March 29th, 1810 (March 17th O.S.).

We have good news brought by one of the Count’s agents returning from St Petersburg. A suitable ship has been found and purchased, and is now on her long way around the Norwegian coast to Archangel. She is the Danish ship Dronning Bengjerd, named after the medieval Queen Berengaria, the Portuguese-born consort of the Danish King Valdemar II in the 13th century. I hope that the Portuguese name, though mangled by northern tongues, is a good omen for us after our military success in that country.

April 5th, 1810 (March 24th O.S.).

Our ship has arrived in Archangel harbour, and we have gone out to her to inspect the Count’s new acquisition. The word ‘ship’ is perhaps too elegant to describe this dumpy little vessel of 325 tons displacement, whose lines recall a bathtub more than a majestic man of war. But there is no doubt that she is very strongly built, and will serve our purpose well enough,

The master of the ship on her voyage, Ilya Ulyanov, told us that she sails ‘like a pig’, rolling heavily, responding sluggishly to the helm, and sagging badly downwind. No matter: we are not buying a racing yacht.

To our surprise, she arrived fully armed with two 10-inch mortars and 12 guns of various sizes, and with a reasonable supply of powder, mortar bombs and cannonballs for all of them. We shall keep all these things on our voyage. The bombs may prove useful if we need to blast a passage through the ice.

April 7th, 1810 (March 26th O.S.).

The Dronning Bengjerd is now in dock, being strengthened for her voyage. Extra frames are being inserted at the fore end, and on the outside the copper sheathing at the bow (whose purpose is to resist the Teredo shipworm, which eats its way into the wood) is being removed to make way for an extra layer of oaken strakes. The forward edge of the bow will be armed with iron plates, protecting the hull from abrasion when butting through pack ice. The copper will not be replaced here, as it would only be torn off. Also, it has been observed that when copper and iron are placed close together in sea water the iron is quickly eaten away – something that might be explained by our friend Sir Humphry Davy, were he present.

We are also laying in supplies for what may prove a long voyage. I am concerned about the likelihood of scurvy among the sailors when we are to spend months living on ship’s rations. It has certainly killed more sailors than the enemy’s guns ever did. When I was at Cambridge I read James Lind’s book A Treatise of the Scurvy, whose author describes how, having made experiments on groups of sailors, he discovered that eating fresh fruit, particularly lemons and oranges, protected them from the disease. That is not a luxury we can offer them in the frozen north.

However, Captain James Cook kept his sailors healthy on his long voyage by making them eat the smelly German fermented cabbage called Sauerkraut, and this is readily available so we have ordered a plentiful store of barrels. Cook found his men unwilling to eat the stuff and one can hardly blame them, but administering a dose before the rum ration should have the desired effect.

Another antiscorbutic method which has been proved effective is to eat freshly sprouted leaves. Even on a ship in the Arctic it is possible to germinate cress seeds on blankets moistened with fresh water, though it is hard to produce enough for a ship’s crew. I have read that the Chinese did the same on long voyages with ginger plants, but we have no ginger root here and do not know how to grow it anyway.

We bears do not suffer from scurvy.

April 17th, 1810 (April 10th O.S.)

This is Easter Sunday in the Old Style calendar, though the vagaries of the system for determining the date of Easter decreed by the Council of Nicaea in A.D. 325 cause us in England to celebrate it on the following Sunday. We have attended all the services for the three days in the Count’s chapel, and now people are greeting each other with joyful shouts of ‘Khristos voskres’, ‘Christ is risen.’ We have had a grand feast of kulich, a kind of sweet bread; paskha, which literally means Easter but here refers to a dish made of cottage cheese, raisins and nuts; and of course eggs, dyed red by boiling them wrapped in onion skin.

We cannot continue to celebrate festivals twice. When Christ is risen, He is risen and, in the words of Dr Johnson, ‘there’s an end on ’t.’

May 12th, 1810 (April 30th O.S.).

Work is finished on the ship, and our stores are being loaded. Thanks to the good Count, our expedition is provisioned for every eventuality. We shall be in known waters until we reach Spitsbergen, but the territory beyond that is largely unexplored, and we are carrying a store of the traditional gifts to secure the good will of any natives we may encounter: knives, mirrors and glass beads.

