By Sandro Botticelli – National Gallery, London, Public Domain, Link

We are at the end of Advent, the Christian season that looks forward to Christ’s nativity. Today I am not going to tell you what you most probably already know about Advent, its significance and meaning, but I want us to take a step back to ask some other questions I haven’t heard often asked before:

- Why did God send Jesus into the world where He did?

- Why did God send Jesus into the world when he did?

- Why did God send Jesus into the world in the form he did, i.e. as the son of a humble carpenter rather than as a king or ruler as the Jewish priests and elders assumed He would?

Firstly, one might wonder why we should even ask these questions? My answer is simple: because sometimes we can become too familiar with the traditional stories about the birth of Jesus and His extraordinary life to think about them afresh and to really understand them, and because familiarity can breed apathy, if not contempt, and this can lead to ignorance. This is where the so-called Christian West is today.

Why did God send Jesus into the world where He did?

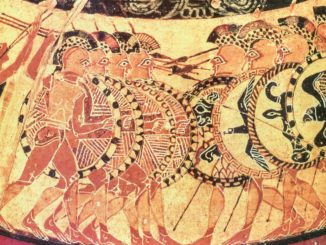

Now this map of the ancient world shows what we today call Israel and the Levant, which were all part of the Roman province of Syria and its sub provinces and client kingdoms such as that of Herod the Great. Remember those old maps like Hereford’s Mappa Mundi that show Jerusalem as the centre of the world? Well, in a way, they are true, at least in terms of the rise of world-changing civilisations. Israel is the land-bridge between Asia and Africa, and part of the sea-bridge between the trade routes between Europe, Asia and Africa, the Indian Ocean, the Mediterranean, Arabia, India and beyond, certainly before the Suez Canal was built which was with good reason called the ‘jugular of the British Empire’. It and Phoenicia to the north were nexus of the ancient world’s most important trade and military routes, fought over by every near Eastern and Mediterranean empire for many millennia. They all went through it – the Egyptians, Hittites, Sea Peoples, Babylonians, Assyrians, Persians, Greeks, Romans, Arabs etc.

In Jesus’ time, the Greek-Egyptian city of Alexandria along the coast on the Nile Delta was the intellectual capital of the Roman world, more so than Athens, but it was also the chief city of the Jewish Diaspora and the intellectual capital of the Jewish world, it’s where many early Jewish Christians fled and most probably where the three synoptic Gospels – Matthew, Mark and Luke – were written.

The Levant was full of ancient and wealthy trading cities, and, less well known to us, it was on the intersection of the two great international language groups of the day – Greek to the West and Aramaic to the East. Jesus spoke Aramaic, but many of the Disciples seem to have also spoken Greek, such that they all wrote in Greek as well as speaking Aramaic and Hebrew.

Furthermore, to the East was the Parthian Empire which was pressing up against the eastern frontier of the newly established Roman Empire, a place where many spoke Aramaic as well as Greek and their native languages. This is significant because many Jews had not returned to Israel after their exile was ended by Cyrus the Great in the middle of the 6th century BC, but had stayed behind in Babylonia and surrounding provinces as loyal subjects of the Persian Empire so there existed to the east of the Roman Empire a network of thriving Jewish communities throughout the Parthian Empire and even beyond, that is modern Iraq, Iran the Central Asian ‘stans etc. A final point about the Parthian Empire – it was Zoroastrian and immensely tolerant of other faiths, far, far more so that the Roman Empire – early Christians were quite safe there and some Apostles went east rather than west.

In summary, if you wanted to found a new faith to spread a new message around the ancient world quickly, the Levant/Israel is where you would start, at the centre of the trade routes, in a place where the two great international languages were spoken, and where the host culture had large expatriate communities dotted about the surrounding nations to act as receptors and transmitters for the new faith.

Why did God send Jesus into the world when He did?

