October 12th, 1810 (September 30th O.S.).

We sail on, occupied by many small repairs necessary after the storm. Damaged blocks have to be replaced, and lashings that have worked loose need remaking. Yet all in all our sturdy old tub has stood up well to its ordeal.

So has Dolores, who is now up and walking painfully about on the heaving deck. I now understand why Euripides’ Medea says:

Λέγουσι δ’ ἡμᾶς ὡς ἀκίνδυνον βίον

ζῶμεν κατ’ οἴκους, οἱ δὲ μάρνανται δορί,

κακῶς φρονοῦντες· ὡς τρὶς ἂν παρ’ ἀσπίδα

στῆναι θέλοιμ’ ἂν μᾶλλον ἢ τεκεῖν ἅπαξ.

Men say we live a carefree life at home

Out of harm’s way, while they fight with the spear.

How wrong! – for I would rather stand three times

In battle with my shield, than once give birth.

But little Aeolus is a delight, and all the female bears are clamouring for a chance to hold him.

We are headed for Canton in China, where there are large shipyards and we can equip ourselves for the voyage home. There are also a fair number of Jews, which will allow Count Bagarov to avail himself of their unique and valuable service. If you possess a fair fortune and a good reputation you may borrow money from any Jewish man of business in the farthest corner of the world, and pay the money back later, with a not unreasonable commission, to another Jew in an equally remote location such as Archangel, and somehow the transaction will be communicated across the world, though it may travel at the pace of an ambling horse. The system depends on the honour of all parties involved, which may not be inviolate; but despite the occasional abuse it has stood for many years and is an indispensable boon to voyagers such as ourselves.

October 20th, 1810.

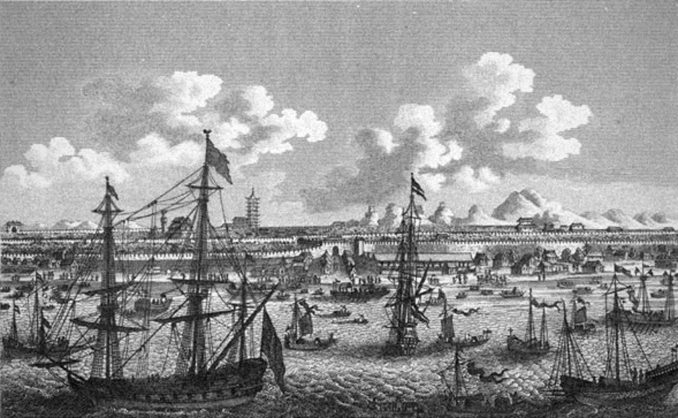

We are in Canton, whose sheltered harbour is reached by sailing up the broad estuary of the Pearl River. Far as it is from home, I feel that we are back in the familiar world, and here it is unequivocally October the 20th and from now on I shall abandon the Old Style dates, as the crew and even the Count have been obliged to do. They can lose their twelve days’ difference when they are safely back in Russia.

This is a port city, not unlike others of its kind such as Bristol, except that it is inhabited by Chinese. Folk are much the same the world over, and perhaps the main difference is that the food is much better. The streets are full of little stalls where the most delicious little things are dispensed for a few pence, and we bears have been indulging ourselves mightily. In a city where foreign visitors abound language may be dispensed with, and signs will secure us everything we need – perhaps at an inflated price for outsiders, but still a bargain. I have never felt less hampered by my lack of human speech.

The sailors too have been availing themselves of the local delights. Their principal goal has been what are euphemistically named ‘flower boats’, which are – to put it indelicately – floating bordellos. Those in Canton itself are reserved for the Chinese, but only a short distance to the east in Whampoa there are similar boats which offer the same services in a less delicate form for foreigners. Should anyone contract an infection, a Chinese barber will cure it with oriental herbs with an ease and speed unthinkable in England, where they poison you with mercury until you are half dead in the hope that the illness will be three quarters killed, but it always returns.

Our good ship the Dronning Bengjerd too is in need of what services the port can provide. Her seams have been strained by her being first trapped in ice and then battered by a storm, and she is leaking sadly – latterly we have had to spend a good two hours a day pumping her out. While she is in dock being recaulked, we shall have the extra layer of wooden armour removed from the bow, as it has been much mangled by butting through the ice and in these waters is now no more than impediment to sailing. We have carried the removed copper sheathing with us in the ballast, and this shall be replaced to serve its purpose in excluding the shipworm that bores into the hull.

To negotiate this work we have enlisted the services of a Chinese agent named Rongwei, who speaks both Russian and English with some fluency. He has secured us a contract at a fraction of the price we would pay in a western dockyard, and the task is being carried forward with remarkable speed. Rongwei said that, should we wish to abandon our cumbersome European ship and purchase a serviceable Chinese junk, he could arrange for one of any desired size to be constructed for us in a few weeks.

To drive home his point, he took us on a little voyage down the estuary in a junk, and we were all surprised at how handy the ungainly vessel was, and how well its peculiar sails made of matting strengthened by bamboo slats functioned even when sailing close to the wind. The Count praised the junk but gracefully declined the offer, saying that it was best to stick to what he was used to. Rongwei took this in good part, and in fact I think his real object had been to demonstrate to us the superiority of his nation over a band of foreign barbarians, however good their money.

