Having exhausted the train photographs to the middle of our mystery album, with care we shall turn its century-old leaves to the front. Those locomotive photos were from 1925, therefore the next set of reproductions can be assumed to pre-date the middle year of the 20th century’s third decade.

The album begins with a boat, literally decked out with tarpaulins as if tied up alongside for the night during an expedition.

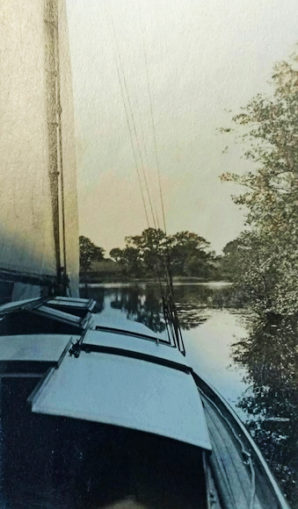

You author wouldn’t pretend to be an expert on anything that’s decorated in sails and bobbing about on wet stuff. You can be assured he knows nothing about the rigging other than that there’s a yardarm in there somewhere which promises refreshment as the sun dips below it. But he does know that boats, as with railway engines, are all the same but all different.

This one is long and thin and enjoys an extensive cabin, tall mast, shallow draft and has a rowing boat in tow. A white hull sits below what, to this landlubber, looks like a teak deck.

Although a handsomely proportioned craft, I wouldn’t like to cross the Atlantic in it or try to find the Northwest Passage. Likewise, the Queen Mary and the Erebus might struggle to moor at the shallow wooded riverbank of an idyllic English waterway. Taking these characteristics into account, even the briefest enquiry from the most lily-livered of landlubbers shows that the pictured vessel is a wherry.

Here we see a similar wherry next to a riverside building which is topped by a distinctive roof crowned with an outsized square chimney. Might it be a malthouse? And might wherries have transported to and from it along the riverways?

This windmill stands suspiciously atop a sluice gate. Might we assume it was pumping water rather than milling corn? By now the penny had dropped and even someone as dim as your author realised that our well-travelled mystery family of photographers were holidaying on the Norfolk Broads.

Nestled towards the southern end of England’s east coast, the Norfolk Broads cover over 100 square miles of flat formerly marshy land comprising 120 miles of navigable waterways interspersed by lakes, or broads, thought to have formed as ancient peat workings flooded. Most of the 63 broads, scattered between seven rivers, are less than 13 ft deep hence the need for shallow drafted wherries to navigate on and between them.

At first, I assumed it would be easy to identify the drainage pump. Although, like locomotives and boats, they all look the same just how many windmills can there be on the Broads? As an inhabitant of the other end of the county – all hills, rain, steep drops and watermills, I assumed they’d be few in number and easy to locate.

In 1972, up here in the Debatable Lands, Mr J E Hughes published an article through the Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian Society. His exhaustive research discovered seven windmills visibly remaining in my own county, twenty-five vanished and another five likely to have existed given the evidence of placenames.

Even without the advantage of such things as flooding mines, our cousins down there in Norfolk prove us to be hapless amateurs. They might not have food on the shelves or petrol in their tanks but they possess plenty of windmills. Those of us who get a nose bleed south of Penrith and suffer vertigo close to sea level might be surprised to hear that Wikipedia’s Drainage Mills in Norfolk lists over one hundred and twenty such structures.

Having consulted it, I still wasn’t sure where our mystery windmill water pump was. While getting busy on Google Maps and Street View, I noted the structure to be thin compared to much of the competition and boasting a window halfway between the door and the start of the bit that holds the sails. Having said that, the photograph is about one hundred years old. The mill may now be altered, converted, or demolished altogether.

All I could say with certainty, given the content of later photographs, is that it probably sat on the River Bure southeast of St Benet’s Abbey and northwest of our mystery maltings. Then again, it might not.