We also expect our voyage to be a slow one, and are setting out well in advance of the least annual extent of sea ice, which occurs in early autumn. We should be able to reach Spitsbergen without undue obstruction, and will then wait for the first opportunity to depart. It is better to be too early than too late. However, as Homer says, Ἀλλ’ ἤτοι μὲν ταῦτα θεῶν ἐν γούνασι κεῖται, But truly these things rest on the knees of the gods.

Of the ship’s original crew of thirty-two, twenty men including Master Ulyanov have declared themselves willing to take part in our voyage. The more faint-hearted will be able to find themselves berths on ships leaving Archangel for more southerly destinations, and we do not need such timid folk on what may prove an arduous expedition. Ten bears, Fred, Jem, Dolores and the indomitable Count will more than make up the deficiency. The Count is also bringing one manservant, Dmitri, to attend to his personal needs; he is a good enough fellow but we cannot know how well he will fare in the ice.

It is curious that our host, blessed with a considerable fortune and good looks and in the prime of life, has not seen fit to marry. Perhaps he is too set in his enthusiasm for exploration to trouble himself with affairs of the heart, or perhaps his tastes lie elsewhere. It is not for me to enquire.

May 14th, 1810 (May 2nd O.S.).

We are under way. Yesterday, which was a Sunday, we attended a service of blessing for our voyage, and may it stand us in good stead for the difficulties to come. Our spirits are high and we have good hopes of success but, to quote Homer again, Ἀλλ’ οὐ Ζεὺς ἄνδρεσσι νοήματα πάντα τελευτᾷ, Yet Zeus does not fulfil all the designs of men.

As Ulyanov warned us, the ship is a fat wallowing tub, slow and unmanageable, and the strengthening work has no doubt made her worse. Even with a brisk wind she struggles to make six knots, and tacking into a headwind is a sad crawl. However, we are not in a hurry, and no doubt the stout hull will prove an advantage when we are in the ice.

Our polar bears have never been on a ship before, but are already enjoying climbing up the rigging. We are showing them the ropes – literally – and teaching them the skills and duties of sailors.

Dmitri is painfully seasick in little more than a flat calm.

May 17th, 1810 (May 5th O.S.).

We passed south of Kolguyev Island, a place that has not been fully surveyed. There is no reason to stop here, for it is uninhabited apart from temporary encampments of seal hunters.

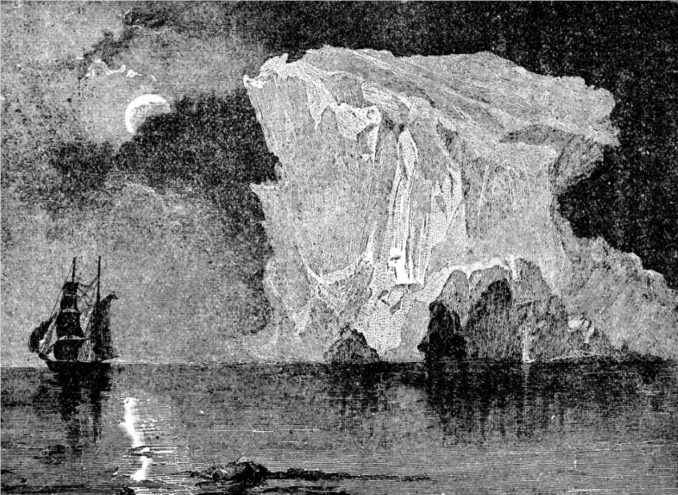

That evening we had our first sight of an iceberg, a lofty and gleaming tower made all the more majestic by the gathering dusk. As every schoolboy knows, nine-tenths of an iceberg is under water, and the submerged portion extends for some way below the surface, so one must keep well clear of every one lest the ship be torn open by an unseen icy projection.

May 19th, 1810 (May 7th O.S.).

We have had our first encounter with pack ice, frozen out of the sea last winter and still only partly melted. So far it is not very thick, either in terms of the proportion of open water it occupies or as regards its depth from top to bottom, only a couple of feet in the main.

We keep a lookout constantly in the foretop, who scans the sea ahead for open passages running as nearly as possible in our desired direction, and thus we thread our way in a zigzag course. Occasionally it is necessary to butt our way through obstacles, and the hull resounds with heavy thumps and hideous screeches. At these times we are grateful for the Count’s foresight in strengthening the hull and adding armour to the bow.

