June 3rd, 1811.

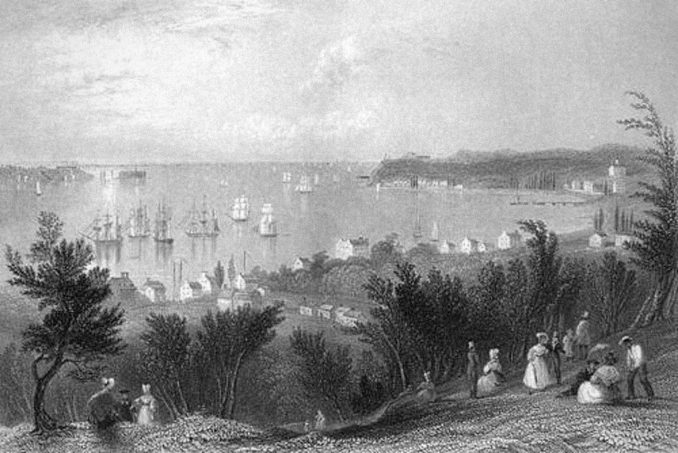

The city of New York lies in a broad river estuary whose wooded slopes give no hint of what will appear around the corner. The river is divided into several channels, forming the island of Manhattan on whose south end the city stands.

We anchored in the harbour and went ashore in the ship’s two boats, now cured of their leaks with a coating of Trinidad asphalt. The waterfront is adorned with handsome buildings that would grace any European city, and the quayside was bustling with every kind of activity, while a babel of most of the world’s languages met our ears.

After the Count had transacted the usual business with the harbourmaster, he told us that, despite his Russian name, his London accent had raised some hackles. More than thirty years after the colonies broke their ties with Britain, feelings are still running high. Indeed, in the present conflict Americans seem to be taking the side of the gimcrack tyranny of Napoleon, the very opposite of the ideals to which they claim to aspire.

Safe in our Russian nationality as long as we do not speak English, we repaired to a tavern and, while imbibing some lamentably bad whiskey apparently made from maize, listened to the local gossip. Two subjects were constantly mentioned.

First, the state of New York has recently abolished slavery, for which it is to be congratulated, but it has done so in a gradual way: the freed slaves have to serve a kind of apprenticeship, in which they remain indentured labourers paid a derisory wage, for some years before they become citizens. There are now many completely free Africans in the city, but I noticed that the only black faces were those of the tavern servants, and I surmise that it will be many years before they take a full part in the life of the district – if indeed they ever attain it. It is in the nature of any society to keep its lower ranks in their place but, if they are not provided with a ladder by which they can ascend, civil unrest invariably results.

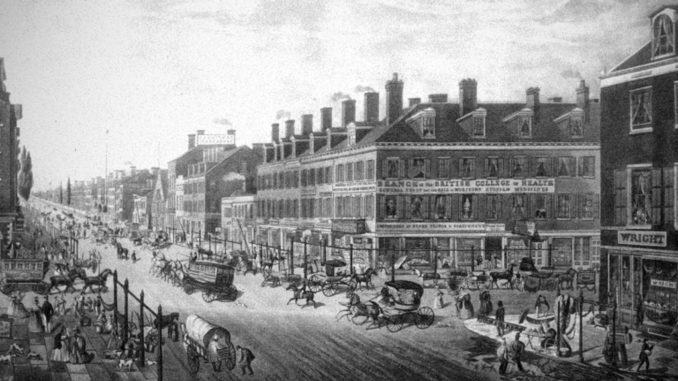

Second, the municipal leaders have grand ambitions for their city. They expect it to spread northwards over the entire island, and to this end they have divided its surface into rectangular plots which are now being marked with inscribed boundary stones. This plan has aroused the ire of the many farmers in the north of the island, who expect to be expropriated and driven off their land with little compensation. While their plight may inspire a certain sympathy, let us not forget that the original natives of the island were expelled by the first Dutch settlers when in 1626 they bought Manhattan island from them for 24 dollars’ worth of trinkets and beads and a jug of the execrable spirit we were drinking.

