Bowson along with George Edward discharged themselves from the hospital mid-morning. Some of the medical staff were quite relieved to see Andy go, but not George who had been much more co-operative and was seemingly reluctant to return to duty just yet. He was back at the office just after 1.30pm, in time to see a miserable boss returning from a Home Secretary chaired update meeting which had proved something of a fiasco. The Command head was clearly in her bad books, and she bypassed him overtly, focusing on Dager and a couple of peers. A naïve person might have thought this a sign of career benefits to come, but not Dager and his colleagues. Her normal icy composure was now only masking a submerged molten magma stream of frustration that was threatening to erupt, incinerating anyone who stood in its way. Her career, ambition for progression, was on the line.

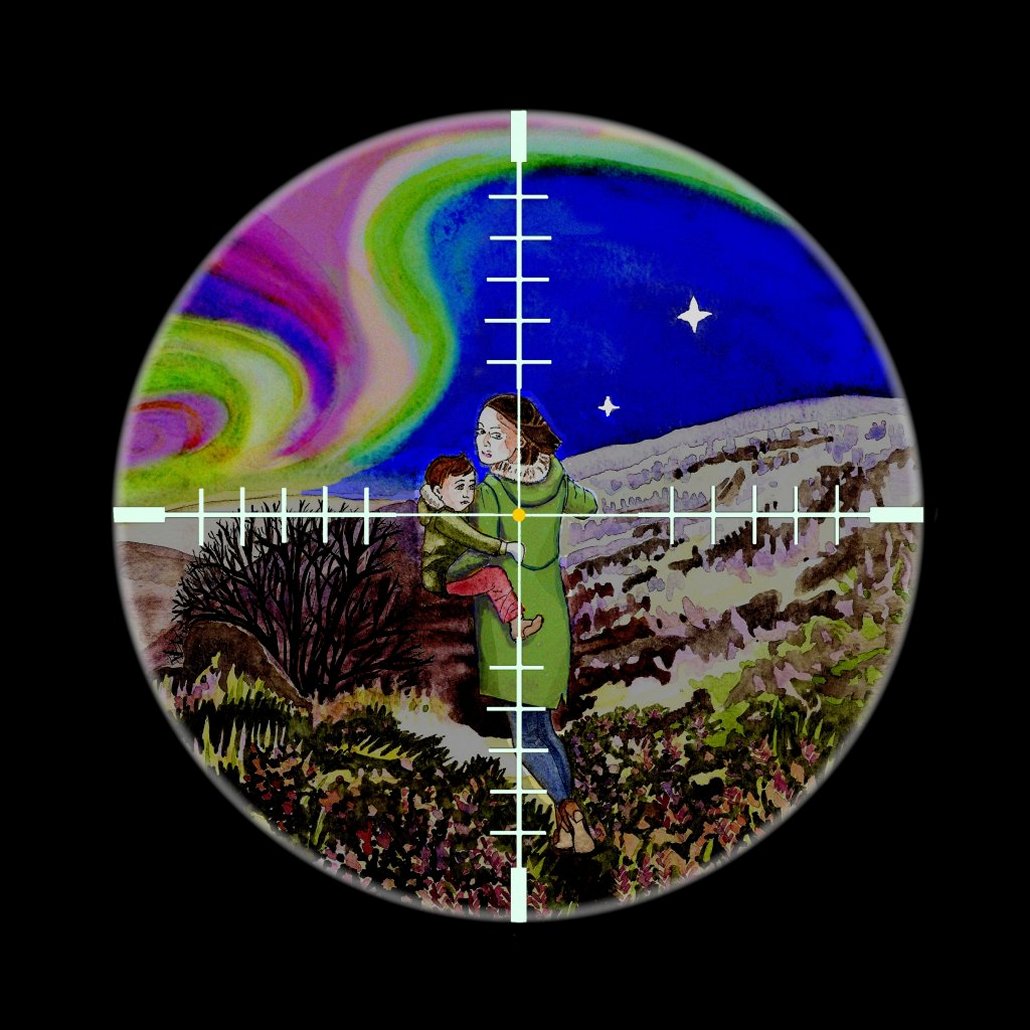

The weapons and cartridges recovered were effectively untraceable, although the FBI were now reasonably confident that the sniper rifle used to kill Amallifely was one of the batch of Barretts now believed to have been stolen, along with a terrifying inventory of other hardware, from the US Army. The few vehicles recovered were proving of little help, as were the charred remains of the house and the two recovered bodies. Trawling through witness statements, interviewing locals and family members of the suspected terrorists, had revealed little of value thus far. The posted martyr videos gave little away other than something of the subjects’ narcissistic egomania and paranoia. The only survivor remained in a medically induced coma and was undergoing a series of operations to remove bullet fragments from various vital organs. His doctors were advising this situation could continue for several more days at least.

