December 1st, 1810.

We have crossed the Equator again, in the opposite direction. Our polar bears Boris and Beaivi must be the first of their kind to have ventured into the Southern Hemisphere, if only for a few days, but they miss the comforting coolness of the northern snows. Never mind, we are on our way home.

December 11th, 1810.

We are in Colombo, the principal city of Ceylon, situated a little way up the west coast so that we had to sail around the shore to reach it. Facing the mainland of India, the city is a stronghold of the East India Company. It is of the kind that we have learnt to expect in these parts, with a central administrative district built in a more or less European manner, which quickly fades into the native style as you leave the centre.

Knowing nothing of the local tongue, we engaged the services of a guide, Asiri, who spoke reasonable English. From him we learned that the Company controls a substantial portion of the coastline while the interior remains under the rule of the King of Kandy, Sri Vikrama Rajasinha. I suspect that his sway will not last more than a few years as the Company encroaches on his territory. Well, better their reasonably benevolent rule than the ramshackle tyranny of the French.

I was intrigued to find that the words in the local Sinhalese language for the first new numbers are eka, deka, tuna, hatara, paha, haya, hata. We are back in our own world again: compare the Greek words εἷς, δύο, τρείς, τέσσαρα, πέντε, ἕξ, ἑπτά. These people may be the most easterly outposts of the descendants of the ancient forerunners of both Europeans and the western Asiatic races. Such an idea was first expressed by Sir William Jones a few years ago, inspired by his studies of Greek, Latin and Sanskrit, but it is a surprise to find it supported in such a far-flung location.

Most of the population follow the religion of Buddha, which seems to keep them honest and respectable though I have my doubts about the moral value of its pursuit of spiritual perfection. In the words of our Lord as reported by St Mark, Ὃς γὰρ ἃν θέλῃ τὴν ψυχὴν αὐτοῦ σῶσαι, ἀπολέσει αὐτήν – which our English Bible translates as ‘For whosoever will save his life shall lose it’, but the word ψυχή might better be translated as ‘soul’. Better to forget oneself and care for others.

These thoughts aside, they are a handsome and agreeable people, and relations between them and the Company men remain harmonious. Asiri says that the King is ill disposed to the settlers, as is only reasonable since they are gnawing at the edges of his kingdom. There has already been armed conflict between the two parties, and the city of Kandy, at the centre of the island, has been briefly occupied by a British military expedition. The King himself is said to be in the hands of a corrupt cabal of advisers whose only intention is to gain advantage from the present situation.

December 14th, 1810.

The island is an important producer of cinnamon. Count Bagarov is now alert to the possibility of financial profit from an expedition that he launched as a voyage of exploration, but I think that he is finding that even his considerable wealth is strained by the support of a ship constantly requiring repairs and stores, not to mention a hungry crew of bears and men. He is therefore purchasing a good stock of this spice.

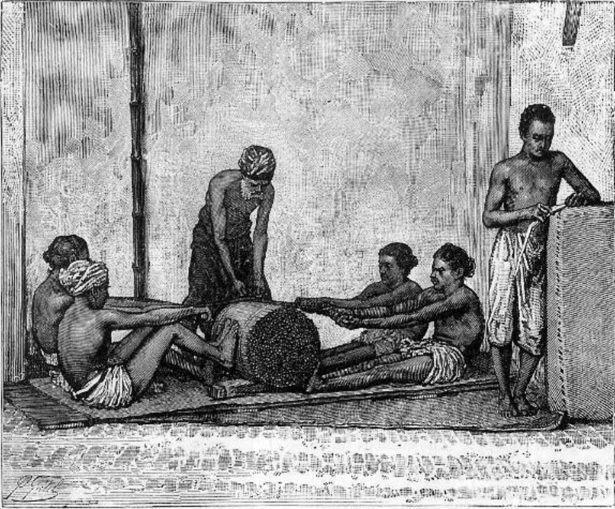

The preparation of cinnamon is curious. The spice consists of the inner bark of a tree, which is stripped off and rolled into cylinders the size of a woman’s little finger before being dried. These cylinders are bound together into a larger one, an operation requiring both strength and skill. The result is a bundle resembling a drum, which can conveniently be stowed in a barrel for shipment abroad.

The Dronning Bengjerd, already redolent of nutmeg, cloves and cardamom, now smells overpoweringly of cinnamon. Seldom has there been a more fragrant ship. One scarcely notices the underlying reek of her occupants and their daily activities.

The food that we sample from stalls in the city is usually flavoured with the chilli fruit, a small red pod which gives it a taste that is often searingly fiery. Curiously, the plant is of central American origin and has only spread to these parts in recent years. At first we found the flavour daunting, but the palate soon adapts to its tickle and we now find food without chillies a little insipid. The Count has also bought a good store of dried chilli pods to take back to Russia, though he professes himself uncertain as to whether the people will take to it. In my view it might be more successful in England, much of whose staple food is so tasteless that the inhabitants feel the need to enliven it with pungent condiments made of mustard, pepper, ginger, anchovies and other strong-flavoured ingredients. When I think of the dismal fare I have consumed in English inns, it seems to me that an establishment offering the vividly flavoured dishes of Asia would be a roaring success.

December 16th, 1810.