May I add that American beer is but a pale shadow of the real article. The inhabitants have also tried making wine from the fox grape which grows wild here, so named because of its odour, with unhappy results.

June 5th, 1811.

The city presents an animated spectacle, to such an extent that one must take great care when crossing the broad and crowded streets to avoid being felled by a furiously driven wagon. The principal languages that one hears spoken, apart from English, are Dutch and German.

When we had purchased all those items we required for our continued voyage, we resolved to explore the country to the north, beyond the present limits of the city. It is a pleasant landscape of rolling hills, forests, clear streams and small farms, and it will be sad to see it swallowed up by the dreary rectangles of the planned streets whose cornerstones are everywhere to be seen.

We fell into conversation with an aged farmer, a Mr de Kuiper, whom we met leaning on the front gate of his property. He was surprised to see bears, he said; they had been plentiful in his youth but the coming of Europeans had driven them out completely. This saddened us, as we had hoped to meet some of our American cousins. There were also very few of the original human inhabitants, expelled in the same way. While the European incursion into Manhattan, and into the east coast of America as a whole, may have begun as a colonial venture, it is now looking more like a complete replacement of the population by settlers of European stock, and of course their sad train of Africans brought in as slaves – and still such in reality, for all the boasts of emancipation.

It must be said that all civilisation depends on slave labour, or something like it. The prosperous lives of respectable citizens can be maintained only by hordes of miserable wretches toiling in the shadows, and paying these unfortunates a derisory wage does little to disguise their servile status. Even in famously free Britain we are sustained by labourers in the farms and mills working for a few shillings a week to supply our needs. Yet such is the way of all society, be it human or that of other animals: there must always be a hierarchy, and all worthy attempts to level it out end in failure.

On a more cheerful note, the joyous birth of Marina has had its consequences among the bears. My own dear Bruin has taken Angelina as his mate, and I am happy to say that she is already expecting a cub; and so is Peter’s mate Emily. It is early yet, and both cubs will probably be born on land after we have finally reached home. God willing, I shall be a grandmother!

Despite all the varied distractions and adventures of our voyage, we are all longing to stand on our native soil again, be it in England or Russia. In the words that Homer put into the mouth of wandering Odysseus,

Ἀλλὰ καὶ ὣς ἐθέλω καὶ ἐέλδομαι ἤματα πάντα

οἴκαδέ τ’ ἐλθέμεναι καὶ νόστιμον ἦμαρ ἰδέσθαι.

εἰ δ’ αὖ τις ῥαίῃσι θεῶν ἐνὶ οἴνοπι πόντῳ,

τλήσομαι ἐν στήθεσσιν ἔχων ταλαπενθέα θυμόν·

ἤδη γὰρ μάλα πολλὰ πάθον καὶ πολλὰ μόγησα

κύμασι καὶ πολέμῳ· μετὰ καὶ τόδε τοῖσι γενέσθω.

But every day I wish and yearn to reach

My home, and see the day of my return.

And if some god should smite me on the sea,

I will endure it, for my heart is strong.

Already I have suffered and toiled much

At sea and in the war; add this to that.

June 7th, 1811.

Last night Anton, one of the ordinary seamen, returned excitedly to the ship with the news that he had found a proper Russian tavern frequented by Russian sailors, with not a word of English spoken on the premises. We resolved to visit it this evening, and he led us to the east end of the city, accompanied by the entire crew except the unhappy ones whose turn it was to keep watch on the vessel, and even those we reduced to a minimum.