We must start by considering the evidence as to when Jesus was born, something about which the Gospels give us a few clues. Firstly, they say Jesus was born at the time of an Imperial Census during the reign of Herod the Great, when Augustus was Emperor and in the time of the Syrian governorship of Quirinus. Herod died in 4 BC, a paranoid and mad butcher of his own family and everyone else near him, whereas the records say that Quirinus was not governor of Syria until 6 AD, so there was always thought to be a big problem with the historicity of the Gospel accounts – until a few years ago an archaeologist dug up a coin of a governor Quirinus of Syria dated to between 11 BC and 4 BC, so either there was an earlier unrecorded Syrian governorship of Quirinus or, more probably, this earlier one was a junior governor of a province of Syria. Either way, the problem has fallen away. Today, 4 BC, right at the end of Herod’s increasingly psychotic reign, is accepted as the most likely date for the birth of Christ.

The Roman historians Suetonius, Josephus and Tacitus all mention Jesus and that he was executed in the reign of Augustus successor Tiberius, who died in 33 AD.

So why now? It’s simple. Not until the Roman and Parthian empires bumped into one another had there ever been a stable international order stretching from the Atlantic to Pacific. The whole of the arc of civilisation was controlled by just four super-powers for the first time – Rome, Parthia, China and India, and orderly global trade and diplomatic relations were possible. There were conflicts, but they were not endemic, and for the first time a trader or missionary could travel peacefully from Spain to India or China, but this was a narrow window of peace and order that broke down within two hundred years, by which time there were growing Christian communities in India, China, the Middle East and Western Europe.

Why did God send Jesus into the world in the form he did, i.e. as the son of a humble carpenter rather than as a king or ruler as the Jewish priests and elders assumed He would?

As we have seen from my series on Isaiah, arguably the most important of the Hebrew prophets, his chapter 53 gave plenty of specific clues about the nature of the Messiah, even a physical description, and made it quite clear that Jesus would be humble born, common looking etc. And yet the Jewish clerical establishment missed it – they expected the Messiah of the Second Coming, a great military leader to drive out the Romans, but even this they saw as a purely Jewish enterprise whereas Isaiah was quite clear that the Messiah of the Second Coming would be a global affair, not narrowly Jewish. It just shows that one can’t trust clerics to interpret Scripture!

The Jewish elite of Jesus’ day were fixated on the Maccabees of 160 years earlier, who had launched a sort -of-successful guerrilla war against the Seleucid Greek kings of Syria, but Isaiah etc were quite explicit that the Messiah would not come in this guise. Consequently, they didn’t recognise Jesus for what he was, in fact they resented him for revealing their ignorance of Scripture. He warned them of the consequences of their folly, but they chose to ignore him and then murder him. The Jews then resorted to three increasingly calamitous revolts against the Romans. The first is the best known today, due to the destruction of Jerusalem and the Temple, and of course the siege of Masada, but the third under the Emperor Hadrian was the worst because it ended with the eradication of Judaea, a genocide costing over 580,000 Jewish live, the enslavement of hundreds of thousands more and the ethnic cleansing of the Jews from their homeland.

This third revolt was led by Simon Bar Kochbar, or ‘Son of the Star’, who was believed by his followers to be the ‘Messiah’. Once again the Jews had believed in the Messiah they wanted rather than the one they were promised by Isaiah.

Jesus came to us as the son of a humble tradesman in complete contrast the Jewish expectations for several reasons:

- His kingdom is not of this world- He does not conform to Earthly expectations.

- His law is one of moral and spiritual authority, not temporal power. It’s totally different from that of shariah or Islam.

- For Christ to come openly in power would destroy human Free Will. God loves us and gave us Free Will because He wants us to love freely, not from fear or compulsion. This is another contrast between Christianity and Islam, which means ‘submission’.

So Jesus came in the guise of a humble man, became an itinerant teacher, to deliver His massage while not subverting the Divine order.

Conclusion

So what can we draw from all of this. Firstly God chose his timing and location well – it was the first time in human history when a faith aimed at redeeming the whole of mankind could take off and spread readily, and especially in the land bridge and trading nexus of the ancient world.

Equally significantly, God kept his promise as to how He would come, as laid out in Isaiah, but the Jews preferred to believe in a god made in their own imaginations, rather than the one promised in their own scriptures, just another example of human delusion and folly, a cycle sadly repeated in every generation.

© 1642again 2018

Audio file

Audio Player