Mr Jonathan Neville of the excellent Norfolk Mills website came to the rescue. Turns out Wikipedia are amateurs too. Mr Neville’s website contains details of an astonishing 1,200 mills illustrated by over 3,000 photographs. He identified our mystery mill as being the Stracey Arms drainage pump at Tunstall, built in the 1880s for Sir Henry Stacey of Rackheath Hall to drain neighbouring marshland into the River Bure. I deffer to Norfolk Mill’s authoritative text,

The now slightly leaning 4 storey red brick tower had a Norfolk boat shaped cap with a petticoat. Power to the internal turbine pump that replaced the original scoop wheel, was supplied by four patent sails via a cast iron upright shaft and the cap was turned to wind by a white & red striped 8 bladed fantail with a Y wheel and a tailpole. When built, the tower rested on 40ft wooden piles and a pitch pine raft. In the mills earlier days it was known as Arnup’s Mill. Mill is Grade ll listed.

Last used for its original purpose in the 1940s, during the Second World War the tower was converted to a pillbox and covered with gun ports. Subsequently taken over by the Windmills Trust and restored, water pumping continues on the site but is controlled by an electric pump in a neighbouring brick shed.

The album’s first layman-friendly recognisable landmark shows the distinctive outline of St Benet’s Abbey. The eye-catching building isn’t the actual abbey, which lies as a ground-level ruin some 350 yards to the east, but a gatehouse with the conical building inside it being a subsequently constructed mill.

Puffins will be pleased to read it was King Cnut of Denmark and England who granted the land to Benedictine hermits in the 11th century. Setting aside a 1920s camera lens, imagination must be employed.

Arial photography shows a large area of land encircled equally by river and moat. Within the confines, besides the abbey chapel, we must assume the presence of dwellings, a chapter house, gardens, enclosures for animals, perhaps trees and fruit bushes, definitely buildings and moorings next to the Bure.

The Norfolk Archeological Trust describes a rich history. The peasant’s revolt interrupted any tranquillity. Sir John Oldcastle, the inspiration for Shakespeare’s Falstaff, is said to be buried at the site. Upon dissolution, Henry the VIII seized all of the monasteries in England, except St Benet’s which continued under an abbot until running out of money anyway and became derelict. In 1987 the Queen erected a crucifix of Sandringham oak at the site of the abbey knave. It is decorated with a simple one-word inscription, “Peace”.

Opposite St Benet’s, a cul de sac of the River Bure heads southwesterly to South Walsham Broad. Tying up at what is now the Fairhaven Woodland and Water Garden allows a pleasant walk to Lord Fairhaven’s Hall behind which sit the twin parish churches of St Lawrence and St Mary.

During the Second World War, the hall was a base for the Home Guard and a convalescent home. Tanks sat in the gardens, wherries covered in barbed wire lay across the broad to deter Nazi flying boats.

Sharing the same graveyard, in the modern-day St Marys and St Lawrences also only have one tower between the pair of them. St Marys dates from the 13th century and is still used for worship, albeit as part of five combined parishes presently vacant of a vicar. St Lawrence’s has been an arts and training centre since 2002.

As for St Lawerence’s tower, it is photographed its post-1827 incarnation having been damaged by fire in that year. In March 1971, what remained collapsed after being struck by lightning.

The first Lord Fairhaven was Lieutenant Urban Huttleston Broughton. Born in Fairhaven, Massachusetts in 1896, Urban’s mother was one of the Massecuccetts Huttleston Rogers who made their money in oil. His father was an English sewerage engineer who, upon returning to England, became Conservative MP for Preston. In 1946 the Fairhaven’s bought the wartime dilapidated manor house and restored it.

We shall tie up at Lord Fairhaven’s mooring. As the gentlemen enjoy the sun setting over South Walsham Broad, with its reeds and family of swans, the ladies will lash the decks with canvas for the night.

Next time, we will take a look at the passengers, one of whom, Greta Thunberg and Vladimir Putin style, turned out to be an immortal celebrity (well known to Puffins) captured on film.

Acknowledgements

Jonathan Neville, Norfolk Mills Website – highly recommended to Puffins.

Norfolk Architectural Trust

Wiki

© 2021 Photographs and text Always Worth Saying

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file

Audio Player