I am astonished to say that we have encountered some more dancing bears, something hardly to be expected in an island so far from their natural haunts. Having sufficiently sampled the delights of Colombo – and, it has to be said, its noise and stink – we were engaged in a ramble in the surrounding countryside.

We had stopped to admire a dagoba – a large stone structure resembling a bell that serves as a shrine for a relic of a Buddhist saint – when we heard the beating of a small drum and the snarl of a shawm. The sound came from a nearby village, to which we hurried to find the cause of the celebration. Here we found two men gaily capering with two tiny bears scarcely taller, when standing on their hind legs, than the men themselves. Not wishing to cause a diversion, we watched the performance from a distance, but judged it an adroit one. We also noticed that the bears were not chained and seemed to be dancing willingly with their human companions, a sight that gladdened our hearts.

When the dance was finished and the men were passing round baskets for contributions from the spectators, we introduced ourselves to the amazement of all present. We learned through the translation of Asiri that bears and men alike came from the mountainous north of India, and had wandered around the vast peninsula and the isle of Ceylon much as I had travelled with Fred in our performing days. The bears were a couple named Rajah and Rani – ‘king’ and ‘queen’ in the Hindustani language – and the two men were called Sasthi and Amul.

They were awed by the size of the bears in our party, especially the two polar bears who were at least twice as tall as the royal couple. We had, of course, told them that we were skilled in the dance, and a performance was requested. Luckily Jem always has his flute in his pocket, and we performed before them and the villagers in a style astounded them. Our rendition of the Russian gopak left all speechless.

I wish I could have joined in that dance, but sadly I must admit that such feats are now beyond me. When I was in the library at Trinity in a gentle time that seems an age ago, I found in a dusty box a tattered ancient manuscript believed to be a late poem by Sappho, no longer a lusty young lass but an ageing woman recalling her youth. It contained the lines

Βάρυς δὲ μ’ ὀ θῦμος πεπόηται, γόνα δ’ οὐ φέροισι,

τὰ δὴ πότα λαίψηρ’ ἔον ὄρχησθ’ ἴσα νεβρίοισι.

My heart is heavy in my breast,

My knees are stiff and sore.

Once I could dance like a young fawn;

Such times will come no more.

Now more than ever I feel her regret. But I hasten to add that the apparent rhyme in the two lines of the original Greek is merely an accident. Rhyme had not been invented in Sappho’s time, and the coincidence of endings would have passed unnoticed or actually have been condemned. When no less a person than Cicero wrote the pentameter line O fortunatam natam, me consule Romam – ‘O fortunate Rome, born when I was consul’ – Juvenal ridiculed it for its cacophony as much as its presumption.

We forbore to solicit contributions: the villagers had already given what they could to support their Indian visitors. While we were conversing amicably, if slowly, through the medium of Asiri, we heard strange cries and the noise of a commotion from the other side of the village, and all hastened to find the cause of the disturbance. And it was a considerable one, for an elephant employed by one of the villagers to carry felled trees had fallen into a steep-sided drainage ditch and, although uninjured, could not get out. He was trumpeting piteously, the sound that had we had heard from a distance.

Rescue was a task that could clearly be accomplished only by a party of bears. But when we looked over the edge of the ditch, the poor creature was struck with panic and redoubled his cries. The owner told us that his elephant was particularly partial to a vegetable resembling kale, of which he had a stock. I took some under my arm and, at a reassuring distance from the elephant, climbed down the bank, and slowly and confidingly approached him, holding out my offering. To my relief, he accepted it.

It was time now for all the bears – and there were now a dozen of us! – to make our peace with the elephant and engage ourselves in the considerable task of raising him from the ditch. When he had recovered sufficiently from our approach and seen that we offered no threat, we conducted him to a part of the ditch where the sides sloped at a shallower angle. We had no proper way of communicating with this exotic beast, but for the time being gestures sufficed. Then we bundled him around to face up the steep slope, arranged ourselves around his massive grey hindquarters, and pushed with all our might.

As the elephant struggled up the first few feet of the slope we stood at the bottom of the ditch and had no difficulty in propelling him. Yet we had to raise him a good twenty feet, and the farther we went the less foothold we had. The huge Boris and Beaivi remained at the bottom, supporting us while we dug our feet into the ground and heaved two tons of elephant aloft. And we succeeded: at last the creature clambered up the last few feet of the incline and stood blinking while his owner embraced him and the villagers cheered.

The elephant is called Ranga, and his human Gihan. Overwhelmingly effusive congratulations were offered by all, and there were calls for a feast to celebrate the occasion. We were happy to join with them, but realised that the slim resources of a village would be entirely dispersed by accommodating the vast appetites of a party of bears, something that has strained even the ample resources of the Count on our voyage. Accordingly, he, Fred and Jem went off to the local market to purchase what food and drink they could find, while we bears repaired to the nearby river with Asiri to catch as many fish as possible.

Aided by the local knowledge of Asiri and the skilled paws of Boris and Beaivi, in a couple of hours we had a good haul, and returned to the village to find preparations well under way. And what a night we had! All difficulties with language vanished in the joy of the moment. Replete with fish and rice, and animated with a local spirit distilled from coconut juice and called arak, we danced with Ranga the elephant far into the night, and finally collapsed on the warm ground in a happy heap.

Copyright © Tachybaptus 2019

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file

Audio Player