June 12th, 1808.

I take up my pen again in London, where Jem and I have arrived after our hasty departure from Cambridge. It is quite understandable that Jem, unpaid by his lordship for more than a year, has made amends by relieving him of his silverware, and we have paid for food and lodging on our journey a spoon at a time.

At Baldock we happened on my old master Fred, who was passing through with a band of travelling performers, and I was joyfully reunited with my cub Bruin, now a seasoned dancer who varies his routines with impressions of well known public figures. His impersonation of His Royal Highness The Prince Regent had us all in stitches, and earned us £4 11s 7d when we took up a collection from the patrons of the inn where we were staying.

Fred was much taken by Jem’s notion of setting up an academy for dancing bears. ‘There’s bears and there’s bears,’ he said. ‘Now Bruin’s an artiste’ – he pronounced the word with careful respect – ‘and Daisy, in yer prime there was no one like yer. But on my travels I seen some bear acts that fair made me blub, they was so bad. Dancin’s an art and gotta be learnt proper.’

He decided to come to London with us, and of course with dear Bruin. His large acquaintance will be to our advantage in finding us pupils.

Fred also has friends in London, and after a little consultation he has found us premises in a former stable to the west of the city between the villages of Kensington and Brompton. It is at the crossing of Hell Lane and Hogmire Lane, well named thoroughfares, for it stands in a district of market gardens where fruit and vegetables are grown for sale in the metropolis. These are manured with what is politely called ‘night soil’, that is to say human excrement dredged from the city’s innumerable cesspits and transported here daily in carts. The stink is overpowering, but Jem and Fred seem not to notice. Sometimes perhaps a human’s feeble sense of smell may be to his advantage. But even Bruin and I now notice it less than when we arrived.

July 1st, 1808.

Fred has been as good as his word, and we now have no fewer than six young bears in our stable, four boys and two girls. All are comfortable on straw beds under a roof that we repaired with slates from a derelict outhouse. Jem required a deposit of £5 per head from their owners to set against the fee for the dancing course of £1 a week, not an unreasonable amount considering my reputation as a former prima ballerina of the bear world. So for the time being we have all the resources we require. However, expenses come rather high with eight bears and two humans to feed, and we are running up quite a bill with a knacker in Kensington.

With the aid of Bruin I am teaching them the gavotte, not a difficult dance. Jem provides the music on his flute, and when he is not there Fred can saw a passable tune on a fiddle.

July 10th, 1808.

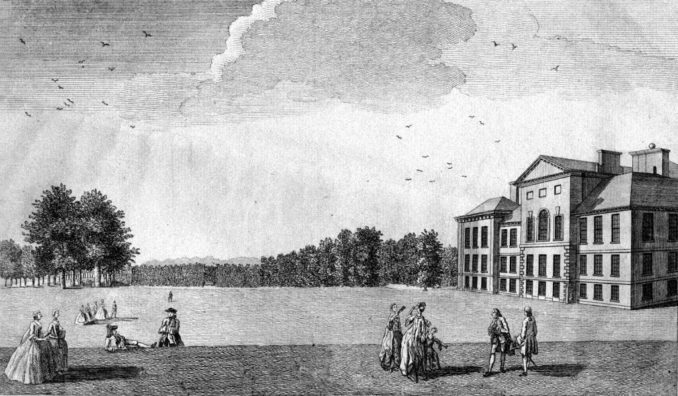

On the sunny summer days we have taken to practising our dances in Hyde Park, a short step from our premises. To reach it we walk along Kensington Gore, skirting the south edge of the private gardens of Kensington Palace. These are open to the public on Sundays, but only to well dressed persons of quality, which we are certainly not. Our dancing floor is a pleasant grove just under the ‘ha-ha’, a ditch and wall that keep common folk such as us from entering the gardens – though I and any of the bears could scale the wall in a trice.

While we were working our way through a minuet we heard voices from the other side of the obstacle. Looking over, I saw a fat, florid man, considerably overdressed. It was none other than His Royal Highness. He was accompanied by a slim, elegant, immaculately attired man, a thin grey-haired person of slightly shabby appearance, and a fine lady in an elaborate costume. All were applauding our performance.

We bowed deeply – female bears do not curtsey, an act that requires a skirt. At once a mounted equerry cantered up to bid us enter the gardens through a nearby gate, and we were introduced to the royal party. The Prince’s companions were Beau Brummell, Muzio Clementi the renowned composer and manufacturer of fine pianofortes, and the Prince’s current mistress Isabella Anne Seymour-Conway, Marchioness of Hertford. Understandably, the Marquess was nowhere to be seen; Fred told me later that he is paid to hold his tongue about being thus cuckolded.

