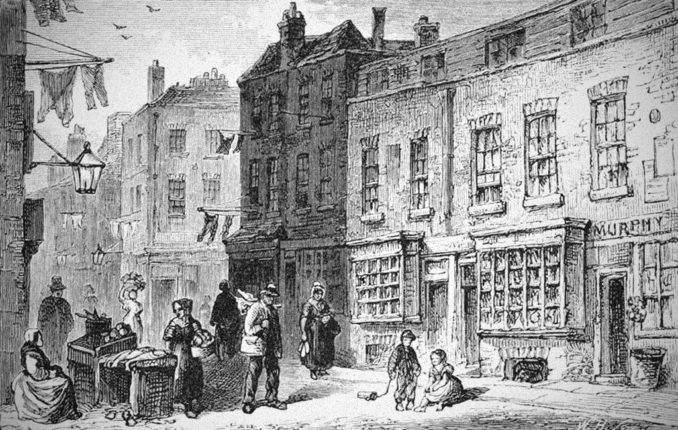

In the evening we found ourselves in Milton Abbas, a strange village consisting of identical thatched cottages disposed at equal intervals along a straight road, with a uniform horse chestnut tree between each one. We found an inn, which was off the alignment and did not seem part of the plan, and gave our customary performance, collecting a trifling amount from the local folk, which we scarcely needed – but if people are willing to pay to be entertained, they will appreciate the entertainment all the more.

Afterwards, the strange conformation of the village was explained to us. Thirty years ago there had been a village named Middleton nearby. However, the landlord, one Joseph Damer, Lord Middleton and Earl of Dorchester, had recently completed his large residence, which was visible not far away – an absurd construction of bulky blocks in the classical style superficially transformed to a parody of the medieval by the addition of pointed windows and a trimming along the top which was halfway between battlements and balustrades. This nobleman felt that the village was spoiling his view, and had it moved to a new site, razing the old buildings to the ground. While the relocated villagers mocked their landlord’s vanity, they had to concede that their new dwellings were more comfortable than their old quarters.

July 11th, 1811.

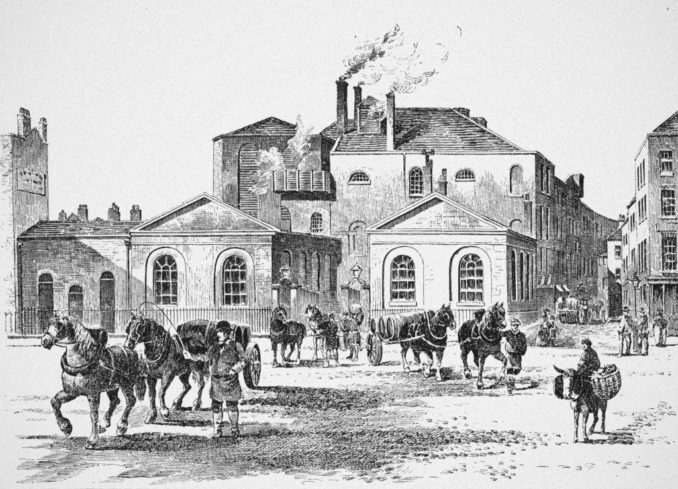

This evening, having crossed from Dorset into Somerset, we arrived in the small market town of Wiveliscombe. It is not a place of commanding grandeur, and indeed the houses seem somewhat dilapidated. However, the locality is made more fragrant by the presence of a brewery, whose ventilated storehouses and smoking chimneys we observed as we entered the town.