Ted Armstrong, irritated and insulted beyond measure at his by-passing, had then commented that given the state of border controls, or almost total absence thereof, he wouldn’t be surprised if there were caches of terrorist hardware secreted all around the country along with hundreds, if not thousands, more terrorists waiting to come out of the woodwork. That kicked off a huge row, which the Home Secretary could only curtail by abandoning the meeting, swearing ‘he’s for early retirement as soon as this is over.’

‘Henry’ sat anonymously in the corner feeling much more cheerful and wondering if he should send Bowson some chocolates: on balance, probably not. Someone else present, for entirely different reasons, also left with a spring in his step.

“Mana, what have you done, that was some of our finest cloth? It’s my business too now; you can’t just give it away.”

Georgios wasn’t shouting, he knew better, but he was angry, that was clear.

“How dare you? You may be my son, my first born, but it is still my business. It will only be yours when I have passed on to join your father, perhaps a day that can’t come soon enough for you. I didn’t give it, I wanted to, but they insisted on paying, far more than my friend Iltud, my faithful helper, could afford. He’s always there to help me when I need, unlike you who go off into the outside on your adventures, indulging yourself, leaving me, your mana, and your wife and little children, all alone to struggle on, a poor widow far from home.”

Thea’s eyes were shining brightly, with excitement rather than anger Georgy could see. The few customers in the café were looking stonily at their drinks, but he knew they were smirking inside; they knew the game being played out even though they didn’t understand a word of the rapid Greek being sprayed around the little interior like machine-gun fire. The smile that was now playing across her lips, amused at her ability to pull the strings of his strong filial attachments, was there again. He couldn’t stifle the laugh, these games they had played since his teenage days; she was still that wilful teenage runaway girl in so many ways, younger, much younger, at heart than him, teasing him like an older sister would her clumsy and gauche younger brother on the subject of girls.

“Hasn’t everything I’ve ever done not been for you and yours, and for my poor loyal little Thea?” Middle-aged ‘young’ Thea, listening from the nearby kitchen giggled as usual as that stock line was wheeled out, as it must be twice daily when Georgy was about, besides his children were all well into their teens, almost of age.

He just looked at her, beaten in one move as always; she was his mana, his mum, he owed her almost everything. She held out her black sleeved arms to him; he bent down to embrace her, “Tell me again, my son, my first born, how you killed the Saracens, how hard they died…”

“Is she alright Mum?”

Sam’s anxious face awaited Martha as she returned down the stairs. They had been up several hours, it was now mid-morning but there was no sign of the girl, her bedroom door remained shut. He had finally pestered Martha into intruding on the girl’s privacy; there was no answer to her knock on the door. She opened it, the curtains remained drawn and the light dim, but enough to see a small and frightened face peeking over the pulled-up bedding covering her seated frame pressed into the corner of the small room. An uncharitable part of her thought that at least she was now only sufficiently fearful to be frightened into silence, no longer terrorised into mute catatonia. Perhaps that’s progress. She put down the tray she was carrying which held some breakfast, water and hot sweet tea, and smiled. Just those dark eyes staring at her silently, it was quite unnerving.

Time to take the bull by the horns. She opened the curtains, fresh sunlight poured in, several hours ahead of the advancing clouds. Then she opened the window, vigorous Spring air to stimulate a tired body and soul she thought. And still those eyes followed her watchfully, mournfully.

She pointed at herself, “Martha,” again “Martha,” then at the girl, “You? You?”

Still no answer, no sound, just that silent stare. Perhaps time or the priest might elicit a response. He would be round before too long with the Doctor, and there was Sam waiting anxiously like a child with a sick puppy at the vet’s, soft heart in a stone shell she thought; he’s a strange boy, things touched him unpredictably, like this child.

