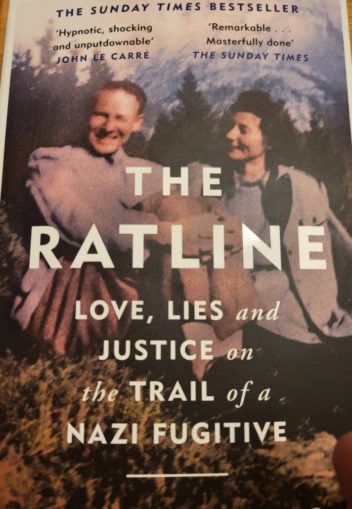

I don’t read non-fiction books that often, however I’m glad I picked The Ratline up when I was idly browsing suitable reading material for a holiday last year (the holiday got cancelled).

For, those (like me) who don’t know what a ‘Ratline’ was, here is a brief explanation (taken from Wikipedia):

“Ratlines (German: Rattenlinien) were a system of escape routes for Nazis and other fascists fleeing Europe in the aftermath of World War II. These escape routes mainly led toward havens in Latin America, particularly Argentina though also in Paraguay, Colombia, Brazil, Uruguay, Mexico, Chile, Peru, Guatemala, Ecuador and Bolivia, as well as the United States, Spain and Switzerland.

There were two primary routes: the first went from Germany to Spain, then Argentina; the second from Germany to Rome to Genoa, then South America. The two routes developed independently but eventually came together. The ratlines were supported by some controversial clergy of the Catholic Church, and later used by the United States Intelligence officers.”

The book is written by Philippe Sands, a Professor of Law at UCL and a practicing barrister at Matrix Chambers. He has been involved in many important international cases including Pinochet, Congo, Yugoslavia, Rwanda, Iraq, Guantanamo and the Rohingya. He also makes regular appearances on radio and television.

I am somewhat ashamed to declare my ignorance when it comes to knowledge of the period prior to, during and just after WWII. At school I was taught about prehistory, the Kings and Queens of England etc but nothing about WWI or II. This might have something to do with me dropping the subject at the age of 14. I regret this now, but at the time I just wasn’t interested in things that didn’t have any direct bearing on my life (how wrong I was). As a result, I was absolutely delighted that The Ratline proved to be such a great education for me. Whilst it focusses on a single member of the Nazi party and his immediate family and associates, the events of the period are explained in a way which gave me a much greater understanding of what was going on in Austria, Germany and the occupied countries which are dealt with in the book.

The central character is Otto Wächter, born in Vienna in 1901, an Austrian lawyer, Nazi politician and a high-ranking member of the SS, a paramilitary organisation of the Nazi Party.

During the occupation of Poland in World War II, he was the Governor of the district of Kraków in the General Government and then of the District of Galicia (now for the most part in Ukraine). Later, in 1944, he was appointed as head of the German Military Administration in the puppet state of the Republic of Salò in Italy. During the last two months of the war, he was responsible for the non-German forces at the Reich Security Main Office (RSHA) in Berlin.

In 1940 68,000 Jews were expelled from Kraków and in 1941 the Kraków Ghetto was created for the remaining 15,000 Jews by his decrees. On 28 September 1946 the Polish government requested the Military Governor of the United States Zone that Wächter be delivered to Poland for trial for “mass murder, shooting and executions. Under his command of District Galicia more than one hundred thousand Polish citizens lost their lives.”

He managed to evade the Allied authorities for 4 years. In 1949, Wächter was given refuge by pro-Nazi Austrian bishop Alois Hudal in the Vatican where he died the same year, aged 48, reportedly from kidney disease.

These are the basic facts. What brought the story to life, for me, was the way in which the author told the story through the lived experience of Otto’s wife, Charlotte and his son (extensively interview by Sands), Horst. Charlotte kept a daily dairy and retained most of the letters and correspondence sent to her by Otto. This provided the means to go into considerable detail as Otto is promoted and moved from one post to another, within the Nazi party and SS.

Sands does an excellent job of comparing what is written by Charlotte (and the letters to her from Otto) with established facts. It is very clear that that Charlotte and Otto were both in complete denial about the horrors being inflicted on thousands of people under the control of orders handed down by Otto.

Horst (Otto’s son) was interviewed extensively by Sands and they struck up a close relationship during the many times they met. Horst was (and still is) convinced his father was not responsible for the deaths of many Jews and other innocent victims. He continually finds excuses for Otto, even when faced with irrefutable evidence to the contrary. One of Horst’s reasons for agreeing to be interviewed (apart from to exonerate his father) was to establish exactly how his father came to die. There were allegations that Otto was poisoned whilst on the run in Italy. Some evidence came to light to support this claim, whilst other facts suggested he died after contracting Weil’s disease.

For me, it was one of those books that once I had started, I could barely put down. It taught me a great deal about the political and historical events of this period and has left me with an appetite to educate myself further.

Even for those who consider themselves to be knowledgeable about this period of history, I would highly recommend this book to them.

© text & images Reggie 2022