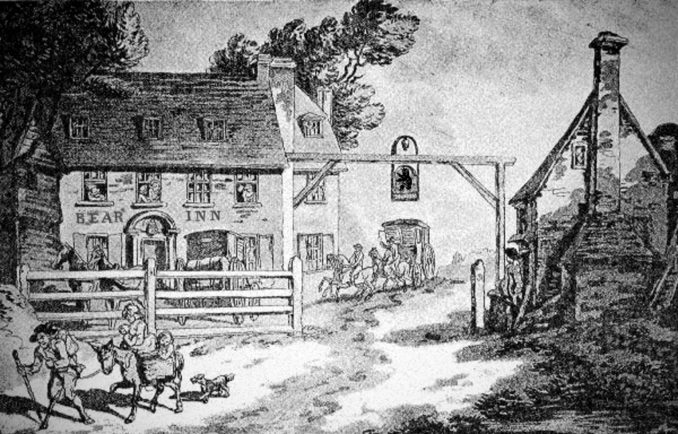

In a street a short way to the north of the market square we saw the broad gateway of a coaching inn, and a sign proclaiming its name – The Bear. Naturally we went in at once. The owner did not seem disturbed by the arrival of eight eponymous creatures, and reached for eight pewter quart mugs hanging on the wall above him. I should mention that young Henry is no longer a little bear, and is as large as any of us; the days when a discerning landlord would offer him a mere pint are long gone. Fred, Jem and Dolores were judged worthy only of pint mugs, and our host busied himself with filling them from a barrel behind the counter – Joseph Bramah’s newfangled ‘beer engine’ for drawing beer up from the cellar has not yet reached Wiveliscombe.

The ale was remarkably good – deep brown, nutty in flavour, well hopped and strong. Aeolus will sleep well tonight. Fred complimented the proprietor on his brew, and asked him if it came from the local brewery.

‘Ar,’ he replied. ‘That be Will Hancock’s works. ’E’s bin brewin’ in Wilscum (for so he pronounced the name of the town) for quoite a few years now. Truth to say, ’is ale be good enough. But Oi prefers to brew me own, the way Oi loikes it..’ He motioned use to the other side of the room, and through the back window we saw a yard with the apparatus of a small brewery. He opened a window and an enticing malty scent drifted in.

There were not many other patrons to serve – indeed fewer than the quality of his ale seemed to merit – and his demeanour was visibly tinged with melancholy. We drifted into conversation with him. He is called Cornelius Voggins. He has been a widower for fifteen years and had intended to pass the ownership of the inn and brewery to his only son Jasper, but Jasper had imprudently enlisted in the army and had been killed in the bloody storming of Badajoz in April, and now he found himself without heir or prospects.

Fred and Jem told him of our exploits of the war in Spain and Portugal, and related their experience of the atrocities of that cruel campaign, and we fell into a sad sympathy. But as we talked, I sensed that an idea was forming in their minds, as indeed it was in mine.

While Mr Voggins was drawing ale for some men who had just arrived, and sending a serving maid to fetch food for them, we conferred. Fred spoke first: ‘’Ow d’yer like the idea o’ buyin’ this place? Reckon we could give it a go?’

‘I always fancied the idea o’ bein’ an innkeeper,’ said Jem.

‘Reckon I could cope wiv the cookin’,’ Dolores said. ‘Not too ’ard in a place like this, wiv a couple o’ gals to ’elp me.’

I wrote on my slate, I would like to try my paw at brewing.

When four kindred spirits come to the same conclusion there is no need for further conference. We waited only until Mr Voggins had finished serving his customers before we approached him. Nor did he seem surprised by our offer to purchase his establishment, saying only, ‘When Oi seed all them bears come in the door, Oi knew it were the workin’s o’ the good Lord. ’E taketh away, but ’e giveth. ’Ow much are yer offerin’?’

Without overmuch haggling we settled on the sum of £250 for the building, a rambling place of some size, and another £250 for the goodwill of the business, with the condition that Mr Voggins should stay on until he had fully instructed us in the arts of innkeeping and brewing. This he was more than happy to accept, and it was cheering to see how his melancholy face brightened at the prospect of being able to pass down his skills.

We shall do our best to compensate him for the loss of his son. Also, I believe that our skill in providing entertainment will bring a flood of custom to our inn. And I shall be a brewing bear! I have mastered many arts, and I am eagerly looking forward to learning a new one.

Copyright © Tachybaptus 2019

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file