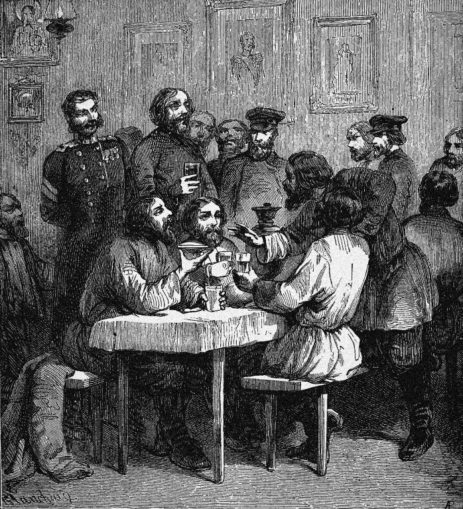

And there it was: a wooden sign bearing the legend Волжская Таверна, The Volga Tavern, in Russian – but not in English – led us down a flight of rickety stairs into a basement from which sounds of merriment emerged, mingled with the music of fiddles and balalaikas.

The entry of a nobleman in a fine suit trimmed with gold braid, two dozen bearded and rough-looking sailors, a young woman with flaming red hair carrying a small child, ten bears and a cub provoked no more than a moment of interest before the patrons returned to their pursuits. True Russians expect the unexpected.

We found tables in a corner and purchased several bottles of what we found to be very good vodka, a delightful discovery after the Americans’ unfortunate attempt at distilling spirits. Dolores and Beaivi, mindful of the welfare of their infants, preferred beer and even this, they said, far surpassed the pitiful brew sold elsewhere in the city. We sat at our ease and listened to the patrons as they boasted about their adventures at sea and their conquests of women (of whom the few present seemed to be available for ready money with little wooing required).

After a few minutes their natural curiosity asserted itself, and a few sailors drifted across to our tables and asked who we were and whence we hailed. The imposing figure of Count Bagarov, who alone among our motley band struck a fine figure, awed them a little, but when he told them that we had come to New York by the North-East Passage and the circumnavigation of Asia, there were politely raised eyebrows.

Fred (or I should say Fyodor) broke in with his now fluent but ungrammatical Russian, ‘We couldn’t’ve done it without the bears. Did you see how they manned the ship when we came into harbour?’

Some of them had seen our superbly drilled taking in and furling of the sails, and there were grudging nods. Seizing the moment, I took my slate and wrote on it, Кроме того, мы не обычные медведи. Мы можем танцевать так, чтобы удивить всех вас – Besides, we are no ordinary bears. We can dance so as to astonish you all.

That really did command their attention. The Count signalled for some tables to be pushed back. Jem took out his flute and Fred borrowed a violin from the bandleader. Then we launched into our well practised routine, choosing the quicker dances that would appeal to a tavern audience. When we came to the culminating gopak, the band joined in to the familiar melody while everyone else ecstatically clapped their hands. As the bears subsided gratefully back on to their benches, the applause and cheering were deafening.

We mingled with our hosts and toasted them in more vodka – it was no occasion for remaining sober. The foreign accents of Fred, Jem and Dolores excited polite comment, but when they told the story of how they Fred had been sentenced to hang in a corrupt trial, and how Jem and Dolores had snatched him from his fate, a wave of sympathy and understanding swept across the company. No doubt many of them have had their own troubles with the authorities. Now we were all Russian brothers and sisters for life.

I should mention at this point that Fred (or Fyodor) and Jem (or Yevgeny) are very different in appearance from the neat, nondescript Englishmen who set out for St Petersburg. Both are hirsute and tanned by wind and weather to the colour of mahogany; and Fred, with a flowing grey beard, looks like one of the Old Testament prophets in an Italian religious painting. Dressed in the last patched and ill fitting remnants of what the ship’s slop chest could furnish, they present a magnificently ruffianly appearance. Even were Fred to stroll past the Old Bailey in London, where the officers of the law are no doubt still eager to apprehend him, they would not have the slightest idea of his identity.

I am not entirely sure how we made our way back to the ship, but I remember a moment when the city watchmen appeared on the scene and seemed to be taking exception to our unsteady singing, roaring company as we lurched through the streets, only to fall back as a phalanx of bears surged to the front. I am a little surprised that I have still been able to write an account of the evening’s adventures, but now I shall subside gratefully into my bunk. Tomorrow we shall haul up the anchor and depart on the last leg of our homeward voyage.

Copyright © Tachybaptus 2019

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file

Audio Player