The Prince had come to Kensington Palace for a demonstration of one of Signor Clementi’s latest instruments, with a view to acquiring one for his own music room – not that he can play a note, but he has people to do that for him. Clementi had caused several pianofortes to be transported down from his house in Kensington Church Street, which was necessary as his warehouse had burnt down a few months ago, causing him a loss of £40,000. Royal patronage will help him to rebuild his fortunes. Also, he has just secured the rights to publish the music of the famous German composer Herr Beethoven, a lucrative contract. So he can weather the near certainty that His Royal Highness will never pay for his instrument.

One of the pianofortes was brought out on to the terrace of the Orangery, where Clementi accompanied Jem’s flute to charming effect and we performed several of our dances. Then the Prince, seized by a whim, borrowed some muskets from the royal guards and we bears conducted a military drill with great aplomb until Bruin dropped one of the weapons, causing it to fire. The ball passed through Brummell’s elaborately curled coiffure, fortunately not injuring him; but he dropped down in a dead faint to the delighted laughter of the rest of the party. This brought our performance to an end.

We were entertained to a sumptuous cold collation and I consumed several bottles of hock, a delectable beverage which I had never sampled before. The other bears, not to mention Jem and Fred, were also well served and we reeled home to our stable, buoyed up by a promise of royal patronage – though we know all too well that this will never be honoured.

August 30th, 1808.

We now have as fine a troupe of dancing bears as the world has ever seen. But all is not well. The various people who brought in their young bears for training have not been paying their weekly fees, and indeed they are nowhere to be found, as they are all travelling performers constantly on the move. Our expenses are high: eight active and hungry bears will eat their way through a horse in a week, and though the horses we get from the knacker are broken-down, scrawny old creatures they still cost money, and he refuses to extend us any further credit. Add to this the expenses of the two humans and the small rent of the old stable, and we have a precarious financial prospect. Jem is down to his last few silver spoons.

Jem and Fred believe that we should ‘up sticks’ and go on tour with the troupe, a plan fraught with uncertainty as the six young bears are not legally ours. We are holding them against non-payment of fees, and a bodyguard of united bears would make it hard for the owners to reclaim them, but that is an argument that would not stand up in a court of law.

September 3rd, 1808.

Our minds have been made up for us, but not in the best of ways. One of our neighbours told us that the dreaded Bow Street Runners had been sniffing around our premises, and that he had heard a rumour that they were investigating the theft of some silver from a nobleman.

It would be prudent to leave the country for a while. The resourceful Fred has some friends in Folkestone, who are traders in brandy and other commodities best brought into England without paying the exorbitant excise duties imposed by the wretched government to support their pointless wars. He believes that he can secure us a passage to the continent in return for favours received.

We leave at dawn. I shall miss our comfortable stable and the pleasant routine of dance practice, but all good things must come to an end.

September 10th, 1808.

We have arrived in Folkestone. During our journey we gave several performances on village greens and in the yards of coaching inns, and I am glad to say that we have proved that we can make enough money to support ourselves. On our last night in Ashford, our collection took up £13 4s 2d, the most we have ever earned.

But the law will pursue us, and we need to find a ship. The local advice is that it would be foolhardy to travel to France or Spain, though smugglers’ vessels would readily carry us to either, and that the best choice is Portugal. A British force has recently landed here under the command of Lieutenant-General Sir Arthur Wellesley, a rising young officer who has already secured some early success in this campaign.

September 12th, 1808.

We are at sea, in a perfectly legitimate English merchant vessel, the Buzzard, bound for Lisbon loaded with gunpowder and cannonballs. Despite the vital importance of the cargo, most of her crew had just been seized by the press gang, and the master, one Roger Boyes, was happy to take all of us, bears and men, as able seamen for the voyage. We bears can climb the rigging with the best of them, and I have been teaching the cubs how to tie a reef knot and a bowline.

We have also been practising the hornpipe, to the delight of the sailors. The diet of salt beef boiled to rags in sea water and accompanied by weevilly ship’s biscuit is disgusting, but we only have to endure it for a few days. Jem points out that in a war there are always plenty of dead horses, and we are looking forward to them.

I am glad to be on the move again, though it may be to a Europe in the last stages of disorder. There was an incident on our last night in Folkestone which put me in mind of an earlier dissolution. Fred had been out carousing, and returned to his room half seas over with a hussy on his arm. Shortly afterwards we heard derisive female jeers. Fred is not in his first youth, and it seems that – how shall I put it? – his elderly member had failed to rise to the occasion. I remembered my days in the Trinity College library where I read a poem by Maximianus, the last Roman poet, who wrote in the sixth century as the western empire tottered to its end and the barbarians were already within the gates. He had enticed a pretty Greek girl into his bed, but found himself in the same unfortunate predicament. She burst into tears, and when he asked her why, she replied, ‘Nescis. / Non fleo privatum, sed generale chaos’ – ‘You do not understand. I weep not for your collapse, but for the collapse of everything.’

Copyright © Tachybaptus 2018

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file