We can only make progress in the daytime when we can see clearly. During the nights, already very short in these northern latitudes, we moor the ship to a large ice floe. We have been out to explore one of these, but it was without the faintest trace of a living creature.

May 22nd, 1810 (May 10th O.S.).

We sighted Novaya Zemlya yesterday afternoon. Sailing up the west coast we encountered a Norwegian whaling ship, the Hvalross, which means ‘walrus’. The Count, Ulyanov, Fred, Jem and myself went across in a boat to confer with the captain. When he had recovered from the shock of seeing a bear coming over the side we had a conversation in a mixture of bad Russian and worse German. He told us that the ice to the east is still thick, and we should wait for a while before penetrating it. He advised us to put in at an inlet a short way to the north, where there is a settlement of Pomor seal hunters.

The Pomors are Russians, principally from Novgorod, who have sailed around and inhabited this region for some centuries – the name Pomor means ‘seagoers’. They form the bulk of the very small population of these islands, along with a handful of the native Samoyed people – and even they, with their skills at living in the northern waste, find this barren land unrewarding. Nevertheless, it is claimed by the Russian crown. Well, we bears claim our territories of a few square miles, and humans do the same on a grander and thoroughly pretentious scale. Here I see nothing but an icy wilderness that belongs to no one, though further examination may reveal more.

May 23rd, 1810 (May 11th O.S.).

We found the Pomor settlement in a sheltered bay, a small collection of shacks constructed from driftwood, whale bones, rough stones and sailcloth, and have moored our ship and gone ashore. The inhabitants were awed by the arrival of a Count and frankly shocked by the presence of bears. It seems that there is a running war between the settlers and the local polar bears – hardly surprising, as humans have invaded the bears’ territory. Assured of their safety by the Count, beguiled by a hastily conducted dance, and seduced by gifts, they have accepted us as benign visitors; but things may be different elsewhere in this remote place.

May 25th, 1810 (May 13th O.S.).

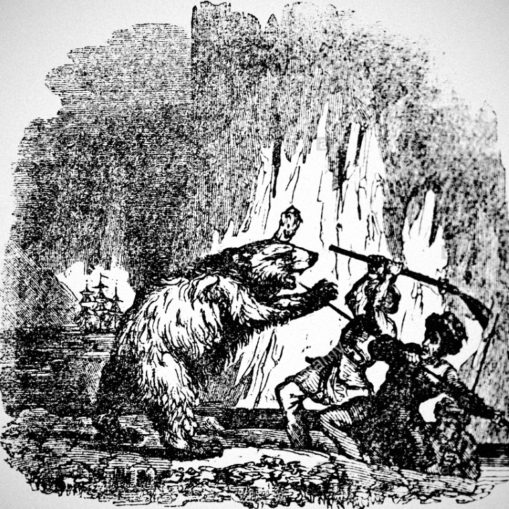

Indeed my fears expressed in the last entry were well founded. The ever curious Count, eager to explore the natural history of an unknown land, mounted an expedition to the interior, taking with him Fred and Jem, and all the bears who were eager to feel snow under their paws again.

There is not much to see: an expanse of ice and rocks, and a few seabirds straggling in from the coast; but the bears’ sensitive noses picked up traces of polar bears, whom we were eager to meet.

However, what we encountered was a dismal surprise. Our own two polar bears, Nikita and Beaivi, were leading the way when we came across a party of hunters from another settlement. They were at once fired on, not accurately but Beaivi was grazed by a bullet. At once Nikita, enraged by the wounding of his mate, rushed at them, and it was only by prompt intervention that we managed to stop him from tearing the whole party to shreds. Luckily we were able to hold down and disarm the five men without further bloodshed. The Count gave them a severe lecture about their behaviour, which they pretended to heed, before returning their weapons and sending them on their way.

We may have to remain here for some time, and must maintain good relations with the local people, such as they are. Nevertheless, we have found ourselves in the midst of a bitter and endless conflict between men and polar bears. I wish it were otherwise, but the world is as we find it. As the old proverb has it, Δεὶ φέρειν τὰ τῶν θεῶν, We must bear the things that the gods send us.

Copyright © Tachybaptus 2019

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file