“She’s been through a terrible ordeal, goodness knows how terrible or for how long. Shock must be part of it; time will help with that and kindness will do the rest. Now let’s get her a bowl of warm water for bathing and hope that Iltud manages to get her some decent new clothes.”

The priest had come in with the Doctor at noon, and gone up with Martha in tow. The girl had eaten and drunk something at least, but was still there under the bedding in the corner, staring more fearfully now that there were three people in the little room with her. They all sat on the floor to appear less intimidating. Gillian opened her bag and showed it to the girl, took out a stethoscope, put it on and edged towards her: she shrank down, even smaller in the corner. Gillian backed away smiling in a resigned manner, “I can’t force her to let me check her over.”

Father Peran got on to his knees and edged forward, causing the girl to shrink back again, pressing against the walls as if trying to be absorbed into them. Then suddenly her eyes seemed to notice something for the first time, the Celtic cross hanging on his neck by a chain. “Aba? Aba?” She was pointing at him, at it, her slight voice trembling with fear and uncertainty as she looked at him anew wide-eyed. “Aba?”

Peran smiled and turned to face the others.

“She’s saying Aba, which means Father in Aramaic, the language of the Disciples. She knows I’m a priest. You said he told Sam and Alan that she was probably a Yazidi Kurd abducted from her home and then brought to this country as a slave or worse? The Yazidi, I know a little of them, they are a pagan people that have adopted bits of Christianity, Judaism and Zoroastrianism, and are treated as Devil worshippers by Muslims. They aren’t of course; at least as we would understand such a thing, they are just in grievous error. Many live in the mountains of Anatolia, often alongside Syrian Orthodox Christians, sharing the same churches, inter-marrying even, it’s quite extraordinary really. The Syria Christians still use Aramaic in their liturgy and she must have some familiarity with it. She obviously assumes I am a Christian priest from recognising my crucifix and habit. Unfortunately, that’s the limit of my Aramaic and I know no Kurdish; I fear no one else in the Pocket will be able to speak to her any more than I. Perhaps our friends from the Middle Sea will be able to help when they come, they may know more, or perhaps he can send aid in from Logres. It is in God’s, hands but He has carried her away from Babylon, of that I am certain.”

He got to his feet and took a step towards her with one hand grasping his cross. She just stared at him, poised between fear and wonder, as he made the benediction over her, stepped back and said “Aba. Aba Peran.”

Martha noticed a tear running down his cheek towards the smile he was trying to wear for her sake. As if in sympathy, tears started to flow down the girl’s cheeks, towards the faint smile of relief that framed her lips, as if to say that although she was still far from home and among strangers, at least they might be friends and she felt safe for the first time in years.

Time had slipped by, eased on by the old lady’s story-telling and they had to set off at a brisk pace to be able to catch the afternoon train back to St Leonnorus, burdened by the now heavy holdalls and even heavier bolt of cloth. Too breathless to talk on the move, the inevitable questions Iltud knew would be headed his way had to wait until they were on the train. This time he was wishing Docco would come and discourage them by his presence, but his ever unreliable brother-in-law was busy elsewhere on the little train as it headed back slowly through the fields up the valley, the clouds now coming up from the Atlantic, shrouding the blue Spring day they had been enjoying, threatening rain.

Firstly, she had wanted to know how much the cloth would be worth so one day she could repay Thea and himself. He told her probably over twenty-five times, maybe fifty times, perhaps even more, than the price she had accepted in the end; how Byzantine silks, their designs, were highly prized in the fashion and luxury markets, people thinking them made by hand in small workshops in the eastern Mediterranean, to traditional patterns. The amusing thing was much of it was bought by wealthy Arabs as bedding and wall hangings, more than clothing. He helped Thea by overseeing its transportation up to the barrier whence it was taken by ‘outside boys,’ as everyone seemed to call them, to a trusted agent who ensured they were distributed selectively to the right merchants. It was neither a big market nor a huge income earner for the Pocket, but was growing, albeit slowly given the need for absolute security.