November 1st, 1810.

This morning we brought our ship out of the dock, fully repaired and watertight and as good as ever she was. Our provisions are fully restocked, and we are ready to set a course for the East Indies. Men and bears have reported for duty – but where is Bruin? No one has seen him since yesterday afternoon. My mother’s heart is racked with anxiety. We have been quartering the city in an effort to pick up his scent, without result so far. The search continues into the night, and I write this in haste before going out again.

November 2nd, 1810.

After an interminable night, at dawn Emily came galloping down to the quayside. Her sensitive nose had detected Bruin in a house on the northern outskirts of the city. She reported that it was surrounded by a walled courtyard and difficult of access. As the other bears straggled in to report, the Count, Fred, Jem and myself were drawing up a plan.

We agreed that, in a foreign city, we could have no recourse to the authorities who would take the part of the residents, however heinous their actions. There was no alternative to a direct assault on the building, after which we would have to leave hastily to escape the consequences.

We enlisted the aid of Rongwei to hire two carts drawn by mules. Though he was aware of our plan to assault the people of his city, he was perfectly willing to aid us if well paid, for which he earned our heartfelt thanks. He explained that Bruin had probably been taken so that he could be killed and his organs used in preparing Chinese medicine – at which my heart froze, and from that moment on I could think of nothing except the coming attack.

Looking back more calmly on this moment, I can see that Chinese medicine, so beneficial in its use of herbs to cure sailors of a dose of the clap, has a superstitious and malignant side where useless nostrums cruelly obtained are sold at high prices in a vain attempt to shore up the fading virility of old men who should long ago have laid their lusts to rest.

On one of the carts we placed one of our two three-pounder deck cannon, a cumbersome thing but easily lifted by a couple of bears. The other was loaded with powder and ball for this weapon, with all the ship’s axes kept for cutting away fallen rigging, and several large sledgehammers. Those of us who had them from the Spanish war carried our sabres in sheaths on shoulder straps. The Count, Fred and Jem, and a selected party of a dozen sailors, were armed with muskets, pistols, cutlasses and daggers. Thus accoutred, we set out through the streets in a fearsome procession that made bystanders creep into the shadows.

At the house, there was no doubt that Emily’s acute senses had led us to the right place. We could all scent Bruin, and that he was in some distress. Yet we dared not call to him, for we needed the element of surprise on our side.

The house was behind a blank wall with a heavy gate. We set down our cannon, loaded and primed it, and trained it on the lock. One well-aimed ball smashed it to atoms, and before the smoke had cleared we were through and charging into the house, roaring with bloody fury. There was an answering call from the upper storey.

In a moment we were in the house. Most of the people fled for their lives, but the few who tried to resist were dealt with mercilessly. If a person’s head has been torn from his shoulders, he can hardly complain to the authorities about his treatment.

Moments later we were at the top of the house smashing open the door of the room where Bruin was confined. He was in chains but – O! how my heart surged in relief – completely uninjured. A few axe blows and he was free. We descended the stairs like a thunderbolt and milled out into the courtyard.

A moment to heave the cannon back on to the cart – you never know when you might need to blow something to pieces – and we were off, leaving behind us a scene of devastation from which it would take a while for the survivors to stagger out and raise the alarm. We surged down the hill and made for the harbour as fast as the mules could canter when pursued by bears.

Master Ulyanov had brought the ship right up to the quayside, so there was no call for boats. He had also rigged a hoist for the heavier items. We swung the cannon aboard, followed by the unused ammunition and arms in a sling, then swarmed up the gangplank. It was the work of a few minutes to set sail, and then we were heading briskly down the Pearl River estuary, far ahead of any possible pursuit.

Bruin said that he had been at a market stall buying food when an unknown man had offered him one of his favourite titbits, a steamed bun filled with roasted pork. He could recall no more until he had woken up chained and confined. Evidently the treat had been infused with some soporific drug, of which no doubt the ingenious Chinese have an ample store.

I did not tell him of the fate he had escaped. My dear Bruin has endured a dreadful experience and I will not augment it with tales of horror. I enjoined bears and men to silence on this dismal subject.

November 4th, 1810.

We are bowling along on a south-south-easterly course with a brisk following breeze, bound for our next landfall in Batavia in the Dutch East Indies, where we hope for a more hospitable welcome. Yet let us not forget Juvenal’s warning:

Omnibus in terris, quae sunt a Gadibus usque

Auroram et Gangen, pauci dinoscere possunt

Vera bona atque illis multum diversa, remota

Erroris nebula.

In all the lands from Cádiz to the east

And the far Ganges, very few are able

To tell true good from many different things

Or lift the cloud of error.

At least the Chinese shipyard has done fine work on the Dronning Bengjerd. The removal of the armour at the bow has made the ship a little swifter and more easy to handle, though it has not reduced her ponderous rolling in all but the lightest seas – but we are so accustomed to this that we barely notice it.

Dolores and little Aeolus continue to prosper, and are idolised by the crew, men and bears alike. Though it is said that it is unlucky to have a woman aboard, to have a birth is considered the height of good fortune. Let us hope that these simple beliefs are justified.

Copyright © Tachybaptus 2019

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file