Thea had a real head for business and was now thought to be the wealthiest woman, perhaps even the wealthiest private individual, in the land. She had achieved this largely on the back of her connections with her homeland, importing such luxury fabrics and also by a small but even more profitable side-line in importing antiquities and extremely good reproductions made with the original materials and techniques, all sold into the shadowy dealers’ markets for such things. She would only accept gold and silver coin, and some gemstones, nothing else would do in payment. She was always complaining about the commissions she had to pay middle-men and the export duties the Duchy government imposed, but had nevertheless amassed a large fortune. Who did Sally think had paid for the new Byzantine decoration of the side chapel, carried out so that she would have somewhere to remind her of home, she had said? She had had to bring over two highly skilled craftsmen from her home for two years and had donated the gold and silver in coin, the fabrics and altar dressings and even some of the icons; the remainder being a gift from her homeland’s cathedral clergy.

If she were so wealthy, Sally had asked, why did she insist on running a tiny little café with all her family involved, and not live in a large house elsewhere with servants? He had laughed at that, saying several widowers had wanted to marry her, attracted by her wealth and vibrancy, but had all been driven off, sometimes at knife point. She wanted her family to work for their living, not get lazy she said, so they knew how it had been for her. She also gave heavily to the nunnery just outside the town, helping pay for the little hospital the nuns ran, which had treated her sick and dying husband so kindly, and to other causes as well. Iltud was clearly in awe of her, finding her completely overwhelming. Would she get in trouble for spilling the beans about her homeland? He laughed in answer, the Council wouldn’t dare he confirmed, she was apparently too valuable and respected, besides they would just say it was Thea being Thea and make a joke of it, however even she knew where to draw the line.

How many “outside boys” were there, he had then been asked? Less than sixty, plus a few women called the same; she laughed at that. Only the most trusted, skilled and discreet, those who could fit seamlessly into the outside world and adopt its ways, chameleon-like and, at the same time, be resistant to culture-shock when confronted by the huge differences so close by. Some of the Pocket’s inhabitants had little interest in the outside at all; they seemingly had had their horizons circumscribed by the barrier with the outside world, although this was becoming less common since the opening of relations with the Byzantines and the advent of growing immigrant numbers from Logres.

Could some of the outside boys get a message to her husband for her, tell him she and Josey were safe, they still loved him, try to persuade him to join them? He had smiled indulgently at that: it was apparently a common request from the accidental immigrants. He was sorry they couldn’t help; it risked exposing their existence, their illicit dealings with the outside world, if they did it for her they would have to do it for others and besides would he want to come, just disappear from Logres one night never to return? Then the hammer blow of truth: anyway, he had understood she had left her husband, didn’t want to be with him anymore. There were tears at that point, so many that the emotionally reticent Iltud had had to give her a hug and ask her to forgive him his clumsiness. She pulled herself together, if only for his sake, and then the questions returned. He was keen now to talk about anything else.

What did the Byzantines want? What were they like? Had he ever met any other than Thea? Who from the Pocket had gone there?

Trade, exchange, not to be alone any more he said. Composed, dignified, almost arrogant; he had only seen a small number once or twice at official functions, but none made an effort to speak to him in his own tongue, or even English, other than Thea. Only a very few from here were permitted to travel there: it was a long and difficult trip although the Byzantines had access to modern ships, and had quietly bought into two Greek family shipping companies and could now move goods and people around much of the world undetected by the authorities. He had smiled at that, wondering what she was thinking given her initial reaction to their own small scale local smuggling.

She sat back, once more trying to digest yet another, even more seemingly fantastic revelation. What was it that Churchill had said about Russia? She wasn’t quite sure, something about it being a mystery wrapped in a riddle hidden inside an enigma or something like that; well Russia had nothing on this little place.

Then, at an intermediate stop, four well-armed and heavily laden men got on the train, sitting up the carriage from them. They had nodded perfunctorily to them, looking preoccupied and nervous, the result, Iltud whispered, of being an outside team headed into Logres on some errand or other. Their very presence inhibited her questions until the terminus, when the little carriage emptied and Docco waved them goodbye. As they set off up the lane towards the cottage she looked behind her, the four men were lounging about by the warehouse as if waiting to be met before heading off over the hills.

“What are they up to Iltud?” she had asked him.

“Just escorting trade goods out tonight most probably,” was his answer.

She didn’t ask why he wasn’t going out with them, wasn’t that part of his responsibilities, at least as far as the barrier? Later, when they had arrived back, and she had gone up to her room for a minute, she had seen four laden figures shrinking into the distance, on their own, moving up the valley hillside, no carts or pack animals in sight.

© 1642again 2018